Who’s Afraid of Experimental Dance?

Victoria Wynne-Jones attends Experimental Dance Week at the Basement Theatre

Victoria Wynne-Jones attends Experimental Dance Week at the Basement Theatre.

The following actions are important to allow for full immersion into the audience experience which you are about to encounter.

Each action represents an empathetic response that is common while watching contemporary dance.

It is important that we release these urges before we enter the theatre, so as not to disturb the performers...

So intones artist Christina Houghton within her installation Healing safely: taking care, a series of instructions designed to prepare those who are about to experience experimental dance. In the instructional video Preparation 1. Pre-show briefing, set up in the foyer of the Basement Theatre, Houghton sits within an orange-coloured environment in a high-vis vest. In her best flight attendant voice, she guides prospective audience members:

You may find it difficult to keep your facial expressions to a neutral position.

You may experience surprise, laughter or confusion…boredom may also be a factor.

Particularly in experimental dance, you may encounter a horizontal position as opposed to a vertical position.

There may be a large quantity of stillness or periods of the performance where there is actually no music or it does not appear to be dance.

Houghton’s work is firmly tongue-in-cheek, yet it also acknowledges a very real fear – or at least, robust scepticism – about the very concept of experimental dance. Healing safely: taking care was presented as part of Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa NZ, a series of events that occurred across venues in Central Auckland in early February of this year. Organised by Alexa Wilson, a New Zealander currently based in Berlin, the festival was a celebration of works and practices that challenge received notions about what dance should be. In Aotearoa, experimental dance is inflected by a counter-colonial impetus, one that challenges a teleological story about dance developing from the Western European form of ballet, to formal and modernist experiments conducted in the US, post-modern movements, and back to Europe again with contemporary dance created by choreographers in large city centres like Berlin and Brussels. According to this narrative, practices that take place outside of this trajectory are designated as ‘other,’ ‘folk,’ ‘global’ and peripheral. Although the majority of the artists involved in this festival hold such stories within their bodies as part of their training in Western dance, each of their performances produced specific and nuanced dance experiments with the aid of bodies and voices, whether live or recorded. As explained by Wilson in a recent interview, even though ‘experimental dance’ may evoke fear or discomfort, she envisages the term ‘experimental’ to mean work that ‘reflects what is contemporary.’ Wilson states:

This work is often subtle, or clever, perhaps quite genuine and brave in its expression – finding ways to do and say things that are not mainstream. This can be daunting or challenging for some people. Someone feeling uncomfortable, questioned or challenged, is a probably a trademark of experimental work. Simultaneously one can feel invigorated, excited, activated, moved and inspired by it. It reflects what is contemporary.

*

The opening weekend, with its Wānanga Kanikani X organised by Rachel Ruckstuhl-Mann, foregrounded a broad range of activities, rather than just theatre-based performances. The wānanga brought together the experimental dance community for a series of workshops and exchanges on improvisation, parenting and storytelling in the context of its core principles of manaakitanga, whakawhanaungatanga and kaitiakitanga. While large pots of dal bubbled on the kitchen stove, small hands grabbed blueberries and carefully drew on large sheets of paper, dancers chatted and stretched on the floor or smoked cigarettes on the front porch in the sun. It is no coincidence that the event was held at the Old Folks Association Hall (OFA) on Gundry Street, for this modest, accessible venue and rehearsal space plays a crucial role in the experimental dance community. The weekend ended with a panel discussion facilitated by technician, choreographer and OFA facilitator Sean Curham on “Art and Money.” Indeed, one of the outcomes of the discussion was an acknowledgement of just how important spaces like the OFA are for experimental practitioners trying to make work in a city like Tāmaki Makaurau, with its cripplingly high living costs.

