Forgers, Thieves and Conmen: A Brief History of Art Crime in New Zealand

Amanda Morrissey-Brown on art crime in NZ

Whenever I tell people that I’m pursuing a career in art crime, I watch with fascination as their faces contort through a series of emotions. Their eyes widen and their eyebrows disappear into their hairline, in an expression that is lodged somewhere between surprise, interest and confusion. I can see their brains frantically searching its hidden compartments for any sliver of information they might have on the subject. Not surprisingly, they usually come up with a handful of classic art crime stereotypes. I can almost see the images of these figures flashing across their eyes.

They think of Pierce Brosnan as the dashing millionaire Thomas Crown - the overly wealthy, yet strikingly cultured business man, who is eager to obtain objects money cannot buy for his own viewing pleasure. Or perhaps Harrison Ford as heartthrob Indiana Jones, the heroic historian who fights off tomb raiders in order to “save” ancient artefacts, proclaiming they belong in a museum. Audrey Hepburn may also make an appearance in the form of How to Steal a Million’s beautiful and cunning Nicole Bonnet, the devoted daughter who risks it all in order for the truth of her father’s art forging to remain undiscovered.

Since the early days of film, when it was black and white and silent (maybe with a little piano playing at stage left), art crime has been a hot topic. Films like The Three Scratch Clue (1914) and The Secretary of Frivolous Affairs (1915) told scandalous tales of theft, retribution, and resolution among the upper classes. It's in these early films that we can see the emergence of common conventions that are used when addressing the theme of art crime.

To begin with, a precious work of art must be stolen or under threat, and some noble person or group must therefore rescue the work or protect it. There is always the prospect of a romance either involving the innocent victim of the initial crime or a seductive femme fatale. In the end justice is done, and everything has a happy ending. These same conventions have grown to be repeated but also reversed (the villain sometimes becomes the antihero, and there’s generally some moral incentive behind the heist) in the Hollywood films we know and love today.

Subsequently, as an audience, we have a set of quick-fire reference points on the topic, reinforcing that art crime is romantic, exotic, scandalous, dangerous and comedic. These reference points sink into the back of the audience’s brains and rarely tapped into again (at least, not until the next Indiana Jones film comes out).

Crimes like the 2000 Stockholm Museum heist, where a team of armed burglars set two cars on fire to block roads and to distract police while they stole over $30 million worth of Renoir and Rembrandt paintings and made their get-away in a boat, commonly get described as being “like something out of a film”. Audiences are conditioned to a comfortable view that crimes against art are romantic adventures or comedic encounters, fraught with scandal and suspense.

But through its glamorising and romanticising, Hollywood succeeds in dropping the ‘crime’ in art crime all together and leaves it all seeming rather light-hearted and harmless. Even when we are faced with a film modelled on real life events like The Monuments Men, these historical accounts tend to get tainted by their Hollywood reproduction. Instead of these films being focused on the significance of these events, to allow us to fully grasp their complexity and implications of these events, they are reworked into a familiar, cosy story. These historical crimes against art become the back drop for the likes of George Clooney and Matt Damon to play out the same stock conventions of the ‘art crime film’ that we have seen time and time again: the threat to Art Itself, the dramatic chase and rescue, the budding romance, and justice served to the villain (who, as in Indiana Jones films, are cartoon Nazis).

My concern here is that a New Zealand audience’s understanding of art crime is being shaped to be inherently abstract. For most of us, art crime is a cosmopolitan phenomenon, disconnected from our safe, clean and green haven. It is an issue for people ‘over there’ or in the past. It unfolds in high profile museums and galleries in major cities around the world, or in the most exotic and obscure corners of the globe.

Of course, we’re not untouched by the phenomenon of art crime. A number of crimes against art, both high and low profile, have played out across New Zealand in the last 50 years, and virtually all of them allow us to cast a wider view than that which is presented to us by Hollywood, and to consider the social and cultural aspects of art crime; its motivations, its victims and its impacts.

