Billy Apple®: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else

Francis Libeau on the Billy Apple retrospective currently on at Auckland Art Gallery.

Frances Duncan on the Billy Apple retrospective currently on at Auckland Art Gallery.

Black flags border the Auckland Art Gallery, each bearing the trademarked Billy Apple logo. It’s a law-suit provocation for Apple Mac if ever there was one, white on black rippling in the autumn breeze with a pirate’s warning. An old man sits as the fountain gurgles away; wearing a floppy orange shirt (made all the more orange by his amber-tone spectacles) and clutching a plastic bag, he’s muttering under his breath. No one is around. It’s Billy Apple, in his human form - elderly, tired - no doubt worn down by the install of his current retrospective ‘The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else’, his most expansive to date. If to live like everybody else is to age and exhaust, then Billy Apple, the artist, is an everyman.

Yet not every man receives a sprawling retrospective exhibition at one of the country’s major galleries. Spanning more than half a century of work, the Billy Apple retrospective ‘The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else’ is something of a takeover. Impossible to avoid, it rambles through numerous spaces, slithers billboard-scale up the gallery’s atrium wall. There are cars, crates, prints, posters, buttons, bags and boxes across paintings, sculptures and conceptual works - many of which bear, frame and support the image of the apple.

It’s the first major Billy Apple retrospective to be held in Auckland, despite it being the artist’s birthplace and home since 1990. The show brings together selections from Apple’s huge volume of work, made across more than five decades and three continents: New Zealand, England, and America. Much of it is focused on exploring, interrogating and highlighting the role of the artist and the act of practicing, exhibiting and selling art within an art market. The common thread is Billy himself.

Back in 2009, The Adam Art Gallery showed several works from Apple’s New York period 1969-1973; in the same year, a major retrospective was held at the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam. So it’s something of a belated homecoming-cum-birthday present, wrapped in a sheepishly apologetic air. This mood of cautious approval is a byproduct of the general dismissal of Billy’s work by critics on his first return to New Zealand in 1975 and again in 1979-80. Apple is aware of this; the billboard sized text sprawling the atrium wall advertises ‘The Racing Suite’ - an unrealised show he proposed as part of a long-gone Auckland Festival - with a humorously passive-aggressive hint of ‘I told you so’.

it’s something of a belated homecoming-cum-birthday present, wrapped in a sheepishly apologetic air

