Fakamālō atu Tangata‘eiki, Talau-mo-Kafoa Fakatava - Thank you Dad for inspiring a centenarian family legacy

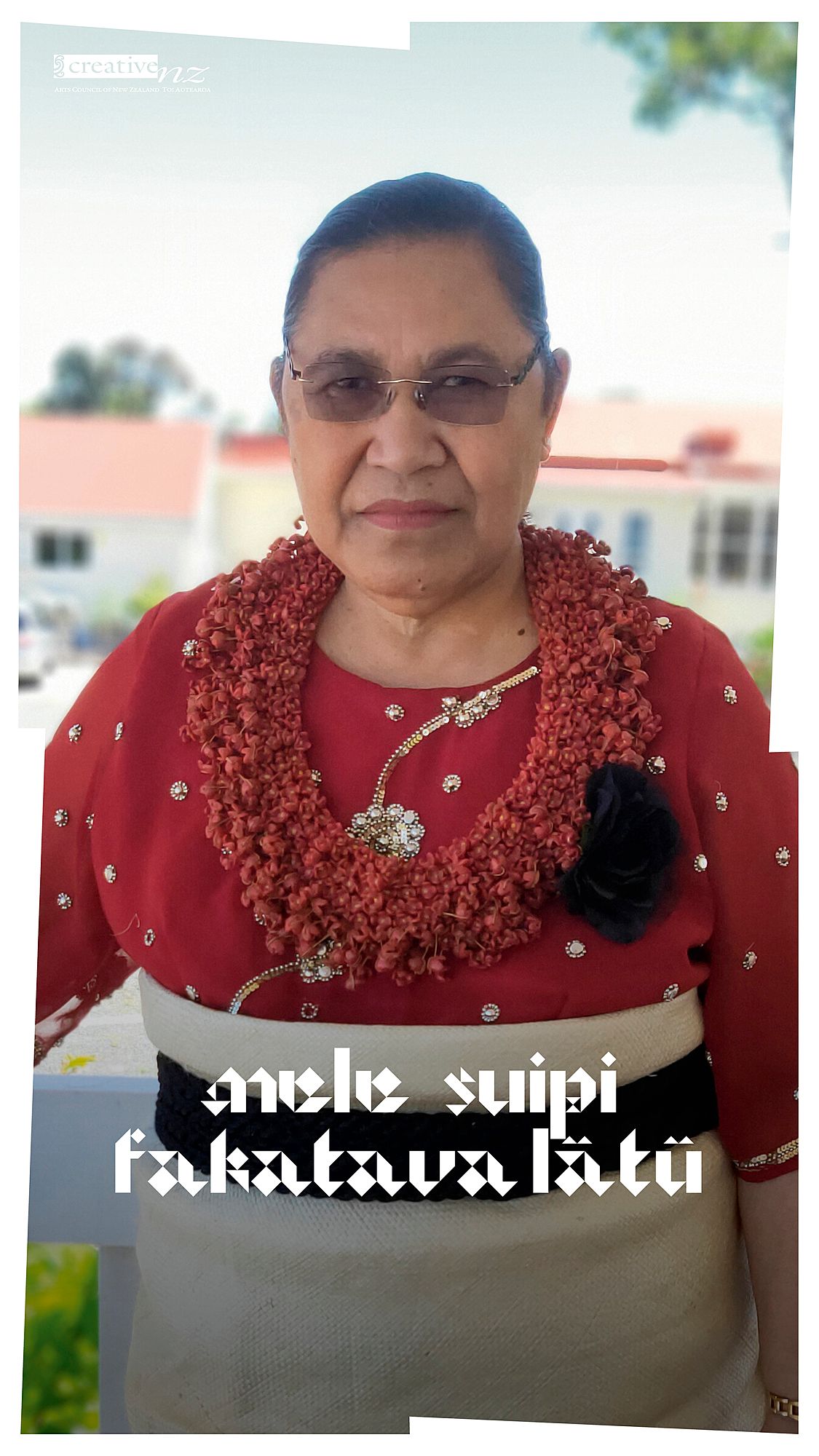

Born to a lineage of ancestral punake pedigree, Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū shares her journey embracing her familial legacy with conviction, great passion and commitment.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the ground-breaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

On Friday evening 25 June 2021, Lagi-Maama met with Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū and her lovely husband Manase Lātū Snr at Ōtāhuhu Food City, to invite her to contribute to the Pacific Arts Legacy Project. What we were gifted over five hours was laughter, tears, fellowship and access to an unedited truth that started inside over a shared meal and had spilled out into the carpark because we had talked right up to closing hours and hadn’t quite finished sharing yet! Our minds and hearts were overflowing with the emotional journey that Mele Suipi and Manase took us through. We are honoured that Mele Suipi has penned in this paper some of the talanoa she shared with us, giving readers the rare privilege of an intimate insight into her mind-heightening, heartening and inspiring journey as a punake.

