Bringing Up Bully: 'Penny Arcade' and Growing Up on the Internet

The internet's first creative boom was heralded as the revenge of the nerds - but nerds can have a lot of awful, hateful stuff pent up. Rory McKinnon on how he, and the online world, have left Penny Arcade behind.

Trigger Warning: Rape Culture, etc

WEBCOMICS are a weird breed in 2014. We live in a time where Tumblr, Twitter and Vine have reduced the technical barriers to producing visual comedy to practically zero, while a gag’s haphazard spread through aggregator sites like Buzzfeed and Reddit often leaves its creator completely unknown. But far from merely clinging on, webcomics retain a huge following: Matthew Inman’s unabashedly banal The Oatmeal rakes in some US$500,000 a year, while Cyanide & Happiness’ latest animated web series is the result of more than US$770,000 in donations hurled at the crew’s Kickstarter in a single month. Even those with ostensibly limited or “cult” followings - like the deadpan history gags of Kate Beaton’s Hark! A Vagrant or Trudy Cooper’s Oglaf [NSFW], a mashup of high fantasy tropes and sex comedy - still enjoy regular readerships reaching into the tens of thousands.

Such devoted followings aren’t simply the result of consistent production schedules: fans recognise and identify with a unique authorial voice behind the humour. They grow comfortable with the characters, the expressions, what feels like a sustained personal experience. And in some cases, like the one which finally terminated my own love affair with feminist-baiting chauvinists Penny Arcade, that first Internet Famous generation is now struggling to adapt to an online environment that treats them as regular users whose work is open to critique, rather than some special tier of minor celebrity.