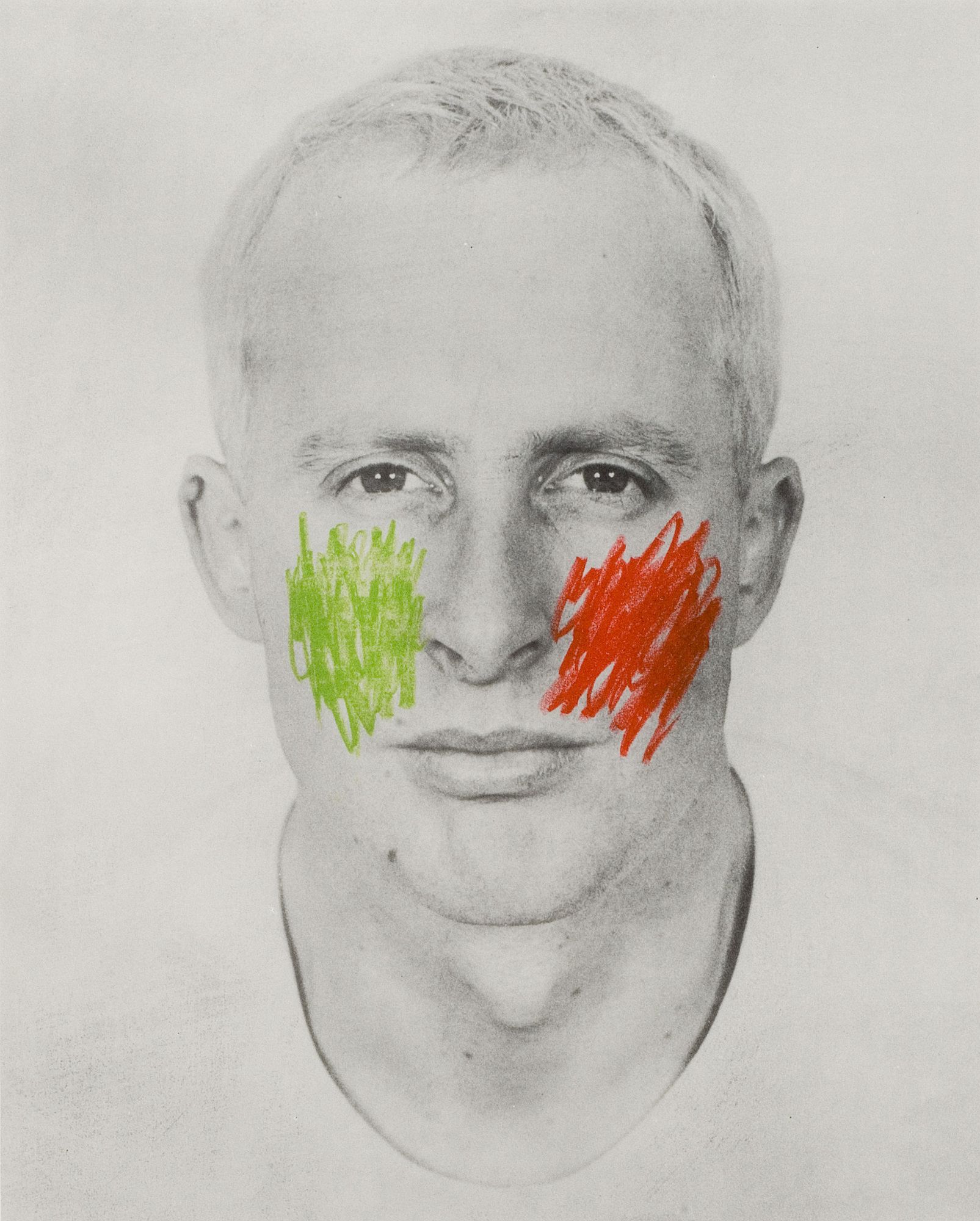

The retrospective begins suitably with the birth of Billy Apple in 1962. The math doesn’t quite stack up, the reason being that Billy Apple was actually born Barrie Bates in Auckland, 1935. The story goes: he leaves school as a teen to assist a paint manufacturer and starts to attend night classes at Elam School of Fine Arts. Catching the attention of tutor Robert Ellis, he secures a position at the Royal College of Art in London from 1959 to 1962. Upon graduation, Bates begins his work as a young artist in London, the nominative subject for exploration the one he has closest at hand - his own autobiography. Barrie Bates has got to go. The murder weapon? Clairol Crème Whip peroxide, applied liberally to both hair and eyebrows. The moment is captured on camera for RE:VISION, Billy Apple bleaching with Lady Clairol Instant Crème Whip, November 1962. It’s out of focus. Barrie changes his name along with his colouring; some time goes by and his parents back in New Zealand can’t reach him. They think he might be dead and contact the police.

The works that follow in the zone entitled ‘Young Contemporary’ explore Apple’s body as a site for art to be made: a physical entity departing from its natural form. Identity (especially in youth) is fluid, unstable and pliable; as are the modes by which the self is represented. The most potent moment of self-portraiture comes in 1962’s 2 Minutes 33 Seconds. Named for the time it took for Billy to eat an apple, three bronze casts are progressively more ‘chewed’ than the next. The apples are uncanny in their wholeness; the breakdown speaking to Billy’s attempt to renew himself against inevitable decay, as an artist and a human. It’s a neat metaphor for the artist’s desire to be immortal, and the certain failure of that desire; the apple chewed to the core, no longer shiny or fresh: when ‘Young’ and ‘Contemporary’ start to drift away from each other.

It’s also the point at which Apple’s work begins to move into the realm of the unknown and the unexpected. The confidence and thrill of youthful shape-shifting wears off and the cracks begin to show. Neon Signature (1967) backlights the apples with Billy’s name in a near indecipherable scrawl; a warped announcement of a red light district. It’s the first text-based proclamation of the Billy Apple brand, imbued with a the warm irregularity of plied neon curves.

Between 1969 and 1973, Billy ran APPLE, an alternative space in New York where artists met and showed work. In the Area of the Negative Condition is made up of conceptual pieces Apple performed in the space, looking at absence, subtraction and relief through a range of neatly-documented exercises. Black-and-white framed photographs and a series of slides show Apple in the throes of compulsive activity: cleaning one particular tile on the gallery floor; wiping one particular window pane; immaculately sweeping a square patch of roof space. These are a welcome and curious departure from his self-portraiture. They also commence a new era in which Billy Apple the artist interacts with and interrogates the shop within which the artist sells his goods: the gallery. Apple, through his ‘subtraction’ exposes the surrounds of the activity rather than drawing attention from it. Re-framed in the Auckland Art Gallery, the ‘white cube’ of the current exhibition space is highlighted, inviting a questioning of our very engagement with the documentation and re-hanging of these artworks. A bucket and cloth on the floor serve as unnecessary and somewhat gimmicky props in making this ideological leap.

