Speaking Power to the Truth: The Political Assassination of Metiria Turei

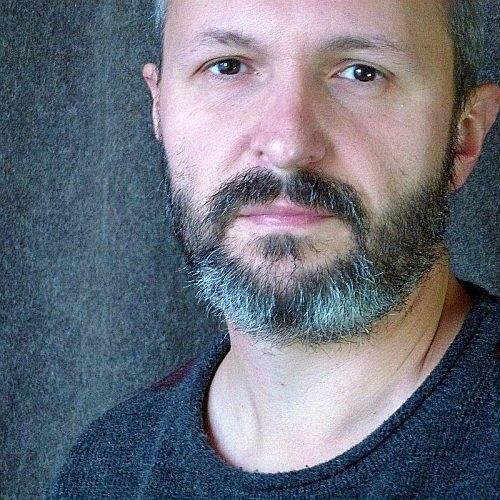

Giovanni Tiso on New Zealand media and the swimming of sharks.

Giovanni Tiso on New Zealand media and the swimming of sharks.

“I don’t know how else to describe my life.” This line, spoken by Green Party Co-leader Metiria Turei (Ngāti Kahungunu) during her fateful interview with John Campbell, sums up the trajectory that led to her resignation. It was an arc that fully illuminated the workings of our media: what it chooses to investigate, and how; the question it chooses to ask; the answers it will accept and the answers it won’t.

It is sadly appropriate that Turei’s last stand happened during Checkpoint, the show hosted by the media personality with the greatest reputation for socially committed journalism, therefore most likely to lend her a sympathetic ear. “By god this is a tough conversation to have,” he intoned before asking again if Turei had received money 25 years ago from the mother of her ex-partner. This was the line of questioning that had been pursued by every other major outlet over the course of three weeks. Had it been anyone else who brought it to its conclusion, we may harbour some residual illusion that not all journalists would behave in that way, or be insensitive to the implications. But with Campbell, you knew it was as good as it gets.

You also knew that it didn’t matter what Turei said, she was done. The questions wouldn’t stop, and her answers would cease to matter. There is no public life, let alone a political life, that can withstand that kind of interrogation and still lay claims to honesty and truthfulness.

There is in fact nothing natural, inevitable or necessary about this narrow understanding of journalism, which has no regard for social value.

In refusing to blame the media for his co-leader’s resignation, James Shaw remarked that “some of the interviews have been really tough, but they should have been tough,” because journalists were just doing their job. The problem with this line of argument is that it either buys into Finlay Macdonald’s claim that Turei “played her hand poorly” (which seems doubtful), or it implies that she had no hand to play at all. And if this is the case, then life as a welfare recipient who cheated on how many flatmates she had would be the kind of past politicians are simply not allowed to talk about. Not unless they are prepared to face a backlash that is entirely predictable, and that a professional operator ought therefore to predict. As Macdonald ungenerously put it: “What the hell did she expect?”

There is in fact nothing natural, inevitable or necessary about this narrow understanding of journalism which has no regard for social value. What good is it to anyone when a politician is brought down not because she didn’t tell the truth, but because she failed to control the narrative? And whose interests are being served, when the issue she had risked so much to raise was endemic poverty and the systems that ensure its perpetuation?

Having allowed itself to become the mirror image of realpolitik, this journalism is no longer a means, but an end: another set of rules for people who aspire for power to play by, with no ethical grounding in the wellbeing of the polity. If it seems like the only game there is, it is because we have stopped conceiving of any other possibilities. But we don’t need to hark nostalgically to a long-lost past or move to another country to find a working alternative: we just need to look at Māori media. Both the strongest condemnations of the treatment of Turei and the deepest critiques of its ideological nature have come from Māori voices, including academics Leonie Pihama and Khylee Quince, journalist Yvonne Tahana and writer Miriama Aoake. At the same time, Māori reporters such as Mihingarangi Forbes produced very strong work that provided context for Turei’s revelations and for the welfare reform proposal they were originally meant to introduce, whilst also pulling into the orbit of the official journalism some of the thousands of deeply moving personal stories that appeared on social media under the hashtag #IamMetiria.

This was the point in the interview that underscored most forcefully the value of those race-based critiques, reminding us that a greater standard of morality is required of Māori, and that when they are poor they must not only be deserving, but the most deserving of all.

