Curator's Tour: Taku Tāmaki at Auckland Museum

More than simply a celebration of Auckland's past and present, Taku Tāmaki is a nod to the future: of this city, and the Museum itself. Simon Gould and Finn McCahon-Jones take us through the exhibition.

The Museum sits on a sloping, grassy plinth in the centre of Auckland's oldest park. It's a familiar sight to anyone who's visited the city. Flanked by smooth stone shoulders, the building stands alone, gazing steadfastly, proudly, into the Waitematā harbour, its northern face gleaming in the afternoon sun. It's a face that inspires reverence. Even the pigeons are quiet.

Round the back's a different story. The other side of the 86-year-old building is less than a decade old, its face temporarily covered in scaffolding. This is where the tour buses stop, where the cafe lives and where Taku Tāmaki: Auckland Stories can be found. Marking the 175th anniversary of the city, the Museum's latest exhibition celebrates Tāmaki Makaurau's past, present and future. It integrates objects with videos with games and a community space. From an immersive recreation of a 1980s dairy to a gleaming Peter Madden island-in-the-sky, it's imaginative and unexpectedly playful - and this is important, too, because not only is the exhibition a celebration of our history, it's a nod to the future of the Museum itself: a first glimpse into how it plans to reinvent its collection over the next twenty years.

We toured the exhibition with Taku Tāmaki curator Finn McCahon-Jones and exhibition developer Simon Gould.

Simon Gould

Welcome to Taku Tāmaki: Auckland Stories.

It's a show about Auckland.

Finn McCahon-Jones

And not just the last 175 years, either. We've gone back —

Simon

— whether it's been called Auckland or otherwise. It's a celebration, basically. Before we even got to decide on the components of the show — where the objects would be and blah blah blah — there was so much attention to this, so many different voices that needed to be heard, and wanted to be heard, and even the notion of doing one exhibition about something as big as Auckland is ridiculous.

Finn

I was born in Auckland, I grew up in Auckland, I love Auckland. And initially I thought: Great, this is going to be so much fun! And then everybody starts giving you a story. At the beginning there was just a folder with 500 bits and pieces.

Simon

So where do you even vaguely begin, while still necessarily having to make sure that as many different people, different culture groups, different collections within the museum are represented across time?

Finn

And that was one of our objectives. This was a celebration of our collection, so we were trying to get as many different objects from all the different collection areas to show visitors that we actually have a really broad and deep collection, so we ended up having to make a grid, plotting things and going: okay, this is old, this is new, this is natural history, this is human history, this is Māori, this is Pacific, this is Chinese - and looking at that and figuring out what we didn't have.

Simon

There's a really interesting divide between what we hope you experience as a visitor — which we hope is quite a fluid experience, re-enacting the real experience of when you come to a city — you meander around, you wander, you bring your own knowledge and experience to whichever point you're standing in, and you try to make meaning of that. So we hope that's the experience you have as a visitor, but behind that, as Finn said, is actually this really quite rigorous process to make sure we've captured all that we wanted to and needed to capture.

Finn

We didn't want people to feel like there was a prescriptive way of going around the exhibition. We wanted it to be free to be eye candy, letting you wander. The main components of the exhibition are places, objects and people. The objects, which we call constellations, are clustered around themes, so here [points to clusters of objects around the room] we've got sugar, rock, waste, wind, voice —

Simon

They're all words you don't need to have specialist knowledge to come to. It's traditional that a museum will present you with themes and topics that often have quite grand ideas behind them. You lose people along the way. So we didn't want to do that. We wanted to make it as accessible as possible. So they're all words — if I say any of these words to you — anyone will have an idea. It'll be a different idea, but together they're things that are around us, that make up the lived experience of Auckland. They're not unique to Auckland, but they are definite connections.

Finn

There's that essay by Foucault on heterotopias, which is about how different layers exist in the same place and how people use and see space. For me it was that same thing with these words. They allowed us to have these multiple perspectives on this singular topic, and it allowed us to get away from notions of time because Māori and Pacific cultures especially have very different concepts of time compared to Pakeha conceptions of time, so we were able to use anything from any time and put them all next to each other because they're all still relevant and they all still exist side by side.

Simon

We called them constellations. They're not actually called that in the public domain. That was our working metaphor because it's this idea that when you look up at the stars at nighttime, and draw a line between the four dots that we see up there — those dots, some of them may not exist anymore. They're certainly in vastly different places in space and time, but we see them together. And when you stand in the middle of a city and look at a piece of architecture that was built 100 years ago, the stone was taken from somewhere else in the world but there's a person next to you who was born and raised here, and there's a thing in your hand that's made from plastic from the sea, from oil — you know, everything's coming from all over. So that's what we tried to do, and the words helped us access those. And hopefully they're quite fun as well.

Finn

This is by local Auckland potter Peter Lange — it's an outline of Rangitoto as it sits in the Waitematā made out of bricks, talking about our local ceramic history, but we're also using it to talk about a natural history idea of why Waitematā harbour is so still and beautiful. I always think of 'Waite-matā' - water of the obsidian, so you have that beautiful picture, and all people living in Auckland know that summer day where it's like the water's been scalloped, or carved. Every single point glistens. And it's because of Rangitoto, plugged in the front, that we've got this beautiful, still harbour. If it wasn't for Rangitoto, we'd all be surfing.

