Welcoming Internationality: In Conversation with Artspace’s Incoming and Outgoing Directors

Visual Arts Editor Lana Lopesi talks architecture, safe spaces and the ‘international’, with Misal Adnan Yıldız and Remco de Blaaij.

Visual Arts Editor Lana Lopesi talks architecture, safe spaces and the ‘international’, with Misal Adnan Yıldız and Remco de Blaaij.

I am not alone in my fascination with Artspace’s directorship. Within a short tenure of only three years, each director carries the burden of having to both stimulate and antagonise the national art community. Artspace itself faces perceptions of exclusivity and nepotism, yet it has also proved to be a space of experimentation and dynamism.

Misal Adnan Yıldız has been at the helm of Artspace for the last 2.5 years and is now getting ready to leave Moananui-a-kiwa for Berlin once again. During his tenure, Yıldız was not only responsible for the significant architectural changes of the gallery – literally opening up the space – but he also developed a complex programme in and outside of the gallery which elegantly combined the art riff-raff with the art darlings.

Last year, Yıldız trolled me on Facebook after a review of the exhibition New Perspectives, although he recently confided in me that he had “learnt his lesson”. While it was difficult in that instance for me to appreciate, it was that exact passionate and personal attachment to his own exhibition-making practice and the artists he works with that has underpinned his Auckland programme. The persistence of Yıldız’s long and meaningful engagements has meant we have been a very privileged audience.

On 18 May 2017, three new solo exhibitions under the umbrella of Singular Pluralities ∞ Plural Singularities opened, marking Yıldız’s last exhibition and turning the conversation toward Artspace’s next Director, Remco de Blaaij. De Blaaij joins Artspace on the gallery’s thirtieth anniversary. Currently the Senior Curator at the Centre of Contemporary Arts in Glasgow, de Blaaij, is relocating to Aotearoa with his partner and three children in August.

On a brisk autumn morning, I walked into Artspace to meet Misal Adnan Yıldız and Remco de Blaaij. They were huddled in Adnan’s near-empty work space talking about the practical things, like desks. I led them next door into the Tautai Contemporary Pacific Arts Trust meeting room. De Blaaij poured three glasses of water from the water cooler and we sat down.

Lana Lopesi: So, congratulations [gestures to toward de Blaaij]. Artspace is a very special institution for us here, we watch it very closely and as you know it has a strange position as being independent but publicly funded, but also has more freedom then the big institutions like the ones down the road. So Remco, I want to start by asking you, why Artspace?

Remco de Blaaij: As opposed to something else, right? I don’t think it can sit on its own. If you say why Artspace you also have to then know what would be the alternatives, no? Much of it is just a feeling I guess. When you apply for a job, or a project, it’s not a completely calculated decision, as much of it is also about a feeling. So, much of it is a mystery to me as well. I tend to work a bit like this which is why I left the Netherlands because it is such a calculated, European way of working that I think is going to get us into trouble in the next 10 or 20 years.

On the other hand, of course, I have been following the Artspace programme. Also, New Zealand as a country and as a social geography was interesting for me. We [the world] are in a big mess socially and politically, and New Zealand seems to be close to those kinds of things in terms of politics and historically it has the connection to the UK and of course this colonial relationship. And [yet] it is out of Europe, it is completely different, everything is flipped, no? Like the time is different for me, and the weather is the opposite of mine and so you would kind of expect that there is also a total opposite of ideas, so that excites me a lot.

I really believe that there is a huge potential for small art spaces. They are much more flexible in order respond to things. Now in Europe and I guess here as well, there has been 20, 30 years of people wanting to build new spaces and to have “more, more!” – constantly more and newer or whatever. If you look at Tate, for example, maybe the most iconic example of that, they just built a multi-million-dollar new wing and it is not about content or about ideas, it is just about shifting money. It’s kind of a money-making thing in its own right you know? So, that’s why these wings can exist. But then, the collection will still not completely be on display and the things that will be happening in there will be the same.

So, I think Artspace, seems to me – which is of course a bit of speculation – exactly this smaller, interesting space that can be very flexible. I feel that there is a potential in that. And if tomorrow it decides not to be Artspace, but more of a socially committed space, or something else if the city needs it, then it can do it, no?

