For Marjorie: Experiencing the 20th Century Through The Mental Health System

Elizabeth Beattie on her grandmother, and 60 years of shifting mental health attitudes

From early in my childhood, I knew my Nana wasn’t like other Nanas. She never did baking with us on weekends, or read stories to us, and she wasn’t allowed to look after us on her own.

Instead, she would get up in a crowded Dunedin cafe and burst unexpectedly into song, her favourite choice being a quivering rendition of ‘Pokarekare Ana’. She would give impromptu speeches at public gatherings, and determinedly insert herself into formal photos of church elders. She once rang up a radio station and convinced the hosts that she was a former gold medalist in the Olympics. Once live on air, they only twigged something was amiss when she revealed to them live on air that she was well into in her seventies, and that she had a trapeze in her bedroom.

This can sound like an accumulation of sweet and innocuous memories. Kids’ literature makes eccentric family members into a source of wonder, wisdom and delight, and smoothes the edges off the surprises. In fact, growing up with someone who experiences severe mental health issues can be unsettling for a child. Working to form your own nascent sense of the world around you, their reality is competing with others for your attention. You learn to fret about what suspicions and anxieties lurk beneath seemingly innocuous words, what paranoia or oncoming change of mood is often buried under a seemingly innocent phrase.

Looking back, I can see that her reality was often a confusing and confronting place. If the unexpected wasn’t fun for us, it certainly wasn’t fun for her.

My younger sister, Hannah, remained a quiet spectator of Nana’s highs and lows. Faced with conflict or tension, she tended to withdraw – but she remembers acutely the sense of confusion.

“The truth became a very foggy concept throughout my childhood: there were always demons living in the corner, or secret conspiracies or men trying to break in. As I got older, I began to realise that a lot of my anxieties were the product of someone else’s mental illness, but at the time I lived in a heady excess of fear and confusion, similar to Nana’s I suppose.

I used to wonder what it was like in her world,” she says.

