Always Something There to Remind Me: On Growing Up Amid Neoliberal Reforms

Mary Paul talks to six Generation X Aucklanders about growing up in Aotearoa during the drastic neoliberal reforms of the 1980s.

What was growing up in Aotearoa like during the drastic neoliberal reforms of the 1980s? Mary Paul talks to six Generation X Aucklanders.

In the early 1990s I often woke at night worrying about how our children would manage in a newly competitive world. If they couldn’t strive to be the best, or at least buy into the idea of life as raw competition, how would they manage? It was not so much a feeling of pressure as one of loss. Would there be a place for them to flourish – one organised around human values and community, and not only around competition and consumerism?

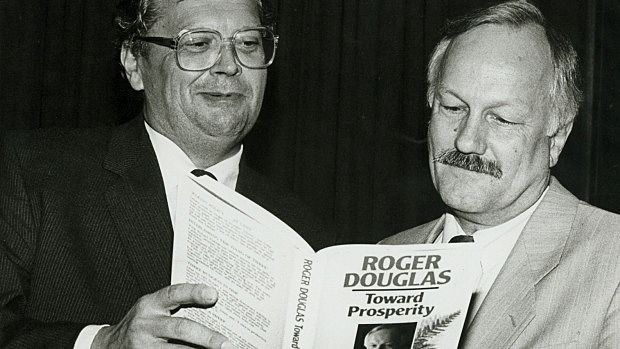

The country had changed in 1984, when a newly elected Labour Government implemented free-market reforms with extreme rapidity, reforms that were extended in the early 1990s by the subsequent National Government. What was done was oddly extreme for a well-developed Western democracy and an elected Labour government, or any government. However giving precedence to business did fit with the crude empirical generalisations that were current at the time about society being founded on self-interest.

I cannot find any developed economy in modern times that has inflicted so much harm on itself.

Economist Tim Hazeldine described the fallout as “terrible”. “I cannot,” he has written, “find any developed economy in modern times that has inflicted so much harm on itself. 104 major reforms pummel[ed] the body-economic. One manufacturing job in three was lost, and with those jobs basically went the blue-collar core that is crucial to the chances of less skilled workers being able to support their families in decency.” Between 1984 and 1991, unemployment tripled to more than 11%.

These policy changes were examples of free trade and globalisation typical at this period internationally, but our country was shaken more than any other because its ‘reforms’ were more extensive and a were complete U-turn – a seismic shift – from a protectionist planned economy to a laissez-faire one. State-owned assets and corporations were sold or partly sold – many to overseas buyers. With new market freedom it became more profitable to buy and sell shares or companies (and sometimes to asset-strip them) than to make products – so manufacturing and industrial jobs disappeared. And because the justification for all the changes was commercialisation and competition, there were no provisions or plans to replace jobs and social services.

A cohort emerged as affected by Rogernomics ... canaries in a mine.

Simon Denny, a paediatrician and health researcher who has also worked with Child Poverty Action Group, talks about the effect of the free-market reforms on New Zealand’s suicide statistics. In the 1950s, suicide rates were negligible but after Rogernomics there was an eight-fold increase. A cohort emerged as affected by Rogernomics. Denny thinks this is because young people develop their ideas of the future particularly from seeing their parents dealing with events. He describes young people as “canaries in a mine”. Denny thinks the poverty that resulted from unemployment in the 1980s and 90s is a much higher risk factor for suicide than ethnicity. In South Auckland in the 1980s, adult unemployment was 40 to 50%, and he can show that the graph of youth suicides numbers is almost identical to that of child poverty statistics.

Of course, Denny’s research doesn’t look at the disappearance of empathy or community, which might also correlate, but which is harder to measure.

For everyone, it was a changed society

I was 32 in 1984, when that Fourth Labour Government was elected. It has affected me, and my generation – for everyone, it was a changed society – but now I am more curious about the experiences of younger people – the contemporaries of the ones I was worrying about in 1990.

What follows are my conversations with six people, who are in the age group of my children, about what happened in their lives and how have they been marked by this extreme ideological shift and, for some, the resulting social trauma.

*

It’s hard to change with no one to turn to

Dominic Hoey was born in 1977 – the same age as my son. They met at Western Springs College. At 14 they were part of a group in the school cricket team who also hung out after school, playing Dungeon and Dragons.