And if tomorrow it decides not to be Artspace, but more of a socially committed space, or something else if the city needs it, then it can do it, no?

LL: And so now that you are leaving Adnan, is there anything in what Remco has said that reminds you of yourself 2.5 years ago, when you were getting ready to start the job?

Misal Adnan Yıldız: Remco sounds much more interested in the opportunity within the social political context. I was interested in the same issues too, but I came here also with a personal crisis. Like I am not from Europe, but I have lived in Europe for many years and I wanted to experience a different context, somewhere else. I am someone that never did this gap year or “overseas experience” kind of thing, so we, [my colleague] Leah [and I], sometimes make these jokes like this was my overseas experience.

[everyone laughs]

But I agree with Remco, about the flexibility of the scale of an institution and sometimes from outside it might look like things come together quickly but actually the process of thinking, talking and engaging with people takes a lot of time.

There was one clear aspect of working for Künstlerhaus Stuttgart and Artspace: they are very efficient. I like to develop the textual elements and the discussion around the exhibition and the contextual framework as much as possible, parallel to the production and the thought process. Sometimes, especially with promotion, [of an exhibition] institutions demand that you as a curator or as an artist develop a press release much earlier than when you know what to show. They want you to close the discussion and give a finished statement.

Here I work with a good team and they understand what time means, especially in New Zealand. In New Zealand, you first look at it and then decide what time it will take, you look at a wall to paint and decide “ah this will take two hours to do” and then it is done. I like this because I think this gave me a lot of time to see how exhibitions were shaped. So instead of saying something which is not in the show or not about the show, instead of representing the discussion, actually we delivered real discussion.

LL: So, with that said, the way I notice we (we being the wider art community) reflect on Artspace is by the various programmes developed by the directors, so you will have ‘Emma’s Artspace’, or ‘Catarina’s Artspace’ [meaning former directors Emma Bugden and Catarina Riva], and now we’ve seen ‘Adnan’s Artspace’. How would you define what you have given us over the last few years? What is your Artspace?

MAY: Difficult question…. We should acknowledge the major architectural changes.

LL: Yes.

MAY: I think in my age; in my position, it would be hard to get the opportunity anywhere else. Mostly you need a long contract…

RdB: Yeap

MAY: …and mostly you need lots of money…

RdB: Yeap

...if you ask me, “do you want to curate another show at Artspace?”, [my answer would be] “not really”, like, I really don’t have anything else to say.

MAY: …and one thing that I can tell you [Adnan turns to Remco] is that when you define the gap, like there’s something to be done, and when you put people in a conversation, things happen.