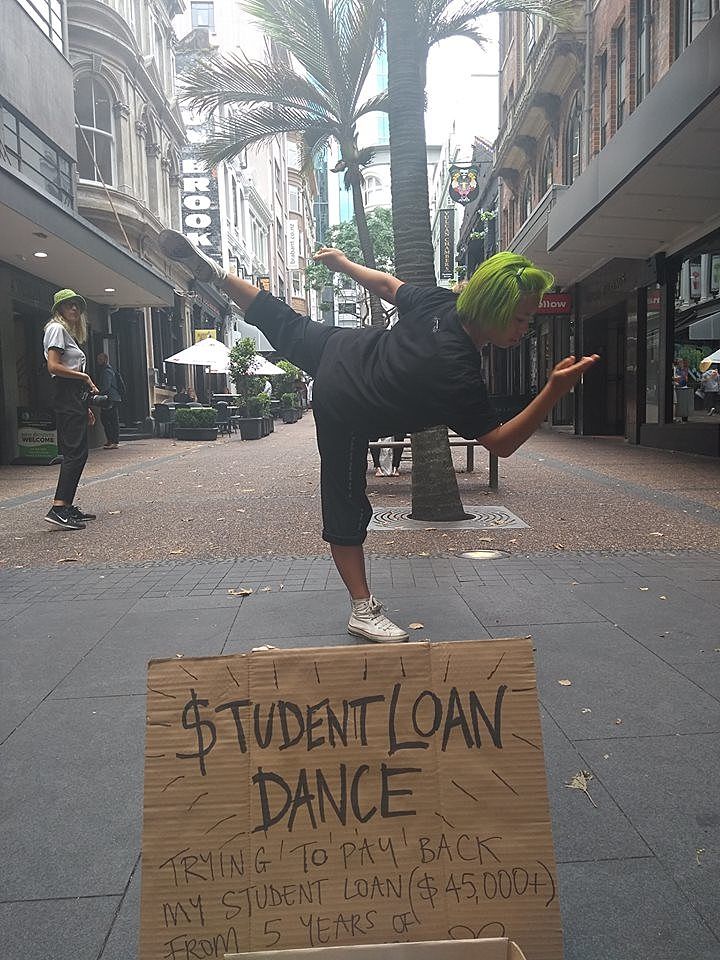

Off-site events flourished during the week, with many works involving the participation of audience members, as well as that of passers-by. For her Student Loan Dance, Alana Yee busked in the streets surrounding the Basement Theatre. Not having the financial means to pay for a studio whilst in town, Yee spent approximately an hour and a half each day continuing her daily training regime in public, moving in an improvised way, essentially dancing in the street. Tying into Curham’s fiscal concerns, Yee expressed a wish to explore her personal indebtedness. Acknowledging that she will probably never pay off a student loan accrued in the process of training to be a dancer by working as a dancer, Yee gratefully accepted donations that would go towards paying off her debt. The artist observed that the only people who gave her money were fellow buskers and those sleeping rough. Coinciding with Auckland Pride as well as the build-up to Fringe and Auckland Arts Festival meant that Experimental Dance Week enjoyed a thoroughly carnivalesque atmosphere. Like Yee’s, Mark Harvey’s work Help! meandered around the surrounding areas of Greys Avenue and the Aotea Centre. Armed with a hat and a communal bottle of sunscreen Harvey explored the possibilities of what he calls “consensus-based choreographic strategies.” With consensus, Harvey gently guided participants to provide various services, beginning with physical offers such as sheltering one person from the sun with everyone’s bodies and hands or forming a protective circle within which one person could walk around. Participants offered help to members of the public. The friendly security guards at a nearby television shoot declined the offer, as did most people. However, by consensus the group managed to form a human entranceway to an event in Aotea Square and collectively visit an open home in a nearby apartment complex. Two participants carried out a conversation, flopped down on the expansive bed holding hands, while others tried to see whether they could fill their water bottles in the newly minted kitchen or sat cross-legged on a plush black rug digitally printed with effusive flowers. Harvey’s Help! realised the trope of an artist together with participants providing a kind of service that importantly came without a price tag. Together with Curham and Yee, Harvey seemed to respond to a recent entreaty from political theorist David Hall for artists to explore “the economic infrastructure that their practices and livelihoods rely upon.”[i]

Over the next hour we witnessed the scientists re-enact continental drift via interpretive dance and we dipped our hands first in water then in salt crystals before letting them dry in the sun

The performances that occurred outside of the black box theatre required various degrees of participation from audience members but were also noticeable for their inclusive attitudes towards objects. No longer content for them to function as mere props, many of the artists sought to probe the complexity of relations between human bodies and other entities, objects, things and stuff. A container parked just outside the Basement functioned as a “shed of poetic encounter” housing Alys Longley’s Mistranslation Laboratory.[ii] At select times each day one could visit and be guided by friendly ‘scientists’ through a pick-a-path style adventure or mini-performance. When I attended, two performers in white lab coats guided our small group through a devised “buffet of experiments” that recognised the inseparability of human and non-human bodies. From a menu offering three courses – Emotional Experience, Atmospheric Field Trip and Workshop – the group chose (again by consensus) Fungi Drift, Salt Harbour Tuning and Change Failure Support Group. Over the next hour we witnessed the scientists re-enact continental drift via interpretive dance and we dipped our hands first in water then in salt crystals before letting them dry in the sun.