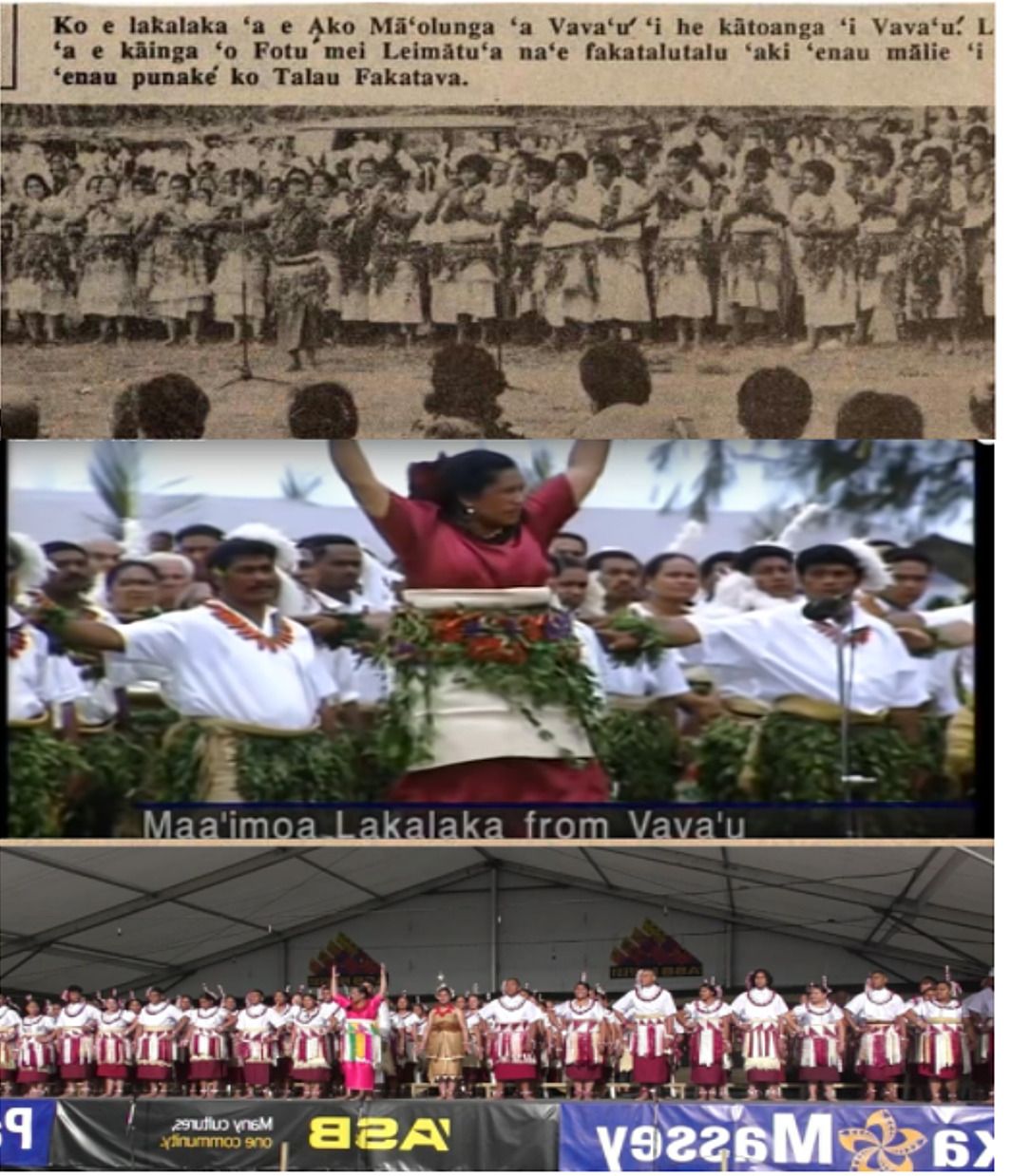

Top: Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū’s father, Talau-mo-Kafoa Fakatava, 1981. Centre: Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū, 1998. Bottom: Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū, 2018.

Being a punake is a family heritage

An explicit episodic autobiographical memory has been encoded, stored and continuing to resonate in my mind for several decades now. It is like a pinched nerve that occasionally yet inevitably puts me on a mental journey to recurring episodes of my golden, indeterminate 20s. This sojourn has a hypostatic union of both painful agony of regrets and sweetness of fatherly aspirations. The voyage takes me back again and again to conversations with my late father, Talau-mo-Kafoa Fakatava, about my potential capability to be a punake (a Tongan dance artist) and my silent antagonistic refusal. A fully credible Tongan punake should be able to combine poetry, music and choreography. One should be able to fatu ta‘anga (compose poetic lyrics) for the purpose of the faiva (dance), fakafasi (melodise the lyrics) and fakahaka (choreograph) the melodic lyrics.

A fully credible Tongan punake should be able to combine poetry, music and choreography.

I was born to a lineage of ancestral punake pedigree in the year of the Lord 1958. This heritage was originated and mapped at the national level by my grandfather, Melikiola Fakatava, in the early 1900s. He was a punake with a daring, legendary practice from the reigning era of King Tupou II of Tonga through to years of Queen Sālote Tupou III’s reign. Melikiola entrenched a renowned family history in this practice, instituted this capability in the Fakatava lineage, and consequently earned recognition from his gift of creativity and the labour of his hands. In a lakalaka (a combined male–female standing group dance) competition among Tongan punake during King Tupou II’s reign, Melikiola won a land trophy – ‘Api-ko-Tavahi in Fasi-moe-afi – now a family residence in Nuku‘alofa, and Kalau, a 50-acre island as a bush allotment adjacent to the district of ‘Eua, Tonga. He acquired much more land across the country, with most in Vava‘u where he resided in Leimātu‘a, which became the love of his life. He was blessed with eight children, my father the fifth. His burial ground is still there today, together with that of his wife, Sulifa Fusitu‘a Fakatava.