Dominic’s parents were very aware of the implications of Rogernomics and saw David Lange as having betrayed them. They were left wingers, hippies even, involved in the Springbok Tour protests. His father was on the field in Hamilton when the game was called off. Apparently the Topp Twins were there and the organisers asked them to sing ‘Ngā Iwi E’ to help with the atmosphere.

The family’s house was in Grey Lynn, and except for some time in Melbourne and Dunedin, Dominic has continued to rent in that area and has seen it change and gentrify. Inter-generationally his family were also Aucklanders – at least on one side. His grandfather had done well, and built up a business, but the family was very large and they had little inherited support. His mother was not well for some of his childhood.

Dominic remembers schoolmates at Springs whose family had lost all their money (which had been a lot) and were living in a caravan, still affected by the 1987 crash. He also knew families living on benefits and recalls the effect it had when benefits were lowered in 1991.

At school, Dominic was hampered by problems with reading and writing (dyslexia was not a diagnosis in those days) though writing has since become central to his life. These days Dominic is a rapper, known as Tourettes, as well as a poet, novelist and playwright, well regarded in the scene of creatives that surrounds the Basement Theatre.

Dominic also works with rangatahi who have been excluded from the school system, helping them to write poems and prose about their lives, and express feelings and ideas. His former partner teaches them yoga and breathing techniques to help them face obstacles in their lives. Both are very aware that so much help and education has become a privatised commodity.

In his first novel, Iceland, Dominic tells the story of a young woman Zlata and her boyfriend Hamish. Zlata is in love with Hamish but, unhappy about his lifestyle and procrastination (ignoring his own artistic talents and letting friends down), she abandons him to go overseas. Hamish, who is in prison, has a hard time getting up from under his poverty, cynicism, shame and denial.

In a world of stereotyping, having friends or family who accept and don’t judge is crucial.

Dominic has experienced readers who ‘dis’ Hamish, the central character, as a loser who should be abandoned because he refuses to change. But, as Dominic puts it, that’s what it’s about: in a world of stereotyping, having friends or family who accept and don’t judge is crucial. Hamish has no support like this – and finds advice hard to take from his peers and girlfriend. “It is about it being very hard to change and move when you have no-one to turn to.”

We discuss how Dominic’s slowly emerging career has been accompanied by an increasingly challenging economic environment for someone wanting to be an artist without a wealthy family, or for anyone without a well-paid nine-to-five job and not driven by aspirational ideas of opportunity and wealth. Getting a flat is always a challenge. The other day he saw an ad for a room in a flat for $300! How could a waiter – or a writer – afford that rent?

Dominic is also one of the artists responsible for We Are Beneficiaries, an online life-stories project (begun by Sam Orchard) exposing the contempt people experience in the social welfare system. Dominic’s role as an artist seems to me to be about drawing attention to what is often unspoken about how we live, while in his teaching he uses his compassion and experience to help others who are struggling.

*

Quite a sad sort of place

Stephen (not his real name) was born in 1973. He didn’t grow up in Auckland but lives here now.

Stephen feels that New Zealand is “quite a sad sort of place now” – but not so much on his own behalf. He has two professional degrees and an interesting job that he is deeply committed to. He also has a family; his wife is in a professional job, and they own a house.

In the 1980s he knew what was happening but remembers feeling quite conflicted about the changes and thinking that they were “not very good, not New Zealand kind of things.”. He was not aware of the street protests against the selling of State Owned Enterprises, or factory closures, but he remembers vividly a school teacher stopping a maths class (this was in 1986 or 87, when he was 13 or 14) to tell the students about the terribleness of changes being proposed for schools (this must have been the Picot Report or the beginning of Tomorrow’s Schools, which disestablished the Ministry of Education and started competition in the sector). The incursion of adult life into school and the shock of the teacher interrupting a class remains vivid for Stephen.

Stephen also remembers that New Zealand “didn’t feel as safe,” and that if someone was in trouble they might get in more trouble – but also wonders if he felt like this because of his childhood experience of his parents separating, and also because of some resulting financial problems/circumstances for his mother. He doesn’t know.

... that Gen X feeling that the generation ahead of them succeeded because of being supported by certain institutions and then, as legislators, took away those institutions. Pulling the ladder up behind them.

