Distant Stills in Our Lives

It's a condition of doubt. Of obsession and anxiety; all-consuming and devastatingly debilitating. Stuart Wall looks back on a hypochondriac self that's no longer his.

I’ve been trying to remember a singularly painful and disastrous period of my life, an experience that coloured every aspect of my world and rendered my senses, belief in myself as a rational person and time itself untrustworthy: a time when I was a consummate hypochondriac. I recall my actions and their contexts; I recall with whatever degree of accuracy is granted us in recollection the gist of my thoughts and perceptions; at times I can access the emotion. But I can’t remember the feelingof my body, the contours of a mind in such an extraordinary mode. This led me to think of my former self as another person, which recalled to me a Jorge Luis Borges essay I once read called ‘A New Refutation of Time’ in which he makes the stunning proposition that there is no such thing as ‘the life of a man,’ nor even one night in his life. ‘Each moment we live exists, but not their imaginary combination’.[1]

*

Tell me where dwell the thoughts forgotten till thou call them forth – Blake

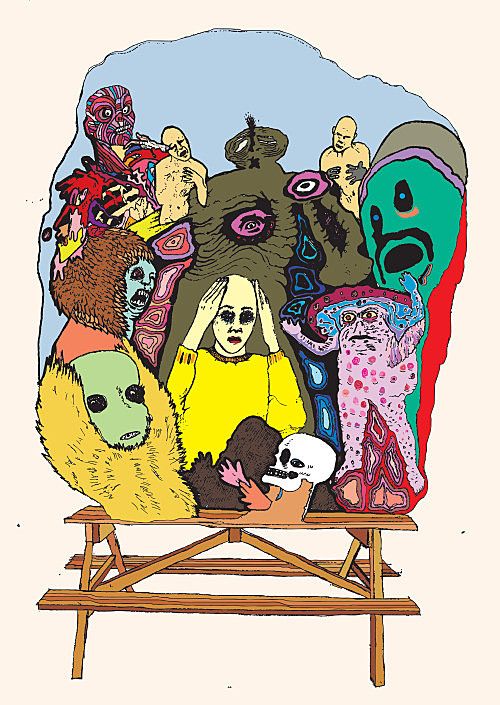

Among the fat black ants that infested our Staten Island duplex unit, one image nested deep in my psyche: a talk show audience watching a satellite projection of a young man in a hospital bed, disfigured, full of tubes, vague, moribund. Born in 1982 I had seen as a small TV-circumscribed child the horrors of AIDS in America.

Scientific knowledge carries on expanding though we stop paying attention; after high school no one has a formal obligation to keep us abreast of important, relevant (to us) developments. How easy it is to miss the demotion of Pluto from planethood or the construction of the Hadron Collider let alone substantial advances in medicine. In 1994, for instance, David Ho pioneered anti-retroviral therapy, the first major breakthrough in HIV/AIDS research in a decade. It occurs to me now that I was twelve when this happened, but sex ed. did not, to my recollection, teach us about it. A friend shares the same experience – ‘Until you told me otherwise I thought an HIV diagnosis was still categorically a death sentence’. Frozen in my relation to scientific conditions of the 90s the picture of that dying boy, hushed in its neural album, was not to lay hidden forever. This is not to say that my awareness of anti-retroviral therapy could have done much to mitigate the picture formed in my childhood. The descent into hypochondria is anything but rational.

What might have done the most to suppress this picture (and others that comprised a healthy fear of unprotected sex) was the greater fear of pregnancy. Wait, you’re thinking, don’t both considerations lead to the same precautions? Not always. My sister got pregnant at sixteen. The father left town. The ramifications of the pregnancy went beyond anything I could imagine. One of them was an extreme, obsessive fear of unintended pregnancy. A Hamlet-esque brooding obsessiveness had always been a core part of my personality. Add to this the active agent of irrationality and you’ve got prime conditions for hypochondria.