The period of 1979 to 1983 was momentous in my educational development and professional endowment. I launched and paddled my canoe into the academic ocean in pursuit of scholarly recognition. I landed at the shores of the University of the South Pacific in Suva, Fiji, where I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English and Sociology, and a Graduate Certificate in Education (BA, GCEd). That fully equipped me for my now 33 years in an education and teaching career. My Christian faith, at the very core of my being, was my main enabler; it anchored me, and I sheltered myself in its Power. My worldview therefore revolved around the underpinning postulation that lotu and ako (faith and education) were life facets worthy of my time and commitment. They became my twin towers, my rocks, and hope for a good future, so other engagements were for me mere distractions.

Like an Olympic torch relayed from one Olympian’s hand to another, so was our punake heritage relinquished by my grandfather to my willingly committed father

Unlike my late father, Talau-mo-Kafoa Fakatava; formal education was only a short-lived acquaintance for him, and higher education was non-existent in his life. He was just a simple, hands-on and loving father of eight, a loyal and fun-loving husband to my mother, Manusiu-he-Naua Maile Fakatava. Besides his family being the pride and joy of his life, his love and commitment to being a punake was of paramount importance to him. Like an Olympic torch relayed from one Olympian’s hand to another, so was our punake heritage relinquished by my grandfather to my willingly committed father and a daughter, Fakatouongo Kāvenga, when he passed. They became the next prominent legendary punake in our lineage. Talau-mo-Kafoa practiced from the reign of her majesty Queen Sālote Tupou III through to part of King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV’s reign. I grew up and witnessed the way my father, with deep passion, gave his all to work out this heritage for the good of our country. He regarded it as a fatongia (responsibility) to God and to the land of Tonga.

With this artistic breed evolving in the family, it was legitimate and logical for my father to ensure that the punake heritage was not destined to be a dying legacy. Could one blame him for gazing at his own children to jump on the bandwagon? I remember one time when my father conversed with me and, unexpectedly, he said, “Mele, I think you will be one among my children who would make a good punake. I can observe that when you speak at church.” He exhorted me, beat not around the bush, but appealed to me to grant him a chance to train me as one. It was an insaneous obscurity to me at the time, so much so that I didn’t allow a leeway in my prefrontal cortex for that proposition. Like a snowball's chance in hell, so was my father’s aspiration to me at that instant. Over and above, I remember time and time again when I returned home from university, my father requested that I get an inventory book and transcribe his compositions, as well as those of my grandfather. It was his desire to keep them as family heirlooms or treasury to be archived for use in the future. Again, like beating a dead horse, so was that too to my ears. Did I do any of this? No.

“Mele, I think you will be one among my children who would make a good punake. I can observe that when you speak at church.”

My allusion to a painful agony of regrets at the beginning of this story was about that. The genuine future-focused fatherly wisdom and aspirations were rejected by a then immature, unseeing-eyed daughter. Our outlooks about life engagements varied and, sadly, I thought that mine preceded his because I was more ako (educated) and lotu (faith). What a presumptuous folly, which only inflicted the walking wounded me with the ramifications of the sin of ignorance. I forfeited the infrequent golden fortuity to sit at the feet of the mighty and indulge in the unshackled wealth of the best compositions, melodies and choreography. A double-edged sword, one might say, but a could-be treasury of the best poetic lyrics and ta‘anga (compositions) of more than a century in my heritage, those of my grandfather’s and father’s, unscribbled away like sand through my fingertips. My father passed on in 1993, but the painful agony of regrets lived on and occasionally haunted me, especially when I became a punake in later years of my life. What counts, I should say though, is that punake as a family heritage was successfully relayed from the hand of our legendary grandfather to my father and aunt, over the years to sons and daughters, and now to grandchildren. The images below show my parents and a prospective undying family legacy with these punake already in the family lineage.