Stephen loved David Lange and remembers meeting him. He saw him as a figurehead who genuinely represented the country, but saw Roger Douglas as a force for something not good. On reflection, he feels it is a bit of a tragedy that Lange was caught up in this – and that Rogernomics eclipsed what might have happened.

As someone who went to university in the 1990s, Stephen was caught by multiple policy changes to fees and loans. He never received a student allowance, because his parents were relatively well off and the Government had brought in means testing on allowances for students under 25 in 1993, and had reduced support for students overall. He began to specialise not long after the point when a flat fee for tuition – which had meant that fees for professional degrees such as dentistry and medicine were the same as for core arts and science degrees – had been abandoned, so he paid high fees. He finished studying in 2000, just a year before student loans were made exempt from interest while students were still studying. In 2005, he moved to Australia, again just a year before the government extended interest write-offs to former students – but only if you stayed in New Zealand.

So, all in all, he had a particularly frustrating experience and now, in his 40s, is still paying off his student loan. He contrasts himself with his older sister who “was paid to go to university”.

Stephen is aware of that Gen X feeling that the generation ahead of them succeeded because of being supported by certain institutions and then, as legislators, took away those institutions. Pulling the ladder up behind them. He is particularly derisive of Paula Bennett as the politician who earned a degree while on the Domestic Purposes Benefit (DPB), but when she became a cabinet minister removed the option for sole parents to study while on a benefit. “Hypocrisy that you receive something that you deny others, and you think that is okay. Something happened that made it okay to be like that – that has permeated everything – [the idea] that it is not the job of government to look after people.”

Rogernomics changed ideas – legitimised a much more brutal place, where people are perfectly prepared to be non-empathetic.

I ask Stephen again about that feeling of not being safe. He hasn’t personally felt less safe since those early days but knows that this is “contingent upon his personal ability to make his world safe”, which I think is a way of saying that safety now depends on individual and perhaps family abilities, financial and otherwise. There are modalities of freedom – freedom is not just one thing. All in all, he thinks the policies of Rogernomics changed ideas – “legitimised a much more brutal place”, where “people are perfectly prepared to be non-empathetic”.

Finally, I ask him, “What if Rogernomics had not prevailed?” Well – he answers – he spent time in Denmark, and it felt utopian. People didn’t begrudge the government helping those in need – that was OK there – but he doesn’t seem to think it would work in New Zealand. He thinks of Rogernomics as something that was sadly necessary – the economy had to change. His feeling is that if we had not done it to ourselves it might have been forced upon us. If it hadn’t happened? He is not sure, who knows – “Maybe economic collapse.”

*

A backward-walking hīkoi

For performance artist Mark Harvey, born in 1972 in Avondale, localness is important. I first met Mark at a small festival run by the arts collective Whau the People, in Riversdale Park, where he was leading a “backward-walking hīkoi” – though he was the only one walking backwards. The hīkoi turned out to be part performance art and part history walk.

Mark led our group to the house he grew up in, telling stories from his childhood and stories of then neighbours – including that all of the households in the street, except one, voted against the Homosexual Law Reform Bill of 1985.

Mark and his partner and two children have recently moved from Glen Eden to a small house in Titirangi. The section extends behind into a stand of covenanted kauri trees. Mark considers himself a kaitiaki of the bush, trapping possums and removing weeds.

Mark’s parents were both profoundly deaf. His father was a bricklayer and stonemason, and his mother a housewife – she couldn’t work because of her mental health. He and his older brother also spent a lot of time with their grandparents in Blockhouse Bay, sometimes living with them. His family, going back to his mother’s grandmother, had lived in the Avondale area since the 1920s. This grandmother was a land-owner and had five husbands but, as the family story goes, “feeling guilty, she left all her money to the church.” Though well off, they were socially committed. On his father’s side, his forebears were Methodist missionaries who lived at Kāpiti.

Mark is poised and serious – aware both critically and with pride of his descent from Scottish Calvinists and Portuguese Jesuit Catholics, and now thinking about what it means to have Māori ancestry – something he has just recently discovered from a DNA test.

People complain [about the early 1980s], that there was no choice, and of it being boring, but there was a sense of real stability.

Mark’s father owned his own business (quite rare in the Deaf community), and the family lived in a comfortable new subdivision near a thriving village shopping centre. They knew all their neighbours and people mixed together. There was no extreme wealth or extreme debt. “People complain,” he says, about the early 1980s, “that there was no choice, and of it being boring,” but there was “a sense of real stability.” The family was quite happy with things as they were. Everyone having a house from quite a young age. Consuming less.