*

In 1972, five late-18th century carved pataka panels, referred to as the Motunui Panels, were discovered in a swamp near Motunui in Taranaki by a local man later referred to in court proceedings as "Manukonga". It is thought that they were hidden there during a period of inter-tribal wars, in order to protect them from destruction or looting. Recognising the value these pieces would have in the European art market, the panels were brought from Manukonga for $6000 NZD by an English antique dealer named Lance Entwistle, and then quickly, silently and illegally smuggled out of New Zealand and taken to New York.

Entwistle sold the panels, with the help of falsified provenance documents, for $65.000 USD to the wealthy and controversial French collector, George Ortiz. This sale pulled New Zealand, and specifically the people of the Te Āti Awa tribe, into a rapidly growing international art crime economy. This economy was fuelled by members of the art word like Ortiz and Entwistle; Ortiz the final destination that fuels the demand while keeping clean hands, Entwistle the middle man who takes advantage of small-town locals and indigenous people who may not understand the true value of their cultural heritage, or who are desperate to make easy money.

Ortiz prided himself on his collection of Greek, African and tribal art - but he wasn’t some eccentric benefactor who’d fallen victim to an illegal sale. On the contrary, Ortiz was criticised, especially by the 1990s, for fuelling the illegal excavation and sale of artefacts and therefore enabling an abundance of international crimes against art to occur. In 1994, Lord Renfrew (Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge University) would later criticise Ortiz at the Royal Academy, stating that “our record of the past is being lost by illicit excavations and, of course, by illegal exports. Collectors are the real looters: they buy unprovenanced antiques and thereby finance the cycle of destruction.”

In October 1977 Ortiz’s daughter, Graziella, was kidnapped and a ransom of $2 million was demanded. Ortiz eventually paid the ransom and his daughter was returned as promised. Unfortunately for Ortiz, and to the joy of other collectors, the financial loss of paying the kidnappers ransom forced to Ortiz put 234 pieces from his collection up for auction at Sotheby’s, who valued the panels at £300,000.

It was through the details of the published auction catalogue that the existence of the Motunui panels was made known to the New Zealand government - who immediately issued a writ claiming ownership of the panels and demanding that no sale or disposal go ahead.

The panels were withdrawn from the ransom bonfire three days before auction, marking the beginning of a 40 year diplomatic and legal battle between the New Zealand government, England, and Ortiz himself, which reached the House of Lords in 1982. New Zealand had attempted to invoke its own Historic Articles Act of 1962, and the Customs Acts of 1913 and 1966. Our laws stated that it was unlawful for any person to remove an historic article from New Zealand (knowing it to be historic) without permission. The exportation of any historic article was a breach of this Act, and so the Panels would be forfeited to the Crown.

The issue with this argument, as was ruled by the Lords, was that this Act could only be applied to historic articles seized in New Zealand by New Zealand customs or police. Once the Panels in question had left New Zealand, and although they eventually ended up in the UK, the law could no longer be applied and New Zealand had no legal grounds to claim ownership (even though the Panels, from a lay perspective, appeared to have shifted from the dominion of Her Majesty to the dominion of Her Majesty – leaving aside the matter of the whānui it belonged to in the first place).

In short, if a smuggler was able to get a plundered historical article out of the country without being stopped by New Zealand customs or police, he was away and laughing. It sounds like the loophole to escape at the end of a caper movie. In reality, it was a free pass for the persons conducting the exportation and plunder, leaving those whose cultural heritage was being robbed with very few means of protection.

It wasn’t until after his death in 2013 that Ortiz’s family finally came forward and offered to sell the panels to the New Zealand government for a staggering $4.5 million. In the meantime, the matter had received international publicity, and allowed a number of world governments to receive a much needed wake-up call in regards to laws about protecting cultural heritage. Attorney-General of New Zealand v Ortiz contributed to the development of the Commonwealth Government Secretariat Scheme for the protection of cultural heritage, the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property and the UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects.