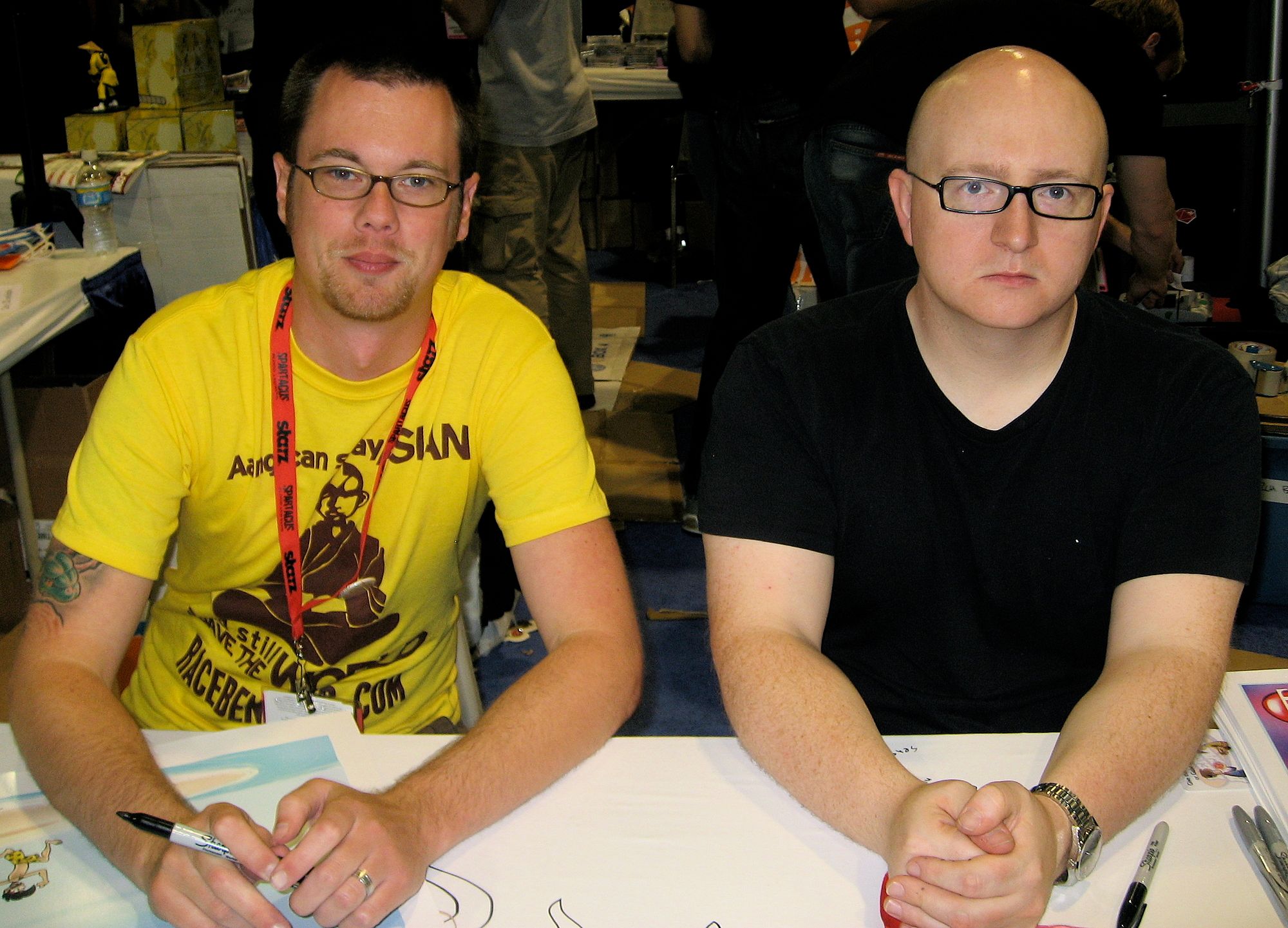

Launched way back in 1998 - the Jurassic in online terms – Penny Arcade was very nearly the first webcomic, period. These days the premise of 'two guys talking about videogames' is so ubiquitous that even parodies of knock-offs have their own fan followings. But when I stumbled upon it at age fourteen, Penny Arcade's combination of acerbic takedowns and relentless interrogation of the absurdity of videogame logic felt like a perfect reflection of the sniggering, arch conversations that flashed back and forth in my own nerdy social circle. Not least because the whole undertaking was a conversation: its dialogue was typically culled from actual conversations between its writer Jerry Holkins and illustrator Mike Krahulik, while blog posts appearing throughout the week carried on the repartee for readers' amusement. Official messageboards and a smattering of unofficial fansites meanwhile invited readers to emulate Krahulik and Holkins with our best one-liners, but more importantly they offered a kind of sanctuary: where the Internet as a whole in that era thrived on anonymity, forums invited you to acquire a reputation as a wit while concealing all of the embarassments and personal history that friends at school were merely gracious enough to overlook. And of course, it was somewhere to riff on clever observations like the Fuckwad Theory.

Gabriel's Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory is one of Penny Arcade’s more positive contributions to public discourse, pithily expressed as “Normal person + Audience + Anonymity = Total Fuckwad”. More recently, Holkins introduced the corollary that a normal person with an audience minus consequences could also become a total fuckwad: a formula that could readily apply to, say, two millionaires with a vast fanbase willing to absolve its idols of anything.

I mention all this because Holkins’ co-creator Mike Krahulik has been in an apologetic mood: in January he vaguely alluded to various terrible things he said last year in a post called “Resolutions”:

As a young person I imagined myself a sort of vengeful spirit. A schoolyard Robin Hood who attacked the strong and popular on behalf of the social outcasts. I’m 36 years old now though and I realize what I am is a bully. I may have been the one who got beat up but I sent plenty of kids home in tears. I also realize that I carried those ridiculous insecurities into adulthood. I still see people who attack me as the enemy and I strike back with the same ferocity as that seventh grader I used to be. I’m ashamed of that and embarrassed.

Krahulik has written about his anger management issues before, and ironically it was his work that allowed me to break out of that cycle myself: as a gawky, geeky fourteen-year-old in yet another new school I could have easily re-established a reputation for being a seething ball of rage, too volatile to resist prodding. But the new crew of nerds that I found myself with were all giggling at catchphrases from this cartoon thing over handball, and before long I was hooked too: not just on the surreal humour or the profanity-laden comebacks, but the hope their the creators’ success afforded that you will come out of this okay, with close friendships, a comfortable living and meaningful creative work.