Mark’s “Gramps” had been a specialist in education, working at the level of a principal, and was charged with bringing together services for children who wouldn’t go to school. His grandfather was dismayed by the now infamous Picot Report of 1988, which set the plan for Tomorrow’s Schools and discontinued (amongst other things) the oversight of specialist education. Mark recalls that his grandfather was “terrified a hole in the system” would open up and people would be lost.

The effects on his neighbourhood of shopping malls (St Lukes in 1968, and Lyn Mall in 1971) built shortly before he was born were intensified by the 1980s reforms, and Mark recalls factories closing and the Avondale village becoming ghostly. He also saw a group of ex-classmates hanging around in the streets. To some of Mark’s friends, totally convinced by the idea of a meritocracy, those kids were “bloody bludgers”, and poverty was “a scary monster”.

The closure of the mental hospitals nationally in the late 1980s was another feature of Mark’s growing up. Avondale was where Carrington Mental Hospital (formerly Oakley) was situated (now housing Unitec). This was the biggest mental hospital in New Zealand, and when the decision was made to close it, around 600 patients were rehoused in a community setting, mostly in boarding houses, called halfway houses. Don McGlashan’s beautiful cityscape song from the early 1990s, ‘Dominion Road’, references these boarding houses.

A suburb is a shell, and it changes who you get to meet when everyone is either at home or out of the suburb for recreation.

Mark recalls ex-patients around Avondale. Once, when he had just started driving, a woman ran out in front of him on the motorway, shouting, “Hey run me over, run me over, why don’t you? Run me over!”

Suburbs are different now, he reflects. “A suburb is a shell, and it changes who you get to meet when everyone is either at home or out of the suburb for recreation.”

Like others I talked to, family changes went along with economic changes. Following the 1987 crash, many people lost jobs and didn’t have money to renovate. His father’s bricklaying and masonry business folded. “The light went out,” Mark says. His father was on the dole for three months, before going to Australia to work. He lost morale and his health suffered. It was also at this time, Mark says, that his mother “gave up” on his father: “See you later, Reg!”

Leaving school in 1990 and determined to save money – inspired by a year in the US on an American Field Scholarship (AFS) – he took on four jobs in hospitality but couldn’t stand the graveyard shifts as a waiter and what he saw “as the new 1%” – “particularly the old men who were very, very, wealthy turning up in the early hours of the morning, each time with a different prostitute and expecting to be treated with deference.”

The 1991 “Mother of all Budgets”, introduced by National Government Finance Minister Ruth Richardson, cut benefits and removed their yearly adjustments ... benefits were re-set below a liveable level.

At university studying for a BA in the 1990s, Mark was given a name for his experience in the term “the neoliberal paradigm”. He recalls studying the 1991 “Mother of all Budgets”, introduced by National Government Finance Minister Ruth Richardson, which cut benefits and removed their yearly adjustments against cost of living. “Those who applaud the idea of small increases now don’t know the history of how benefits were re-set at that time, falling below a liveable level.” Mark also remembers this because it directly affected his mother, who was for a time on a solo mother’s benefit and latterly a sickness benefit.

Mark’s engagement in the arts was an extension of the looking at things from the outside that he had felt growing up, not wanting to go into the jobs that looked boring. After dropping out of his BA he trained as a dancer but didn’t like the way dancers were “objectified as beautiful bodies”. He also felt dance often served and reinforced the conservative status quo of audiences and he didn’t like the way “dancers were the last to be paid!”

To get away from that he moved into performance and visual arts, and education. In visual arts, too, there is “white-cube gallery politics” and he finds the Gibbs art collection sad. (Well-known personality Allan Gibbs, who prospered early in his business career from advising, purchasing and cashing up in the 1980s on the sale of a government department, now hosts a sculpture park north of Auckland.)

Taking part in the hikoi and then speaking with Mark, I felt his emotional commitment to memory – and his sadness and nostalgia for a safer society with more connections and less social suffering.