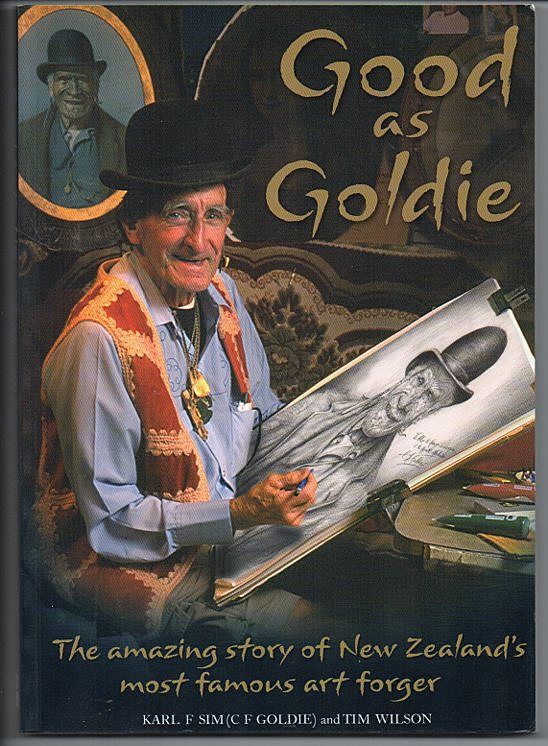

We can see from the Ortiz affair that New Zealand’s attitude to the protection of cultural and in particular Māori heritage, is generally taken extremely seriously. But not always: in the case of art forger Karl Sim, who forged paintings by some of New Zealand’s most famous artists, we’ve adopted a different attitude, and the villain became a fondly remembered antihero.

Carl Feodor Goldie (aka Karl Feodor Sim) was the first New Zealander ever to be convicted of art forgery. Sim was arrested in 1985, when it came to light that he had been forging and then selling as originals, paintings and drawings by artists such as Charles F, Goldie, Rita Angus and Colin McCahon in his Foxton antique and wine shop. Though it wasn’t lucrative – he spent his final years in an Orewa flat - he reportedly got a good kick out of fooling art experts who brought the works from his store. He was convicted on 40 counts of forgery, was fined $1000 and ordered to complete 200 hours community service, which included painting the Foxton Town Hall and the public toilets. It wasn’t until after his court case that Sim legally changed his name to Carl Feodor Goldie, finally able to truthfully sign his own works as C.F. Goldie.

This case is a clear example of the light-hearted attitude New Zealand tends to associate with some crimes against art - yet it reveals a case that does not fit neatly into the Hollywood construction of how a crime against art should be played out.

When reminiscing about her brother after his death in 2013 to the Manawatu Standard, and referring to him by his preferred name ‘Goldie’, Margaret Jones said Goldie had a “communist way of thinking", though his kind, gentle demeanour earned him respect within his community. She recalled that “the magistrate that sentenced him came up from Wellington to Foxton during his trial and went into the four pubs in the town. He couldn't find anyone that had a bad word to say about him [Goldie], and I think that was part of the reason he got off it so light.”

Speaking to the Herald, Jones explained that “he didn't do it for money or anything, he did it to beat the establishment - because arty people can get a bit snooty. But beating them was his main aim." Goldie took a private pleasure in duping people who held themselves in too-high-a regard in the art world – rather than muscle in and take his cut of the glitz and glory, he played against type by expertly deflating its values. When he took part in an irreverent exhibition called Fakes and Forgeries in his small hometown at the age of 83, parochial gallery owners wrote to local government and Creative NZ blustering about how a convicted criminal was being rewarded with any attention at all. It felt fitting.

*

The case of Anthony Ricardo Sannd falls even shorter of the Hollywood-induced expectation of crimes against art. On the fact of it, Sannd’s theft appears dramatic and well-planned, but he was neither a villain, nor an altruistic antihero, nor an eccentric. Sannd just fell in with the wrong crowd early on and began a spiralling decent into a life of smaller crimes. He claims he developed PTSD from a stint as a war photographer, received ECT at Oakley Hospital, then ended up carrying out an extraordinary, doomed art heist.

On a Sunday morning in 1998, Sannd stormed into the Auckland Art Gallery, brandishing a P220Sig-Sauer pistol in one hand and a Winchester Defender single-barrel shotgun in the other. Sannd shoulder charged his way through an unsuspecting security guard and ripped the French painter James Tissot’s 1873 masterpiece "Still on Top" right off the wall.

