From the Archives: The Thing About Culture Vultures

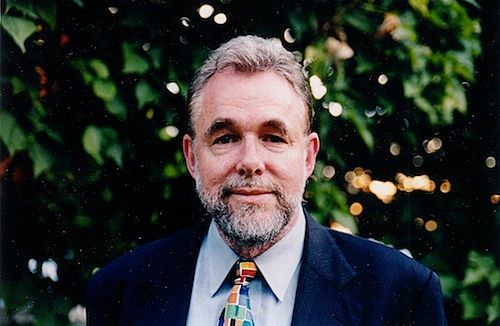

Roger Horrocks on 'difficult' contemporary art, its critics, and the shadows of anti-intellectualism

Roger Horrocks on ‘difficult’ contemporary art, its critics, and the shadows of anti-intellectualism.

The following is an excerpt from Horrocks’ essay, ‘A Short History of “The New Zealand Intellectual”’, which first appeared in Speaking Truth to Power (2007), edited by Laurence Simmons. It also features in his new book, Re-Inventing New Zealand: Essays on the Arts and the Media, which launches today at the Gus Fisher Gallery, University of Auckland.*

The thing about culture vultures

Although a tradition of experimental writing and associated theory has maintained a lively but marginal presence with the help of ‘little magazines’, the only art form in New Zealand that has consistently given prominence to experimental work is the visual arts. Not surprisingly this area has been the site of much public debate, richly documented by Jim and Mary Barr in their book When Art Hits the Headlines: A Survey of Controversial Art in New Zealand.The hard-line common sense attitude is that difficult art is a kind of confidence trick, and art experts are intellectual bullies who try to intimidate those who can see through the racket. Since common sense also assumes that art should at least be serious, it is baffled today by the many works that have a playful or ironic tone, interpreting them as further proof that artists are sneering at the public. Older art experts whose taste has been shaped by earnest forms of nationalist art also tend to have difficulty with post-modern playfulness.

The hard-line common sense attitude is that difficult art is a kind of confidence trick, and art experts are intellectual bullies who try to intimidate those who can see through the racket.

Just as artists are hesitant to describe themselves as intellectuals, their critics would never see themselves as anti-intellectuals – rather, they are bravely speaking out against snobs and bullies. A prominent example is Michael Laws who has frequently attacked ‘pseudo-elite’ art and the intellectuals who defend it. On 3 October 2004 he wrote a Sunday Star-Times column on ‘professional dunces,’ New Zealand’s know-it-alls: ‘Most of history’s great crimes have been perpetrated by those who assumed that they’d been gifted an especial knowledge. And books are no better. The Hitler Youth was probably onto something when it decided to chuck onto the bonfire as much of the West’s great literature as they could find…. Too bad they stopped before they got to D.H. Lawrence.’ He added an attack on today’s education experts: ‘The great irony is that Kiwi society worked best when fewer had degrees and more had jobs. Yes, but these are post-modern times and that means that fad is the fashion and that trend is the trade. We suddenly have a gross over-supply of fashion designers, media studies graduates and arts effetes.’

Laws’s typically jokey manner allows him to get away with comments like the one about Hitler Youth as we assume he is just being playful and provocative; but since becoming Mayor of Wanganui in October 2004, Laws has shown that he means business. Claiming that he was championing the ratepayers of Wanganui against those he called the ‘culture vultures,’ he immediately went to war with the local public art gallery (the Sarjeant) and scotched plans for an extension. As the Sunday Star-Times reported, ‘Law’s assessment of the gallery’s contents is blunt (“it’s crap!”)’. The Gallery’s trust board members ‘all resigned after they were dressed down several times by Mr. Laws’. The Mayor is now planning to sell some of the paintings in the gallery collection. He defended his approach in his Sunday Star-Times column of 28 December 2004 as a ‘collision between elitism and reality’. Laws represented common sense whereas the arts community consisted of pretentious intellectuals in alliance with idle wealth. In his words: ‘there is one group that hovers above all in the hoity-toity stakes that regards the rest of humanity as little more than shaved monkeys – as uncivilised, unwashed plebians with neither taste nor refinement. I refer to the arts fraternity.’ Artists and ‘their hangers-on’ are always ‘bleating’ for more public money.