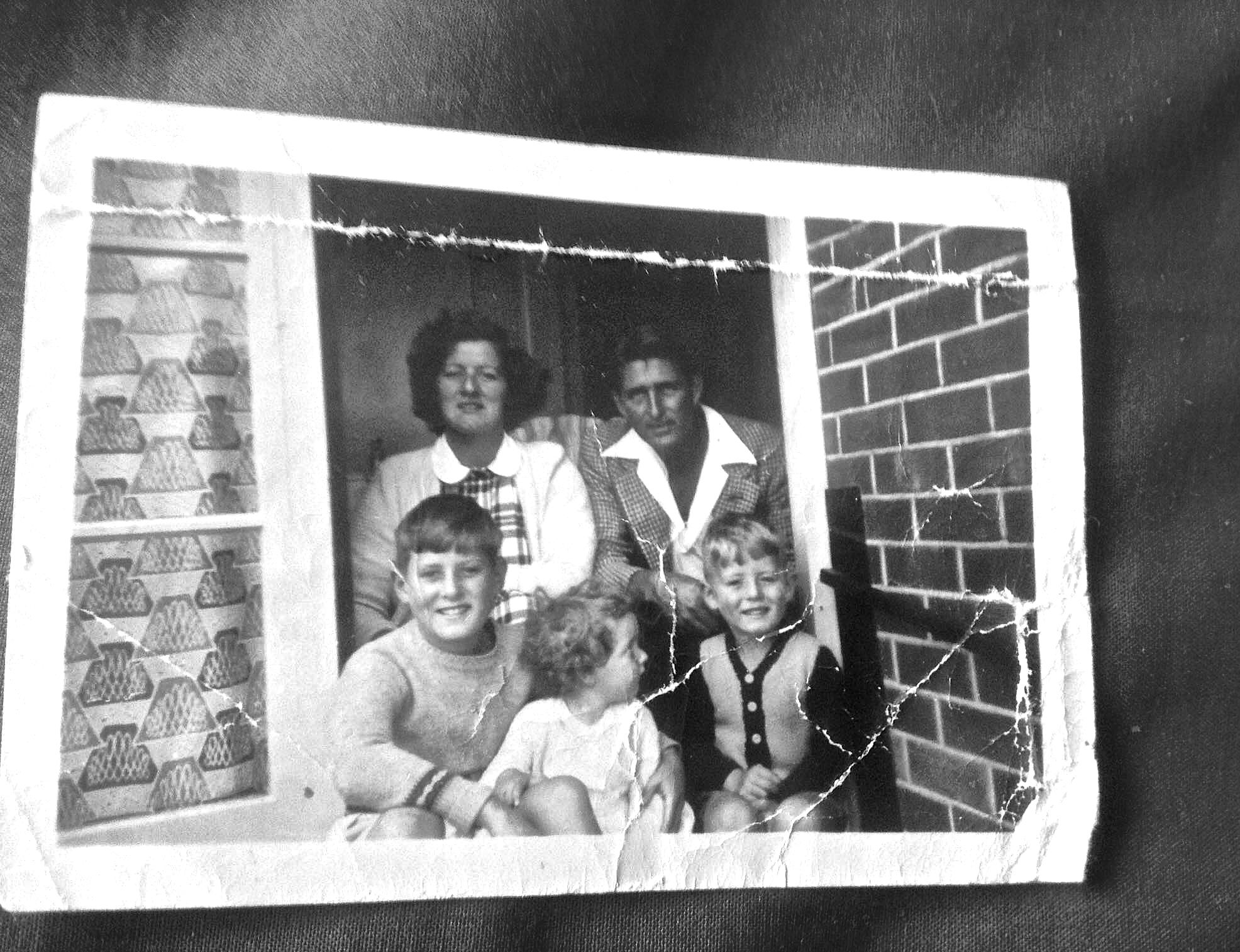

Marjorie Lusty was born in Invercargill on March 12, 1929. She was part of a large, Depression-era family. Life was brutal, and the vistas for what women could expect to achieve were limited. She arrived into a time with little understanding of what mental illness is, and only the most basic – but coercive - treatment offerings.

Before Nana was 17, she had married her husband, and as was expected, she became a homemaker and a mother.

How long, or even if, she struggled privately without anyone else seeing anything I can never know. From our family history, I know that things truly began deteriorating after she lost her baby, David Russell, who died of a heart condition a few days after he was born. Nana became despondent. She stopped eating and talking, and was soon admitted to Seacliff Asylum, near Dunedin, the same hospital where Janet Frame was misdiagnosed with schizophrenia and would later describe in her autobiography:

“The six weeks I spent at Seacliff hospital in a world I’d never known among people whose existences I never thought possible became for me a concentrated course in the horrors of insanity and the dwelling-place of those judged insane, separating me forever from the former acceptable realities and assurances of everyday life….Many patients confined in other wards of Seacliff had no name, only a nickname, no past, no future, only an imprisoned Now, an eternal Is-Land without its accompanying horizons, foot or handhold, and even without its everchanging sky.”

- (An Angel at my Table, 1984).

In Nana’s time, people experiencing mental illness who were subject to compulsory treatment were consulted as an afterthought to treatment, if at all. From 1935-39, only 22.4% of patients were institutionalised voluntarily, and although the number of voluntary admissions had increased to 47.5% in the period from 1955–59, mental healthcare treatment was still very much in its infancy. As some indication of attitudes, the size of the institutionalized population formed around half of all in-patients in the country.

The thinking that guided best practice around those times was focused around medication and discipline, with therapy and support often parochial in their offerings. Writing in Health and History in 2003, Warwick Brunton described the model of institutionalised care until at least 1965 in NZ this way:

“The institution’s multiple functions of cure, care and custody took precedence over the significant values of patient dignity, individuality and privacy. Institutions imposed fundamental values like safety, order, neatness, cleanliness and occupation over lifestyle concerns…benevolent principles were espoused from the power relationships of paternalism and hierarchy that permeated a centralized bureaucracy.”

Like many people still do today, Nana had a complex relationship with hospital facilities. She remained deeply paranoid about medical professionals all her life. Nana often talked of doctors as being untrustworthy, and one time she retrospectively accused a doctor who had treated her once of putting her in the "Black Hole of Calcutta". It was something she alluded to one day years later, with no further explanation of her meaning.

But when overwhelmed, Nana would often choose the structure of institutionalised care, sometimes without advance warning. And so my mum’s memories of Nana as a parent are scattered with her disappearances:

“She’d drive to Porirua Hospital and book herself in,” she recalls. “and I didn’t know her behaviour was abnormal, because I had nothing to compare it to.”