There was no hesitation as he bee-lined straight for the Tissot. Snatching it off the wall, he smashed the glass and pried the frame off with a crowbar. He wrenched out the canvas, roughly rolled it up and stuffed it into an ex-military carry bag that he slung over his shoulder. Running back out the way he came to his waiting motorbike, Sannd fired a warning shot into the air to discourage any would-be heroes, then sped away.

After eight days, one ransom note that was mailed to an Auckland lawyer demanding $500,000 for the painting, and a claim by Sannd that he had been commissioned by a Hong Kong business man to steal the painting for him, police found the badly damaged Tissot hidden beneath Sannd’s bed. He was sentenced to nearly 17 years for the theft and two other robberies – by NZ standards, an extraordinarily long time, and on par with some of the most violent offenders. In early 2012, he was out and offering a rueful tell-all to the Herald on Sunday’s Jonathan Milne about rebuilding his life. Less than two months later, he was back in jail for stealing a motorbike and breaching parole, now 64 years old.

Just as every other country must deal with variations of art crime, New Zealand art crimes are heavily influenced by the local environments out of which they emerge. They highlight the processes of colonisation, or the paradoxical celebration and censure of Kiwi egalitarian impulses, or one man’s desperate isolation.

Each of these is a tall tale, and each has attracted international notice over the years. What happened to Auckland artist Dean Buchanan between 2004 and 2007, though, brings home the understanding that art crime can occur on a much more frequent, local and troubling scale.*

In 2004, Buchanan began a casual business relationship with a man named Ian Malcolm Baikie, The arrangement was simple: Buchanan would give his paintings to Baikie, who would then sell them up and down the country on the artist’s behalf for a commission.

This agreement lasted only a short while before Baikie began stockpiling a couple of dozen’s worth of Buchanan’s paintings without his knowledge. For years afterward, Baikie quietly continued to tour New Zealand, selling paintings in Wanaka, Napier, Karamea and Piha - not on behalf of Buchanan, but as Buchanan himself. When the real Dean Buchanan eventually got wind of Baikie’s scam, he confronted him and demanded Baikie either give the paintings back or pay the money received from his sales.

When Baikie refused, Buchanan went to the police. If it sounds harebrained, it was: Baikie wasn’t a debonair, Catch Me If You Can-style impersonator but a craven opportunist. Simply stealing Buchanan’s paintings was one thing - by impersonating the artist himself, Baikie significantly impacted Buchannan’s professional and personal life. Speaking to the Sunday Star-Times in 2013, he was still forbidden from naming his impersonator ahead of court – but he could confirm that “Dean Buchanan” had snubbed old friends, sexually harassed women at markets, and burned the artists’ bridges with gallery owners.

The case went to trial in 2014, and Baikie was eventually sentenced to 150 hours community service and ordered to pay $5000 as an emotional harm payment.

Nationally, Buchanan is one of New Zealand’s better-known contemporary artists – at first blush, the idea of causing a prominent figure that kind of damage with an inept con seems hard to believe. But when you look at artists who are more well-known in local communities, or particular regions of New Zealand, the reporting on crimes against art that effect these artists is thin on the ground.

Obviously, not everything makes it into headlines But that lack of reporting creates a further lack of understanding that art crime is something that can affect any artist or their family, any dealer gallery and any collector. As a member of the New Zealand art world you may not get your stories told, but you can still get screwed over all the same.*

Souzie Speerstra is a talented, self-taught, and well-regarded Hahei-based artist whose experiences reflect the real nature of art crime – experiences which seem mundane (that even seem like simple commercial disputes from the outside) but that can be almost career-ending.

Beginning her artistic career as a photolithographer, Speerstra began painting in 1990. Her preferred medium is acrylic on canvas, and she commonly deals with regional subject matter; landscapes, seascapes, seaside getaways. Her online bio states that she “has an island mentality and loves Kiwiana–the boat, the bach - the experience and thrill of being brought up here with the freedom and activities of a Kiwi youth.” Her work is exhibited throughout Auckland and the Coromandel Peninsula.

At the beginning of her career in the early nineties, Speerstra had her first exhibition in a commercial Queen Street gallery in Auckland. The day after the exhibition ended, she returned to collect her pieces, only to discover that the gallery owner had emptied the space overnight and disappeared with her work.