*

Better off barefoot

My next conversation is with Thomas Owen, not an Aucklander originally, but living here now. Thomas is a Senior Lecturer in Communication Studies at AUT and shares a small but bright and pleasant office on an upper floor of a modern high-rise in the city. We have been introduced by a colleague, Carla, who comes from Argentina and this is our first meeting. Maybe because of the South American connection, Thomas opens with the description of New Zealand’s economic revolution as “Chile without the guns”, which he remembers as a quote by David Harvey in his book on neoliberalism. He gestures at his bookshelf.

When I spoke to Carla she was surprised that New Zealand’s economic shift had not just been incremental – a creep – but rather extreme and rapid, and this is something Thomas concurs with. Though he is younger than some of the others I have spoken with (he was born in 1981), he remembers being aware of this as a child, because his father shared so much with him. I will hear lots more about his father in our conversation – you could say Thomas thinks aloud about his father as we talk.

Thomas grew up in Palmerston North, in Hokowhitu, “a nice neighbourhood” in “quite a beautiful part of town”, with a river and trees. There was “diversity within the suburb, with big old wooden houses alongside state houses”. Academics and workers. He remembers school as a real mix of people from these different backgrounds.

His father was older than his mother – when Thomas was born, he was in his late 40s or early 50s, and had had a life prior to his New Zealand one. He had only emigrated from London – where he had owned a sheet-metal business inherited from his father – in his 40s. Thomas knew little about his past life and always thought of his father as poor and working class – and of himself as less well off than his peers. It was a surprise when he learnt later that at one point in the 1970s his father had driven an MG sports car. The attraction of New Zealand, and Palmerston North in particular, was the access to open spaces and opportunities for mountain climbing and other outdoor activities.

In 1987, however, Thomas’s father lost his job as a draughtsman in an architecture firm – as Mark also observed, the 1987 crash curtailed a building boom. Around the same time, or just earlier, his parents’ marriage broke up. His mother, a nurse, was temporarily secretary to the Labour MP and remarried a much wealthier man. She later had a career as a nursing lecturer at polytechnics.

There was an acceptance that his father would never work again. Thomas also realises now that the house they lived in with their father was falling down, mouldy and cold, and with a terrible shower, but these were not things he worried about because his dad was a really creative person and fun to be with – he liked getting out and about. They had a small vegetable garden, and Thomas and his sister had their own rooms – though Thomas’s was a concrete sleep-out. Getting out included getting some sheets of plastic and going up Mount Ruapehu to slide down snow slopes, or going tramping, but with very old 1960s gear. Thomas remembers being embarrassed by his dad’s old cycle helmet.

Although their father was frugal and their life with him simple, in contrast with some wealthy friends as well as the step-dad, Thomas never felt excluded anywhere or worried. He never felt embarrassed by his father’s politics, but he also liked and respected his “bit more conservative” stepfather.

He recalls his father telling him he had got “the sack” and as a six year old thought this was a joke – about sacks.

Thomas very rarely saw any sign of his father’s bitterness. He recalls his father telling him he had got “the sack” and as a six year old thought this was a joke – about sacks. His father went on the DPB (as a sole parent’s benefit was then called) and also went to university, where he studied sociology and women’s studies – eventually doing a masters. In Thomas’s recall, his dad went on being really fun. He now realises that his father, in a three-year period, lost his job, his health (he developed diabetes) and his marriage.

As they drove round the countryside and outlying rural townships, his father would point out that a town such as Eketahuna used to be a “thriving community”. “People lost their jobs and had to move on. You will see it happening in other places,” his father told him. “This is terrible – this is a failure of democracy.”

Some of his mum’s relatives lived in Whakatu in Hawke’s Bay, where the freezing works had closed down in 1986. Thomas would hear about this from an uncle who was a respected member of the freezing works crew and, he thinks, a union rep. A cousin subsequently made a lot of money but remained living in the old family house right next door to the abandoned freezing works. Thomas’s dad enjoyed the extended whānau of these Hawke’s Bay relatives, and their generosity, and they respected his joining in to help dig a hāngi, though he didn’t fit in in all ways.

In his final year of school in 1999/2000, Thomas went on an AFS exchange programme to Spain, where he happened to live with a family of communists – “the real thing; the parents had been persecuted under Franco”. In addition to getting to know them, he also went to football games and experienced bull fighting.

The whisper around the schoolyard was that I would ‘fly’ through the air, because of the amazing technology of the Air Max.