During this era, some of Apple’s pieces explore his own bodily functions and fluids as the subject, with provocative intent to push the limits of acceptable artwork. A Requested Subtraction (1974) came about with the censorship of Body Activities (made up of tissues and cotton buds stained with semen, snot and ear wax) at the Serpentine Gallery in London. A gallery at the peak of its popularity, the original work shocked patrons and the gallery caved to complaints. A quick, opportunist response to the backlash showed Billy Apple at his greatest - he photographed himself removing the work, leaving the catalogue stuck to the wall with the handwritten note reading ‘A Requested Subtraction 10/4/74’. It wasn’t long before the catalogue was annotated with a brief and aggrieved message from a member of the public, now re-framed as part of the revised piece. These revisions, re-framings are what make Apple the talent he is, responding with rhizomatic fluidity to point out offenses and issues within the art world and in doing so turning things to his advantage.

Apple’s work after this period became more interested in questioning the ‘white cube’ of the gallery space, with the series entitled Censure: The Given as An Art Political Statement. They document shows where Apple interacted with structures and institutions that housed his art, questioning their neutrality through subtle alterations, obliterations and highlights. The ethos is best expressed in the 1979 show at Peter McLeavey Gallery in Wellington, on Apple’s first tour of New Zealand after leaving in 1959. He painted - in bright red - details of the gallery structure that he thought objectionable: a wooden piece of window framing. After the exhibit closed, Apple demanded that McLeavey make the proposed alterations. McLeavey didn't, instead painting the details back white. In response, Apple severed all ties with the gallery, making a pre-booked exhibition at McLeavey look unlikely - but after months of negotiations, McLeavey relented and removed several of the ten details Apple had highlighted. These were then framed as 'relics' and exhibited with companion text from Wystan Curnow, outlining the process by which they had been highlighted, removed and re-exhibited at the same gallery some two years after the initial show. Wystan Curnow’s report published in Art New Zealand 15 prior to the re-showing of the censures is telling: ‘The art space is not purified… it is revealed as being subject to, and an object of, negotiation.’

This deeply subversive series is located in the outside corridor, cut off from the natural, circular flow of the exhibit. It's easily missed. Whether a conscious choice or not, it seems an unfortunate afterthought given the subject matter of the pieces, and one I don’t entirely understand given curator Christina Barton’s dedication for Apple’s conceptual work. While the claustrophobic, long corridor serves to uncomfortably highlight the exhibition space in the way the work itself seeks to, for this to occur at the expense of people actually seeing it at all is a shame. Stunningly photographed, Apple transmutes his response to negotiations in the art world (and those of his collaborators and colleagues) into artefacts, reframing the activity and space (as he did with A Requested Subtraction) and exhibiting the results. The series loops neatly back to a quote hung on the wall alongside In the Area of Negative Condition, apparently quipped by Billy himself: ‘If you wipe a dirty spot off a wall you've removed it, but you haven't eliminated it. You're stuck with a dirty rag you didn't have before.' (Billy Apple, 1 March, 1971)

The series inspires a wish to see the concept in practice in this exhibition, through an alteration in the Auckland Art Gallery itself. The absence of Revealed-Concealed (1979) is acutely felt. When Apple applied his subtraction process to the Mackelvie Gallery, he exposed a long-concealed marble pillar and filled in a never-used recess beside the spiral staircase, installed for a cancelled commission. According to Wystan Curnow, ‘Colin McCahon found a large piece of cheap Indian muslin, dyed it red, and hung it over the recess… When finally it was taken down for a wash it shrunk up so it couldn't be used again. The wall stayed bare after that.’ It had to go. Billy filled in the hole, flushing the wall and erasing the ghost of a never-realised exhibit. Neglecting to include this work seems a massive oversight, as though the Gallery itself is self-conscious of the work being too close to home. My desire to see that which is most vigorous and questioning at work in Apple’s art is left unrealised, and I mourn the era of Billy Apple that was politically potent in its ideas and uncompromisingly cutting in execution.