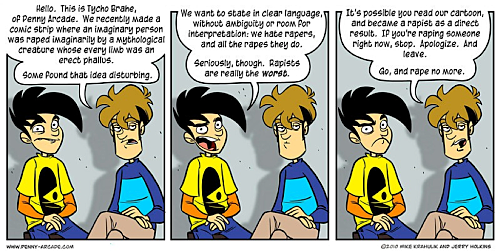

It’s a shame then that a creative duo which gave me such hope for my future could be so callous and vindictive to others with far harder stories, and unfortunately I don’t buy Krahulik’s latest mea culpa either. It’s to be assumed that he’s referring at least in part to his comments in September reigniting the ‘Dickwolves’ controversy: a mean-spirited affair stemming from a 2010 strip in which rape by imagined “dickwolves” served as the setup to a punchline about videogame quest rewards.

Feminist blogger Shakesville’s initial response remains an excellent summary and critique of the strip itself, but it all went supernova when Krahulik and Holkins sought to dismiss the reaction with a snarky PSA and a month later began selling sports team-themed “Dickwolves” merchandise. The most virulently misogynistic fans, who had taken to haranguing dissenters with slurs and sexual threats, took this as Penny Arcade’s seal of approval and began proudly toting the gear at meet-ups and conventions under the banner of “Team Rape”. Believe it or not, the Penny Arcade crew went on to escalate things still further, but for that I’d refer you to the exhaustive blow-by-blow timeline at Debacle.

So far, so awful, so which brings us to Krahulik’s apology. But here’s the thing: where Krahulik draws attention exclusively to his anger management issues, I would suggest that this is primarily a case study of he and Holkins’ own Internet Fuckwad Theory — and with an important lesson for those creative types who find themselves now contending with a new iteration of the internet.

*

Penny Arcade began in 1998 with two guys, a regular spot on the now-defunct LoonyGames.com and a monthly tipjar. Sixteen years on it's now a sprawling multi-million dollar empire encompassing annual gaming expos on two continents, a line of designer menswear, reality TV shows, a series of their own licensed games, collectibles and the usual raft of anthologies and merchandise. The fanbase has swelled to some 3.5 million, but the strip’s sensibilities haven’t changed in the slightest, and seemingly neither has its demographic (average age 26, 94 percent male, average household income US$60,000, according to a 2009 survey).

What has changed is its creators’ position: instead of caustic twenty-somethings languishing in relative anonymity, it’s now helmed by industry tastemakers who are now pushing forty, so flush with merchandise sales and donations that they actively eschew advertisers, and who can rely on a volunteer army to swamp any and all criticism; an office of Paypal infallibility.

Krahulik and Holkins are not angry young outcasts: in fact the exact conditions of last year’s blowout are testament to that, with the exact moment caught right here on video. At the fan convention PAX 2013, in a panel dedicated exclusively to Gabe and Tycho's work and attended by three thousand of their most hardcore fans, the pair were quizzed by their friend and business partner Robert Khoo, in: the ultimate soft-ball interview.

The footage itself is simultaneously cosy and cringeworthy. Robert asks if there was anything he had handled on the business side of Penny Arcade that they would have done differently — an open-ended question with no mention whatsoever of the 2010 controversy.

Mike pauses before deciding, entirely unprompted, to make a categorical statement on the affair:

"I think that pulling the Dickwolves merchandise was a mistake."

A wave of raw-throated cheers erupts from the crowd, which he receives in silence. This is not one of the low blows that Krahulik talks about in his New Year’s Resolutions, a crazed lashing out from someone backed into a corner. This is a cool, collected statement from someone in an environment of total adulation. Smithers-like, Khoo unsurprisingly agrees with his boss, describing the decision to get rid of the gear as “a way of engaging” and thereby encouraging a backlash.

To date Krahulik has never expanded on this; never publicly explained why he wanted to keep selling the shirts over and above the protestations of rape survivors. His latest resolutions do not account for this entirely different mode of behaviour: far from being overly defensive, this was a man reveling in his ability to say anything and be adored for it.

