Caucasian Fir

On a road trip down South, Emma Blackett sees the roots of colonialism in Aotearoa, and the ghosts of those forgotten.

Please note: this essay discusses sexual abuse

What were these mysteries?

Was there only one world after all, which spent its time dreaming of others?

— Philip Pullman, The Subtle Knife

“He lives in ‘beautiful tow-ronga’ because Howick now is too full of – yi’know – foreigners.”

“Oh, he was that bad?”

“Yeah, so he definitely didn’t understand when I replied, ‘some more recent arrivals, maybe’ – he went quiet for a while. You can’t keep a man like that from telling you his life story, though. He’s a chemical engineer, has a sister in Cromwell, and a 16-year-old ‘darling granddaughter’ who loves media studies; his wife went to university too, once, ‘like you,’ he said, ‘back in the day where we all got scholarships and a degree was something to really be proud of’; he’ll never go back to Auckland but has been here, to Queenstown, many times, and he’s on his way to Stewart Island now for a holiday. He doesn’t know anything about me except from me telling him I’m doing a PhD, because for some dumb reason I always try to make men like that think I’m serious.”

“How can someone have the confidence to talk so much about himself?”

“Well, for starters you’re a person who takes more than the whole armrest. Men almost always do that, though. As we landed he leaned across me to look out the window and said, ‘Ah, the Remarkables! Aren’t they just?’”

*

You and I drive away from Queenstown, take pit-stops, drive, talk about the drama in the land, all serrated edges and ice-blue water. The absence of recognisably native bush or te reo place-names comes up too, as we mock the tourist architecture in Arrowtown and ‘Old Cromwell’. Kitsch monuments to the gold rush line each main street: low roofs with colonial signs – post offices, banks, a few ‘royal’ hotels.

Visitors to Arrowtown can pan for gold in a trough full of wet pebbles outside a ‘Chinese miner settlement’, or pose for souvenir photos in Victorian frocks. A hitching post for ghost horses marks the entrance to Old Cromwell. Both places are cutesy, less desert-roughened versions of the ‘Wild West’ re-enactment towns in the US–Mexico borderlands that novelist Valeria Luiselli writes about, where, as Gloria Anzaldúa says in Borderlands/La Frontera, “the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.” In an essay called ‘Letters from Tombstone’, Luiselli says that “Tombstone [Arizona] is a ghost of a ghost town …. A kind of Hades, ruled by the law of eternal return. It was a space where the past had been replaced by a peculiar, repetitive, and selective representation of the past.”

What is it like to live ‘distrusted’ and then to die only to be laid outside settlement walls[…]?

After Cromwell (the town) we talk about Cromwell (Oliver) – I say he was the first fascist, destroyer of others’ idols. You say that Naseby, our destination, was named after a battle he fought in. I think of Lyra in Philip Pullman’s The Subtle Knife, a girl shocked to find hard pieces of her world in another universe where they do not belong; of the multiverse of cultural difference, crushed by imperialism but not erased; of the white world, taking and taking, only to build kit-set shrines to its own crimes.

After Clyde we pass yellow grasses and moon-like rockscapes, all windswept and desperately dry. Unexpectedly, I recognise the rocks.

At 17 I had just told everyone I was a lesbian and then got in a car to drive south for the summer with my friend Nick. I fell in love at a New Year festival. Through hot days in Nick’s passenger seat, I dreamed of the festival girl (of her and me pressing our palms together and holding them up to torchlight at 3am, admiring how exactly our fingers were the same length). Nick, a sullen ally by day, would touch me as I slept, tracking criminally far beyond any sort of alliance.

“I think I’ve been here before, with Nick,” I say to you. “Trying not to think about it. And maybe I’m wrong, maybe it just looks similar.”

“Yeah,” you say, in a jokey voice that shakes a bit too much to be funny. “You know, you probably would have stayed on State Highway 8, but this, this is 85.”

We pull over by a river and try to nap on the tray of your filmboy ute, but I’m restless, a bit numb, still haven’t closed the gap between me and you. I kiss you until we both breathe heavily enough to become too aware of other people downstream. We keep driving.

As I explain Greta Gerwig’s Little Women to you, we come to a bridge I know. I’d gone to uni by 17 but still used my school darkroom to develop and print photos. Hidden in a biscuit tin at home is an inky, crooked-edged image of this bridge and its woven streams. Crossing with you, I remember Nick and I sleeping underneath, down by the water, raw skins hiding from the sun.

I think of Caucasian firs; planted in the early days of colonisation, but still growing.