So we are noticing processes of continental drift, where bony land-forms drift in response to gravity, weight, light and time. Pressure on a specific structural element will impact on the entire system. Enabling the life of continents are oceans and waterways. Tides of cerebrospinal fluid flow up and down the spinal column, the same saline content as the sea. These fluids are to the trees of the nerves what rain is to the rainforests, allowing the transmission of response, emotion and idea, along branches pulsing and signalling, an ancient internet of the body.The branches of nerves are infinitely delicate, washing possibility through the forests of the body – fluids with the same saline content as the sea.

Throughout Mistranslation Laboratory I was reminded of the complex entanglements of bodies, worlds, substances, atmospheres and ecologies. “Durational Spritz” served as a palate cleanser in which the entire group sprayed misted water at an industrial fan so that we were in turn thoroughly refreshed.We collectively created a magical bubbling paste made from small notes we had made on what we would like to change about the world whilst the scientists cheered us on, singing David Bowie’s “Changes” and waving a “Change Failure Support Group” banner. Towards the end of the encounter demonstrations were given on how to leave the container according to whether one identified as an introvert or extrovert. Introverts departed slowly and decorously, whilst extroverts leapt from the container energetically, bellowing “Sweet Biscuit!”

I couldn’t help but wince at the sight of Archer mangling the lower half of a female mannequin with hedge clippers and smashing china plates and a small figurine of a ballerina with a hammer

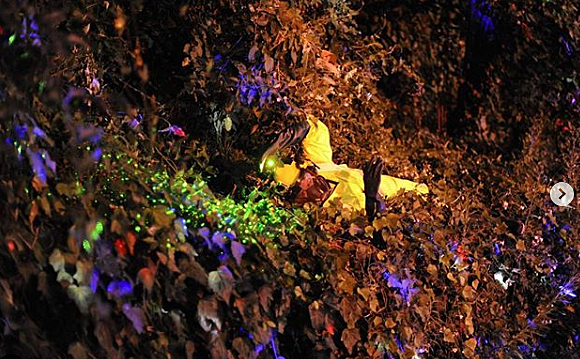

An entirely different orientation to objects was presented in Josie Archer’s interactive solo Search and Destroy, held late one night at the Audio Foundation. Audience members were asked to choose an object and a tool, then Archer would tell a story before destroying the chosen object with the chosen tool. Equipped with ear plugs and safety goggles, we bore witness to narratives that alternated between confessional, devastating and funny so that the deliberate blows she inflicted on each object could be read as cathartic, mournful and ridiculous. I couldn’t help but wince at the sight of Archer mangling the lower half of a female mannequin with hedge clippers and smashing china plates and a small figurine of a ballerina with a hammer. The destruction of each object, flavoured by Archer’s recollections, was loaded with possible interpretations. Such wresting with the materiality of our surroundings was taken in a different direction in val smith’s offline onsite hook-ups. Extending their research into urban locations that might be considered queer, smith activated the large area of vegetation beside the Basement Theatre. Decked out in a fluorescent reflective safety suit, wearing a helmet complete with eye goggles and ear-muffs, smith delineated an idiosyncratic performance space through speakers playing new-age music and a row of dome-shaped LED party lights. A series of ascents and descents followed as smith could be seen walking through the car park, up along Mayoral Drive and then slowing falling and rolling down the embankment. What ensued was a slow-motion process of emergence. Entangled in vines, smith demonstrated the ways in which their surrounding environment could support, restrain or enable movement. For long periods of time smith could barely be seen, their presence indicated only by a rustling or sparkling from their LED-encrusted helmet. Peering into the lush, verdant expanse, trying to track smith’s progress brought to my mind a whole host of films and television series in which alien life-forms either malevolent or kind hide themselves in shadowy bushes, reluctant to reveal themselves.

Interestingly, smith’s suit echoed Houghton’s high-vis vest. These elements of costume lent the performers an air of authority as well as indicating a sense of risk or danger. In a recent reflection on the French phenomenon of the gilets jaunes, Will Wiles wrote of the semiotics of hi-vis, positing that the ubiquitous yellow vest conveys both visibility and invisibility. It signifies physical work, so that those who wear it present themselves as working class as well as conveying a sense of authority. The inclusion of such a garment introduces an interesting note of risk management into experimental dance: the message it conveys is that there are unknown hazards or dangers one might need to be protected from. I began to feel wary, and slightly more open to suggestions and commands from those wearing the authoritative attire. Hoping to successfully perform the role of a good audience member, I did as I was told and always obeyed instructions. However, my acquiescence, together with the presence of safety gear, brought to mind arguments made by performance theorist André Lepecki on his recent visit to Tāmaki Makaurau. Lepecki spoke of the ways in which societies of control invade the deepest recesses of consciousness, bodies and imagination, often with the aid of simple slogans such as “for your convenience” and “for your security.”[iii]