It’s been said of all this that Penny Arcade has a “Krahulik problem”. But speaking as a fan of the series almost since its inception, I don’t think that’s true. What it has is a Holkins/Krahulik problem, in that both creators have refused to acknowledge that recent cultural and technological shifts have radically altered the dynamic between fans, creators and critics.

It's mind-numbingly obvious to say that fourteen years ago, pop culture critics like Jezebel or Colorlines didn't exist (Gail Simone's Women In Refrigerators, a running tally of women maimed, killed or otherwise traumatised in comic books, being one of the few exceptions). But more significantly, pop culture sites didn't exist: not the broad-brush aggregators we have today, anyway. If you were curious about the casting in the next Lord Of The Rings movie, you had to trawl through webrings of poorly-maintained personal fanpages or register for the forums on TheOneRing.net. If you took issue with Limp Bizkit's lyrical content, your only options online were the message-in-a-bottle that was a Xanga post, or the unlikely prospect of a fan forum or IRC channel. Even a forum or IRC channel meant contending not just with others' opinions, but volunteer moderators (hardcore fans by definition) who could all too often delete your carefully-constructed critique and ban you on grounds of 'flaming' (starting an argument simply to stir up trouble).

The end result was that only the most die-hard fans found themselves in a position to discuss the material with others, and that naturally tends towards unconditional praise. And Penny Arcade was no different.

I remember the fanbase of the early years, so cloistered that we jokingly referred to ourselves as “the cult”. We were a close-knit community of smart-arses in our teens or early 20s, mostly young men, with one-liners and one-upmanship ingrained by the Penny Arcade ethos as much as anything else. As with so many straight, white, males, Penny Arcade pushed the philosophy that nothing was off-limits, however outlandish or taboo, so long as it was framed as a joke.

We loved the comic for its finely-tuned sense of the absurd: in one strip, a gauche young space frog confides in a mentor about his budding sexuality; in another, a Greek warrior daubed with his murdered family’s ashes takes a course in art therapy.

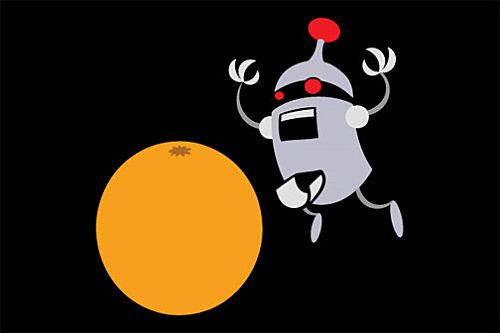

But the rape jokes were already there, and in retrospect it’s clear that an outcry over something like Dickwolves was simply a matter of time and exposure. Back then such reactions were confined to obscure members-only fan forums and dissent was easily corralled and buried beneath a morass of new discussion threads. But I can only imagine how the Fruit Fucker 2000 would go down on Twitter and Tumblr today.

The Fruit Fucker is one of the series’ most iconic characters and still sporadically features in strips today as an in-joke for the older crowd. First appearing in 2002, the anthropomorphic electric juicer - replete with the tagline, “Make fruit your bitch” - is objectively one of the shallowest gags imaginable. It rapes pieces of fruit with a little mechanical penis and then cums in a glass. It’s funny because fruit can’t give consent, therefore it’s rape. That’s the joke, and the character’s existence, in its entirety.

It’s worth noting that Krahulik still considers the Fruit Fucker among his favourites, and the act of rape is explicitly the foundation of its humour. I can recall how the ad copy for a now discontinued line of Fruit Fucker T-shirts described “a used and dejected orange” on the back. Meanwhile the site’s archives still hold a particularly disturbing strip in which it’s heavily implied that the Fruit Fucker sexually assaulted a fictionalised version of Holkins’ then-girlfriend in her sleep.

{Kara and Brenna are sat at a table facing each other. They both have cups of coffee.}

Kara: I don't know why they keep that little freak around.

Brenna: You know I caught him touching my hair once, when I was asleep?

{Scene change. Brenna is in her bed, terrified, as the Fruit Fucker fondles her hair.}

{Back to Kara and Brenna. Kara has put her hand on Brenna's shoulder as she sheds a tear.}

Kara: I'm so sorry.