The extraordinarily unlikely is credited and embraced by the hypochondriac. So one asks, when he’s twenty and his girlfriend’s period is a few days late—though he’s yet a virgin—a question like ‘Can sperm travel through clothing or material?’ The answer: ‘If the clothing was completely saturated with semen and was in direct contact with a woman’s vagina, there is a very slight chance the sperm could enter the vagina, but this is highly unlikely. No conclusive studies have been found to give a definite answer on this possibility’. The operative words: ‘no conclusive’, which translates to a hypochondriac as, ‘you bet your life it’s possible’. This of course leads on, through a magic tunnel in the brain, to ‘it’ll be a miracle if she’s not pregnant’. The following six days until her late period arrives are one protracted nightmare of projections, false resignations and fraught secular prayers.

*

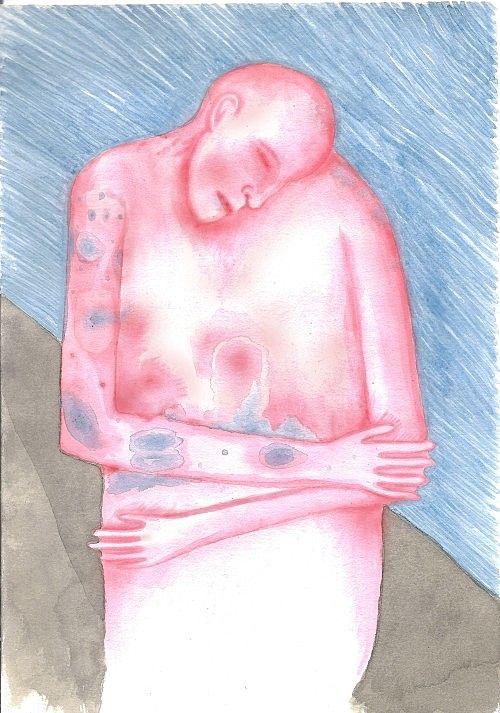

24, glassed in a jagged world of deep illness – at its worst held me top of the stairs – through the slow hours before dawn, clenched – foetal with a strident sensation like some dark inoculation inching through my arms – beating dead hours before someone drives me to the A&E – helpless – lost to the peopled world. A different person.

In 2005, after crawling across the finish line of my undergrad degree in New Jersey, I moved to Portland, Oregon: mecca of progressivism, unemployment, and cheap drugs. Manifest destiny. I flatted with six twenty-somethings in a smallish house overgrown with shrubs and roses (‘City of Roses’) strewn through the garden pergola leading to the front door. A small porch with hanging plants. A few shitty bicycles rusting against the curvy wire fence alongside the house. Inside, dark brown lounge carpet, motley blankets shrouding holey couches, a large kitchen with an orange peninsula and wooden cabinets, fluorescent ceiling lights, retro faerie lights. An old turbine roof vent measured the percolation of stoner time on the asphalt roof shingles, good for sneaker traction and reclining into the sunset. Perfect summers, rain nine months of the year.

I got a job cleaning at a fancy cookery shop in the ‘Pearl District’ three mornings a week and waited tables part-time at a chain restaurant in a miserable peripheral suburb mall. Took two buses to get there. Two back. With no friends apart from my flatmates; with my guitar and guitar-generated confusion; with my constitutional sense that ‘life is elsewhere’, I floated through concerts, cafes, over footpaths, bike paths in a wide gyre toward the centre of the action. I would never get anywhere near the ‘centre’—the gyre only widened. A tense atmosphere soon replaced the honeymoon of the first months of new flatmates; daily cohabitation sharpened our faults and incongruities. Dirty dishes. Privatisation. Schism. In mildewed basement red-lit pot ether: Adam and the members of unstable alliances playing a combat video game continually as if to exhaust the technically finite permutations of fights, bringing about the eternal recurrence of that grim universe. Borne along this night river I didn’t see the rock just under the surface ahead: the action.