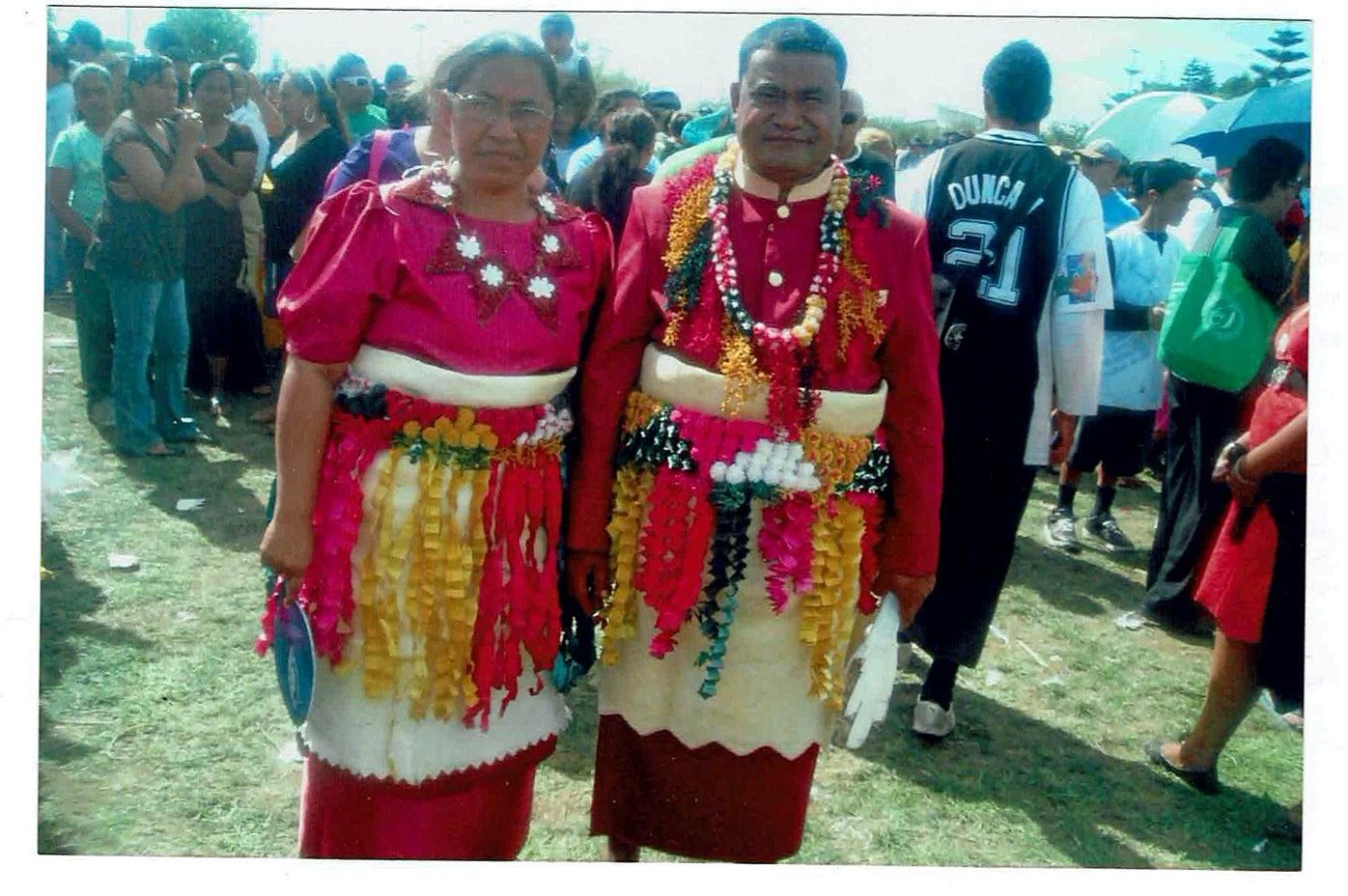

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū’s parents, Manusiu-he-Naua Maile Fakatava and Talau-mo-Kafoa Fakatava.

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū’s Fakatava Punake Family Legacy.

Although three of my talented punake cousins have already passed, and some of my siblings hardly practice the punake now, my younger brother, Metuliki Fakatava, and I still march onward as loyal punake soldiers of the lineage. We both carry the weight of our family heritage and take it to heart that we lay it safely in the hands of the next generations to carry forward.

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū and her younger brother, Metuliki Fakatava.

My punake journey was slow paced but incontestable

In 1994 I returned to Tonga with my husband, Manase Lātū, and our three lovely and beautiful daughters, ‘Anahina, ‘Akanesi and Manusiu. Four years prior, we had resided in Perth, Australia, pursuing both our master’s degrees, his in Business Administration and mine in Applied Linguistics. My employer, the Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga, stationed me to be a deputy principal at Tupou High School, Vaolōlōa Branch. For two consecutive years, my family and I offered our service there.

At our school anniversary celebration that year, we were expected to perform a faiva (traditional dance), which is an expected form of entertainment in any Tongan cultural celebration. We needed a punake to do that, but at the same time we had obligations to the punake. Traditionally, we express gratitude to the punake at the end of the occasion by giving back traditional koloa such as fine mats or tapa and/or money. We did not have allocations for such at school at the time, so I decided to take a leap of faith and do it myself.

Traditionally, we express gratitude to the punake at the end of the occasion by giving back traditional koloa such as fine mats or tapa and/or money.

Surprisingly, I could compose verses of the ta‘anga (compositions) to some already existing melodies awakened in my mind. I could hear those familiar ones, and they were none other than those of my grandfather and father. It was amazing! However, after the celebration, I was as happy as a clam for a job done, and that I had done my first mā‘ulu‘ulu (sitting dance). Did I see myself as a punake after that? Was a desire to be one aggravated? Not a bit. I was just simply thrilled and pleased that an obligation was rendered, done and dusted. My perception was that I was making the hedge, and standing in the gap to complete a responsibility. As that year drew to an end, so was the first time of my being a punake written as part of its history.

The fiscal year 1995 gave me a second bite at the cherry. Another normal school year started off, but not long after that two different church congregations approached me to be their punake for an annual youth dance competition in the church. Apparently, they had been spectators at my school dance performance the year before, and they were also aware of my punake family heritage. With vested confidence in my capability, they pursued me to task it for them. Again, I wasn’t sure how I did it, now two group dances at one time, but I did it again. Did that experience convince me that I was a punake then? Not really. At least it was a boost for my confidence, skills and tenacity in the punake practice. I was a bit better at composing, with melodies, and choreography, but my interest had not even been sparked. It didn’t even spring to mind that perhaps I was living out what my late father aspired for me to do. It was like another day in the office, and I was exhilarated the stress was over.

It didn’t even spring to mind that perhaps I was living out what my late father aspired for me to do.

I landed in the district of Vava‘u with my family in 1996. Stationed to be the principal of Mailefihi/Siu‘ilikutapu College, a co-ed high school also run by the Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga, my family and I pursued that calling. Besides being blessed with a son early that year, Manase Lātū Junior, I was simply overjoyed to return to my Bethlehem – Vava‘u – because I was born there. It was also in Vava‘u that my grandfather intensified his punake practice and commenced the Fakatava heritage in faiva, and my father continued the same. It was great to be back home!