Nana’s behaviour (that I can remember) might suggest a love for ramshackle disorder – hoarding old bric-a-brac, and tea cups piled high. In fact, she often felt most comfortable when surrounded by austere white hospital walls and crisp hospital corners. It was familiar to her. Although she had high anxiety about her health, she always liked being the focal point of attention, and for her, hospital facilities often elicited the kind of regular socialising she craved, while also absolving her of the responsibilities or routines of life she could find too much.

As Nana’s health became more fragile in her mid-fifties, and I was born, she came and lived with us. It was a time that also coincided with a running-down and closure of many psychiatric hospitals, in Dunedin and elsewhere – to ‘dip in and out’ of the system voluntarily as Nana occasionally chose to became harder, the expectations on families larger.

Her presence is a large, unshakeable part of my childhood memories – although where most of that time that typically invokes an idea of some adult figure leading you, reassuring you, or at least cajoling you, I’m left with recollections of the opposite, of having to be the wise emotional counsel for the first time in my life before I’d moved past picture books. Nana would often rely on mine and Hannah’s words to reassure her that there wasn’t some villain breaking into our house, or to soothe her distorted perceptions of family members and acquaintances.

Hannah also remembers an unabating anxiety, that would often manifest as fear for her safety: “I remember seeing her scared at night, being afraid and feeling deeply sad that at her age, with all her frailty, she could not have peace.”

There were other times when Nana sold our clothes for money, intent on gaining some financial freedom, uneasy with the restrictions imposed on her. I don’t remember quite when my parents realised that she had been doing this - only that as children, Mum would scold us about our clothes disappearing. Later on, in hushed tones, she bundled us up and apologised. She said that she had found out Nana had been taking and selling our clothes when she folded the washing, but we were given little explanation beyond that.

Other times she tried to grab smoker lollies off us, convinced we were hiding a nicotine habit from her (she promised not to tell Mum and Dad if we would give her a puff).

Even from when she was very young, Hannah understood that Nana was treated differently from other adults, even if she didn’t understand the reasons why that might have been. “I don’t remember the specific moment when I realised. Rather, I slowly developed an awareness of the boundaries that were placed on her and not other adults. She couldn’t go for a walk without supervision, her bag was regularly searched for the various items that she would taken from our household - and often, her voice would be marginalised or minimised to the size of mine.”

“It definitely wasn’t a mother-daughter relationship,” my mum muses. “I always feel like she was a creative creature who shouldn’t have had children, [that] she might have been happier.

It sounds startling from one of the kids in question, but by the time Nana came to live with us, her and Mum’s dynamic was already ingrained and had lost much of its original maternal bond, Mum was used to Nana being unpredictable, and so she often restricted what she could do - both as a safety mechanism, and as a coping mechanism.

Being exposed to the sometimes frightening extremes of mental illness can be hard for families. As well as the pressures of caring for someone who could, at times, simply detach from what we were experiencing as reality, there was also an enduring anxiety about whether the care given was right, and respectful.

“As a family we could try to comfort her as best we could, but none of us had any idea of the relentless and exhausting nature of her illness and ultimately, to us, her fears were of non-existent and non-rational things,” Hannah says . “I would get impatient with her and I remember I felt as though she could stop if she wanted to. I couldn’t understand how she could be so unaware of her mental illness, that demons had not always followed her,”

By the late 1990’s, my grandmother had lived through half a century of changing mental health policy in New Zealand, during which consideration for the health and social engagement of the individual had slowly become more of a priority. Many mainstream mental health facilities adopted an approach which focused on creating resilient support networks.

At the same time, it became something that educators thought it was worth sharing and shifting mindset on. By the early 2000s, at high school, it was emerging from the shadows – something DVDs and books told us we were expected to see respectfully, and that we were encouraged to accept in each other or ourselves.

Meanwhile, research in the field moved away from a confined view of mental health to a broader concept of wellbeing. By 2011, the Mental Health Foundation’s National Indicators report would treat wellbeing and mental illness as two dimensions of equal importance when considering care and the individual. Wellbeing extends to things like life satisfaction and personal happiness. This dynamic “recognises that people with a mental illness can still have high levels of wellbeing and, indeed, people free from mental illness can have low levels of wellbeing.”

Understanding moves fast in just a decade, and it’s easy to look back and wonder what could have been different. Although Nana’s mental health was considered very much present, I know her wellbeing was something my family endeavoured to provide for.

