The Unmissables: Three Artworks to See in April

The best art on show in the dealer galleries of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in April 2021.

A monthly round-up of artworks from the dealer galleries of Tāmaki Makaurau that we keep returning to.

In this month's Unmissables we travel across time and dimension. From a plastic flower portal, we emerge to the totemic status of the cat in a civilisation long past. Then we revisit a somewhat sadistic nursery rhyme and remember that art that allows the observer to time travel... is magical.

Our team of art critics, Ngahuia Harrison, Francis McWhannell and Tulia Thompson, have trawled the streets of Auckland and online to showcase some of the most exciting art around.

I chat to Martin Basher alongside his large scale, compelling paintings at Starkwhite on a too-hot April afternoon (climate-telling heat!) He wonders out loud whether his paintings will read differently here than in the New York winter – he’s left his home of twenty years, New York, to escape Covid-19. The orange-beaked bird of paradise flower, which features in many of his paintings, is so strange and ‘alien’ and yet fairly common in our backyards. Actually, they remind me of the dark brown teacups with red and orange bird of paradise flowers made by Crown Lynn in the 1980s.

Bird of Paradise shows the abstract, gradient works Basher is renowned for, sparking against layered works that visually connote still-lifes while combining abstract and hyper-real elements. In some, the finely painted, realist flower is doubled in flat, orange segments. Basher says life in New York during Covid-19 caused an “exploding of a lot of the previous composition”. What opened up for him was ‘formal play’. The paintings achieve the beauty and silence of still-lifes - like careful ikebana arrangements - and hint darkly at our social and environmental conditions under neoliberal capitalism.

Basher has long been interested in commodification and the environment. The carefully rendered bird of paradise is painted from a plastic model instead of the living plant. Under the White Sky: The Nature of the Future by Elizabeth Kolbert (a book Basher refers to) describes how we humans have repeatedly tried to ‘fix’ our environmental disasters with even greater human-fuelled damage. Plastic Birds of Paradise, then, a wry smile at the egoistic Anthropocene. But still, how to account for their rare beauty?

There are black and white hyper-realist seascapes embedded into the ikebana arrangement within the untitled work. Surface ripples swell from a small, bush-covered island. Stars in the night sky. The black silhouette of a palm tree. It hits you in fragments, the way memory bursts open and reorients you. A purple circle rises, floating between dimensions. Orange, plastic flowers might be a portal. - TT

