April Reading

The Race That is Not About Winning by Mark Oppenheimer | The Believer (April, 2011)

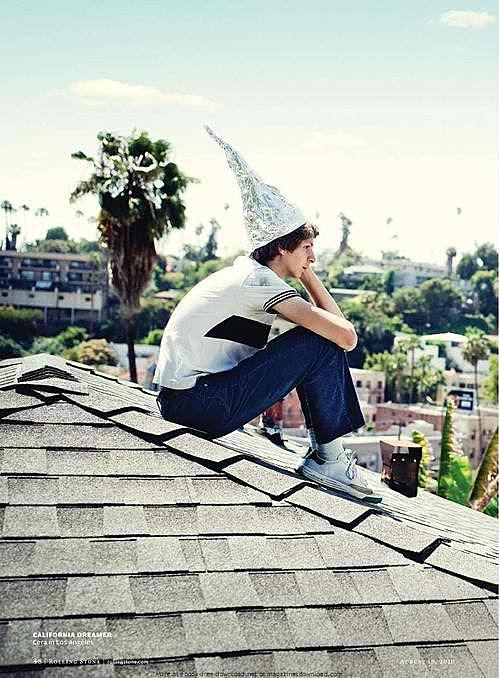

I’m not a fan of Michael Cera. I don’t hate him, but I don’t like him. Okay, I liked François, his character’s alter ego in Youth in Revolt, and I couldn’t tell you how many times I’ve seen his Two Ferns interview with Zach Galifianakis, but most of the time I can’t stand him, with his squeaky soft-spokenness and his endearingly nervous banter, and I’ve tended to dismiss him as a sort of pre-puberty Jesse Eisenberg. But after reading Mark Oppenheimer’s beautifully written tribute to him and the character archetype he embodies, I have a newfound appreciation for the guy.

All runners are at heart mediocrities, bad even when they are good.

In general, teenage distance runners have no sense of themselves as part of anything bigger, any grand tradition. During my four years of competitive running, I never subscribed to Runner’s World magazine, never learned the names of any marathoners, never aspired to do anything with my running beyond earn a varsity letter, make some friends, and maybe have a dalliance with one of the girls on the girls’ cross-country team. We were shiftless and indifferent.

All of which is just to emphasize my gratitude that one of the most common real-life nerd-types, and the one closest to my heart, has at last found its screen embodiment. After all, most nerds are not brilliant computer wizards. Most nerds are not stutterers, either, and most do have female friends, if only because at large schools there are female nerds to ally with (cf. Michelle Meyrink in Revenge of the Nerds, Real Genius, and a brilliant arc on Family Ties). With Cera, we at last have an actor who effortlessly honors the American teen male anti-athlete, a boy who populates so many high-school cross-country teams. He is not a genius, he is not pathologically shy, and he is not widely loathed. Rather, he is a little shy, a little marginal, and a good bit quirkier than his classmates. He does not necessarily read constantly, but when he reads—or listens to music, or skips school to go to a matinee by himself—it is with an outsider’s wistfulness, with a hopeful eye on the world beyond high school. He is a character who resonates with a kind of kid—and that kid is everywhere—who turns to movies for reassurance that he is not alone. That boy wears short shorts, and he runs.

The Information Essay | n+1 (April, 2011)

We are constantly bombarded with information, and - as David Shields suggests in Reality Hunger - our appetite for this is increasing. Building on this, this piece muses on our overabundant repertoire of facts and how this - as manifested in both writer and reader - is impacting on approaches to literature.

As James Wood observed in 2001, ‘knowing about things’ has become one of the qualifications of the contemporary novelist. Still, the research novel mostly subordinated its facts, even as these increased in density, to plot and character. What we begin to glimpse in recent years, especially in “literary nonfiction,” is something different: the evolution of a style that resembles “information for information’s sake,” in something like the art for art’s sake of 19th-century French decadence. What can this new literature of information be saying? The nature of facts is supposed to be that they speak for themselves. The nature of literature of course is the opposite — that it always means more than it says.

Unlike the traditional, Kantian sublime, which supposedly restored us to a knowledge of our own freedom of will and mind in the face of the infinite and amazing, here the entire vast machine of knowledge serves only to remind us that we’re trapped within an inescapable totality.