In February 2006 I had unprotected sex with a girl I barely knew who had taken a seemingly airtight contraceptive precaution: and intrauterine device (IUD). Eight yearssince my sister got knocked up, eight years of obsession on this one thing to avoid at all costs, this thing that had caused such destruction and sickness at home—was it this that blinded me to that other danger, that picture gathering dust in the back of my mind? For a week or two it didn’t register. Then, like a tap on the glass that disturbs and confuses fish, the realisation, from outside, knocked. And knocked. And signalled in its obscure semaphore. Another week of growing disquiet. Then, as though suddenly discerning in that strange, incomprehensible motion the awful frenzy of a thousand ants, it fully came to me. At the bar with friends. Playing Trivial Pursuit in mounting agitation, with a violently shaking hand I awkwardly chucked the die, which careened right off the table. I apologised and bolted.

Thinking back to the me of this story as I remember it—quixotic, socially colour-blind, slack, bad with money—I wonder, who is this? He bears little resemblance to the (relatively) learned, disciplined, chilled-out, thoughtfully idealistic, job-maintaining Kapiti Coaster writing these words. It was not at all inevitable that the one should become the other. The former is like some tragic second cousin, the kind of person of whom you might say with a knowing sigh at human frailty, ‘Some people’s lives you can see all stretched out before them like trees. Who couldn’t see what would happen to him?’ It’s only natural to think of a continuous self at various stages of development, but to what extent are we really the same person we once were?

In a counterintuitive theory offered by Borges in ‘A New Refutation of Time’, he discusses Idealism, defined by the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy as ‘the theoretical position that phenomena and events exist only in so far as they are perceived as ideas’[2], and extends its position to include time. He can find no compelling reason, after empiricists David Hume and George Berkeley have denied the existence or knowability of a human self or soul [3] and the existence of matter [4], that time should be left intact. He arrives at the conception that ‘each moment we live exists, but not their imaginary combination’. This is a rejection of the continuity and integrity of the self. If moments in our lives are non-sequential, then imagining one’s ‘former’ self is based on an illusion, the illusion of a continuous self, photographable at any given point on the line along which it proceeds. There is a strange disjunction between the various selves of distant stills in our lives.

After the Trivial Pursuit scene at the bar I had my first panic attack, which lasted four or five hours. That night I would take the first of many fruitless trips to the A&E, heart pounding, face red with dried tears, body answering extreme anxiety with corresponding physical sensations. This new compulsion put me in a tough spot. Without health insurance, I couldn’t afford the exorbitant bills that came with a visit to the A&E, the doctor, or the therapist. The light at the end of the four months was grad school: students get health insurance. But that was a long time to get through. Time as an obstacle. Time as the enemy. Life itself as the enemy—for what is life made of? Time not simply to be wasted but to be beaten to a bloody pulp. Time I would sooner have been unconscious. Experience, whatever we may believe intellectually, tells us time is real.

I decided that very night to fly home to New Jersey in three days’ time. I couldn’t make it on my own three thousand miles away—I needed an adult, a maternal figure. So I spent the summer with an ex-girlfriend’s family, in hiding. I couldn’t let my mother know I was around; she was incapable of helping me and I was concerned at this stage only with self-preservation. They were wonderful. The mother, a nurse, demonstrated in her actions and words all the angelic virtues her profession is known by. The others aligned themselves with her example. My ex gave me her full support, with strength and compassionate subsuming the complexities of our relationship.

Only once did I touch a boundary and was made aware of my transgression in no uncertain terms. One night I went upstairs, too afraid to be alone. I asked the teenage sister (my ex was away) if I could sleep on her floor. Then, at five or six am, one of those hyper-memorable moments bathed in the combustible light of liminal awareness: her mother woke me up: ‘You’d better go downstairs. Frank would be very angry if he knew you were up here. She’s just a kid. She shouldn’t be involved’. Rightly or wrongly I felt crushed. It was only sleeping on the floor. I just needed human proximity. I didn’t involve her. Hypochondria alienates. I never felt lower than this.