Laws broadened his attack from the visual arts to highbrow art in general, to other forms of elitist nonsense such as ‘that loathsome caterwauling known as opera.’ He went on to claim, with startling inaccuracy, that no public funding was available for popular music. As for classical music fans: ‘Why these bludgers can’t support their own musical tastes is utterly beyond me. Indeed, how ironic that the poor of Otara pay for their tastes while the rich of Remmers soak the taxpayers for theirs. But that’s the thing about culture vultures. They automatically assume that their tastes are worthy – that because they have chosen something so spectacularly inaccessible, then it’s up to others to pay.’

One is reminded of Pearson’s comment back in 1952: ‘It is common for some people to accuse people who go to symphonic concerts of not understanding the music and going out of snobbery’. For Laws, to encounter art that is difficult immediately triggers the traditional assumptions that it is bogus, elitist, made for the rich, and a con game by which bludgers seek to rip off the public. His polemics vividly confirm Pearson’s insight that ‘being different’ in New Zealand is interpreted as ‘trying to be superior.’

For Laws, to encounter art that is difficult immediately triggers the traditional assumptions that it is bogus, elitist, made for the rich, and a con game by which bludgers seek to rip off the public.

The Laughing Donkey

One of the most dramatic recent art controversies began in July 2004 when the artist et al was selected for the following year’s Venice Biennale. In art circles the choice of artist was hardly a surprise as et al had been active for over 20 years and had recently had an outstanding retrospective at the Govett-Brewster. But et al was little known outside the art world. Critics pounced on the fact that public money was involved and that the artist was described as representing New Zealand. Creative NZ made $500,000 available towards expenses, with the rest of the budget to be raised from sponsors and the public. The media assumed that the artist was receiving a huge windfall, whereas in fact the Creative NZ money was to help with the overheads – the rent of a venue in Venice for six months, project management, the opening of the show, publicity, airfares, the production of a catalogue, etc. As John Daly-Peoples later pointed out, et al had received no direct grants from Creative NZ in recent years, and only about $25,000 from public galleries over the last decade. (Merylyn Tweedie, the coordinator of et al, had needed to hold a ‘day job’ as high school teacher.)

There was outrage at the fact that the collective (or was it the single artist Tweedie?) avoided publicity except under controlled conditions. In today’s commercial culture it is seen as only proper that an artist should work for her supposedly huge salary by doing PR for her country. But above all what the debate focused on was et al’s type of art - ‘conceptual art,’ or what a Dominion Post letter-writer described as ‘self-indulgent pseudo-intellectual claptrap.’ The artist had worked in a variety of media but was best known for installations using recycled junk. The most recent example – and the only example et al’s critics appeared to have heard of - was ‘Rapture’ at the Wellington City Art Gallery, a closed box reminiscent of a New Zealand ‘dunny’ or ‘portaloo,’ which emitted sounds said to be recorded at the French underground nuclear tests at Mururoa. Other sounds were reminiscent of a braying donkey. This work was confused by the media with another work on exhibition at that time as part of the contribution by three New Zealand artists to the 2004 Sydney Biennale. Daniel Malone’s ‘A Long Drop to Nationhood’ made witty use of the awkward corridor space the artist had been allocated by placing a ‘long drop’ at the end. The public condemnation of these two works curiously echoed one of the very first modern art controversies, about the exhibition of a urinal in a New York gallery in 1917 by Marcel Duchamp operating under the pseudonym ‘R. Mutt.’