In a bitterly ironic twist, one of Forbes’s reports for Checkpoint was used by Campbell to force Turei into admitting that her situation wasn’t as dire as that of other people on the benefit – a claim she had in fact never made. This was the point in the interview that underscored most forcefully the value of those race-based critiques, reminding us that a greater standard of morality is required of Māori, and that when they are poor they must not only be deserving, but the most deserving of all. In this context, the insistence by some critics that Turei played her hand poorly is equivalent to charging her with failing to account for institutional racism – which in turn is a very small step away from blaming her for racism.

Coverage up to that point from mainstream Pākehā voices had been dominated by a mix of resentment, beneficiary bashing and stern condemnation of Turei’s moral judgment. “What about all the women who feed their children on less?” asked Tracy Watkins, who’s never had to feed her children on less. “Mainstream opinion is deeply disturbed” declared a New Zealand Herald editorial, apparently unaware of the role that New Zealand Herald editorials have in shaping mainstream opinion. “If Metiria Turei is typical the system sounds not so bad,” said John Roughan, who thinks child poverty statistics are misleading because they don’t “gel with the kids we see around”. Then came Patrick Gower ("her political fraud is ripping off the New Zealand public"), Tim Beveridge (Turei displayed "the new essential Kiwi value, dishonesty"), John Armstrong ("she will be remembered but she won’t be missed," possibly the most bile-filled editorial of all). And, of course, we couldn’t fail to hear from Mike Hosking, who informed us that by failing to dob in all the people who had shared their stories with her, Turei was now “a co-conspirator to others ripping off the system”.

As for Turei’s supporters on social media, alongside some sympathetic coverage they were either ridiculed – for instance by Leighton Smith – or dismissed as the product of an echo chamber, as if newsrooms or the parliamentary press gallery had a special, unmediated access to what ordinary people think, and weren’t echo chambers themselves.

This very partial catalogue serves as an illustration of how the media is instrumental in the gendered and racialised criminalisation of poor people in Aotearoa.

This very partial catalogue serves as an illustration of how the media is instrumental in the gendered and racialised criminalisation of poor people in Aotearoa. Far too often – while rightly worrying about the continued capacity of journalism to serve its democratic functions in spite of the decline of its business model – we forget that the fourth estate is just that: an estate, that is to say a seat of power, and that this power is implicated in everyday forms of social repression and in entrenching the dominant ideology. This is the ideology that reduces welfare recipients to occasional objects of pity, while systematically depriving them of any agency. Hence the outrage at the revelation that a young woman on the DPB – at a time when Māori unemployment in her age bracket was at near 40 per cent – should dare to be politically active. It is also the ideology that dictates that the lives of beneficiaries must be open to constant surveillance and monitoring, down to the most intimate details of their sexual and affective lives, and including the odious policy of ‘naming the father’.

When investigating where 23 year old Metiria Turei lived and with whom, sharing with readers partially pixelated screenshots of the Habitation Index to show just how hard they were working, journalists became indistinguishable from MSD employees or agents of the state. The very availability of that information (Audrey Young: “One of my colleagues spent several hours buried in the National Library this week trying to track down her flatmates from that time.”) became the justification for trying to uncover it. And it’s not that the political questions raised by Turei weren’t being answered at the same time, but rather that the investigation was the answer. An answer that left her exhausted, defeated and deprived of other means of describing her own life.

It all ended during Checkpoint, with John Campbell claiming that the programme had received testimonies that it simply couldn’t ignore. “We have been contacted – I guess because we ran [Mihi Forbes’ story] last night and we’ve spoken to you twice – by people saying you were getting wonderful support.” Yet at the same time as the interview was playing, one of Campbell’s producers boasted on Twitter that the information had been elicited as a result of a ‘dogged’ and very active investigation. Between those two conflicting versions of the story of how Metiria Turei was brought down lie serious questions about the social and political function of journalism: about the inevitable scrutiny that all politicians sign up to, and the freedom that still exists for individual producers and reporters to work differently, and to different ends.

...we must resist the temptation to claim that the demise of Metiria Turei was inevitable...

So what is the answer? Māori media offer both a compelling alternative model of how to investigate our political and social reality and a platform from which to critique and reorient the dominant Pākehā model. As Miriama Aoake notes, the need for Māori to establish an independent body to monitor the media – as recommended more than 10 years ago by UN Special Rapporteur Rodolfo Stavenhagen – is more urgent than ever. The whole of society, and not Māori alone, stand to gain from any reform that broadens and deepens the social responsibilities of our media. In the meantime, we must resist the temptation to claim that the demise of Metiria Turei was inevitable, that the questions had to be asked, and that once the blood was in the water the sharks must do as nature commands them.