Don't Make Fun of Me, But -

On Declan Greene's Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography and the death of the online confessional

On Declan Greene's Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography and the death of the online confessional

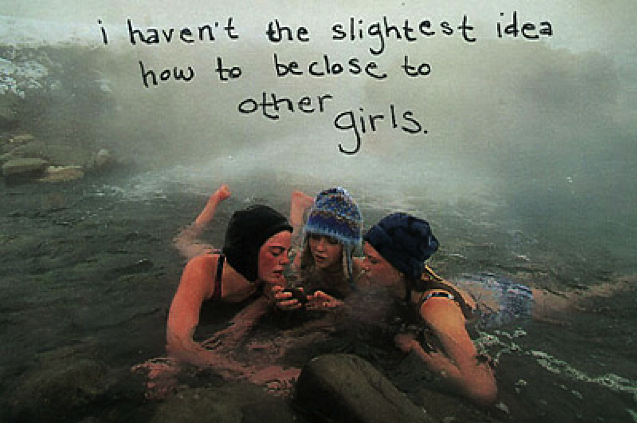

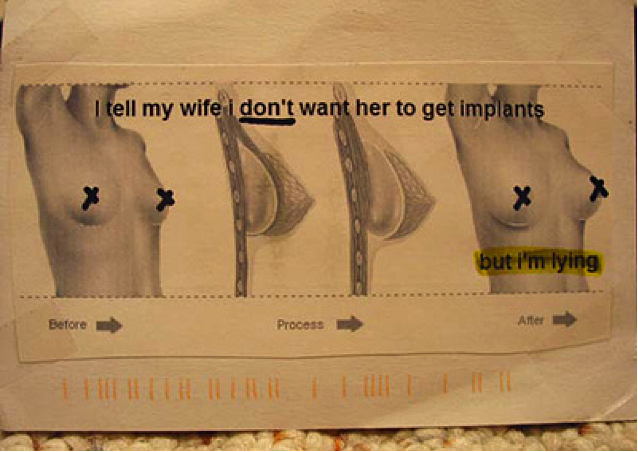

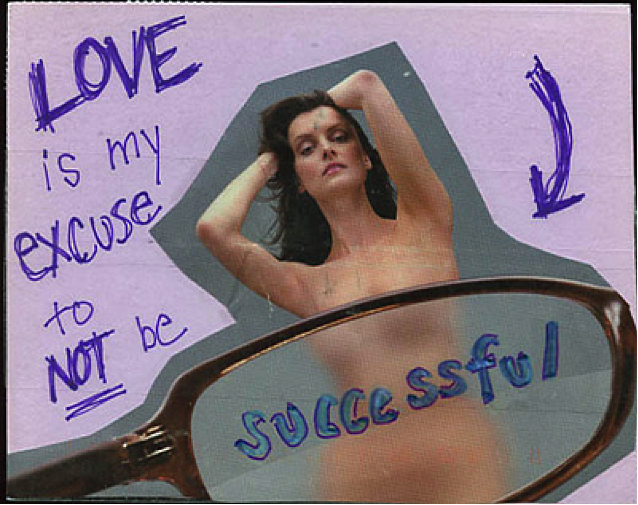

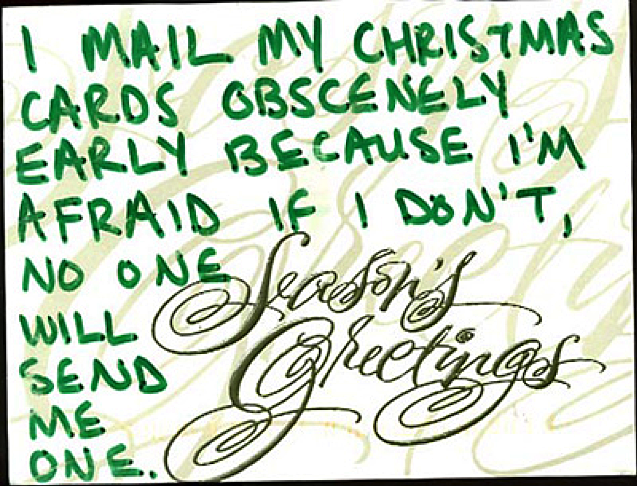

2005 was a momentous year for the internet. YouTube launched, Google rolled out their mapping services and Facebook dropped the ‘the’ from their name and went international. It was also the year Frank Warren embarked on PostSecret. Envisioned as a public, modern-day confessional, it invited people to anonymously mail in the things they wish they could say, but for whatever reason couldn’t, on handmade postcards. A curated selection was then posted on the site every Sunday night, much to the delight and voracious hunger of its largely teenage-girl audience.