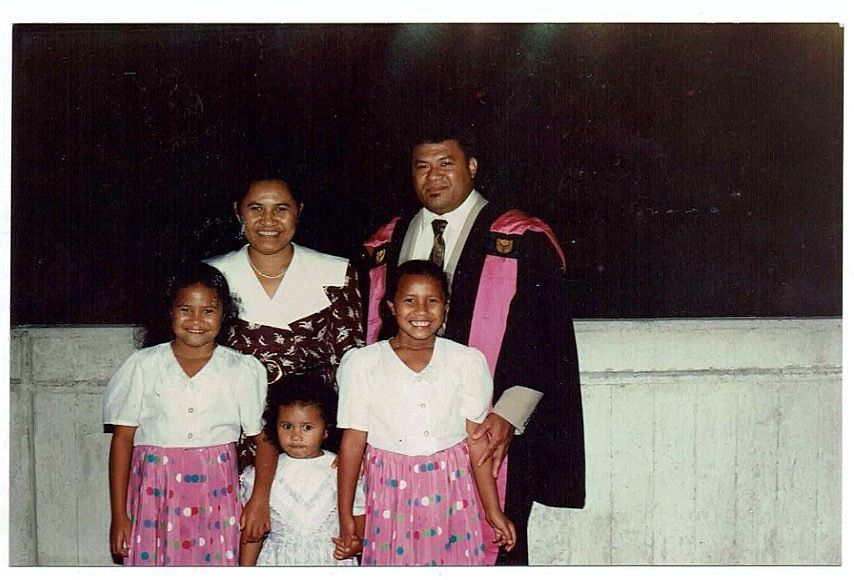

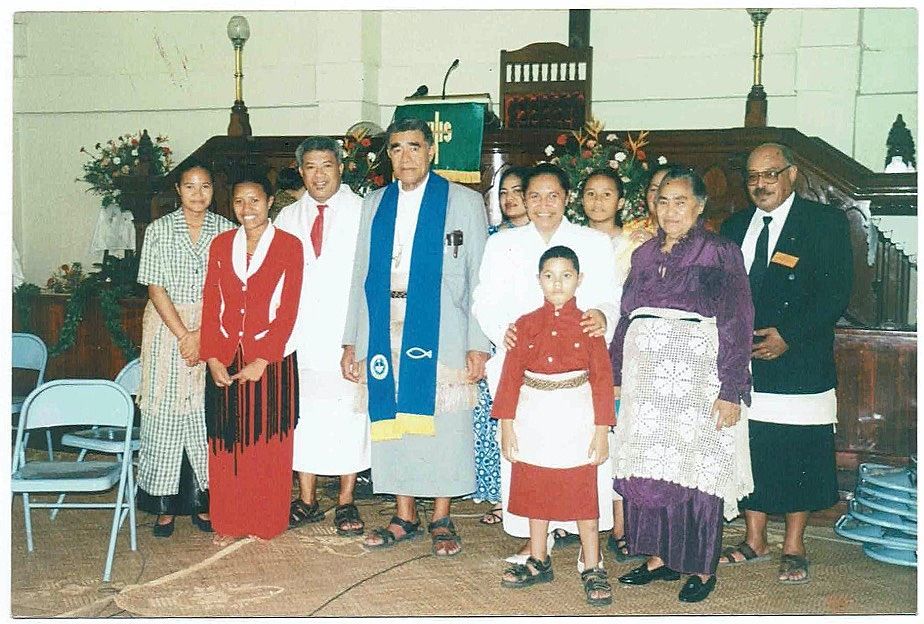

Our school Golden Jubilee was to be celebrated in June 1997, and it was not coincidental that the Free Wesleyan Church conference was also scheduled to be at Vava‘u at the same time. A milestone happened to me that year. I was accepted to be a probationary church minister at that conference, and, as shown in the photo of my family with Reverend Dr ‘Alifeleti Mone, I was ordained as a church minister four years later, in 2001.

Mele Suipi Fakatava and Manase Lātū with their children, ‘Anahina, Manusiu and ‘Akanesi Lātū, in Perth, Australia, in 1993.

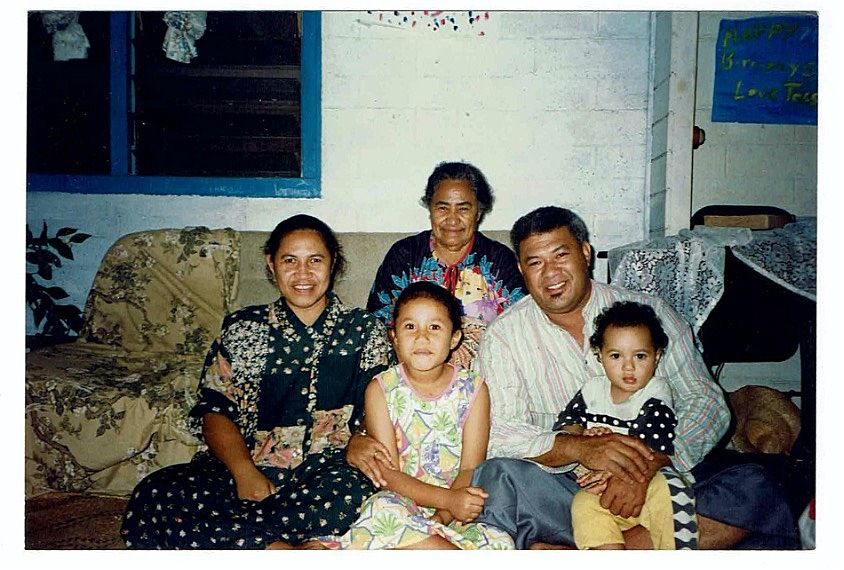

Back: Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū’s mother, Manusiu-he-Naua Maile Fakatava. Front, left to right: Mele Suipi Fakatava, Manusiu, Manase Snr and Manase Lātū Jnr, Vava‘u, Tonga, 1998.