Yet Nana was treated differently. As Hannah remembers, her voice was not treated equally, nor were her opinions. In family conversations, nor was the way she recalled events.

At the same time, she simply couldn’t handle a lot of responsibilities I take for granted now. Faced with adult expectations, she’d get confused, and more often then not, frustrated. Instead of leaving her to muddle through, I know my family made efforts to make sure Nana felt secure, and that her essential needs met.

That makes it sound simple – in practice, a lot of what we did was. My father always picked up Nana’s friends and dropped them off for visits, and my parents organised social activities for Nana during the week so she wouldn’t get bored. As kids, we were expected to help her, and show her respect. My parents instilled the knowledge in us as children that our Nana deserved our respect and care.

There’s a paradox here that stings. I’m sure that Nana was frustrated by the restrictions placed around her, and at times, probably hurt by them, but it was also how she felt most safe. Our family role became, more than anything, caring for Nana in a way that made her feel secure, and loved. But I recognise that care for Nana today would have looked very different from her experience in the fifties and sixties, and even her later years living with us.

Though it sounds trite, the internet has changed the space for the better. The kind of resources that are now available online could have benefited Nana, my parents, and us as children – what’s more, the voices behind them aren’t just a fixed panel of experts. They’re people with lived experience of the mental health system with a platform to articulate what they want and why. Research is consistently providing more information, and public policy is trying to get the balance right between what facility care should look like and what community care should look like. More information would have made a lot of difference to all of us, but most of all to Nana.

Something that stuck in my mind at the time, and still does, is how little my grandmother was asked if she was okay, or how she felt about something. She was left to initiate a lot of expression herself, and so she emerged as a storyteller who often gained and held attention most when she spun elaborate tales and fantasies. In a busy, large family like the one I grew up in, it was easy to get lost in the chaos and strong personalities surrounding you. My parents did their best, but for Nana, and for us as children, the situation was not ideal, and was even harmful at times.

But these stories bound us all inextricably close to Nana growing up, and she knew we loved her fiercely. After years where she’d found herself absent and unavailable as a parent for reasons outside of her control, she enjoyed being surrounded and wanted by her grandchildren.*

The thing is, Nana’s positive legacy was profound. She had a keen sense of justice and compassion, which informed the interest she took in those around her. She would always initiate conversations with strangers, a habit my siblings and I carry through our lives and careers.

One occasion that springs to mind is when she was aged sixty-something and wandered off. Hours of searching ensued, only for us to find her three doors up, sitting on the porch with a bunch of students, talking and sharing a joint with them.

In reaching out the way she did, I realise the confusion and powerlessness Nana felt in her own life became a powerful and clear sense of empathy for others. She knew acutely what it felt like to feel out of place, and because of that, she had a warmth that transcended all kind of boundaries to those who felt misplaced too,

“She would approach some dangerous-looking situations - she didn’t care about their shell, she really connected,” Mum recalls. When she was growing up Mum remembers Nana taking in a small boy covered in scabs and dabbing his sores with disinfectant, and on another occasion looking after a 13-year-old girl who'd gotten pregnant.

And there’s a final memory, one that sets me down the path of where I am now and where I want to go. She granted me my first ever interview when I was 9 years old.

For an hour, I asked her about her childhood, and her opinions, recording her words on a clunky tape-deck. We chatted about her life as she had seen it - most if it fiction, all of it fabulous.

Nana gave me a fascination in learning the stories of people, regardless of how prickly they could be. She left me with an interest into the vulnerable heart that beats beneath the bravado some individuals present themselves with publicly - including many who, unlike Nana, will never be subjected to treatment, or even to a diagnosis, but will struggle in private. For those experiences, I am thankful.

I’ll always wonder what Nana’s life would have been like if she had been born into a time with more progressive view of mental health, and more modern views on the gender roles that compounded the expectations on her from when she was still a child. Would she have been an artist like Hannah, as Mum speculates? Or maybe motherhood was something she always craved - and she just required support that never came?

It hard to comprehend how different Nana’s life would have, or could have been. In my memories her character was always entwined, with her anxiety, her paranoia – all the other lows. But that was also the vibrant woman with stories to tell, and incredible compassion, and that was the Nana I knew and loved.

If you are seeking support or information about mental health visit -

http://www.mentalhealth.org.nz/get-help/faqs/