The Dominion Post fuelled public protest by its front page lead story on 14 July 2004 with the headline ‘Portaloo to Promote NZ: Cash Down The Toilet, Say Critics’. In fact the portaloo was never intended to be et al’s art for Venice, but the Post was not interested in such subtleties. The story quoted Act MP Deborah Coddington: ‘It’s crap – and most New Zealanders know it.’ (‘Crap’ is the automatic association for strange art, and the word would be heard constantly over the next few weeks, though few users of the term seem to have reflected on its irony in this instance.) The Dominion Post caught Associate Arts Minister Judith Tizard unprepared and very much on the defensive: ‘Tizard is demanding answers…. “I think that Creative NZ have to answer the charge that this is arrogant and elitist,” Ms Tizard said last night.’ She had not yet seen the work in question. Two weeks later, Tizard - who is normally a strong supporter of the arts – was able to assure critics in Parliament that Creative NZ did have satisfactory answers. But meanwhile the Dominion Post story created fallout on a Mururoa scale.

That evening, the country’s best-known current affairs commentator, Paul Holmes, devoted much of his TV One show to the topic. In a voice dripping with irony, he informed his audience that ‘We the taxpayers are to pay around half a million dollars to send to a very elegant international art exhibition an unseen work by an artist whose latest work is a dunny that brays like a donkey.’ He then gleefully quoted various ‘experts’ who had praised et al’s work, adopting an affected posh voice as he read their comments aloud. His aside to the audience was: ‘Please feel free to throw up!’ Other provocative details were supplied by a sarcastic associate who added the rhetorical question, ‘Do we simply not understand art like this?!’

There will always be a dealer or critic who sees the artist under attack as over-rated.

Art dealer John Gow and art consultant Hamish Keith appeared as experts who had decided it was advantageous on this occasion to side with the populists. One of the problems in such controversies is that the art world seldom presents a united front. There will always be a dealer or critic who sees the artist under attack as over-rated. Typically they will justify their alliance with populism on the basis that controversy is healthy because (as Gow remarked to Holmes) it is encouraging to see New Zealanders talking about art. The two experts adopted a nationalist stance, with Gow objecting that et al’s site-specific installation (whatever it might turn out to be) was unlikely to make the Italians think of New Zealand. Better to have selected ‘a paua shell work by Ralph Hotere and Bill Culbert’. Gow must have known that et al’s work has been deeply involved with representing ‘New Zealand’ (albeit from an ironic perspective), but here he was playing to Holmes’s common sense assumption that any art that represented the nation overseas had a duty to make it look good. As for Keith, he followed up his Holmes appearance with a letter to the Editor of the Herald on 17 July: ‘New Zealand art is alive, flourishing and connected to its culture. A great pity that Creative New Zealand and its experts do not seem to have noticed. We surely deserve more than this flatulent donkey in a dunny.’ These remarks implied that nationalist art had achieved its goal of becoming fully ‘connected to its culture,’ but clearly it had done so at a cost – the loss of the critical distance that separated art from populism. (It has become difficult to explain to young people in the arts who know only today’s establishment or coffee-table versions of nationalism that once it was a critically-minded counter-culture.)

In repeating the sound of a braying donkey on his show, Holmes seemed totally unaware that he was confirming the identification with himself. Few commentators noticed that Holmes had scored an ‘own goal’ – most appeared to believe that he and the Dominion Post had performed a valuable service to the nation in exposing another art world absurdity. Radio talkback and Letters to the Editor columns ran hot. Michael Laws used his next Sunday Star-Times column to enlarge the attack: ‘It’s time that the elitist rubbish that parades itself as installation art was exposed as the nonsense that it is…. Art should aim to uplift all, not just be for the few [etc.]'. Many politicians joined the outcry. Georgina te Heuheu, Arts and Culture spokeswoman of the National Party, was not afraid to flaunt her lack of knowledge of the artist’s previous work by asserting in a press statement that ‘Taxpayers have every right to be asking why Creative New Zealand has selected an installation by a group of artists whose claim to fame to date is the creation of a port-a-loo toilet which brays like a donkey….’ Stephen Franks of ACT deplored the way the so-called ‘experts’ of Creative NZ ‘spend the taxes of ordinary people on these artists.’ He added: ‘It is very easy for people in the arts world to despise and reject any notion that the hoi polloi, those of us who are not the insiders, should have a view on what the government should pay for by way of art.’ Today, ‘hard-earned money’ is being given to ‘tripe’ and taken away from ‘taxpayers who actually do try to beautify New Zealand and the world; taxpayers who build gardens, who buy things that they like, who buy CDs, and who pay to sponsor the music they prefer.’ During two periods of parliamentary debate he was backed up by other ACT politicians such as Deborah Coddington, Heather Roy and Ken Shirley. The NZ First attack was led by Brian Donnelley and Deputy Leader Peter Brown.