The Lost Boys by Skip Hollandsworth | Texas Monthly (April, 2011)

The oft-forgotten story of Dean Corll, a timid candy man from Houston who, from 1970 to 1973, kidnapped, tortured, and murdered at least 28 young men. One of the interesting aspects of this case is that he had two teenage accomplices - Wayne Henley and David Brooks, who helped him lure boys into his white van by offering them rides or beer. Both Brooks and Henley saw Corll as a father figure - someone who treated them better than their own fathers - but as his appetite grew, so did the boys’ reluctance to be involved with him any longer, and the last words Henley said to Corll before shooting him was “I can’t have you kill all my friends.”

Farther Away by Jonathan Franzen | The New Yorker (April 18, 2011)

A gorgeous piece by Jonathan Franzen on living a life of solitude and dealing with the death of his friend, David Foster Wallace. Set within a trip to Masafuera - a rocky, unforgiving island off the coast of central Chile - where Franzen birdwatches, re-reads Robinson Crusoe and scatters his friend’s ashes, this piece is cautiously generous in the insight it offers and you get the sense that this essay is as much for him as it is for his readers.

The mastery with which he weaves the personal with the political is as evident here as it is in his novels, and his descriptions of his time on the island, the literary context within which Robinson Crusoe was produced and his remembrance of Wallace are seamlessly melded. But what really makes this piece worth reading is Franzen’s account of his friendship with Wallace, a bond marked by love and anger, by frustration and dependency.

David wrote about weather as well as anyone who ever put words on paper, and he loved his dogs more purely than he loved anything or anyone else, but nature itself didn’t interest him, and he was utterly indifferent to birds. Once, when we were driving near Stinson Beach, in California, I’d stopped to give him a telescope view of a long-billed curlew, a species whose magnificence is to my mind self-evident and revelatory. He looked through the scope for two seconds before turning away with patent boredom. “Yeah,” he said with his particular tone of hollow politeness, “it’s pretty.” In the summer before he died, sitting with him on his patio while he smoked cigarettes, I couldn’t keep my eyes off the hummingbirds around his house and was saddened that he could, and while he was taking his heavily medicated afternoon naps I was studying the birds of Ecuador for an upcoming trip, and I understood the difference between his unmanageable misery and my manageable discontents to be that I could escape myself in the joy of birds and he could not.

He was sick, yes, and in a sense the story of my friendship with him is simply that I loved a person who was mentally ill. The depressed person then killed himself, in a way calculated to inflict maximum pain on those he loved most, and we who loved him were left feeling angry and betrayed. Betrayed not merely by the failure of our investment of love but by the way in which his suicide took the person away from us and made him into a very public legend. People who had never read his fiction, or had never even heard of him, read his Kenyon College commencement address in the Wall Street Journal and mourned the loss of a great and gentle soul. A literary establishment that had never so much as short-listed one of his books for a national prize now united to declare him a lost national treasure. Of course, he was a national treasure, and, being a writer, he didn’t “belong” to his readers any less than to me. But if you happened to know that his actual character was more complex and dubious than he was getting credit for, and if you also knew that he was more lovable—funnier, sillier, needier, more poignantly at war with his demons, more lost, more childishly transparent in his lies and inconsistencies—than the benignant and morally clairvoyant artist/saint that had been made of him, it was still hard not to feel wounded by the part of him that had chosen the adulation of strangers over the love of the people closest to him.

The people who knew David least well are most likely to speak of him in saintly terms. What makes this especially strange is the near-perfect absence, in his fiction, of ordinary love. Close loving relationships, which for most of us are a foundational source of meaning, have no standing in the Wallace fictional universe. What we get, instead, are characters keeping their heartless compulsions secret from those who love them; characters scheming to appear loving or to prove to themselves that what feels like love is really just disguised self-interest; or, at most, characters directing an abstract or spiritual love toward somebody profoundly repellent—the cranial-fluid-dripping wife in “Infinite Jest,” the psychopath in the last of the interviews with hideous men. David’s fiction is populated with dissemblers and manipulators and emotional isolates, and yet the people who had only glancing or formal contact with him took his rather laborious hyper-considerateness and moral wisdom at face value.