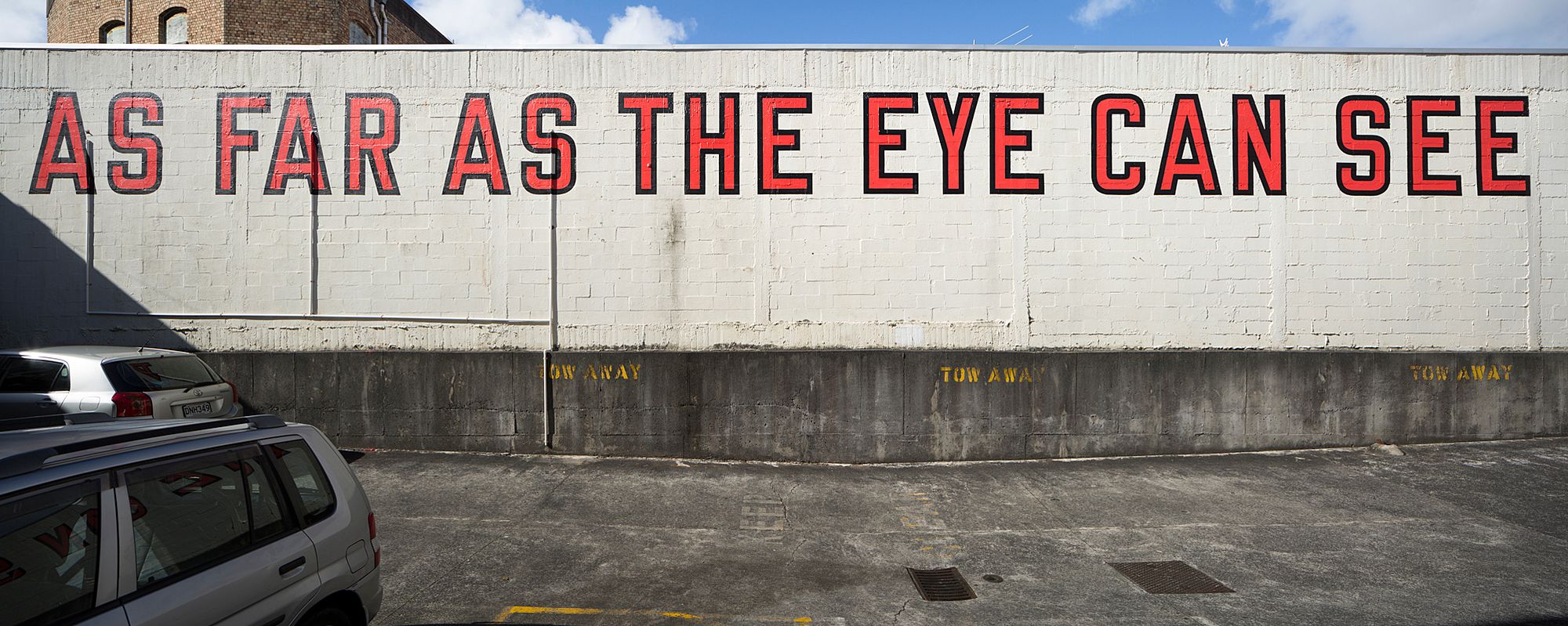

Like when you see the carpark wall and ask “did you ever install an art piece here?” and they say “no, not yet in 13 years of being a tenant in that carpark”, you can start to imagine a Lawrence Weiner piece [in the carpark] and it happens in two weeks. You can work with a tech artist who gives you the same quality that Mariam Goodman demands. So, I think this is something that always seduces me with New Zealand, the simple form of materiality but the precise application of it and its practicality.

So back to the programme, no one remembers an institutional show about queer practices in an historical context [before 2016], so that was something that happened. Actually it’s not a show that I would usually curate, it is not a common show for me. Beachead's Peace of Mind or Too Busy To Think are two typical examples of my curating practice. But many people here would recognise me with The Bill. It was also the first show after the architectural changes, I think it really became an open space. The space feels physically more open, also a lot of people tell me it became a more diverse, pluralistic space. I wasn’t very much interested in how many people come into the space, I was more interested in the differences that reflect on the discussions.

So, architectural change, lots of queer practices being involved and very pluralistic, [a] very open space. I mean I was able to see FAFSWAG’s ball, almost close to the end of my programme and for me that was the most interesting thing, along with No Pride in Prisons, that I have discovered in New Zealand. And it was really good for me to engage them within the process.

After seeing Yuki Kihara, Shannon Te Ao and Sarah Smuts-Kennedy’s shows, if you ask me, “do you want to curate another show at Artspace?”, [my answer would be] “not really”, like, I really don’t have anything else to say. Like if you said ‘what is the gap in the programme?’, I really don’t know, I really have said my statements and that is it.

RdB: But also, Adnan, there are a couple of things which reached the shores of Europe. You talk about the architecture, but one of the things I’ve heard a lot this week, and also when I was in Europe, is that you have done a lot of things outside of the building as well, no? Like the Politics of Sharing which also went to Berlin, and then the other thing which is sort of unusual for me, is the things with the commercial galleries like the Gil Hanly show. Which maybe in part comes from not being able to use this building [for a while, due to asbestos removal], but it is also spatially or architecturally super-interesting to know that you don’t need to use the building, you don’t need to use only the space, you can go outside. There’s not a lot of people who would think that.

MAY: I think, I have to mention that before coming here, at Künstlerhaus Stuttgart and when I was freelancing, I always tried to engage other spaces: these spaces could be public spaces but some of them were dealer galleries. I think that some people might be sceptical of a collaboration with a dealer gallery and a public institution but I can ensure you guys that I wasn’t paid by them.