What else should be required of a sophisticated artist at the Venice Biennale? According to everyone from the Prime Minister, to Creative NZ, to the presenter of the TV arts programme Frontseat, to the editor of the Herald, New Zealand artists are apparently to be judged on their ability to undertake ‘ambassadorial and publicity responsibilities.’

All the main newspaper columnists joined in the witchhunt, including Jim Hopkins and Gordon McLaughlin in the Herald. The Dominion Post published a deluge of letters abusing the artist (‘public scam,’ ‘gibberish,’ ‘crap,’ ‘Emperor’s New Clothes,’ etc.). The most unlikely people became involved, including Kim Hill, who was known as Radio NZ’s most intellectual interviewer. As MC for the Montana NZ Book Awards on 26 July, Hill could not resist making et al jokes, such as introducing Peter Biggs of Creative NZ as ‘Peter Boggs’. Even the Prime Minister distanced herself sharply from the choice of et al by means of a technicality. Helen Clark is normally a strong supporter of the arts but she was obviously conscious of the strength of the public backlash. In Parliament she said it was not her role to comment on ‘the quality of the artist’s work’ but she was concerned that the artist would not be able to meet one of the criteria, ‘the ambassadorial and publicity responsibilities required in a major international exhibition project’. She added a warning: ‘I think this is a salutary lesson for Creative NZ, that if it delegates to a selection committee, the least it can do is ensure that it follows its own criteria. I can assure [Parliament] that that will have a bearing on my thinking about resourcing levels for Creative NZ in the future.’ In fact, et al has given many interviews within an art context in a lateral or playful manner, in keeping with the style of the work. What else should be required of a sophisticated artist at the Venice Biennale? According to everyone from the Prime Minister, to Creative NZ, to the presenter of the TV arts programme Frontseat, to the editor of the Herald, New Zealand artists are apparently to be judged on their ability to undertake ‘ambassadorial and publicity responsibilities.’

There were more sympathetic voices, such as Rosemary McLeod in the Dominion Post, John Daly-Peoples in National Business Review and Linda Herrick in the Herald. Creative NZ deserves credit for having held firm, though gossip suggests that behind the scenes the organisation was somewhat rattled. In ‘The Best Art of 2004’ in the NZ Listener William McAloon made the interesting suggestion that the et al controversy paralleled ‘the 1978 controversy surrounding New Zealand’s gift of Colin McCahon’s Victory Over Death 2 to Australia.’ If so, it was evidence that public attitudes had changed little over the past 28 years. The controversy seemed also a clear demonstration of how fragile much of the arts establishment still is, for almost everyone rushed to prove that they endorsed the moral (or anti-intellectual) panic.

The controversy seemed also a clear demonstration of how fragile much of the arts establishment still is, for almost everyone rushed to prove that they endorsed the moral (or anti-intellectual) panic.

Et al had the last laugh, for in October 2004 she won the $50,000 Walters Prize as judged by New York curator Robert Storr, a former senior curator of the Museum of Modern Art who will be the Director of the next (2007) Venice Biennale. Et al’s work Restricted Access was (as described by the Herald) a ‘grimly lit collection of exhausted technology.’ There was no portaloo with a braying donkey but there was a television set screening a clip of Holmes attacking et al. As for the 2005 Venice Biennale, et al created a new installation, described by international reviewers as ‘brilliant’ and ‘fresh.’ Storr confirmed that this work was ‘entirely suited to the Biennale.’ To date, none of et al’s New Zealand adversaries appear to have had second thoughts.