Simon

So matching that story, which is a natural history story, or a geology story, with a contemporary artwork is something we wanted to do. We aren't here to explain objects. We're here to ask as many questions as we're answering, so hopefully you enjoy the story, you enjoy the object, but you also feel inspired to think about the city in a new way. You'll find that every single object's story talks about a particular point in Auckland. It locates it. So the next time you're looking at Rangitoto you might think about this.

We aren't here to explain objects. We're here to ask as many questions as we're answering, so hopefully you enjoy the story, you enjoy the object, but you also feel inspired to think about the city in a new way.

Finn

I like these insects above [Rangitoto]. It prompts you to go around to the next one.

This story is about wind too, of course, and all of these locusts, blue moons and monarch butterflies are not native to Aotearoa. They've come across on the wind. And there's this lovely — I think it was our entomologist talking about this — but there are accounts of people in the middle of the ocean suddenly getting surrounded by a swarm of butterflies as they make their way across the ocean.

Simon

Yachties just swarmed.

Finn

And then they keep on going. And so things like the monarch butterfly arrived and established in New Zealand, even to the point where there's a Māori name for them. However, blue moons — they make it here, but they usually die on arrival because of the climate. It's too cold. And then other things are getting blown over.

Spiders do a thing called ballooning where they let out a trail of silk until the silk is long enough to catch in the wind, and they go shooting up into the atmosphere. They fly along until they come along to land. So up in the atmosphere, at this moment, there are a lot of insects travelling around, so for people who hate spiders this is a really freaky notion. But then thinking about how we're ultimately connected: yes, we're a small island at the bottom of the Pacific but we've all made a journey to get here.

Finn

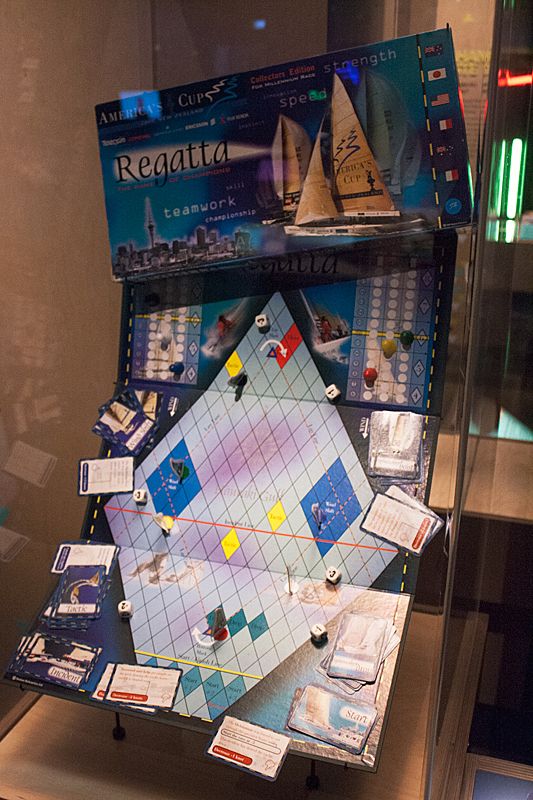

This one's kinda funny because when the show first opened, the America's Cup wasn't going to get funded again and there was all this uproar. This is a game that was made in 1995 for the America's Cup. It's a sailing game — you get these tactic cards, these wind cards. We played it to see what the board would look like. I actually really enjoyed it.

Simon

It was much less boring than I thought it would be.

Finn

So talking about these elements — yes, it's a board game, but it's also talking about the broader industry and our obsession with the water.

Simon

It suggests the history as well, of first arrivals and how Māori have not just paddled but sailed for hundreds of years.

Finn

That's another thing, talking about Te Reo Māori — all around the exhibition we've got bilingual text, so all the constellations have [gestures to the wall] Te Hau, and then Wind, so the Māori first and the English second, and all the way through we've put Māori words into the text with the conscious decision not to have a unique Māori text because people who can't read Te Reo Māori will often dismiss it and not read it at all. We want people to encounter Te Reo and to read it.

Simon

We do want to make our visitors work a bit as well. Which comes back to one of the fundamental points of this show — which is also one of the only ways you can deal with a subject as big as Auckland —which is: this is not an encyclopaedia. It is not the museum's role anymore to broadcast expert knowledge at our audience, expecting them to sit at our feet and listen. It's a conversation, so in that sense we formulated the show — the metaphor we used for that was 'as a fieldguide'. So what do you do with a fieldguide? You take it with you when you're going on an exploration and it aids and assists you in identifying things around you. It's an aid to interpretation, but an aid rather than a textbook.

It is not the museum's role anymore to broadcast expert knowledge at our audience, expecting them to sit at our feet and listen. It's a conversation

Finn

It was also about thinking about people who are Aucklanders. We were making it for them, so we wanted to give them stories which were a twist on something they already knew, or a slightly new version, something interesting.