But also, it’s like how you said we had some offsite projects because of the necessity of asbestos cleaning, which I call a natural disaster. So, it was necessary to go to Lorne Street. We had totally a difference audience profile. But also, with The Bill, which was a collaboration with Starkwhite and Michael Lett, I think I always imagined a queer walk. So, I was not only thinking about within the exhibition space but also about the contextual differences. When you are on K Rd you feel the adult entertainment business. There is a history here, sex workers are always on the other side of that corner. So actually, they give you a lot of inspiration. But also, I am a collaboration monster I have to say, I try to collaborate when I see potentials. I think it is important to engage people. But also from an audience perspective, when there is an opportunity to relocate the resources, that creates a social agenda for the city, when the audience can see part of The Bill exhibition at Starkwhite, in their mind they will remember it was the Pink Pussycat Club, you can’t ignore that history.

So, I think curating means working with inspiration as a practice. And I was lucky to have a conversation with this part of the world, because of things that were not done yet and that excited people and they wanted to take part and actually space and budget were not limitations because people have big hearts and they made it happen.

I think it comes back to the architecture which is so significant: how do you feel welcome in the space?

LL: [Let’s turn to] the FAFSWAG Ball, which has happened at the end of your tenure here. I remember you attended a ball [in South Auckland] almost as soon as you got off the plane, and I think that showed that you were getting out of central Auckland meeting as many people as you could, but also how strong and long you worked on some of those relationships.

RdB: I think it comes back to the architecture which is so significant: how do you feel welcome in the space? And so, they felt welcome in a space which maybe felt unwelcoming before.

MAY: I think they questioned what it meant to take part in an institutional context because they are used to being FAFSWAG on their own. For them to finally be convinced was not only about the resources they were offered but also about the conversations they wanted to have and about safety.

RdB: Yes, and that is so critical. Again. You know maybe you should become an architect, you are so spatial.

MAY: I started a PhD [in architecture] and I never finished!

RdB: But really that is so critical. You know people will think ‘am I welcome there?’, ‘am I safe there?’, and then decide if they are going to come.

...while New Zealand might look smaller on the outside compared to other countries, the cultural climate is so multi-layered and I didn’t know that it was such a complicated culture.

MAY: You need to build relationships with them in order to host them. It is not only producing an event and booking them for an event, it’s not only having them for a night, it’s a thorough long-term engagement.

Thank you for picking up this welcoming hospitality thing: one of the things that will challenge you here that will never challenge you working in Europe is not only the content, but the dramatic change in understanding the context.. [It] brings questions, like “how can you be welcoming to different audiences? How do you engage different communities?” Because while New Zealand might look smaller on the outside compared to other countries, the cultural climate is so multi-layered and I didn’t know that it was such a complicated culture. So yes, it changes your agenda. I would never think about these questions as I am doing now.

I want to ask one question of Remco, is that possible?

LL: Yes, please.

MAY: Because, later we [Remco and I] realised that our relationship is not just a random relationship. I wrote for and produced a monography publication with Ahmet Öğüt celebrating the 10th anniversary of his practice. This comes not only from a long friendship but also an intense exhibition process; he took over the exhibition and studio floors of Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, such a prolific artist. And actually, what we put on the cover of that book was also the work that you produced.

RdB: Yes, that was a project I did with him. I never saw the book until Adnan showed it to me.

MAY: But it’s not only Ahmet. Very early in my practice when I was trying to survive as a freelance curator, I was just trying to apply for these open calls. I got one of them which was with Enough Room For Space and they call it Curator Curator, but also you were a part of it too, no?

RdB: Yes, I also got a slot.

MAY: And now we get to catch up again. So, in our practices there has been a lot of cross over, I didn’t recognise it until Remco showed up at Artspace and then the light bulb [went off]. I think there is a reason, everything has a reason. And I heard that your application was a really good one, and a very detailed one and that you had thought a lot about Artspace. So, I think perhaps it is not a coincidence that we have practices which have come together somewhat dramatically.

RdB: But also, my application was really fun to work on and I made a sort of example programme and so I thought it doesn’t matter if I don’t get it or not. You know you can actually have so much fun making a programme for a year. A part of it will become a reality I hope but that wouldn’t have been possible if I didn’t feel so related to what you were doing [gestures to Adnan] and also for that work to reach me through my computer.