The formative childhood experience Thomas comes back to is the contrast of wealth at his mother’s new husband’s house in relation to his dad’s. As an example of this “wealth” and loss-of-magic experience, he tells a story about a $300 pair of shoes – a lot of money in the early 1990s, when Thomas was 12 years old. At school they were all obsessed with malls, mufti days and “label bashers”. “I mowed lawns for a year to save $100, and my dad and step-dad put in $100 each. The whisper around the schoolyard was that I would ‘fly’ through the air, because of the amazing technology of the Air Max.”

So, he turned up to school sports day and word got around that the guy with the pair of Nike Air Max was about to do the high jump. Thomas recalls that he “crashed through the high bar like a front-row prop.” He could feel the dismayed gasp from the crowd because they also believed the lie.

Without the promised powers, the shoes became an albatross. A year later they were in the cupboard, and Thomas was dressing like Kurt Cobain and shopping from the op shops – old business shirts, Docs, woollen hats and jackets from 1960s and 70s.

Thomas says that ultimately this experience made him very sceptical of consumerism and the magic that advertising offers. He was aware of the pros and cons of the different opinions about society – but it was only when he studied neoliberalism that he understood what happened and that there were different possibilities.

He saw people crying and dumbstruck by losing jobs they had thought were forever ... he never wanted to be so attached to a job and way of life – not defined by those things.

We end with my question, “What if Rogernomics hadn’t happened?” He rephrases it as: “Could we have been a global player without that extreme and sudden alteration?” It seems that the character of New Zealand would always have been there – primary produce, farming, etc, so he feels, yes, and we could have developed more equally. What would we have missed out on? We would have had fewer millionaires. We talk too about the waste that comes from extreme consumerism.

At the teachers’ college in his Palmerston North suburb Hokowhitu, he saw people crying and dumbstruck by losing jobs they had thought were forever. He witnessed this several times, as there were a series of lay-offs. The message he took was that he never wanted to be so attached to a job and way of life – not defined by those things. It has made him different – or that is what he feels now. I am searching to understand this feeling and suggest the word ‘existential’. Thomas calls it wanting to “embrace precariousness” – not that he doesn’t love his work and feel loyalty to his university, but he doesn’t see it as eternally permanent.

When people tell him that they are buying a house he thinks they are deluded. They are not buying a house – the bank owns it, they are taking on debt, “renting from the bank”. His sense of the world is more impermanent. We end on his feeling that he is “better off barefoot”.

*

Shielded by other values

I talk to Richard Misilei and Mate Colvin at Tupu Youth Library in Ōtara where they both work – the name Tupu means new growth in Māori and various Pacific languages, a name given by the community to New Zealand’s only youth library. It feels like a place to grow, though quiet on a midday weekday. They lead me in behind the library desk through a gorgeously cluttered asymmetric office space. Two young women are busy at workstations laden with books, and the shelves are packed with paints and other activities. The back room where we sit down is cosy, too – a striped couch and armchair alongside a bike and a large black-and-red barbecue used on sunnier days.

I had approached Richard with my project a couple of weeks previously. I didn’t have an introduction, but libraries are a natural place for me, and Tupu seems a focal point of many communities in South Auckland. Luckily for me, Richard, who is the manager at Tupu, was interested in my request and also suggested talking to his colleague Mate Colvin, who is Kaikōri Ratonga Māori (Senior Library Assistant Māori Services). Mate has lived all her life in Ōtara.

Part of the ethos of both their childhoods was being protected ... this also meant their parents not talking to them about hardship or politics

Whatever Richard and Mate’s respective parents had experienced or thought of changes happening in the 1980s and 1990s, or ambitions they had to put on hold, they hadn’t shared with their children. Mate googled “Rogernomics” as she prepared for our discussion. Part of the ethos of both their childhoods was being protected – Mate calls it “sheltered”, Richard “shielded” – this also meant their parents not talking to them about hardship or politics, it seems.

Mate has made some notes and starts off with a forensic bent – what signs can we find in her childhood memories of the consequences of rapid economic and societal change? I don’t know that this is quite what I had in mind when I started on this project – it puts me more in the role of educator, which I hadn’t really intended, but we approach it as a joint investigation. Perhaps her and her friends’ fun activity at the supermarket – she and her younger brother would jump in to the skip bins to look for clothes – were a sign that her parents didn’t have much disposable income or money for treats.