While occasionally veering into the branch of serious issues that warranted further attention, they were mostly the types of twisting anxieties and regrets that people had deemed inappropriate for their IRL conversations. Unsurprisingly, readers recognised themselves in many of these, and the project became an instant hit. It was a kind of group therapy, a reminder that people weren’t alone in their shame, and its anonymity meant that people sharing their secrets were simultaneously vulnerable and safe.

It’s telling that the site’s popularity petered out only a few years later, its decline directly correlated with the rise of platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr (the closest relation to PostSecret, in both design aesthetic and emotional sensibility). The term ‘Web 2.0’ became popular around this time - the first in a long line of tech buzzwords that would almost immediately lose its meaning from overuse - but the moment itself was worth noticing. It represented one of the first major shifts in how we used the internet. No longer was it a place we visited for entertainment or information; the introduction of social platforms meant it was now a place where we lived and shared our lives.

Revolutionary as this was, it also transformed the way we understood privacy. Over the next ten years we saw private photos leaked, websites hacked, and state secrets revealed. On a personal level, we learned that nothing we posted online was ours and ours only. Everybody was vulnerable. Online commerce boomed. Advertisers found new ways of reaching their audiences and trust began to mean something else entirely.

It was alongside this evolution that the personal essay acquired newfound popularity: we still confess, but now we do it publicly. We no longer believe in true anonymity – we simply don’t trust it – so we blog. We write Facebook statuses. We’ve become used to talking about ourselves and each other and filtering the world through this lens, and in a world where advertising permeates everything, writing from a personal stance acts as a seal of authenticity. Which isn’t to say the anonymous confessional has died out completely: apps attempting to offer this are still being rolled out by hopeful grads in Silicon Valley, but they fail spectacularly on very fundamental levels. Whisper, which launched in 2012, purports to be anonymous but aggressively pushes people’s submissions to reporters (who can directly contact the poster) in an attempt to get media coverage. The form in its original use no longer exists because we now live in a world where there are more active Facebook users than there are Roman Catholics.

The form in its original use no longer exists because we now live in a world where there are more active Facebook users than there are Roman Catholics.

Despite the personal essay becoming a new dominant form, it isn’t necessarily the natural form. We still consider people to be ‘brave’ if they write about dealing with death, with depression, with divorce, with debt. These are hard experiences to share with strangers. You may not always be ready to deal with it, let alone write about it. You may be barely treading water. You may not want it to form a core part of your identity - you might not want to be labelled a ‘lesbian musician’ but simply a musician – yet we’ve created a world that suppresses admission unless you’re ready to go public, and that celebrates divulgences only so long as they’re triumphant. We demand hope even when it doesn’t come easy. But sometimes, all we want – and all we can be – is to be a different kind of human: fallible, multi-faceted, and private in our grief and hardship.

It’s against this backdrop that Declan Greene’s Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography is set. Unflinchingly honest, bleak as all hell and devastatingly funny, it follows the lives of two unremarkable, nameless middle-aged people dealing with hard situations. One’s a married IT technician, deeply unhappy, addicted to porn; the other’s a single mother, a nurse, in serious debt with a long list of bookmarked shopping sites. “They’re people we don’t often look at,” says Silo’s artistic director Sophie Roberts of the two characters. They’re people you might walk past in a mall and never give a second thought because they seem ordinary, because we already have preconceptions of what their lives are like, and because their lives don’t invoke hope.