One of my — can we go down here — one of the things was that I really wanted to put a bag of chips into the exhibition, for the reason that it's such a pedestrian object. It's so everyday and putting it in the context of a museum, this rarefied space — for a lot of people it's been interesting watching them, because firstly they laugh, but then they kinda engage with it and think about it not as a bag of chips but as an object that has been made and belongs to the city, and has this other identity around it.

So we've got this video of the chips being made. It started off in the '50s, being made for people at the speedway, for snacks, and it got bigger and bigger and turned into this thing here. For me, one of the messages — all this exhibition is — is that everything has a history, and you can make a choice to see those histories. With a product, you can do your homework, you can support local industry — we should be thinking of those things. It's an act of mindfulness.

Simon

Of all the different places you choose to visit or go to, the Museum is the one place you can go where these collections are held, so it's the enduring responsibiility of the museum to make objects accessible, interesting, as well as looking after them. But to make an exhibition you also need other types of experience, and when you're looking at a city, we found it useful to think of the city as being made of people, places and things. So if these are the things, well, you can't separate the people from interpreting them, but another place is the studio which is one of the most interesting areas of developing an exhibition.

We're very used to museum exhibitions being static experiences, and in more recent years we're also used to having public programmes surrounding exhibitions, usually outside or nearby, and maybe people come for a talk and then they go for a little tour of the show, but to me they need to collide and intertwine with each other, so this space is about seeing the people of Auckland. On a daily and weekly basis, this space is populated by different community groups. Hobby groups, showing off what they do. We've got the deaf community coming to do sign language workshops, we've got Māori and Pacific language week. And you just drop in, take part, learn some new skills, have a conversation with a real person, and then to my mind, it can only benefit how you then go to see the objects. It further enriches them.

Finn

The idea is that this is like a community hall within the exhibition.

Simon

It's a bit of walking the walk as well as talking the talk. Because we talk about being in conversation with our audiences, and not putting the museum on a pedastal, but hopefully a way of actually getting that a bit further.

Finn

We've had, on average, about 1,500 people through the door per day, so it's been great.

Simon

We also upped the levels of participation and contribution around the show, so there are places you can write down your thoughts. We try and find ways to make it less static, and some people learn better that way as well. Some people want to press buttons, some want to talk, and some just want to read and learn —

Finn

We were really conscious of making an exhibition for all those types —

Simon

And making it fun. I don't think anyone ever has a good time anywhere unless you're happy to be in it.

The Pantograph Punch

How long were you developing the exhibition for?

Simon

I came on in August last year, so 9 or 10 months.

Finn

I was on it since March.

Simon

So basically about a year. Which is a really, really short time to develop a show from scratch.

Finn

We had a lot of people bringing their expertise — we had an exhibition developer, a curator, a 3D designer, a graphic designer and a production manager.

Simon

There's a lot of things we tried and tested with this exhibition, and it's good — we've been given a lot of freedom. Putting something - to be frank - as expensive [as the Collect and Connect game] in the show and not be told it has to be perfect on day one is a big deal for a museum, so we developed that knowing we'd have an iterative process, that we'd see how it behaved and make changes as we go along, and make it better. And it should be like that, but it normally isn't.

Finn

It's the same with this whole exhibition. We were told to go and just have fun and make a show, and yes, we had a whole lot of constraints but we were given real creative freedom and to do a show that the Museum — the Museum has not done a show like this before, based around concept and theme rather than subject matter, and internally it's been a real success which makes life a bit easier. But hopefully we've made a bit of a headway in thinking about how the collection can be used in different ways in the future.

The Museum has not done a show like this before

Simon

And that was a big part of it — over the next 10 or 15 years, 20 years, the Museum are redoing all their permanent galleries. There's a document — kind of a philosophy almost — which is called Future Museum. And this was really the first chance we've had to play with some of the ideas in that and show people how it could work.

Finn

So there is a desire and a hunger to do things. And all the curators and everybody wants to start playing with ideas. We're a bit more established with how we think about things now, plus there's all that idea of how we consume information. We want different things, as visitors. And yes, we're probably a bit behind as a Museum, but the gears are big in this place. We're getting ready to think about the collection in more dynamic ways.

Taku Tāmaki - Auckland Stories

is on until Sun 18 October

Finn McCahon-Jones (curator)

Alongside being a curator at Auckland Museum, Finn is the host and producer of the Kid's Show on BFM and has a long involvement with not-for-profit art spaces in Auckland. His publications include an essay in ‘Bespoke: The Pervasiveness of the Handmade’ (Objectspace, 2006) and co-writing, ‘Fingers: Jewellery for Aotearoa New Zealand’ (Bateman Publishing, 2014).

Simon Gould (exhibition developer)

Simon was the exhibition developer on Taku Tāmaki – Auckland Stories. He has previously won awards for his work at University College London, where he was Contemporary Projects Curator. A natural fan of all things interdisciplinary, Simon helped to pioneer exciting new ways for the museums to reinterpret their collections, engage different audiences and generally to work in new and genuinely innovative ways