Speerstra was devastated. This betrayal was a huge hit to her self-esteem - recalling it to me 25 years later, she describes being left feeling like she was nothing. As a single mother trying to raise a 2-year-old son, she was faced with a mortgage, bills to pay and declining EFTPOS cards. This event rocked both her professional and personal life and left her with few means of income.

Surprisingly, Speerstra soon discovered that the gallery owner had returned all the works of well-known figures like Louise Henderson from the exhibition, but vanished with all the works by unestablished artists. “I saw no money from my sales, but did manage to track him down and get my unsold work back.” In doing so, Speerstra sought the help of fellow artists and the non-profit group Artists Alliance, then newly established. There was only so much that could be done, and it was hardly a police priority - in the end, it was down to Speerstra to get her works back herself.

Speerstra’s investigations eventually discovered that the gallery owner’s assets, including his house, were all in his mother’s name, “He had so much beautiful artwork... and got to keep it all. A few years later, I heard he'd opened a new gallery.”

The experience left Speerstra acutely aware of the lack of protection and rights in place for artists. This dose of reality only made her more determined, and reminded her of the importance of artists sticking together and looking out for each other. “In the end, you have to suck it up and move on or it will destroy you. It’s soul-destroying. But you learn from it, you learn to trust your galleries.”

Just as Speerstra recovered from her first brush with art crime, she was hit by another. This time, it was on an international scale. In 1990, she was asked to provide half a dozen works that would be exhibited alongside other examples of Pacific art in the opening of a new terminal at Singapore’s Changi Airport.

