The Art of Protest

Ten New Zealand artworks from ‘Protest Tautohetohe: Objects of Resistance, Persistence and Defiance’

An extract from Protest Tautohetohe: Objects of Resistance, Persistence and Defiance, edited by Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams and Puawai Cairns.

Protest has always been, and continues to be, everywhere. It is at the core of democracy and a critical tool of citizenship. Diverse, dramatic, colourful, challenging, compelling, transformative; protest is also highly contested and controversial.

This nation has a long and rich history of objects, images, symbols and slogans made by activists and social movements seeking to combat injustice and change the status quo. They range from protest objects seen out in the street — banners, placards, posters, billboards, T-shirts, badges, stickers and graffiti — to objects and strategies from behind the scenes, such as petitions, artworks and hidden diaries. As images, some have become indelible: the now iconic Halt All Racist Tours’ split-heart symbol, for example, or the slogan ‘Keep New Zealand Nuclear Free’ and the tino rangatiratanga flag. Protest Tautohetohe: Objects of Resistance, Persistence and Defiance brings these objects, slogans and images to the centre of the frame.

Two sides of Parihaka

Lily Aitui Laita (Ngāti Raukawa ki te tonga, Sāmoa) is an Auckland-based artist and arts educator whose practice includes painting, printmaking and sculpture. She has exhibited throughout Aotearoa.

This work, Pari’aka, was made in a day and a half, after Laita made an enlightening visit to Parihaka in 1989. As she recounts: ‘When Tamasese (one of the leaders of the independence movement in Western Sāmoa called the Mau) was exiled and brought over here to Mount Eden prison, people from Parihaka came up and supported him because of their beliefs. His people reciprocated over the years and brought gifts when they stayed at Parihaka.’

Pari’aka – its name reflecting the Taranaki dialect – is a triptych featuring her great-grandfather Aitui Ta‘avao on the left (a member of the Mau independence movement) and referencing the prophets of Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi on the right. The central panel depicts Laita herself (morphed with Taranaki and the three feathers), her arms reaching into the panels on either side.

Smoko masterpiece

‘Have filled one drawing book with colour notes and sketches of pickers during smoko and lunch hours, and my head is full of possible masterpieces,’ wrote artist Rita Angus in a letter to her sister Jean. She was writing from Nelson, where she was part of the seasonal labour force that harvested apples, tobacco and hops across the region, work favoured by artists as a means to supplement their art practice. Angus picked tobacco at Pangatōtara in fields that were depicted in works by fellow artists Colin McCahon and Doris Lusk.

This painting, The Apple Pickers, has a level of complexity uncommon in Angus’s work (for example the twelve workers at rest amongst the apple trees on an orchard in the Upper Moutere). In the background, beyond the orchard and hills, is the distinctive white-capped peak of Mount Arthur.

Angus was a pacifist and in 1944 she spent time at the Riverside Farm (now Riverside Community), which was established in 1941 by a small group of Christian Pacifists who, ‘in the face of the 2nd World War, were eager to practise ways of communal living that were based on cooperation and sustainability and the repudiation of war’.

This painting, though unfinished, presents an idealised scene in which the landscape, weather and subjects all appear at peace. Not represented in Angus’s painting is the reality that many of the men of Riverside Farm were imprisoned as conscientious objectors and put to work on other farms for the duration of the Second World War.

World Court Project quilt

This protest quilt, designed by Joanne Bains for the World Court Project in 1994, calls for a ban on all nuclear weapons, and an ‘Independent and Nuclear Free Pacific’. The project was initiated by New Zealanders who took the issue of whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons was legal to the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion.

The panels depict a range of Pacific and New Zealand plants, animals and nuclear issues. The Rainbow Warrior is acknowledged top right. Other issues are included in the quilt, including apartheid, United States military bases, pollution and extinction. The two largest central blocks are tivaevae (patchwork and applique quilts) made by Cook Islands women in New Zealand. Secondary school art students also helped make some of the panels. The Sāmoan language inscription on the lower border translates as ‘International Year of World’s Indigenous People’, which had taken place the previous year.