Richard does recall comments on the price of food – and the shift from chicken legs to chicken backs. And his mother knowing a hundred ways to cook chicken – all of them delicious. Mate has similar memories of potatoes.

Most important in Richard’s and Mate’s growing up experiences are their families’ narratives and ambitions. Richard is the oldest in his family and grew up in Māngere – his father had come from Sāmoa in the early 1970s, wanting a better life. When he first arrived, he was living in Mt Roskill and belonged to the Methodist congregation at Pitt Street in the central city, so Richard remembers every Sunday when he was growing up the family would travel into the city. Also, his parents put up and supported other extended whānau as they arrived from Sāmoa – many of whom eventually moved out west. So although just his immediate family lived in Māngere, they had wider family connections across the city. Richard’s mother, unlike his father, didn’t choose to come to New Zealand. He describes her as “pushed to come to New Zealand” to escape rivalry, because her father had made more money than anyone else in the village. Richard’s parents met and married in Auckland.

Mate was born in 1984, grew up in Ōtara and has spent all her life there. Her family came to Auckland from the Bay of Plenty for better opportunities for the children and a chance for university. Mate explains: “Our iwi is Te Arawa – even though we lived in Auckland Mum wanted to make sure we knew our tūrangawaewae, so she took us home to Maketu most weekends. I spent school holidays there with my younger brother.”

Mate has four siblings; the oldest a brother, then a sister 11 years older than Mate, and finally a younger brother. Family from Bay of Plenty also visited a lot and, especially when she was young, relatives stayed with them. Mate’s father is Pākehā and from Invercargill.

“Mum was very involved in the Kōhanga Reo movement. She was involved in the establishment of Te Kupenga Kōhanga Reo, one of the kōhanga reo in Ōtara, where I was the first baby. My son attends Te Kupenga Kōhanga Reo now.”

Both Richard and Mate talk about the centrality and protectiveness of family and how they couldn’t really go outside and play on their own, as they see young kids doing now. Although Richard did play with neighbouring children – a tribe of kids – in the cul de sac where he lived in Māngere.

Richard says that Māngere has changed a bit – the biggest change for him being the library, and Three Guys supermarket becoming a Countdown at the Māngere East shops. Three Guys! We all laugh. At the Māngere Town Centre much has changed, with the Māngere Arts Centre and the new shopping precinct.

Mate notices a lot of physical change in Ōtara. The area around where she grew up used to be farmland. She also remembers show homes being built in new subdivisions and things going missing – built-in things, even toilets – a sign, she thinks, that people were struggling.

I tell them that statistics show that unemployment was very high in South Auckland in the late 1980s and 1990s. They don’t recall anything about that but do remember their parents working multiple jobs. Mate’s mother changed from volunteering at the kōhanga to paid employment there, and her father (starting from when she was about five or six) worked three jobs, which meant that she hardly saw him. But a precious memory is watching documentaries together – often war histories on the History Channel, as he chilled out after work – and learning things from him through discussing these. Now she can’t wait to discuss the history we are talking about with her father.

They had everything they needed when they were young but that things were done differently and involved less purchasing ... Shopping was not a leisure activity.

When I tell them about my own memory of the chilling effect of our mortgage interest rates going to 21% in the late 1980s and early 90s, they put that fact together with their parents working so hard at that time. Richard thinks 4.5% is bad enough! Knowing about the mortgage interest rates makes it more explicable that their parents couldn’t help with university fees. Richard and his wife, who have a four-year-old daughter, are paying a mortgage as well as his student loan. Richard’s father has been able to fulfil his ambition to train as a Methodist minister partly because his son also helped with paying the family mortgage.

Both Mate and Richard feel they had everything they needed when they were young but that things were done differently and involved less purchasing than now. Shopping was not a leisure activity. Mate remembers that their neighbour often made dresses and track suits for them. Also, you didn’t have many everyday clothes and best clothes were only worn on special occasions. We identify lots of values of frugality and creativity in their stories.

I tell them that one of the positive aspects people observed at the time from the free-market economy was the availability of cheaper children’s clothes. I also ask them about brands. Richard remembers Bata Bullets (the shoes worn in Taika Waititi’s Boy and by my own son) but Mate doesn’t know what we are talking about. She wonders, though, if not having the right gear was one of the reasons she was bullied at intermediate school and maybe one explanation for the bin raids.