The strength of the play is the tenderness with which Declan treats them. “He’s endowed them with a lot of intelligence,” Sophie comments. “They’re not stupid losers slopping around.” Rather than simply presenting them as entertainment, there’s real humanity here. It’s not hard to see how they’ve gotten this deep, and how each subsequent decision inevitably digs them deeper. They have agency, but you instinctively understand how tiring it is to keep pushing uphill. “They’re two people who have made some choices they’re now having to deal with, and they have really wonderful insights into their predicaments.”

It’s not hard to see how they’ve gotten this deep, and how each subsequent decision inevitably digs them deeper. They have agency, but you instinctively understand how tiring it is to keep pushing uphill.

None of their predicaments are new – they’re basic human problems like loneliness, love, and a frightening lack of control – but the challenges and conveniences of the digital era make them unique to this time. In one particularly heart-wrenching moment, the mother takes her teenage daughter and her friend to the mall, where they proceed to ditch her, as teenagers in tandem so often do. “I walked around,” she reports. “Nowhere in particular. Up and down escalators. I pretended to look in stores. I pretended to pick up things and be interested in them.”

“I wasn’t thirsty,” she continues, “but I bought a carrot, watermelon and ginseng smoothie from Tank Juice, which cost seven dollars.” She keeps walking. She keeps buying. “Then I gave up and sat in a toilet cubicle for an hour.” She spends that entire hour buying time, alone, in a shopping mall toilet, on her phone.

“I really identify, personally, with the financial anxiety of the script,” comments Sophie. “I think anyone who’s had an experience of debt or not having much money will identify with that character. That thing of finances spiralling out of control.” There’s also a more existential relatability that stems from the confessional-tone of the dialogue. It’s one of the more striking elements of the play: despite the specificities of the characters, so many of their decisions whittle down to vulnerabilities that are universally experienced and rarely voiced. We feel fat. We feel ugly. We feel boring and utterly alone.

“When people laugh with this script, it's almost an admission of something, which is quite interesting,” Sophie notes. “When you laugh at some of these terrible things they're confessing, you're sort of admitting something about yourself.” It essentially creates in the theatre the same digital panopticon we experience on social media, every action and interaction a reflection of ourselves.

“We currently live in a world that’s constantly attacking everybody’s self worth. There’s a whole lot of stuff around the kinds of versions of yourself you present online that’s sad and interesting. I think that’s something that’s starting to get a little out of control in the world we live in. The way you can curate your life in a way that really has nothing to do with truth, and how shit that makes everyone feel when everyone else in your life seems to have amazing lifestyles.”

This is hard regardless of your age, but particularly at that point when you’re meant to be at your peak. When Sophie first encountered the play two years ago, it was part of a workshop that Playmarket was running in collaboration with Playwriting Australia. “It stayed with me,” she says. “It’s the most interesting play I’ve read about that time in people’s lives, which I think has something to do with Declan and where he is in his life, and his perspective on it. It’s something to do with a younger person’s anxiety about being older, and being disappointed, and feeling like you’re not all the things that you thought were going to be. The anxiety is more acute.”

There’s clarity with distance. When you’re 20, the edges are sharper. You know what you want 30 to look like. Your definition of failure is clear-cut, and you’re brimming with all the possibilities that lie ahead. Then with each day, with each slightly missed step, you eke further away from those goalposts, rationalising each shift until it’s no longer possible or healthy to be honest in the same way.

Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography is unique because it denies its characters this safe recalibration, and because it gives a voice to a generation who were never truly part of the digital revolution, who never learned to share themselves online, whether anonymously or not. More than anything, it gives us something we’ve lost: the idea that we can still make mistakes and not learn from them, that we still don’t know what we’re doing with our lives and actually aren’t trying to figure it out, that we’re disappointed in ourselves, alone, scared. It gives us absolute, unedited, adult vulnerability, and all the liberating joy this can bring.

Silo Theatre's season of Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography

runs Thursday 18 June - Saturday 11 July

Tickets available here

Alongside this, we are hosting a one-night-only

live storytelling event I'm Feeling Lucky,

featuring tales from the internet's Wild West.

Wednesday 24 June

Tickets available here