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū and her family with President, Rev. Dr ‘Alifeleti Mone (with Clergy blue stole), and members of the Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga, in Nuku‘alofa, 2001.

For the celebration, the King of Tonga, King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV, was the guest of honour. His daughter, Her Royal Highness (HRH) Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita, was among the royalty to honour the celebration. Similar to 1995, we were expected to perform a dance, but with the same circumstances, it was decided then for me to be the punake again. Dissimilar to 1995, though, there were more students to be trained (about 600), and more people to gaze and be entertained. Above and beyond, His Majesty, the summit of the whole land, was to be present and to be majestically entertained. That was an unimaginable stress! I had sleepless nights over my capability to do a faiva dignified enough for the King. That was absolutely worrying, but in the end I succeeded. I was not too thrilled with the quality of the execution, but thrilled that another commitment was accomplished and penned off from my calendar.

King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV was born on 4 July 1918. He turned 80 in the upcoming year, 1998. The country therefore orchestrated a national majestic celebration for his birthday. It was to be top notch, a one of a kind for all Tongans inland and abroad. To be able to attend was a rarity of great honour because such a celebration was almost entirely reserved for the Royal family, aristocrats, nobility, ministers of the Crown, dignitaries, the blue blooded and privileged elites. It was a funny dream for a commoner at the lowest strata of the hierarchy to even anticipate being invited.

It was a funny dream for a commoner at the lowest strata of the hierarchy to even anticipate being invited.

HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita and her husband, Lord Tuita, were residing in Vava‘u at the time because Lord Tuita was the Governor. She desired that a lakalaka (a combined male–female standing group dance) be learned by villages of Vava‘u and to be performed at the King’s birthday celebration. The common practice was for only one village in Vava‘u to do that for the whole district in any national celebration of that calibre. The punake in the district were on the lookout for a tap on the shoulder as to who would have the honour. To my gripping, breath-taking flabbergast, HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita called me to her residence and confided to me about her wish. She wanted me to be the punake of that lakalaka. The fact that she believed in me took me to walk on cloud nine, but soon after, my astonishment enslaved me to a sense of reality that turned to a deep nerve-wracking shock. I had never done any lakalaka before, I had only done mā‘ulu‘ulu (sitting dance). Further, to step onto a traditionally male-dominated turf at a national event of such magnitude, that was exceptionally rare. Far and above, a sense of inadequacy overtook everyone. How could I be majestic enough in all that was required of a punake to abundantly dignify and encapsulate the paramount of the Kingdom of Tonga, King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV? Yet despite those profusions inhabiting my whole being for a week or two, refusing HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita’s wish was a pathway I could not bring myself to tread.

It was from that spiritual, emotional, and intellectual stand-point that I started to compose the ta‘anga (compositions) for the lakalaka.

Taking my sanctuary under the wings of the Dove, I set about shouldering what was for me at the time the almost impossible undertaking. Foremost, I implored HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita to enrich me with a guide on what to contextualise in the composition in order to do justice for the abundance of His Majesty. I could barely say anything at all to get me off the ground. Instead, she gave me a biography of the King, The King of Tonga – King Tāufa‘āhau Tupou IV, written by Nelson Eustis, which I buried my head in twice in a very short period of time before composing. It was an overwhelming top-of-the-world sightseeing into a life so full and colourful with natural gifts and endowments, personal achievements and establishments, and unconditional patriotic love and services. Far above that, my heart was won and filled to the brim with admiration, gratitude, and love for His Majesty. His Majesty was an instrumental embodiment of blessings from upon High for the Kingdom of Tonga.

It was from that spiritual, emotional, and intellectual stand-point that I started to compose the ta‘anga (compositions) for the lakalaka. My being an educator and church minister at the time rooted and drove my purpose and endeavour as a punake at that occasion. I wanted to be a voice to tell the people of the land at all levels what His Majesty had done in building and developing our land to modern Tonga. I desperately wanted to sing his praises unreservedly and grant him acknowledgements as deserved. Therefore, breaking the traditional use of metaphorical and symbolic language allusions called heliaki, I composed 13 verses of ta‘anga in direct, literal, layman’s language for everyone’s comprehension and appreciation. When I submitted the ta‘anga to HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita , her teary emotional response indicated that I was on the right path. From memory, I heard her saying (I paraphrase) that since growing up she has never heard a punake alluding to those achievements of her father, His Majesty. Wow, one check-point done well!

My being an educator and church minister at the time rooted and drove my purpose and endeavour as a punake at that occasion.

HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita named our lakalaka the ‘Maa‘imoa’. It took us literally a bit more than a month to learn and practice the lakalaka in Vava‘u before we set out to Nuku‘alofa, Tongatapu, to perform at the high-class celebration. There were about 300 dancers alone in the group and then about 300 langitu‘a (the singers singing from the back to support the dancers). Those participants were from different villages, churches and organisations, and were nobles, chiefs, church ministers, commoners and different generations. Anyone was welcome to join. HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita and her husband, Lord Tuita, the Governor of Vava‘u, also joined. Their eldest daughter, Honourable Lupepau‘u Tuita, was the vāhenga for women, and Honourable Fulivai, a noble, the vāhenga for men (vāhenga are the two most dignified positions, right in the centre of the first row, reserved only for royalty, chiefs or nobles). We landed in Nuku‘alofa a few days before the celebration, and many more Vava‘u patriots joined us.

The special, majestic yet nerve-wracking day for me at last arrived. I led the Maa‘imoato Pangai Lahi (a field adjacent to the palace, reserved as a venue only for rare royal functions), and into the presence of His Majesty, the royalty, nobles and chiefs, leaders of the land, and the dignitaries from abroad. There were about 800 or more Vava‘u patriots performing with their best, far above and beyond with the fatafata māfana (warm heart). We moved the crowd, not only by the sheer magnitude of our numbers and a new face of female punake, but by the mālie (skillful execution) and māfana (warmth) of the performance. HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita summed it up quite well: “I love dancing. I have been dancing since I was a little child, informally. Although it wasn’t easy because 13 verses in a lakalaka is a pretty long lakalaka. But just by performing that ta‘anga was a spiritual thing for me. Just hearing the tremendous roar of singing from behind me was something I never experienced before. It was a different māfana that I experienced that day”(an excerpt from the documentary Haka He Langi Kuo Tau). I did it. Yes, thank God, I did it!

"just by performing that ta‘anga was a spiritual thing for me. Just hearing the tremendous roar of singing from behind me was something I never experienced before."

A screenshot from the Maa‘imoa lakalaka performance at Pangai on 4 July 1988.

A screenshot of the multitudes of people present on the day.

A screenshot – Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū, punake of the Maa‘imoa lakalaka performance at Pangai, 4 July 1988, which was also featured in the documentary Haka He Langi Kuo Tau.

That was a masterpiece for me! Not in my wildest dreams did I ever imagine that a day and experience of such distinctiveness would happen in my life. But it was not just the mere episodic experiences on the day that were encoded in the memory and history. There were some major ground-breaking milestones accomplished for me that day.

First, the most credible recognition of a person to be a punake in Tonga is when one performs a faiva in front of the King or Queen of the land, the elites and leaders of the country, and people of the land at home and abroad. It happened to me that day! Without any bestowment of a certificate, a medal or a trophy, my recognition as a punake was encoded in the history and in the hearts and minds of Tongans present on that day and across the world. It was a silent endorsement of my capability, credible to standard, to be regarded as a practicing punake of Tonga. I procured that entitlement on that day.

Without any bestowment of a certificate, a medal or a trophy, my recognition as a punake was encoded in the history and in the hearts and minds of Tongans present on that day and across the world.

Further, on a more personal level, I finally accepted and sanctioned myself to be a punake on that day. Punake was no longer a hedge to be stood in the gap, an obligation to be done and dusted, or simply a bit of history to be penned. The future-focused wisdom and aspiration of my late father, Talau-mo-Kafoa Fakatava, was realised that day. Finally, I embraced it with conviction, great passion, and commitment. It was on that day that my family heritage and legacy of punake was successfully placed in my hand in his absence and without being contested!

I thank God for HRH Princess Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita. Her faith and confidence in me were instrumental in my making to be a punake. She will always hold a special place in my heart. Fakafeta‘i ē fakakoloa, Pilinisesi Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu Tuita!

Twenty-seven years later

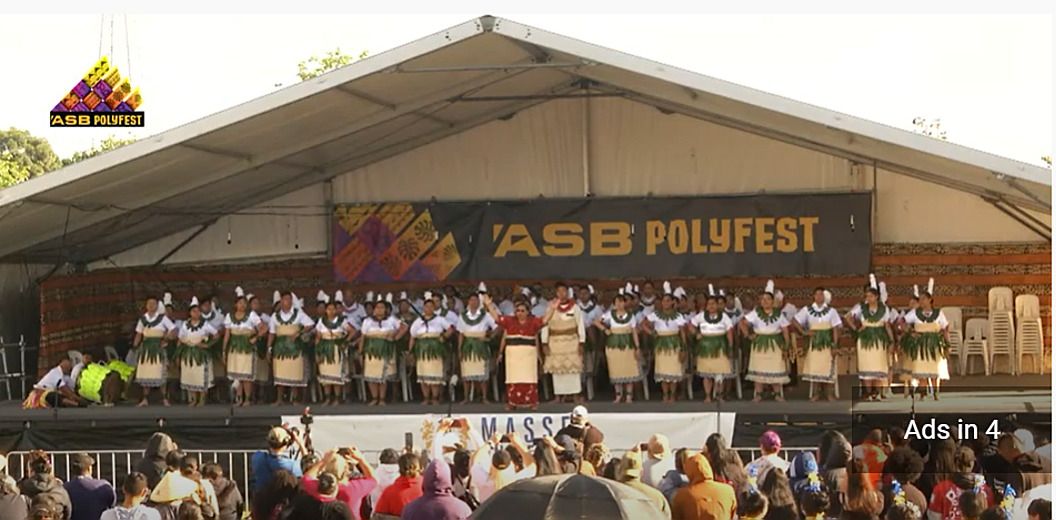

It is 27 years now since the performance of my first faiva in 1994. I am still head-on strong being a fully credible Tongan punake. Wholeheartedly, I still uphold my family heritage and legacy. Beyond that, I see myself as a custodian of our Tongan faiva. Through practice and involvement at Polyfest and other traditional occasions with faiva, through adjudicating at Polyfest and other faiva competitions, and through training young people at personal levels, I see myself as a voice in upholding the traditions of our Tongan faiva and culture. That is my commitment at the national level. Being a punake for me now is a service I render to my family, to God and Tonga, my inheritance!