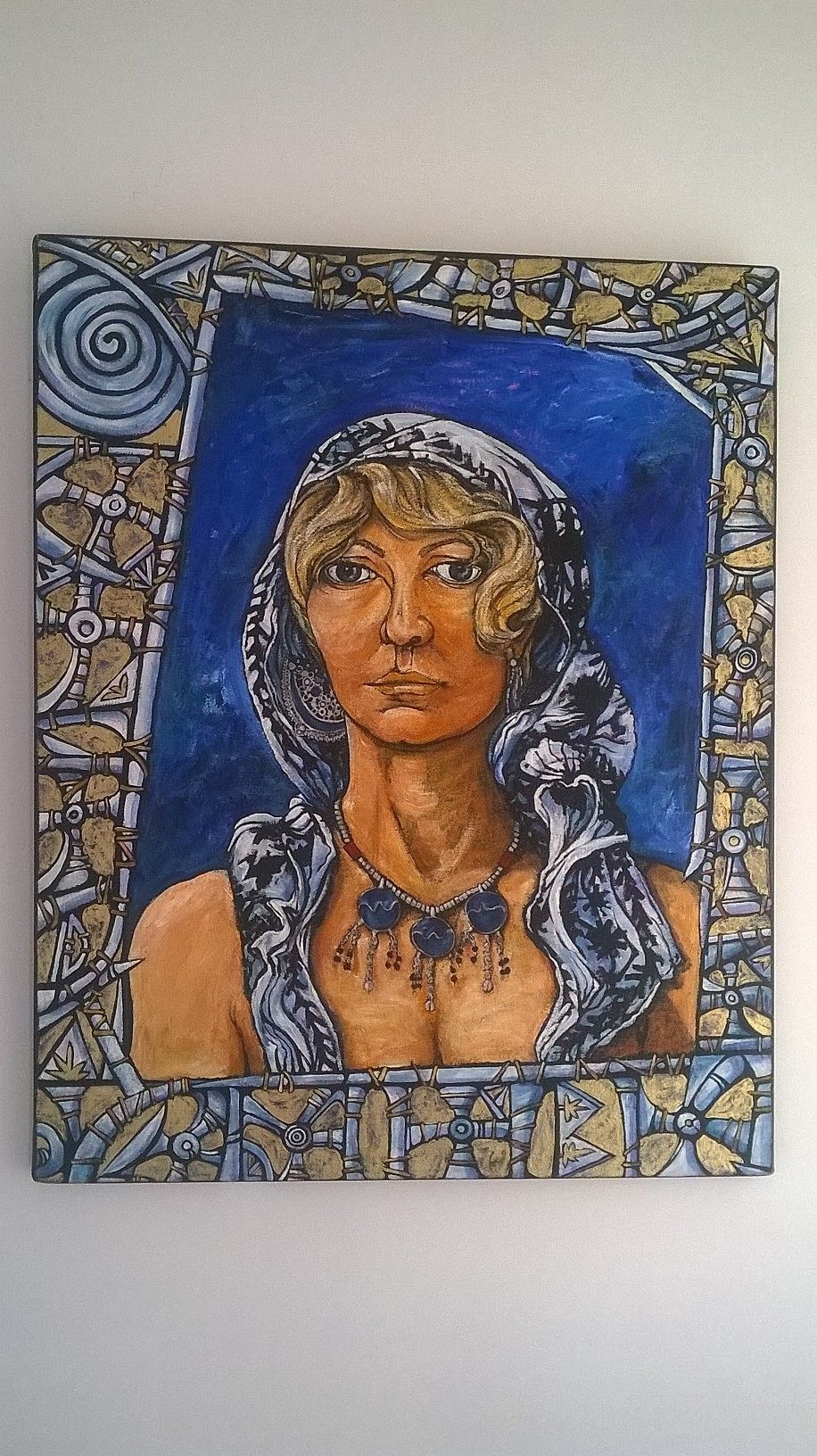

Speerstra’s gallery at the time paid her for the use of her works, but lost track of them once they were shipped overseas. There was one work in particular, a self-portrait of Speerstra, which she had not wanted to be sent away. In a miscommunication, it was packed up with the others and sent to the exhibition. The self-portrait ended up being used by the exhibition organisers to promote the Year of the Woman - it was reproduced on the cover of a diary that was provided as a gift to first-class passengers coming through the new airport, and as a backdrop in photo booths where diplomats could have their photos taken while the exhibition was running.

Speerstra’s other works were displayed with price tags that were over four times the amount she had been originally paid. “I had a few phone calls at night from overseas asking how much my paintings cost. If I remember correctly, they had marked them up by 700%.” The gallery representing Speerstra was never paid for the works that were ‘sold’ at the exhibition, nor was it ever consulted about, or paid for, the use and reproduction of Speerstra’s self portrait to promote the ‘Year Of The Woman’.

About a year later, Speerstra’s gallery sent a representative over to Singapore to talk to the people who had run the exhibition. Sitting in the office of a solicitor, the representative silently beheld the vibrant self-portrait of Speerstra hanging on the wall behind the Singaporean’s desk. Shockingly, the solicitor attempted to claim that all 5 of Speerstra’s paintings had been stolen and that there was little the exhibition organisers could do. With that, “the guy reached over the desk, removed my portrait from the wall and walked out... It now hangs in my hall.” Unfortunately, Speerstra’s other works were never found.

The most distressing incident suffered by Speerstra is the most common, the one least likely to be seen as a crime, and the one that reveals the most systemic disregard for an artist’s livelihood. At one stage, early on, she waited 8 months to be paid for an exhibition. It’s not the only time she was left hanging, but it was the worst. This is a clear demonstration of the vulnerability of artists and the power imbalance between those who create art and some of those who deal and exhibit it. “I was paid after ringing his wife and begging,” Speerstra tells me. “I had just had the power officially cut off on my house.”

Experiences like Speerstra’s make those comedic and light-hearted tales of art crime disintegrate. The proportion of work that ends up hung in international galleries is but a tiny percentage of all art, and the publicity of art crime is similar. Art crime isn’t something that happens – a theft, a forgery – once the work gets famous enough. Instead, it’s local artists trying to make a living off of their talents and passions and instead getting a face full of mud, either because they lack the means or the sufficient legal training to protect themselves.

So the puffed-up representations that come to people’s minds first – your Crowns, your Joneses - are a hindrance, rather than informative in the field of art crime. They mask an abundance of everyday incidents that don’t get a first glance, let alone a second. But if we do stop for that glance, it’s clear - there is a need here for more to be done to protect artists, both their works and their livelihoods.