I mourn the era of Billy Apple that was politically potent in its ideas and uncompromisingly cutting in execution

Curnow’s text, incorporated into the framing of Censure: The Given as An Art Political Statement is a crucial part in communicating Apple’s ideas, seeing him once again using the technical ability of others to advance his own concepts. ‘Billy Apple… put me in this position’, Curnow says knowingly. ‘What I have to say about the work is clearly my own business, but he had this idea about where I might start to say it.’ In an ongoing collaboration with Curnow, text became an increasing part of Apple’s work in the 1980s. In Auckland in 1981 Peter Webb exhibited a series of Apple paintings, each attempting to explicate their value as goods to be sold (or not, in the case of N.F.S.) and at what price (P.O.A., anyone?).

Making the social politics of the art market your subject is a brave move for any artist seeking to make a living; that Apple and Webb managed to sell the majority of the work prior to exhibition is impressive. The paintings established the stark Billy Apple painted aesthetic, employing garish, bold colours and varieties of the Futura font family, executed by signwriter Terry Maitland. The simplicity of design and clear, almost didactic nature of the text is a dramatic aesthetic shift for Apple, reclaiming the ‘art’ of painting for his own conceptual end and selling it back to actors within the art market. It’s a clever idea, but one that leaves me strangely numbed by its art market exclusivity.

‘From the Collection’ continues on in this vein, making the collectors of Billy Apple art (and the exchange of money for artwork) the very subject of it. This inspires a sense of 'value' both personal and priceless, so much so that when collector Jim Fraser’s stockpile went up for sale, the only piece that wasn't available to purchase was Billy Apple’s ‘From the Collection’. While the concept is impressive, it feels like something of an art-world circle jerk, trying to expose the structures at work within a creative community but ultimately only serving those within it.

The Billy Apple posters printed for the retrospective are more interesting. Sitting in a heap in the middle of the floor, they proclaim in his signature garish capitals: FREE FOR THE TAKING. These are, in essence, singular elements of an authentic Billy Apple work that visitors can take home with them. A man in the gallery expresses his discomfort to the gallery guide, asking if he is really allowed to walk out with it, fearing an eventual apprehension by the gallery security. The text itself posits the notion of theft, highlighting the consumer’s role in engagement with art. The fact that it is ‘free’, in spite of being a Billy Apple poster, renders it economically worthless - prodding at the ways in which art objects are valued, how and according to what drivers.