A sense of the workerly and provisional was extended in performances by Tru Paraha and Vicky Forest Kapo that occurred within the Basement proper. Both Paraha and Kapo included camping equipment such as tents and sleeping bags in their work. As part of Paraha’s 5th Body: xorcsm, dancers manipulated simple work lights and used small torches to draw attention to dark recesses in the theatre space. The trio of Kosta Bogoievski, Sean Macdonald and David Yates, clad in chaps, denim and fatigues, presented an apocalyptic band of deserting mercenaries performing grounded, earthy and angular movements. Anguish was frequently communicated as they held their faces in their hands, moved on all fours, and repeatedly thrashed the ground with a belt. An atmosphere of militaristic machismo was enacted, one filled with violence, torture and despair. As Macdonald roughly hooded himself with his own t-shirt I couldn’t help but think of kidnappings, disappearances, beheadings and the events that took place in the Abu Ghraib prison. Eventually the darkness was alleviated by healing acts of sticking kawakawa leaves on bodies, triumphant grands jetés and the haunting pirouettes Bogoievskiperformed whilst wearing the tent like a shroud.

“You’re going to suck my bones dry, aren’t you?” they asked, half laughing

The most arresting work of the week was Kapo’s #Performance. Though it also took place in the Basement studio, through the use of eye contact as well as direct address to audience members the performance produced an intimate atmosphere in which every action and utterance felt immediate, rich and profound. “Suck my bones!” Kapo casually said to their audience. “Roll my skin up.” Unfolding a sleeping bag, they took from it a series of metal rods that seemed to be components of a tent. Kapo manipulated these whilst telling a story, creating open and closed shapes, rudimentary structures, at one point they half-heartedly swung one around like a taiaha. Looking right at us they cajoled “Breathe!” We obeyed: each section of the audience made sure to audibly inhale and exhale as Kapo orchestrated our very bodies to enliven the space and provide them with a respiratory soundtrack. “You’re going to suck my bones dry, aren’t you?” they asked, half laughing. The little metal rods created black line drawings throughout the space; tent-like, they pointed to nomadic structures, ones created in provisional acts of settlement. A triangle formed by Kapo stood up like a maunga. I thought about how the frames of a tent are like the bones that Kapo kept mentioning, the draped plastic forms like skin. The narrative they told involved a friend being beaten to death, an incident made light of via its description as a kerfuffle. They tenderly hugged a large blue Swiss ball, telling it “I’ve got you…it’s OK” and in that moment they seemed to be attempting to soothe our broken planet. They then bore it upon their shoulder, kneeling like Atlas. “Breathe!” commanded Kapo again. Lying down upon the sleeping bag, Kapo pulled the material around them, covering their face so that it appeared to be a body bag. “Every journey has a good-bye,” they explained.

Resonating throughout all of these works was a sense of immanent collapse. Each performance seemed to be alluding to structures and environments that are either treacherous or in peril. A time of climate destabilisation requiring safety clothing and evacuations, an inherited economic system that seems untenable, a city in which service and assistance seem foreign, a series of delicate ecologies teetering towards imbalance, a world of discarded and wasted objects, planning and architecture that seems to dictate heteronormativity, the ubiquity of war, a nation deeply wounded by colonisation and a slowly dying planet. On the other hand, Experimental Dance Week temporarily brought together experimental practitioners in an attempt to create an atmosphere of support, empathy, solidarity and conviviality.

The seven days of Experimental Dance Week were relentless, each filled with a plethora of events including book launches, talks, workshops, pop-ups and performances. As if anticipating this excess, Houghton installed Post show recovery: After Show Recovery Portal in the Basement’s foyer. A small tent was cushioned with blankets and equipped with an LED chandelier, as well as two bright yellow lilos on which to recline. A sign at the entrance read: “Please feel free to enter the portal with a friend or artist or someone you don’t know for some gentle sounds from Te Wai Horotiu, the underground stream that flows under Queen St.” Lying on the lilo, listening to the sound of a stream, with closed eyes, I contemplated the nearby body of water, secret, invisible yet present. I felt sleepy, exhausted and content to perform the role expected of me and acquiesce to Houghton’s commands. For a moment I completely abandoned myself to experimental dance.

[i] David Hall. “Admit Nothing: Mapping Denial” in Reading Room: A Journal of Art and Culture 8 (Politics in Denial 2018): 82.

[ii] Additional information for this section was taken from Alys Longley, “Mistranslation as Method in Artistic Research” (publication forthcoming).

[iii] André Lepecki, “Imaginations, Speculations, Penumbral Vagrancies: Dance as un-doing of neo-liberal dis-experience” at the Undisciplining Dance symposium, 30 June – 2 July 2016, Dance Studies, National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries, The University of Auckland.