Fitting the Description: Understanding Anti-blackness and Black Youth

Black youth are just as at risk of anti-black violence and racism as adults, writes Adele Norris.

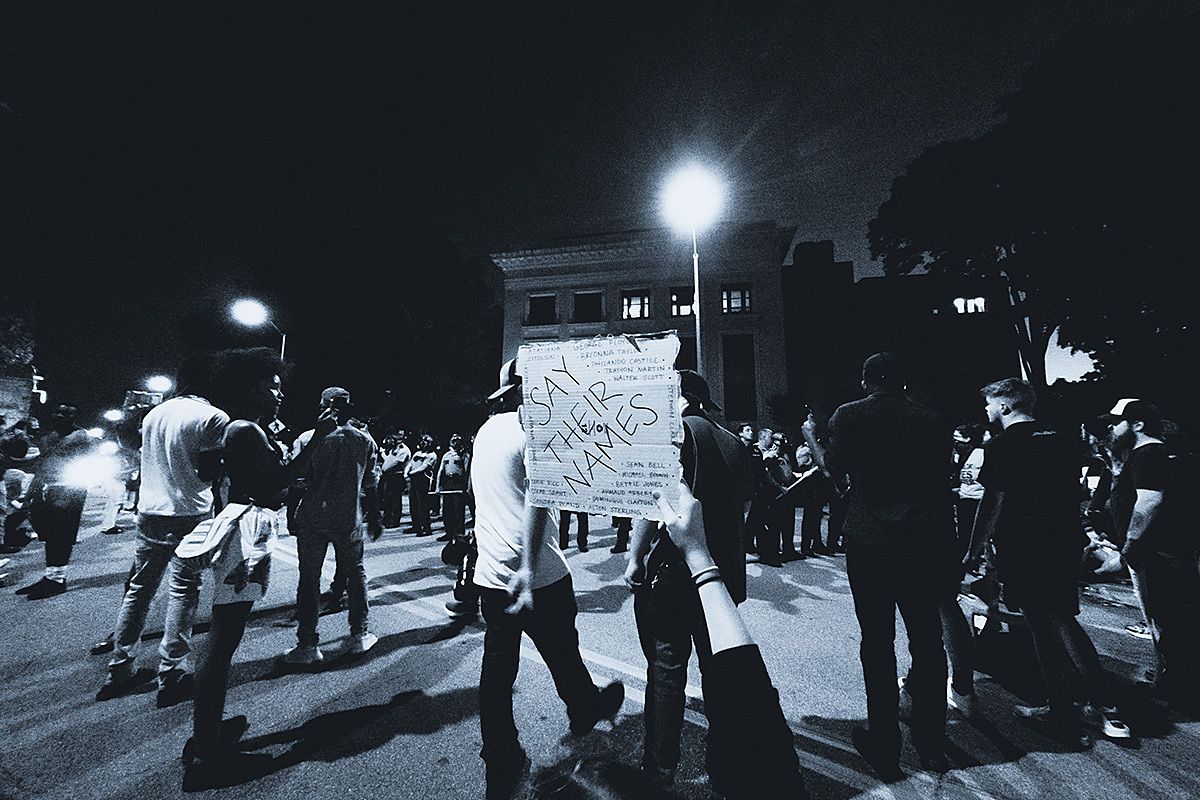

One week after the Black Lives Matter protests erupted in response to the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis law enforcement on 25 May, I had two conversations, only hours apart, that illustrated the reality of Black life few people understand. At my local café in Hamilton, New Zealand, my white male server, who is also an acquaintance of mine, immediately approached me with the words: "I haven't watched the news in a few days. It's too stressful." His comments came a few hours after my morning phone conversation with my Black-American friend, a mother of three. During the conversation my friend informed me that she’d recently purchased an array of different video recording apps and technology for her family. They were to be used at home, in the car, at work, when going out for a morning jog, in case they ‘fit the description’, and video evidence was needed to prove their innocence, that they’re simply trying to live their lives.

Those three words ‘fit the description’ reflect the daily reality of Black life. My friend sees her three children under the age of 12 as being as vulnerable to police violence as herself and her husband. Her concerns are a glimpse inside the burden that Black people in the US and over the world carry every day. That burden doesn’t go away by turning off the news. Black parents arming their children with recording devices is as normal as packing a school lunch, even when we know videos may not be enough to save our lives. Black people equipping themselves with recording devices has become a norm that is a byproduct of anti-Black racism that sees Black people in constant fear for their lives.

Visibility of police killings of unarmed Black Americans is only the tip of anti-Black racism

Hyper-visualised examples of anti-Blackness and the prevailing lack of value of Black life is not new and distinctive, but connected to a long history of abuse at the hands of the state. It is essential to distinguish between violent murders of unarmed Black men by law enforcement, and the racist systems that allow such atrocities to occur with little accountability. Racism is an inherent feature in the relationship between state institutions and Black people. Recognising that this racism is rooted in anti-Blackness, established through slavery and colonialism (and applies to Indigenous bodies as well) should be central to an anti-racist movement.

Those three words ‘fit the description’ reflect the daily reality of Black life

Black youth experiences with state violence aren't different or less brutal from the experiences of many Black adults. Understanding the Black Lives Matter movement requires us to move beyond the criminal justice system and include the experiences of Black youth. Since the beginning of the protests about the killing of George Floyd, videos have surfaced of Black teens being accosted by law enforcement. On 15 June 2020, a Georgia police officer drew his handgun on a group of Black teens because they 'fit the description' of men suspected to be in possession of a gun. More than 30 neighbours stopped and pleaded with the officer to lower his weapon. Two days later, two Black teens, aged 15 and 13, were violently handcuffed and placed in a patrol car for 'jaywalking' in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Black youth proximity to state violence

The tragic experiences of these Black teens is not isolated or random. Black youth have always been particularly vulnerable in all ages, genders, sexual orientations, educational attainment and social classes.