The soft, tactile, colourful and visual qualities of quilts can make them non-threatening but effective protest objects, translatable across cultures. This quilt was toured nationally and internationally. Thousands of cards depicting it were sold to fundraise for the World Court Project. In October 1995 it was displayed at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, when New Zealand’s ‘Declarations of Public Conscience’ were presented.

On 8 July 1996, the International Court of Justice delivered its finding that the ‘threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law’.

Not going away

‘I remember when the Crown went around the country to talk about the Fiscal Envelope. This was the government offering a lemon on the settlement of historic grievances.’ During hearings in 1995, Tame Iti (Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Wairere, Ngāti Hauā, Te Arawa) made what he describes as a ‘counter-offer’ for the return of our land: his nephew’s horse blanket. Four years later, Iti was made aware that the blanket was now hanging, framed, on a wall in the workplace of the Office of Treaty Settlements (OTS), but Tūhoe land had not yet been returned. In response, Iti invoiced OTS for $11,250. This gesture was not about the money but rather about reminding the Crown that Tūhoe were still present, were still waiting for the return of land, and were not going away.

Defending the foreshore

A cast-iron sculpture weighing 185 kilograms provides a powerful commentary on the controversial passing of the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004. The Act was viewed by Māori as yet another example of the Crown denying Māori rights to land. The introduction of this Act was prompted by a 1997 Māori Land Court case where Marlborough Māori applied to have the foreshore designated as Māori land. Before the case was heard, the High Court ruled that not only would Māori customary interest to dry coastal land be lost once purchased by the Crown but also that the seabed had always been owned by the Crown. The case was subsequently taken to the Court of Appeal, which ruled that the case could be heard by the Māori Land Court, but before it could be heard, the Foreshore and Seabed Act was passed by government. The Act now required Māori claimants to prove their customary rights had been in continual practice since 1840, a threshold that was seen as nigh on impossible to prove.

With Foreshore Defender, artist Dr Brett Graham (Ngaati Korokii Kahukura) reappropriates a shape that has violent connotations, a military stealth bomber, to remind viewers of the repercussions that come when land is lost by Māori. The determination of the Crown that the ownership of the foreshore and seabed remains in government hands and the subsequent passing of such an Act of legislation, before Māori can even have their case heard before the court, was astonishing to behold. This work takes a military weapon, whose very purpose is to remain undetected, and chisels into its skin patterns drawn from whakairo, thereby transforming the bomber into an agent for the betterment of Māori. The work continues in the tradition of adaptation that Māori have always used, speaking specifically to Māori identifying Western symbols of power and then imbuing them with Māori meanings.

Te whare tangata

Artist and illustrator Robyn Kahukiwa (Ngāti Porou, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Hau, Ngāti Konohi, Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare) began painting while caring for her two small children. Having grown up in Australia, Kahukiwa moved to New Zealand at the age of nineteen and has exhibited widely since 1972. Her work has often been inspired by, and depicted, wāhine Māori and atua wāhine, their mana and mauri resplendently celebrated. Through her work, she also explores the harsher aspects of te ao Māori: the geographical dislocation that comes from international and national migration. Through her work she negotiates these spaces herself, maintaining a strength of connection that cannot be doubted.

This work references the burying of whenua (placenta) in whenua (land) after a baby is born. This tikanga often sees whenua being taken to one’s tūrangawaewae, but how do you practise this tikanga if you have no connection or knowledge of your tūrangawaewae? This painting depicts that pain of displacement while strongly asserting that that connection is still present in the knowledge of the tikanga. It is also a strong assertion of the position of a Māori mother, of her role as the whare tangata.

Gender diversity

The ‘Indigenous genders are real’ poster above left challenges the idea that there are only two genders and affirms diverse genders across cultures. The powerful and positive image is a portrait of a Native American person who lived in New Zealand, and was created by the artist known as Ariki Arts – Taupuruariki (Ariki) Brightwell (Rongowhakaata, Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare, Raukawa, Rangitāne, Tahiti).

The ‘Trans people have always existed’ poster above right challenges the belief that heteronormativity is the original and natural state, and affirms that being trans is not a new trend. The illustration is by Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho (Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Porou, Rongowhakaata, Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi, Ngāti Kahungungu) who is a takatāpui activist artist.