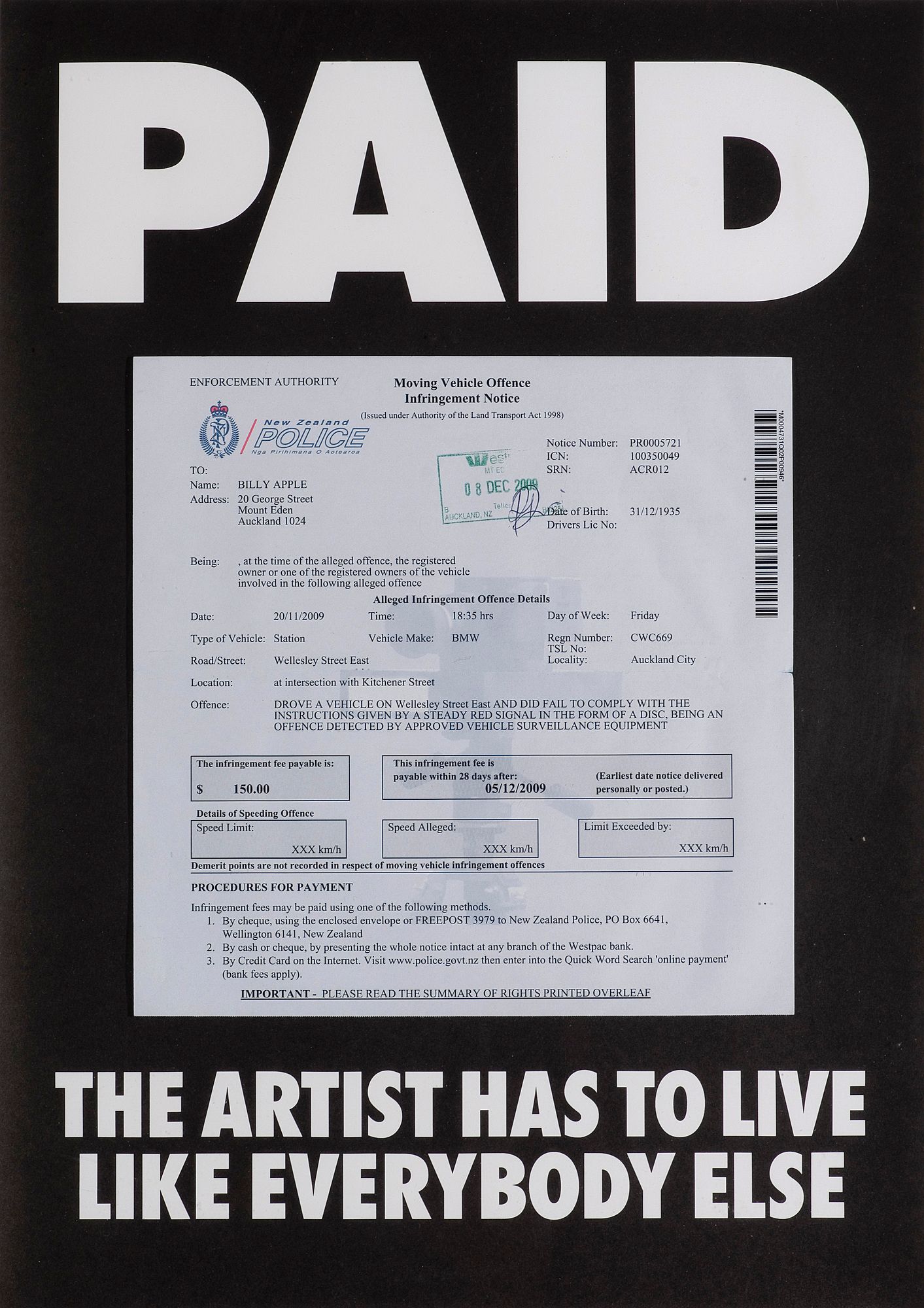

The series of ongoing works entitled ‘Paid’ emphasise the transactional through the cunning framing of receipts, invoices and IOU’s. The figure detailed on the bill was the price of the work, plus the expense of framing and the dealer’s cut. Apple’s habits (running red lights), hobbies (sports cars) and injuries (falling from a ladder) are exposed, demonstrating transparently that indeed, the artist lives like everybody else; if only in the very human sense that they make both choices and mistakes. What’s on the receipts expose something else: that beyond the mere act of transacting cash for goods, Billy Apple’s life is about as close to mine (and to the lives of most visitors to his show) as a CEO is to those who buy his company’s products. As with most of Apple’s statements, he’s more interested in provocation than truth; he’d rather start a conversation than offer some kind of succinct summation of events.

Billy has always been an ideas man. The corporatisation of the artist is an attempt at creating a self-memorialising legacy, an attempt to pass over the threshold between man and corporate entity. While his twenty-first century endeavours into trading commodities under Billy Apple® are at first glance ironically funny given the likeness of the logo to the other Apple, it’s hard for the former to connote much beyond that which the giant computer company purports. In a world saturated with branding content, Billy Apple cider, coffee and tea fall flat and uninspired. Where is the questioning, the interrogation, the anarchic tongue-poking at systematic influences that his earlier works possess? What Apple is up to now feels as comfortable as the plush leather seats in his vintage race car collection. Perhaps it could succeed if he sought to create something beyond boutique consumables for bourgeois audiences. The empty perfume bottle he designed in 1962 in the shape of a squared-off apple is endlessly more resounding in concept and aesthetic.

Where is the questioning, the interrogation, the anarchic tongue-poking at systematic influences that his earlier works possess?

The self-memorialising continues in the 2010 piece The 'Immortalisation' of Billy Apple where his DNA is literally preserved for potential cloning and genomic use. Again, in the self-proclaimed ‘Good Works’ where Apple’s paintings are sold for charity, the recipient of the donation is made the subject as with ‘From the Collection’. It’s a glib contribution to his legacy, highlighting that all things, even ideas, fall prey to death. As the body and mind decay, so does the vitality of the mind. The ironic thing is that the palpable fear of death and the desire for immortality in Apple’s later work is exactly what makes it forgettable.

So is it possible that after decades of potent, intriguing ideas, the Apple has lost its flavour? Yes, but the retrospective in itself shows that Apple is one to be remembered - even if only with a cool reverence. As he prefigured in his deteriorating bronze cast apples, nothing lasts forever. And while there may not be as much to grasp onto in his more recent work; Apple’s oeuvre is incomparable on a local scale. The retrospective indicates a deserved and well overdue acceptance of his work, a reclamation; even an apology for being a little late to the party.

Curator Barton assures that Billy Apple has had a very ‘hands-on’ approach to installation. My sighting of him looking exhausted outside the gallery indicates this to be true - a work-worn shopkeeper resting with relief after putting the final touches on what may be his biggest window display yet.

Billy Apple®: The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

14 March to 21 June 2015

Free admission