I had been, up until this point, too afraid to get tested for HIV. Even this dismal, ultra-lived existence where I obsessively pulled up my sleeves to check for skin aberrations, felt my glands for swelling, suffused the guest room with nightmares so that it knelled in its tidy whiteness the leaden chime of my doom when the others went to bed and I was left alone; this purgatorial uncertainty was better than a positive test result. But as the summer wore on this became untrue. It was not a life worth living. I had to get the test. There was no other way out. I couldn’t be someone else’s child indefinitely, couldn’t be a child at all for much longer.

The five necessary conditions for contemporary hypochondria as advanced by Catherine Belling in her important study A Condition of Doubt:

- the body’s opacity and mortality

- the patient’s fear that disease is present in that body

- the physician’s inability to find supporting objective evidence for the patient’s subjective experience

- the patient’s access to information about disease and medicine that leads to unrealistic expectations of medicine and distrust of the individual physician’s reassurance [to which I would add the opposite case, that hypochondriacs can create unrealistic expectations just as well with a lack of information as they can with a surplus. I’m thinking of my own experience]

- the matrix of cultural narratives about medicine, disease, and the body that exacerbate the tension between patient’s doubt and doctor’s reassurance [5]

The first condition is easy to read right over; it sounds simple and obvious enough. Of course the body is mortal, of course it’s opaque. But this opacity is the crux of the condition. It’s hard to overestimate the complexity of the human body; it’s been said the brain is the most complex matter in the known universe. This complexity means we can’t know everything that’s going on in our bodies and therefore can’t always catch diseases and conditions in their early stages. This state of affairs is unacceptable to the hypochondriac, but it couldn’t always have been so. The third condition, that we live in an age of democratized access to information about disease and this leads to unrealistic expectations of doctors, renders the field of medicine’s limitations intolerable. I remember once expressing this very feeling in desperate outrage to a friend at grad school. We were at his cosy, Midwestern college town apartment playing music and, as all too often happened in those days, a crescendo of anxiety and fear found its way out through my eyes. Hunched over, crying and crying I said something like, ‘All I want is to know that I’m okay. Isn’t this the 21st century? How, how is it possible that they can’t just test for everything, see everything?’ And on and on. Because of my distorted sense of medicine’s epistemological state of affairs—I can offer no better analysis—I had by this time developed a general fear of terminal disease, cancer above all. My hypochondria had generalised from the fear of HIV to a fear of all catastrophic disease and a suspicion that such a disease could be developing in its early stages.

The unexpected and crucial condition in Belling’s list, at least for me, is the last one, ‘the matrix of cultural narratives about medicine, disease, and the body that exacerbate the tension between patient’s doubt and doctor’s reassurance’. Films, public health ads, talk shows—like the one I saw as a kid—magazine articles, ‘a friend of a friend’ stories, office talk, and wider cultural narratives ‘regarding health, responsibility, bad habits, self-control, and the danger of complacency, and, of course, death’ are all elements that form an environment in relation to which the hypochondriac experiences his/her afflictions.[6] The early history of AIDS in America and its corresponding cultural narratives coincided with my formative years. These were central to the genesis and course of my condition.

The result of the test? Negative. Waiting outside the clinic for my ride in the wan sun, watching strangely benign traffic, I tried to suck the marrow out of my relief. A new life. Life drained of the yellow chemical wash that turned every lounge into a waiting room, every late night diner into a ferry and every friend into its Charon, keeping me afloat and half-distracted on the way to the great agony. Trees were trees; birds, birds.