These two posters are part of a suite of eight published by Gender Minorities Aotearoa, which is a cross-cultural and transgender-led organisation, assisting and advocating for transgender, intersex and takatāpui people. The posters aim to help break down the isolation trans people can feel, particularly in smaller centres, and as such have been displayed from Invercargill to Whangarei.

Posters are a traditional method of advertising, but posters in the street are not easily ignored, and can catch the eye of people who may not be aware of trans people and issues around representation and prejudice in their communities. Such messaging can also gain acceptance and traction when displayed on authorised hoardings.

Barricades, 2007. By Dane Mitchell. Purchased 2010. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (2010/2.1–30)

Barriers in the gallery

In 2005 artist Dane Mitchell began research as part of a project at Galeria do Centro Cultural Maria Antonia, São Paulo University, Brazil. During this research he found an image of a civilian-built street barricade erected during an uprising in Brazil in the late 1960s. For the artist, the hastily arranged barricade of objects operated on both a physical and symbolic level. The barricade depicted looked unlikely to be able to prevent anything; the sentiment behind its construction was evident.

Barricades proper started as part of an archive of over three hundred images of civilian-built barricades from around the world. As the artist states, ‘... these hastily assembled barricades are ruptures in this obsession with policing of social boundaries through architectural means’. This quote holds more resonance when considering its expression in a gallery setting in which the walls are cut out of and transformed into makeshift shields, a shovel is repurposed into a agpole, and other objects are gathered and reconstituted into fortresses. Even the aggressive object that is the Molotov cocktail is transformed, transmuted by a monotone of white.

It is easy to derogate artwork that attempts to activate such sterile spaces (in contrast to protest on the streets). Yet Mitchell is an artist with a huge international platform, one he is employing to speak about the material culture of protest and its rough-and-ready nature.

(Influ)enza, 2008. By Siliga David Setoga. Courtesy of the artist

Exporting influenza

As has been explored elsewhere, New Zealand has long benefited from the seasonal labour force that Pacific Islands provide. However, for Sāmoa, the relationship between the two countries dates back to the trusteeship that New Zealand had over Sāmoa from 1918 to 1962, after seizing the country from German control at the request of Britain in World War One. As part of this trusteeship, an export relationship also formed between the two countries. A legacy from this time is the influenza epidemic carried to Sāmoa from New Zealand in 1918; approximately one-fifth of the Sāmoan population died – 8500 people.

This work from Siliga Setoga makes reference to this legacy by appropriating the highly recognisable ‘enza’ logo and adding the pre x ‘in u’ to reference the role that New Zealand had in the spread of influenza in Sāmoa. This work operates on multiple levels, bringing the history of New Zealand’s role in spreading the virus to the fore, while also adding in a commentary about how the labour force continues to be filled by workers from Sāmoa.