Mate went to Rongomai Primary School – te reo Māori unit – total immersion. For intermediate she went to Clover Park Middle School (its new name is Kia Aroha College). “I was in the Māori area called Tupuranga. It was bilingual, we learnt both Māori and English.” But Mate also had problems at intermediate because after te reo Māori immersion from childhood she was told that her ability to read and write in English was not good enough. (Presumably no one said the same thing about the other students’ Māori.) However, she had the good fortune to be enrolled with the Correspondence School and found the written instruction she was sent brilliant. Mate’s school was ill equipped with computers; Richard’s had more than enough.

Richard doesn’t think he would have gone to university without a programme called Malaga – which was really a choir – an outreach summer programme established and run by the University of Auckland “to assist Pacific students and students in low-decile schools to realise their potential to access tertiary-level education”.

Mate was introduced to work by her mother early on. She worked at the library and studied part time. She also learned lots of useful skills from her dad: “tack welding, that was my favourite skill!” She obviously loves her job at Tupu, where she has worked for 17 years. When I comment on how important libraries are in the community, Richard tells me a story from his wife, also a librarian. “The other day an old lady came in to the library when she was robbed – rather than going to the police.”

Kindness, respect, being grateful, sharing, humility were important values in our family, these were instilled into my way of life from as far back as I can remember – these are also a very big part of Māori culture.

Both Mate and Richard have come from strong families who have also acted as support to others. Mate looks at a couple of the ideas that I suggested were the rhetoric of the free-market revolution: “for there to be success there must be failure”, “you only value what you pay for”. She says the latter doesn’t mean anything to her, her whānau and beyond. “Kindness, respect, being grateful, sharing, humility were important values in our family, these were instilled into my way of life from as far back as I can remember – these are also a very big part of Māori culture.”

It is almost as if these two have avoided the repercussions of 1984 – although they didn’t really, because they are now working and paying off debt in an expensive environment and a low-wage economy, but their own family, Sāmoan and Māori values predominated. Also, they both work in a library – almost the last remaining non-privatised social provision.

I mention that there is sometimes contempt for those who are in trouble. That was what Metiria Turei meant when she spoke about punitive policies in the Ministry of Social Development. Mate looks startled – Metiria, yes, she knows the name but not really anything about what she spoke up about. (She laughs at her age group’s lack of interest in politics.) Richard nods, and adds “shame” into the mix of the emotions involved in not doing well or needing help. For example, he says, “All my mates had branded clothing – Nikes, Reeboks, Fila, etc. We couldn’t afford anything like that so felt shame when we had mufti day at school.”

As we finish the interview, Mate is bubbly. She is going to talk to her father. It is unusual on a workday to share life stories and wonder about history.

You’re not a loser/ You’re a human/ And I love you

These stories are so much only a beginning. When I decided to write this essay I wanted to travel around the country and speak to people who grew up during Rogernomics in places like Whanganui, Gisborne and Dunedin. Now that I am finishing the conversations, I feel it is right that I have been listening to people from my own city.

My conversations trace a kind of map of Auckland and beyond. Some of the things that I hadn’t thought about enough before were how people in particular geographic areas, rōhe, suburbs and cities were affected – particularly whole communities. I hadn’t remembered about people moving – families moving from areas with no work to cities, families moving to Australia, New Zealand citizens arriving from the Pacific Islands, Pacific Island families moving across Auckland. Even the moving of my own family from Wellington to Auckland – I had forgotten it happened as a consequence of new market funding policies for the arts.

On RNZ ‘Mix Tape’, as I am concluding this, I hear Phoenix Foundation’s 2015 song ‘Give Up your Dreams’. The song feels like a modest and humorous riposte to the aspirational and increasingly corporate world that has tried to persuade people that they and their dreams can be larger than life – and go hang the rest. It’s also a love song that refuses the tags of success and failure and seems to me to fit with the mood of the people I have had the privilege of talking life history with.

Don’t let anyone tell you that you’re special

Don’t let anyone tell you that all your dreams will come true

Don’t let anyone say that the world is your oyster

The world is not an oyster

The world is a cold, dark planet floating through infinite space on a ceaseless journey to its own destruction

And all we can do about it is be alright about things and get on with stuff

You’re not a loser

You’re a human

And I love you

I love you

Give up your dreams