Brenna: {crying} I used an entire box of Q-tips.

I was enough of an idiot kid at the time to find this kind of daring high-concept stuff hilarious, despite growing up the only male in a house full of women. These were hardly unique sentiments - you can find similar punchlines today in the cesspools of 4chan, Reddit and Something Awful - but Holkins’ expansive vocabulary lent the whole thing a veneer of wit that proved fatal to sixteen-year-old boys with literary pretensions: the more obscene and vulgar something was, the funnier you were for saying it.

I’m ashamed to say it took a long time to shake off, too: at 20 I was still the kind of obnoxious creep at the student magazine to print LOLcat memes about rape and shoehorn the phrase ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ into coverage of a lecturers’ union dispute. By Christ I hope I’ve changed, but that’s who I was: the edgy humorist with no victims, only prudes. This, Penny Arcade had taught me, was the high road to glory.

A decade on, it’s that same miserable appeal to artistic integrity which continues to dominate Penny Arcade’s response to the Dickwolves affair. The difference is that the proliferation of wireless technology, social networking sites and the app has not just extended internet access to a more diverse range of people, but made it far easier to take a casual interest in any given facet of pop culture: hashtags and pop culture blogs represent hubs for people with shared experiences to band together and discuss the politics of everything from JJ Abrams' Star Trek to Lena Dunham's Girls, while a platform like Twitter allows dissenting voices to air their criticisms on an equal footing, without fear of bans or deletion.

So Penny Arcade, for all its millions of fans, is a microcosm; a tiny rockpool in this turning tide. Just as transphobic newspaper columnists bemoan “the Twitter mob”, longing for the days when they could simply assume most readers nodded sagely over their morning coffee, so too has Penny Arcade insisted that their work remains a walled garden, exempt from a technological and cultural shift that has encouraged immediate feedback and a societal discourse about sex and gender and power dynamics. As Holkins himself puts it, he is “not entirely certain that a conversation is possible”.

The perspectives in play, the lenses, are too different: one side believes that not according the issue of rape the proper respect fuels a kind of perverse, perpetual engine called rape culture. There is a vast, specific lexicon and hundreds of tacit assumptions that gird it. The other side (that’s me, but not just me) believes that when it comes to expression nothing is off the table. It is the creator’s prerogative to create something - even something grotesque - out of anything they can find.

Essentially Penny Arcade represents an old guard of artists, authors, musicians, game designers and other creative types who have jealously guarded their “edgy” independent streak — only to find themselves now unable to engage with those who want to talk meaningfully about their work.

It's instructive to compare and contrast the Penny Arcade team's attitude to criticism with that of their friend and fellow webcomic artist Kris Straub. To date Straub has made no public comment on Penny Arcade's troubles. But in March Straub did respond to a bizarre polemic against “#hate” making its way around the webcomics community, courtesy of Zen Pencils illustrator Gavin Aung Than. As Straub put it:

i have always thought negativity was allowed to be part of the conversation — depending on how it’s expressed. this is why i love parody and satire. good satire destroys its target from within — and the only way it got inside is because its originator loved the thing they took apart. it demands self-reflection, which is always useful. no one is immune to it. and something stronger and more bulletproof can emerge.

it’s too easy to discount detractors as haters, or just jealous. it is really, really hard to read negative comments. a single one can obliterate 100 positive ones. but amid the hate, maybe someone has a good point. you have to wade through it from time to time. it can make you miserable — but it can also keep you humble.

Humbling it may be, but surely there's also something implicitly exciting about this era of mass exposure. We share and interrogate these works with hardcore fans and strangers alike; discussions that can introduce a beardy white manchild like me to brilliant thinkers like Mattie Brice. Sure, everyone’s a critic, but that’s far more stimulating than the previous decade's ghettos of slavish devotion. The revenge of the nerds has been and gone, and the increased scrutiny that webcomics and geek culture are now experiencing is arguably itself a mark of maturity for the art form. That's to be welcomed. After all, if there’s anyone who should understand the perils of perpetual adolescence, it’s Holkins and Krahulik.