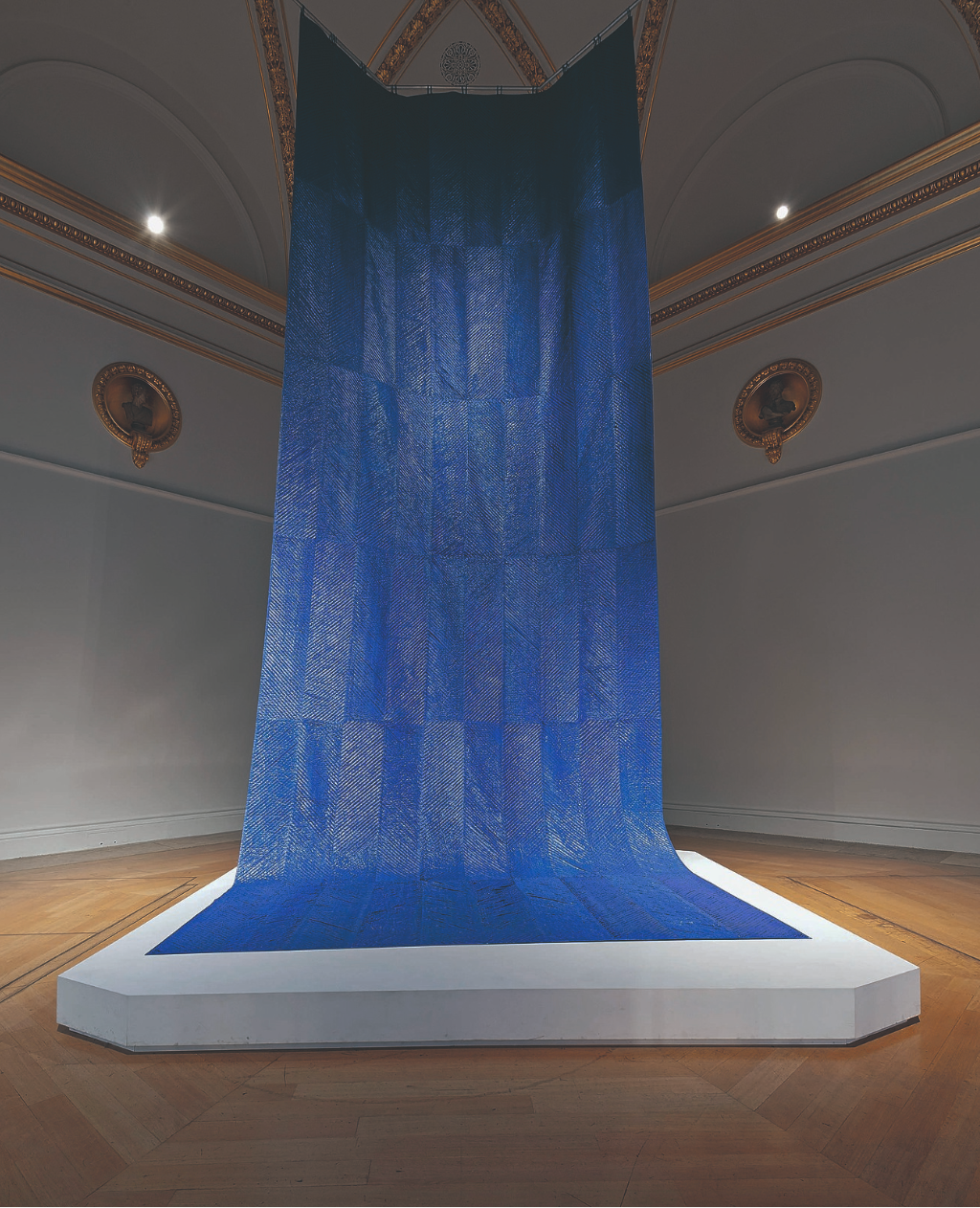

Kiko Moana, 2016. By Mata Aho Collective. Purchased 2017. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (ME024286)

Taniwha as guardians of water

Kiko Moana, a large-scale installation work by the Mata Aho Collective whose members are Erena Baker (Te Ātiawa ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Toa Rangatira), Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe), Bridget Reweti (Ngāi te Rangi, Ngāti Rangihui), Terri Te Tau (Rangitāne ki Wairarapa). The work draws on the concept of mana wāhine, which denotes the inherent power of wāhine as derived from their ira wāhine. It is made from blue tarpaulin, as Mata Aho prefer to use utilitarian material that many whānau will use in their everyday lives, a point that is explored in their Instagram account. This work was made for documenta 14, an art exhibition held in Kassel, Germany, every ve years. The colour of the tarpaulin is reminiscent of water but the style in which the material has been prepared elevates this symbolism in a manifestly tactile way. The title itself encompasses the way in which the work relates to both water and taniwha in that ‘kiko’ speaks to substance and ‘moana’ speaks to water. It can thus be read that Kiko Moana is a physical embodiment of water, perhaps a taniwha that both lives in, and is personified by, water.

This work thus speaks not only to water – the material evoking conversations around this seemingly unconventional choice – but to its degradation. Plastic, that ubiquitous material of convenience, is one of the worst polluters of our oceans, and that pollution is part of the commentary the collective raises with this work. So too does this work speak of the intergenerational passing of knowledge; the collective worked with senior wāhine Māori artists and academics in making this work, discovering that Māori had a practice of sewing before the arrival of Europeans. That discovery is a commentary the work makes: as our environment has progressively degraded as the result of industrialisation and as mass production removes the need to make our own clothing, the knowledge of makers of Māori arts is ever more important. Works like Kiko Moana help to revitalise that knowledge.

Protest Tautohetohe: Objects of Resistance, Persistence and Defiance, edited by Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams and Puawai Cairns, is published by Te Papa Press.