Alison Maclean’s 1992 film Crush opens with a car crash. Two Pākehā women, Christina and Lane, are driving to Rotorua. Christina describes this country to Lane, a newer visitor: “No predators, no poisonous spiders, no snakes. New Zealand’s this totally benign, paradisiacal, prelapsarian world, and we’re uneasy about it …. There’s this obsession to uncover the germ of evil, search for the snake.” She concludes, seeming to address me, that “we have a streak of perversity.” The perverse drama of Crush crashes in then because just as Christina says “perversity”, Lane is distracted from driving by a buxom blonde mannequin, stood crookedly by a sharp bend in the road. The women’s red hatchback veers over the verge and somersaults down a slope, every crushing impact made heavier with the violence of slow motion.

Waste product of the fashion industry, lost object in the global commerce of sex images, plastic and hollow and, like Christina and Lane, not belonging to this place but not properly from anywhere else, the mannequin is a warning about the way things appear. In one reading, the crash is absurd. Stripped of whatever its original purpose, the mannequin is set there, simply, cruelly, to mean nothing (it is – absurdly, and you have to pause at exactly the right moment to catch this – advertising “organic vegetables”). For me, the mannequin is an uncanny representation of ‘national beauty’, an ugliness borne of beauty gone fatally wrong. It’s a better image of ‘New Zealand’ than the deep-green vistas this country builds its identity around.

Blinking away flashes of carnage – the red car crunch-tumbling off the road, Lane’s red leather jacket floating at the bottom of the Huka Falls, flashes of that being us – I ask you to talk.

*

We arrive at your Naseby sleepout. Yellow chip-board walls, unclaimed bunk beds, utilitarian carpet on a concrete floor. I move over you, trying to leave this ‘me’ for an unfractured ‘us’, as though sex could do that. You respond quickly from a month of nothing. And I’m there, I was there, but as soon as you break a sweat my heat dissipates. You reach to touch me but I draw your hands away, saying gently that it’s okay, “I think I lost it.”

“Oh, are you alright?”

“Mhmm.”

I nod, smile, then suddenly stop smiling and turn sharply to the ceiling, winded by fury. It’s a new injury, another one, a cruelty doubling down like the very sickest of jokes, to remember him when I want to be with you. That night a fire alarm sounds across the town, a low swelling howl like if sirens cried so loud, banshees of the water, calling warnings to men at sea. I look out at the street. Nothing moves, and there are no other sounds.

*

The next day I take a while to venture out, shifting between books and essays and old notes, trying to write something ‘thesis’. By 4pm the day’s heat has arrived, the café’s closed, the pub’s open, and I’ve walked one slow lap of town, spooked by how haunted its settler relics feel, with no people around to remind me of the present as I think I know it. An old cobbler’s, a newspaper house, two hotels, a post office, a council building, even a Masonic hall – all have freshly painted 19th-century facades. Diminutive doorways remind me how undernourished colonists were. One of the hotels has burnt down but its shell remains. The other is the only place open on this Monday afternoon.I see one person: a pink-faced man outside a shop, leaning on a grey-blue 1960s sedan. He waves stiffly at me. The small shop looks like it’s been out of action for years, the car long stilled, the man tired. I turn away, skittish.