On 26 February 2020, videos began circulating on social media of Kaia Rolle, a 6-year-old Black girl, being handcuffed by an Orlando police officer and put into a patrol car. This incident took place a couple of weeks after the removal of 6-year-old Nadia King by a Jacksonville, Florida, sheriff's deputy, from Love Grove Elementary School on 4 February 2020. The school informed the officer that Nadia was "a threat to herself and others" and was "out of control" and, thus, instructed her to take Nadia to a mental institution without her mother's consent. Their schools’ actions fall under the controversial Florida law known as the Baker Act, but the girls’ Black skin made them vulnerable under such legislation. As Black girls, Kaia and Nadia fell outside the boundaries of protection in the educational, criminal justice and healthcare systems.

Similarly, Mike Brown, an 18-year-old Black male killed by a Ferguson, Missouri, police officer, was stopped under the auspices of Ferguson Municipal Code Section 44-344, “Manner of walking along roadway”, which is essentially an appeal to use the sidewalk. This law can be used, and is frequently abused, by police officers to question Black people under the guise of their ‘jaywalking’.

Black children, in the eyes of society, are viewed as less innocent, troublesome, and more adult-like

Educational attainment, which is often promoted by those who ascribe to respectability politics as a viable response to systemic racism, does not protect Black youth and young adults. Jaylan Butler, a 19-year-old freshman at Eastern Illinois University, was accosted by six police officers when he and his teammates travelled to a swim competition in South Dakota in February 2019. When Jaylan exited the bus with his teammates at a rest stop, he was singled out by officers as 'fitting the description' of a suspect at large in the area. Jaylan's Black skin can have been the only factor: Why would a predominantly white swim team willingly host a suspect at large, especially a Black one? One officer jammed a knee into Jaylan's neck while another uttered the command: "If you keep moving, I'm going to blow your f---ing head off," according to the lawsuit filed in the United States.

Continuity of state violence against the most vulnerable Black bodies

Fourteen-year-old George Stinney Jr remains the youngest person in the US to receive the death penalty by electric chair, in 1944. An all-white jury took less than 10 minutes to convict George, a Black teenage boy, for the murder of two white girls in Alcolu, South Carolina. George's family never saw him again during his 81-day confinement at a prison. In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched and tied to the back of a pickup truck by a mob of white men after Till was accused of offending a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, by whistling at her. The men never faced criminal charges, and Carolyn, right before her death, confessed to lying.'

Black children, in the eyes of society, are viewed as less innocent, troublesome, and more adult-like. Coupled with anti-Black hatred, the deviant label assigned to Black youth denies their youth and humanity. As a result, Black youth have always had vastly different experiences with state institutions, such as the police, than their white counterparts. Senseless deaths and wrongful convictions of Black children speak to how easily the state can erase Black life without recourse. In 2014, 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot and killed by Timothy Loehmann of the Cleveland, Ohio, Police Department while playing at a park with a water gun. In 2010, seven-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones, of Detroit, was sleeping when the police raided her grandmother's home in the middle of the night and shot her in the head. In 2017, police officer Roy Oliver fired into a carful of teenagers in Dallas, Texas, killing 15-year-old Jordan Edwards.

While these young Black lives ended tragically, those who survive extreme police encounters are left traumatised. In 2019, Chicago police raided a home during a four-year-old's birthday party, smashed the cake and poured peroxide over the gifts. Dejerria Becton, at the age of 15, was forcefully grabbed and slammed to the ground by police officer Eric Casebold at a 2015 pool party in McKinney, Texas.

Black youth and the white imaginary

These examples extend the conversation raised by Ava DuVernay's Netflix seriesWhen they See US. The series tells the story of the harrowing experiences of five Black teenage boys who, in 1989, were accused, convicted and sentenced to prison for the rape of a white woman in Central Park, New York City, without any evidence connecting them to the crime. D L Hughley, a comedian and radio personality, stated in response to the series, "The most dangerous place for Black people to live is in white people's imagination." Hughley defined the white imagination as the place where the Black boys had ceased being children and became monsters. The teenagers' criminal convictions propelled the careers of almost all who were connected. Linda Fairstein, the prosecutor, became a bestselling author. Donald Trump, who campaigned heavily for the teens to receive the death penalty, became President of the United States.

Black people are perceived as deviant without question

D L Hughley's poignant sentiments illustrate the nature of the white imaginary to place limits upon Black humanity. It is a force that has continuously perpetuated many (un)freedoms experienced by Black people because, inside this warped belief, Black people are perceived as deviant without question. Absent from the white imaginary, Hughley argues, is that Black people work hard, love their families, and are honest and educated. In the case of Black children, too often, anti-Black hatred trumps their humanity and innocence, thus becoming the driving force that leads to early and brutal encounters with the criminal justice system.

The white imaginary is wedded to Black suffering in complex ways reinforced daily through social institutions such as schools, hospitals, the criminal justice system and social services. An anti-racist social movement must centre anti-Blackness by interrogating the relationship between racist systems and Black suffering, anguish and trauma, especially when 'fitting the description' can mean your life. Bringing Black youth into the conversation of state violence adds another dimension to the reality of anti-Black racism and Black suffering. Centring on the experiences and voices of Black youth is critical to understanding how anti-Black racism is expressed today and the steps needed to protect Black bodies, especially the most vulnerable.