How long was this bliss to last? Less than a week. I went home. Gave myself up to the gravity of my dysfunctional home and paid the price. I confided in my elder sister what I’d been through and she reciprocated. She too had once needed the same test, but years ago, when the procedurewas different. How long had it been between my indiscretion and the test? Five months. ‘Oh that should do it. It takes six months to be sure; there’s probably a 99.9% chance you’re fine.’ And with that remark, ‘the kingdoms of his life all shifted down a few notches’.[7] I was plunged right back in. 0.01% was the same as 50% to me.

After those torturous months I had finally calibrated my sense of the passage of time with the soporific drooping clocks of Dali, and with a few thoughtless words it was violently jarred back, condemned to the unnatural present by uncertainty—opacity—and an unfaceable future. That is to say, we tend not to live in the present, which some people say doesn’t exist, and others call eternity, except when compelled to by our bodies or wills. During my stay with my ex’s family I had planned a cyclingtour to keep myself focused and looking toward the future. In late June, against my better judgment, I chose to follow through and lift myself out of this state. Looking back it could be seen as an attempt to overlap one kind of present tense with another, better kind.

The plan was to fly into Wichita, Kansas, ride thirty miles north to the TransAmerica bike trail and head east toward Virginia and then home. Impetuously I turned west, the Rockies arranging my longings like so many iron filings. So far, so good. Feeling free and wonderfully distracted in that oceanic yellow prairie. But it wasn’t long before my anxiety started gaining ground on me. A few days later I found myself alone on a picnic bench in the middle of nowhere, thirty miles outside of some hole called Sugar City, Colorado. The winds raged against me on an angle; I could barely stay on the road. I started feeling those dark sensations in my arms and pelvis and I stripped naked to check myself for signs. A new infinitesimal mole was the harbinger of cancer. It found me, even out here among the distant ghost towns and apocalyptic winds. Next thing I’m on a Greyhound bus. A dark vista opening.

Help came at last at the end of August. A psychiatrist at school—health insurance at last—helped me first to say the letters whose invocation terrified me as if I were calling down the unfavourable influence of a planet—HIV. I got tested again: negative. This helped. I drew nearer to believing the diagnosis, however marginally; the requirement of my sister’s outmoded rubric was fulfilled: it had been seven months. But this assurance by definition could not be the end of my hypochondria, and it wasn’t. I was only halfway through the battle and still had many cries to cry at inopportune times, rendering myself un-dateable; had cots and floors of various acquaintances—my ‘enablers’ as some might have it—to sleep on, avoiding the loneliness of my shabby boarding house and its tenants at the edge of town. Somehow it came to an end.

This by way of—who else?—Father Time. As an agent of convalescence he serves us better in certain circumstances. An exceptional psychiatrist; health insurance; a few unconditional friends; temporary freedom—via student loans—from stressful financial concerns and the need to work; an institution and its community’s support of my ego; fulfilling creative work to engage my mind and condense my experience of time: these were all important factors in my progress. I was incredibly lucky. By the summer of 2007 I was stable enough to attempt and complete a cycle tour. In September I fell in love.

The psychiatrist enabled me to see and, for the first time, attend to the underlying problem. Hypochondriawas the most recent, indeed the climactic manifestation of a lifetime of what’s known as Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): an anxiety disorder ‘characterized by (1) recurrent and persistent thoughts, images, ideas, or impulses that cause the person distress…and are beyond one’s will to stop [and] (2) repetitive behaviours….the person feels compelled to perform in response to an obsession and often with rigid rules intended to ward off distress or the occurrence of some dreaded event’.[8] and so on. It is a condition pop psychology has watered down in the late 20th century—‘I’m so OCD about x’. Essentially it’s become synonymous with fastidiousness. Is it better to have a condition diluted or stigmatized out of credibility?