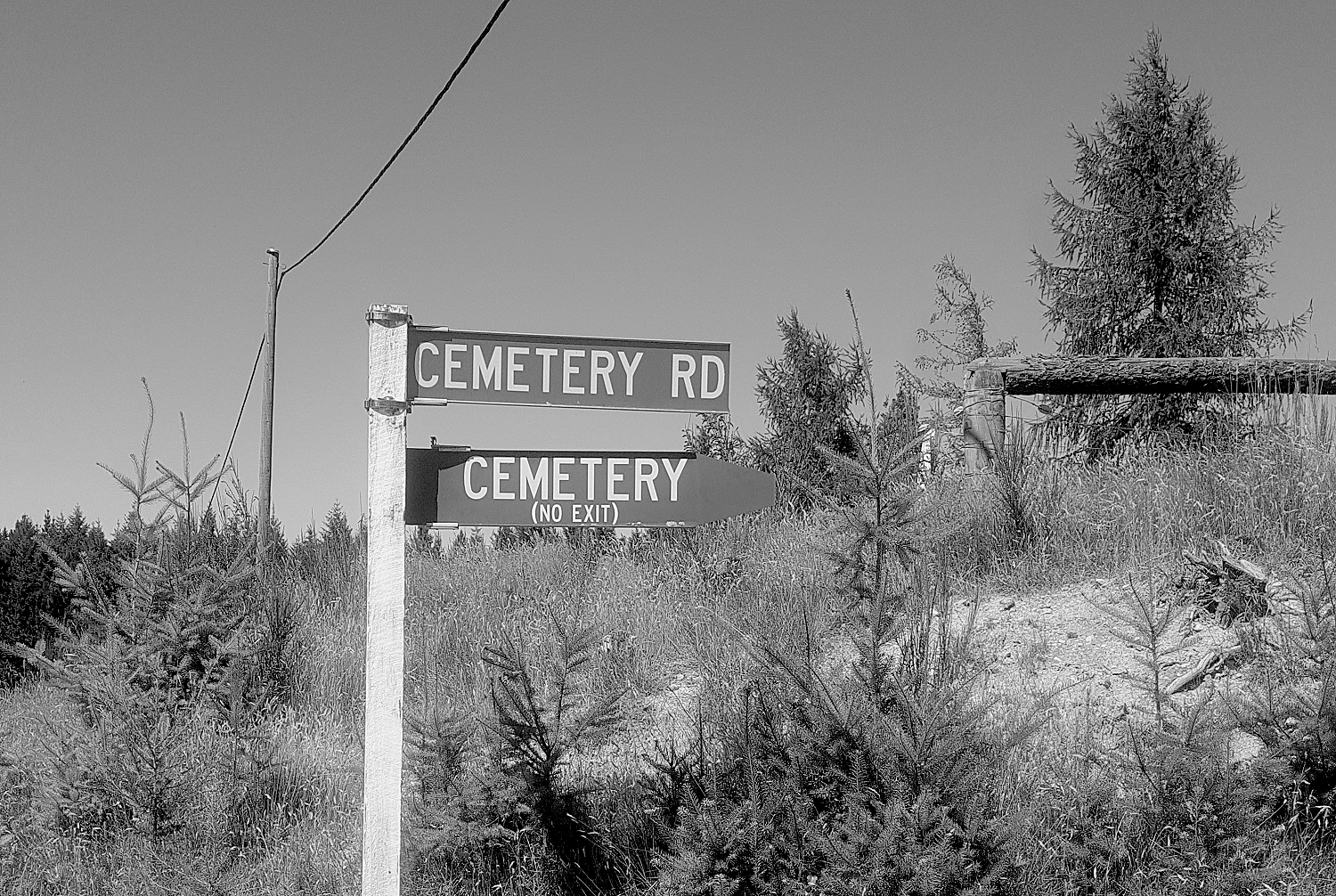

To be queer is to stray from straight, to cut through life on a curly slant.

In May 1863 someone found gold in Maniototo and men rushed in, founded this town, gave it its military name, and housed 4000 newcomers within six months of turning the first shiny dust. A decade saw the building of many hotels, a courthouse, a hospital, a curling rink, three churches and a large graveyard. Naseby was set to become the regional hub but then railway construction was diverted away in 1898, seeding Ranfurly, which quickly became bigger (and is still busy by comparison). Naseby was left just as Valeria Luiselli describes Tombstone, another mining town that went bust in the 1890s and was abandoned, “only to enter a strange kind of afterlife.”What does this similarity mean, these twin trans-Pacific ghosts of ghost towns?A tautology is a haunted form – two parallel mirrors facing inward, reflecting reflections into infinity.A park, fenced by grand European trees, marks the middle of town. Its stone toilet block sends “Ladies” left and “Men” right. I stalk diagonally across the grass.*The film you’re working on shoots at dusk so each day you start in the late morning, but after we wake you fill the time busying yourself, like it’s a bit too hard to look at me.On Tuesday I decide to find the graveyard. A tourist pamphlet says it’ll be at the end of Cemetery Road. Easy. “NO EXIT”, the street sign says. I walk for a while on Cemetery Road, a gravel track that leads away from the houses, up a hill of scraggy pine forest. It’s too far from the buildings to be the right place, and much too Twin Peaks for comfort, but trees along the way seem planted to form – if the town had kept up, the branches pruned – something like an avenue, a road framed and shaded by great trees.The cemetery appears, at the crest of the hill. Gravestones are clustered mostly off to the western side of a broad, groomed clearing, edged by more tall pines (rolling hills visible between them, no sign of the town). A low fence separates the road from the graves. A sign next to the entrance gate explains that Protestants are buried to my left, Catholics to my right, and also to the right are the graves of Chinese miners, “outside the cemetery wall, where the ornamental trees stand.”“The Chinese population was initially distrusted by the largely European community,” the sign continues, “but was later well accepted.” (“Howick now is too full of – yi’know – foreigners.”)A few tended shrubs are spaced neatly to the right, on the outside of the area designated for burials, just as the sign says, but no graves are visible there. I wonder where they’ve gone, why they’ve left no trace.Ghosts matter, they matter immensely. Ghosts matter because, as Anne McClintock writes in an essay called ‘Imperial Ghosting’1, they “are fetishes of the in-between, marking places of irresolution, particularly in the adjudication of property, territory, power and justice.” For Eve Tuck and C. Ree, who speak with the singular voice of an anticolonial revenant (“I don’t want to hurt you, but I will”), imperial ghosts are “spectres that collapse time, rendering empire’s foundational past impossible to erase from the national present.”I read again, aloud: “outside the cemetery wall, where the ornamental trees stand.”The sign goes on to explain that Chinese remains in this area were exhumed at the turn of the 20th century for return to China – “their souls would not rest easily unless returned home” – but their carriage, the SS Ventnor, was wrecked off the coast of Hokianga.UntitledWhat is it like to live ‘distrusted’ and then to die only to be laid outside settlement walls, never settling, your gravestone discarded later by those who willed you home, only – crash – to meet waves?Nearly all the Christians in the Naseby graveyard died before 1900 but, strangely, new flowers adorn many of their tombstones.I walk from the Protestants on the western half – wondering about a 19-year-old woman, unmarried, buried with her five-year-old daughter and a baby – through the Catholic half, and over 50 paces of empty space to the trees on the eastern edge, where I might be able to see Naseby.There they are: six or seven headstones bearing Chinese names, epitaphs facing away from all the others. They’re much too close to the trees, much too close to the rough fence just outside the trees, the space each body deserves written through by a wall of wire and wood. One of the pines, grown enough now that it would take two of me to reach around it and meet hands, is planted directly on top of a gravesite.I scratch its bark, study it, this parasite. Not a standard pine tree. Its foliage is fuller, bluer, hangs with a sort of grace, and the cones littering the ground are tight like nutty grenades.As I re-enter town I see the same trees everywhere, understanding now what “ornamental” means. They aren’t delicate or small, as I’d first guessed, but they are decorative, or better declarative: stakes planted by those who claim to own this place, to designate both its character and its borders.A main-street villa has a clutch of these trees in its front garden. One is labelled with a neat plaque: “CAUCASIAN FIR”.*On Wednesday my brilliant friend Anisha Sankar sends me an essay she’s just had published, about rising fascism in India, its colonial origins, and her relationship to that past-now-present, as a Chennai-born kid raised in Aotearoa. She writes about the politics of roots:

“The errant, writes Glissant [Édouard, Carribean poet and scholar], lacks a ‘totalitarian root’ – a root which takes stock all upon itself and kills everything around it. This kind of totalitarian root is what Western civilisations are founded on, claiming a dominant and static relationship to land and others.”

I think of Caucasian firs; planted in the early days of colonisation, but still growing; trunks shooting straight up and down, horizontal branches spreading up the central post like sharp biblical stars. In the Naseby cemetery, lines of these trees stake totalitarian claims as they insulate inside from outside, inclusion from exclusion, ownership from dispossession.“Instead,” Anisha continues, Glissant “imagines the errant as having ‘rhizomatic roots’ – a system of roots, entangled and enmeshed, spreading through ground and air … open, mobile, and constantly in motion.”I walk around town more, wending through each street with no ambition other than to look. At the end of another dead-end road, a beige warehouse next to an old curling rink contains a new curling rink. The original is just a dirt oval framed by rusty bleachers. Across the road, in the corner of a brown paddock, a tin shed bears the hand-painted sign “SKATES FOR HIRE”.On the other side of town, I try to go into the woods where there’s a network of walking tracks, but the tourist map at the mouth of the tracks tells me “You Are Here”, in the middle of a red-coloured region dubbed “Badlands”.I wish the Badlands didn’t scare me, because errant figures are also disobedient – to err is to be wrong, and rebels are always wrong in the eyes of big power, like Donna Haraway’s fuck-the-system-that-spawned-you heroines in The Cyborg Manifesto. “The main trouble with them, of course, is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism. But illegitimate offspring are often exceedingly unfaithful to their origins. Their fathers, after all, are inessential.”To be errant is to roam (not to be lost), to err (but not to be wrong at all, in just terms) from establishment paths, roving, often exiled from where you began. This creative way-making could also be called ‘queer’, a word that once meant twisting or crooked. To be queer is to stray from straight, to cut through life on a curly slant.*After dodging the Badlands I go to the pub, ask for whiskey, unsure where to place my rage. “Cultural residues piled up so high the present reels.”A rough voice holds forth behind me, crass Pākehā vowels, slurred ‘r’s.“Heh- Heh- Heehkia Parah-ta.”“Sexy one, huh?” says another man.“Yehp, attractive girl, yup. John Key was shaggin ‘er and – ah – Bronwyn, Bronwyn wasn’t happy –”“Bronagh,” says a woman.“Bronagh wasn’t happy so he covered it up and left, yeah. That’s how we got Jacinda.” default1 Anne McClintock. (2014). Imperial Ghosting and National Tragedy: Revenants from Hiroshima and Indian Country in the War on Terror. PMLA 129(4): 819-829.