Martin Basher

Starkwhite

13 April – 14 May 2021

Martin Basher, Untitled, 2021

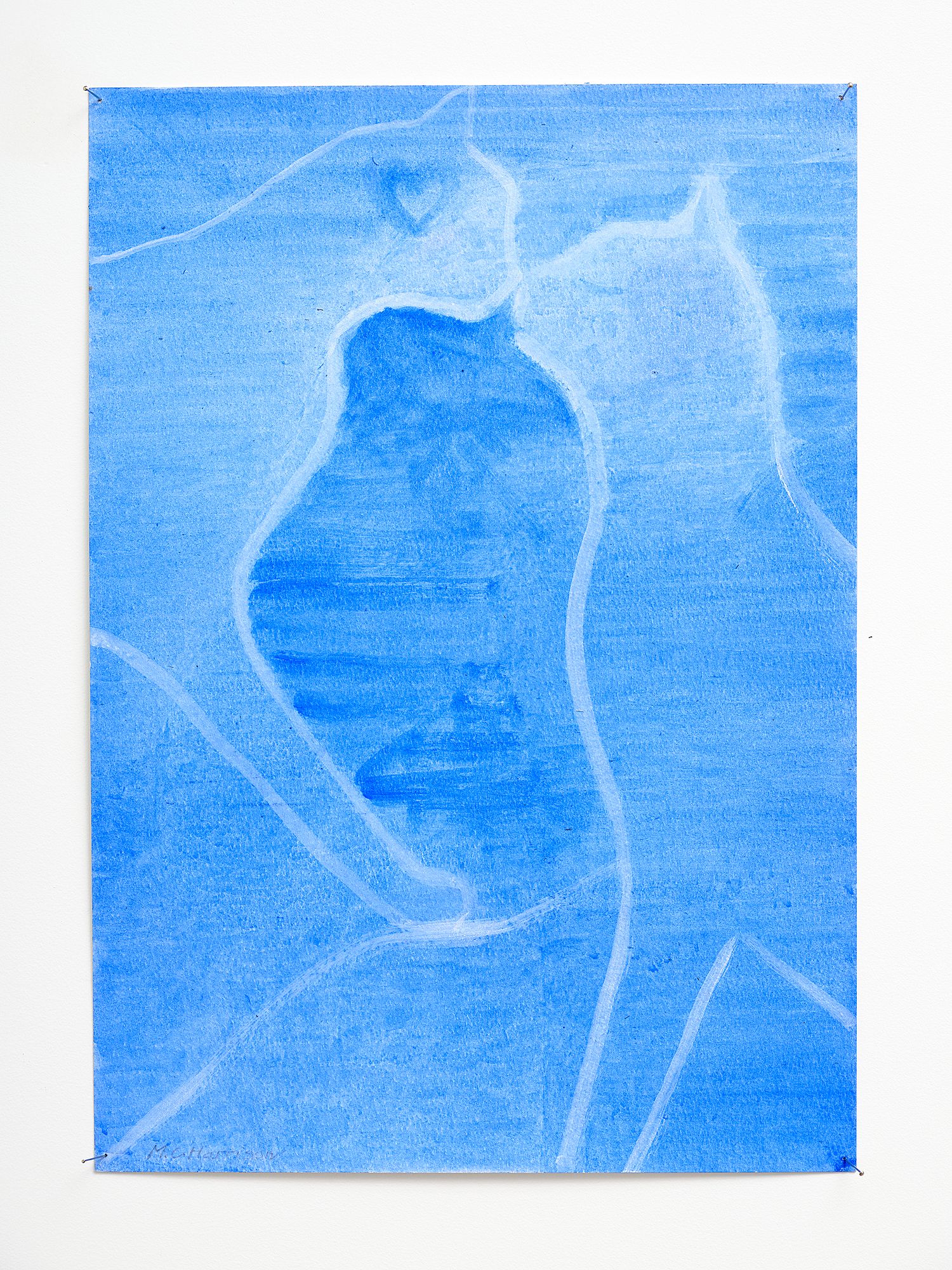

Visiting Michael Harrison’s new show, The Freedom That Awaits Us, I experience something akin to déjà vu. I feel that I already know the pictures. This is not a criticism. While shifts in style have occurred over the thirty-odd years of Harrison's career (I spy more gestural marks in his paintings these days), his oeuvre is remarkably unified. Works by an artist often feel like the pages of a book, coalescing into distinct chapter-shows that support a broadly linear narrative. Harrison’s operate differently. Typically executed on compact sheets of paper, his paintings are like cards in a deck. They are marked by recurrent motifs and are more than happy to be shuffled. Those in The Freedom That Awaits Us resonate as strongly with older works by the artist as with one another.

In fact, the notion of age can be complex where Harrison’s pictures are concerned. Many are made over considerable spans of time. Even after being exhibited, a work might be reabsorbed into the studio and further tinkered with. Mutability, from the present show, was begun in 2000 and only paused this year. Monumental as his paintings go, it depicts a pair of cats touching noses and displays his signature treatment: acrylic paint applied in delicate washes that evoke watercolour, flattened forms that suggest silhouettes, and a restrained palette (here, ultramarine predominates). The picture, like many by the artist,creates the impression of a dream, half-remembered, or perhaps a premonition, half-perceived.

Harrison has long painted cats. They hold a kind of totemic status in his practice (looking at his works, I am often reminded of the Egyptian cat goddess, Bastet). In Mutability, they seem to act as figures for human relationships, particularly romantic ones. A love heart hovers inside the head of the left-hand being. Cats are deeply familiar. In the age of internet videos, they are almost too familiar. In Harrison’s hands, however, they constantly beguile. The artist has an uncanny knack for teasing the timeless out of the everyday. His pictures tap into our desire to tether private longings and apprehensions to entities outside ourselves. They listen to our concerns, both momentary and persistent, and speak with the delicate imprecision of the most potent auguries. - FM

Michael Harrison

Ivan Anthony

10 April – 4 May 2021

Michael Harrison, Mutability, 2000-2020

For a few years, I have passed 90 Anzac Ave lamenting the building wasn’t a gallery. It could’ve been the latest tech start-up in an over-inflated property market - but my wish has materialised. 90 Anzac Ave now boasts Sarah Hopkinson’s newest project, Coastal Signs. And the maiden show is Pumice by Ammon Ngakuru.

Pumice is that light-but-scratchy stone your Nan might use on her calluses. In Ngakuru’s exhibit, the painting of the same name Pumice shows a house-boot, reminiscent of the one the old woman lived in. The exhibition toys with underhanded violence similar to the light-but-brutal sadism of nursery rhymes; the old women did ‘whip them all soundly’ after all. The sculpture, Silver (my slow response), uses the conventions of museum display, specifically a plinth, for a decommissioned sword and a small egg-shaped rock. Real Food houses three cabbage butterfly corpses leaching on a Himalayan salt lamp housed in a Blundstone boot box.

The sculptures are surrounded by a suite of paintings that complicate an easy quest for meaning. A row of six small paintings and a diptych seem to organise a narrative that Ngakuru simultaneously destroys. The form of bunk beds looms large over these works, in the painting Primary, as a figure of sleep or nightmare. The salt lamp becomes a night light amongst the starry portrait, Pisces, the eerie cave in the painting Mill, and the closed Aviary (gate).

Ngakuru raises questions about the manner with which we proclaim to imbue artefacts with history and politics. If the sword is a signifier of British Imperialism, defunct as it may be, what do we know about the analogous harm? Or what about the salt lamp? Are we worried that it’s not kosher? Ngakuru has engaged conventions of a certain art-school narcissism, but it would be foolish to dismiss this careful obfuscation as navel-gazing. Perhaps the dead skin to be rubbed off is our meme-ing for meaning, the desire for identities in brackets so that our dream of the world is much less disturbed. - NH

Ammon Ngakuru

16 April – 15 May 2021

Coastal Signs

Ammon Ngakuru, Pumice, 2021

.

The Unmissables is presented in a partnership with the New Zealand Contemporary Art Trust, which covers the cost of paying our writers. We retain all editorial control.

Feature image: Ammon Ngakuru, Pumice, 2021. Image credit: Alex North.