A brief note about how this stuff works. ‘Neurons that fire together wire together’. This formula attempts to explain ‘associative learning’, in which simultaneous activation of cells leads to ‘pronounced increases in synaptic strength between those cells.’[9] In terms of OCD, obsessions are reinforced by acting on the associated compulsions, strengthening the relationship between them, increasing the synaptic strength between these cells. You think about AIDS, you check your arms for skin aberrations. This action reinforces the obsession. The compulsion part of the equation need not even be necessary to strengthen the connection. Simple proximity can do the same work. So you think about AIDS as you pass through the doorway. Later that day you do it again. Now the action of passing through the doorway and the thought of AIDS are connected. Do it again—the connection is bolstered. Now you can’t perform this action without the corresponding thought. And then the anticipation of the action makes another connection. As you do the dishes the thought of having your teeth knocked out comes to mind. Soon hot water and dishes unfailingly produce the unpleasant image. Every time you even approach the sink with a dish it pops into your head. Left unchecked the neural forest with its rank undergrowth grows so thick it blocks out all sunshine. After a few weeks every movement of your knees and elbows is knocking out someone’s teeth. All space becomes a sort of cluttered obstacle course.

My psychiatrist provided me with the cognitive tools, the neural machetes, to cut through these connections. Geoffrey Schwartz’s Brain Lock was invaluable. Soon I had a belt of custom-made tools all my own, e.g., thinking of a butterfly when passing through the doorway; forcing the butterfly to interpose itself between the bad thought and myself, over time replacing weeds with flowers and ultimately with sweet nothing. I got things under control with hard work, diligence and time. But ‘the force that through the green fuse drives the flower’, the Schopenhauerian will or whatever you like keeps coming. One has to be a vigilant gardener. One mustn’t leave one’s tools out in the rain for Father Time, healer of wounds, drier of dishes, conqueror of mountains, his cells, perhaps, scattered across the universe, to ruin.

‘Isaiah and God saw things differently, I can only tell you their actions.’[10] This line, from Anne Carson’s poem ‘The Book of Isaiah’, rejects omniscience in favour of objectivity. The line comes back to me as I wonder about that former self. Odd to reject omniscience, though one’s narrative be in the first-person.

How does one remember experiences but not the feeling of them? Is it even possible in a memory to isolate our feelings as such? Can one be a detached, not to say perspicacious, observer of one’s former self? I don’t know. But obviously we can never re-experience the memory in its original context, cannot recreate with uniform precision its elements in a thought experiment, and this means the experience is consigned ultimately to its unique complex in the past. It’s not dead as such. It’s like a big fish pulling on your line: your sense of it is restricted. This brings to mind Heraclitus’ famous fragment, ‘You cannot step twice into the same river’. Borges admires its ‘dialectical dexterity, because the ease with which we accept the first meaning (“The river is different”) clandestinely imposes upon us the second (“I am different”)’.[11]

Notes[1] Jorge Luis Borges, Ed. Donald A. Yates, James E. Irby, Labyrinths (USA: New Directions, 1964), 223. [2] ‘Idealism.’ The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (2 rev). Oxford University Press, 2012. Victoria University of Wellington Electronic Resources. 15 July 2013. [3] from Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature: ‘[Selves are] nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions which succeed each other with an incomparable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and motion’. [4] from Berkeley’s A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge: ‘All the choir of heaven and furniture of the earth, in a word all those bodies which compose the mighty frame of the world, have not any subsistence without a mind’. [5] Catherine Belling, A Condition of Doubt: The Meanings of Hypochondria (USA: Oxford University Press, 2012), 17. [6] Catherine Belling, A Condition of Doubt: The Meanings of Hypochondria (USA: Oxford University Press, 2012), 11-12. [7] Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red (New York: Knopf, 1998), 39. [8] ‘Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.’ A Dictionary of Psychology (3 ed.). Oxford University Press, 2012. Victoria University of Wellington Electronic Resources. 17 July, 2013. [9] Carla Shatz, ‘The developing brain’. Scientific American 267 (1992): 60–67. [10] Anne Carson, Glass, Irony and God (USA: New Directions, 1995), 107. [11] Jorge Luis Borges, Ed. Donald A. Yates, James E. Irby, Labyrinths (USA: New Directions, 1964), 223.