MAY: But sometimes as a curator, that’s enough. You know you go to a park with a piece of paper and pencil, and you can start imagining an exhibition. And you do this because this is a field for thinking. Practicing every day is an interesting way of thinking about curating, I practice every day, I think about exhibition-making every day. You too?

RdB: Yes.

MAY: I think drafting a programme, it’s very beautiful to imagine.

I am really inspired by Adnan’s programme and would like to see it as cues.

LL: So, on that, what can we expect from you Remco?

RdB: I don’t know. I would like to shy a bit away from that. I know there have been lots of directors and you can put a name to that, but I would like to be a bit more modest and move away from the individual curating and authorship thing. I don’t want it to be about a guy that comes in and “oh here is his programme”, although of course it will be a little bit like that, but I really want to think a little bit more long term about it, no? I am really inspired by Adnan’s programme and would like to see it as cues. I should learn from what Adnan is doing and I am really interested in all the people in his programme that I don’t know.

MAY: Can I rephrase the question?

LL: Yeah.

MAY: Because I think it’s interesting to respond to you as a curator. Sometimes, some practitioners with who you collaborate, they come back in certain states that you don’t expect. One of them was Marysia Lewandowska for me. When I arrived here, intuitively I realised I needed to work with Marysia Lewandowska, I needed that public moment. So, how do you expect some key practitioners that you [have] collaborated with earlier (it’s very early to ask I know) might come back? Did you have a moment where you thought one or two people might be interesting for Auckland?

RdB: Yeah I do have a couple of those names, but I am a bit hesitant to name them as I haven’t talked to them. But maybe I should because otherwise it’s floating in nowhere. So, there is one artist Mounira Al Solh who is a Lebanese artist who has an amazing work in Documenta actually, and I was really amazed by it in the Islamic Museum in Athens. And she made this beautiful installation in the space.

She is from the 1980s so the same generation as us but when she grew up in the 80s, Beirut was occupied by the Syrian government. They had check points and tanks which were operated by Syrian soldiers and they were in the city for years right? And now these same soldiers come back with their families, in the millions to the same city they occupied [as refugees] and they are welcomed with open arms. Not like in Europe.

So, she’s been trying to deal with that situation and she has been collecting stories and to work out how that relates to her life and to other historic stories of refugees. It is dealing with very contemporary issues and is a very beautiful, poetic and imaginative work which I am yet to fully understand. But she is someone who I have always had respect for.

AMY: I saw a beautiful work of hers.

I am a guest, I am not here to show my programme, I am here to work with people in order to make sense of the world we live in no? So, I need that safe space.

RdB: I would love to bring an artist like that in because for me if you talk about safe spaces it would be safe to work with her but it would also allow me to start a conversation with people here about how to think. So, for me probably the first slots would be a safe space for me because I don’t feel comfortable yet and I don’t know what people’s concerns are. I want to really be careful about what I do and say. Because I am a guest, I am not here to show my programme, I am here to work with people in order to make sense of the world we live in no? So, I need that safe space.

And there is another artist called Sonia Boyce, that I was thinking of working with as well. And she’s an artist who is very important for the UK scene, and who I really love. This whole Black artistic movement is really only now surfacing which still astonishes me, but I would love to bring her in. I think her work has never been shown here, which is a bit weird as well given that there is still a UK relationship, right?

So, it’s not really showing that I am interested in Syrian or Black art, but rather that bringing these practices in would allow me to start a conversation with everybody and try to find links and learn from how a lot of these Māori and Pacific histories are bigger then we think and how can we connect these with what is happening in the UK. So, these are the kind of starting points I am looking for.

MAY: Thank you for sharing, I know it is sometimes scary to share them before they are cooked.

LL: You worked fairly similarly when you first came [Adnan].

MAY: This is what I am also thinking.

LL: And so, it is interesting to now see your final show is three local artists – Yuki Kihara, Sarah Smuts-Kennedy and Shannon Te Ao – dealing with incredibly local issues and while two of them spent time overseas, they haven’t gone further than the Pacific Ocean, so the patterns there are quite interesting between the two of you.