Fakamālō lahi atu Tangata‘eiki, Talau-mo-Kafoa Fakatava, he tui, he fakalotolahi, mo e falala na‘a ke fai mai kiate aú! Dad, thank you for believing in me, thank you for inspiring me, thank you for your confidence in me!

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū, punake for Tāmaki College mā‘ulu‘ulu at Polyfest 2018.

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū, punake for Tāmaki College mā‘ulu‘ulu at Polyfest 2021, winner of the mā‘ulu‘ulu category (click link to view the performance).

My warrior

‘Oku ‘ikai ha To‘a ‘e tu‘u tokotaha is a Tongan idiomatic saying that means no warrior can make or do it alone. A warrior, acknowledged for unique bravery, needs the knowledge, skills, support, confidence, care, trust, love, prayers (and the list goes on) from others. Without these, a warrior cannot make it and is bound not to succeed. For me, one core trait of a real warrior is unselfishness, having unconditional compassion, concern and love for others.

My ‘warrior’ husband, Manase Lātū Snr.

I regard myself as a punake because I can compose, do melodies and choreography, and execute training and practice. Those make me a great punake warrior. Right? Perhaps undeniably so. But in my punake journey, I found I needed much more than those strands. I needed courage, exhortation and support that I personally did not have, in order to get me there. I was self-conscious as a woman, it was scary, and inferiority was a big deal for me. As a mother with children to look after and responsibilities, I needed understanding, sacrifices and unselfish unconditional love. I found all that in one incredibly amazing and unselfish (handsome, too) person who stood behind the scenes and willingly gave all those to me. He is my beloved husband and best friend, Manase Lātū Snr. In all honesty, he is second to God, for without him, I would not have the courage and focus to take the punake journey. My husband has the traits of a warrior and he duly deserves acknowledgment in my storytelling here. I am truly convinced he is a brave warrior. He was not afraid to grant me the stage to shine while he was behind, the front seat while he sat at the back, and while I was away doing practice, he was at home cooking and doing homework with the kids. His timeless response every time I asked him to pursue a dream or a call was, “I am not gifted or wired like you. I don’t have what you have from God, so I cannot stand in the way but only support. You share your gift.” It took a brave warrior to beget another. Manase is that warrior to me. Mālō ‘aupito Manase!

I was self-conscious as a woman, it was scary, and inferiority was a big deal for me.

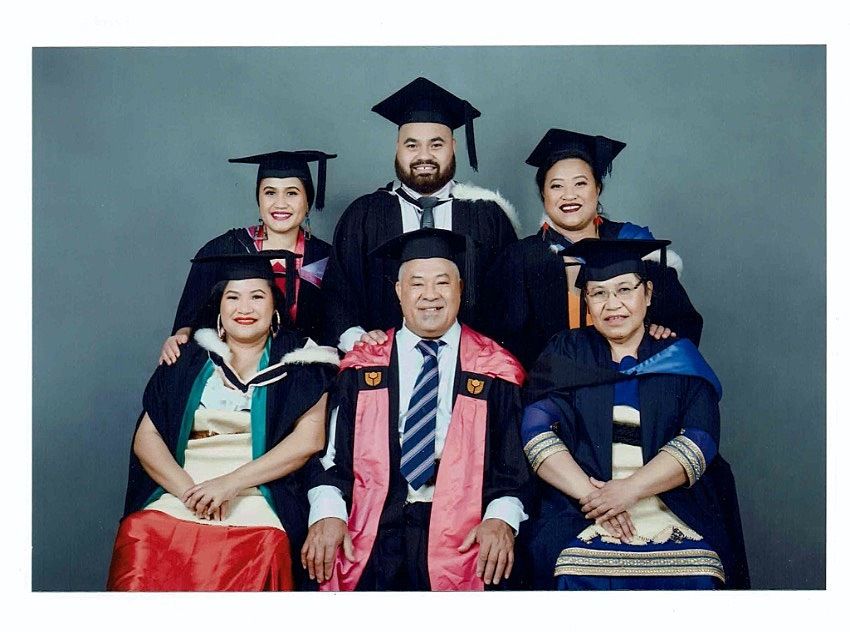

And last but not least, I acknowledge and thank my four lovely children – ‘Anahina, ‘Akanesi, Manusiu and Manase Jnr – for their understanding and support in our journey for me to be a punake. And for the rest of my family, Taipaleti Malolo, Solomone, Ella, and my grandson, ‘Ofa Moala Jnr, thank you all. My success is ours. To God be the Glory!

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū’s family. Top, left to right: Manusiu, Manase Lātū Jnr and ‘Akanesi Lātū Moala. Bottom, left to right: ‘Anahina, Manase Snr and Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū.

Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū’s extended family. Top, left to right: Solomone and ‘Akanesi Lātū Moala, Manase Lātū Jnr, Ella Ewen and Manusiu Lātū. Bottom, left to right: ‘Ofa Moala Jnr, ‘Anahina, Manase Snr and Mele Suipi Fakatava Lātū, Taipaleti Malolo.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy.

Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photo: Manusiu Lātū