I have one fairly nosey question, I want to know the advice that you, Adnan, will give to Remco in private, and Remco if you will take any of it on?

MAY: We have a private dinner tonight actually where I wanted to individually have a conversation with Remco and actually it’s not advice, it’s not my position to advise, he is very good curator and comes with a good will but….

LL: Maybe parting words would be a better phrase?

MAY: Yes, totally. As a colleague, I would say try to listen to this context, not only with your ears. Because one of the things I learnt in New Zealand is listening can change your mind, your understanding, your timing etc. but it’s not only listening as we know. I have learned a lot here but not only listening with my ears, I am talking about other forms of listening too...

I wonder what kind of burden that places on you.

LL: I did have one question that I am not too interested in, but I think the community is thinking about it. And that is what it means to have had three consecutive directors not from New Zealand. And maybe that is less of a question for you and maybe more for the board, and us as a community. But I guess I wonder what kind of burden that places on you.

MAY: But maybe we can add one more comment for Remco to understand it, in the way that mostly in Australia and New Zealand curators or directors working in these institutions are from here or Australia, so Artspace can provide this sort of temporary, a little bit precarious position for outsiders who become insiders very quickly. So, I think it is important to host internationals within this map. But I also completely understand the local concerns. Three international curators one after another should of course be questioned, I agree because the position might eventually be for a New Zealander to test the international context.

LL: I think we also ask and question this because when the job comes up we think about which of our colleagues we want there, and this time around there was no one obvious for me. So, it’s not something I bring to the table with an accusatory tone at all, but I guess I just want to give you the chance to respond to this.

RdB: I think it is a great opportunity, for any city, to have other ideas. There is the same discussion in Glasgow.

MAY: Is there?

RdB: Yes, exactly the same, certainly parallel. Sometimes people feel like “why are these international people in here, why do we need these voices from outside?” and that is completely understandable. And then there is also a group who says “hang on, we need these ideas no? We are not international if we don’t invite an international curator over.” There’s also that kind of crew.

MAY: But they don’t hire you just because you are international. They hire you because you are many other things. I understand this question, within the art industry we ask this question all the time, but I think we can ask the same question for other industries and other industries bring international people in and out all the time. Like there is a context in New Zealand of a whole community of ex-pats. They go out to specific bars together and there is an ex-pat culture, so it’s not only us who are questioning this.

...people think we live in a global world but only for a certain group of people is that the case.

RdB: Yes, but it is also a very important question because people think we live in a global world but only for a certain group of people is that the case. For the rest, it can be very difficult if you don’t have the resources or the right passport whatever, so very quickly your mobility goes out. And so, in Europe, like with Brexit, it is going to stop very quickly.

And now art schools are collaborators, they are a part of this horrible process and so they will let you come and study but two days after your study is over and they have sucked your financial value, they will send you home. Five or 10 years ago these art students would go on to set up spaces like RM, which go on to become very important spaces for a city and you contribute, find relationships and be a part of the culture, but that does not happen anymore so it means that these people cannot contribute to Glasgow. So, you get a complete monoculture, the only people who contribute are the ones you allow in that space. I see this in Glasgow, we can’t work anymore with people from Singapore or anyone else outside of Europe. Today it is your passport but tomorrow it will be your gender and the day after it will be your sexuality and the day after it will be something else and more and more we will miss out and this is the threat I see in Europe. And I think New Zealand can learn from Europe about how to deal with mobility and it is so essential, it’s not even about art right? It is how we all function together.

So, when we talk about internationality it’s about mobility and flow of ideas and people and I still think it’s super valuable to be in a space, and to see things and do this interview, and to meet Adnan. I can appreciate his programme but it only starts to make sense when I see him here now, no? What is the threat, we can only learn from each other.

MAY: We are in the age of isolation politics.

RdB: Yes, and that is horrible. Completely horrible.

LL: Well we are three migrants of various stages sitting in an office dedicated to supporting Pacific art and artists, so hopefully this is testament to an openness of difference and mobility.

I wanted to give the last word to you Adnan, and ask if you had any parting words for us in Aotearoa.

MAY: I have a feeling like my relationship with New Zealand and New Zealand artists…

LL: Has just begun

MAY: …has just begun. Yes, actually it is true!