Gender and Other Performances

Bianca Michelle writes about the uphill battle of making theatre while trans in New Zealand - and about the trans artists carving out new paths.

Bianca Michelle writes about the uphill battle of making theatre while trans in New Zealand - and about the trans artists carving out new paths.

It was at drama school I got the first unavoidable signs that I wasn’t cis.

There had been plenty of big flashing neon signs prior to this. But for me they were illegible, just bewildering figments I learned to ignore. The only Trans person I was even aware of growing up was Coronation Street’s Hayley Cropper, played by cis actor Julie Hesmondhalgh and grumbled about by family members who didn’t appreciate such things being brought up on dear old Coro. But acting gave me an outlet for my discomfort with myself. I could pretend to be someone else for a while, and it became my safe space for exploring my issues with my identity.

This all changed when I entered training. Tutors told me that I wasn’t embodying masculinity in the way they desired, something that completely bewildered me. I looked like a man, didn’t I? I had stubble and wore trousers, and until this point I thought that was more or less it. I didn’t know how to perform masculinity. I hadn’t ever imagined I’d need to. Its absence was something I couldn’t explain or understand.

I was told that it was important for me to find that missing masculine essence if I was to have a career in the arts. I wouldn’t stand a chance in a competitive marketplace unless I could represent the kind of standard-issue manliness that would be required for most of the parts I would be considered for. I was offered solutions like working out (manly!), punching things (so manly!) and, in one exercise, going out into the bush and gathering wood (can you smell the testosterone yet?). Shockingly, this didn’t fix anything. I was consistently told I wasn’t doing something, I could just never figure out what.

I don’t blame my tutors for not understanding, or finding actual solutions for, my identity issues. But these surface-level fixes only deepened my frustration and confusion. By the end of my time at drama school, I felt at a weird distance from myself. Any attempt to bridge the gap only made matters worse; it caused me to lose my grip on the fragile facsimile of masculinity I had been constructing. Theatre had been my sanctuary. Now it was a space of discomfort, a space where some fatal flaw in me had become horribly visible. It was two more years of fumbling with the broken bits of myself before I finally admitted what was really going on.

But after I’d wrapped my head around my gender identity, I was still left wondering if there would be any kind of place for me in theatre. Even those who fit the desired mould far better than me, whose presentation was ‘marketable’ in this cis-normative industry, were encouraged to lose weight, gain weight, get a haircut, get braces, fix whatever was deemed not quite right. I couldn’t see someone like me making it in this kind of environment. The only time I saw a Trans character on stage during this period was in Silo’s 2013 production of Mitch Tawhi Thomas’s Hui. She was played by cis actor Stephen Butterworth; in the post-show Q&A he exclusively referred to her using the t-slur. (Silo’s website still misgenders her to this day.) Otherwise, there was nothing.

I was told that it was important for me to find that missing masculine essence if I was to have a career in the arts... I was offered solutions like working out (manly!), punching things (so manly!) and, in one exercise, going out into the bush and gathering wood (can you smell the testosterone yet?).

I have seen many, many plays, companies and thinkpieces that promise to interrogate the way we think about gender on stage, but often avoid mentioning Trans people at all. Avenues for queer representation under-represent us: the long-running anthology show Legacy Project, for example, hasn’t featured any stories by or about Trans people in two years, having previously managed about one to two short plays out of six each season. I’ve heard left-leaning middle-class kids boast about how inclusive the broader theatre community is without understanding the advantages they’ve had, how many boxes they’d checked off before they’d even started. They’re the ones who have met the requirements and are able to thrive within the industry’s narrow parameters; they’re the ones most likely to be considered for roles in productions on mainstages – on any stages. Everything seems inclusive when you’re already safe on the inside.

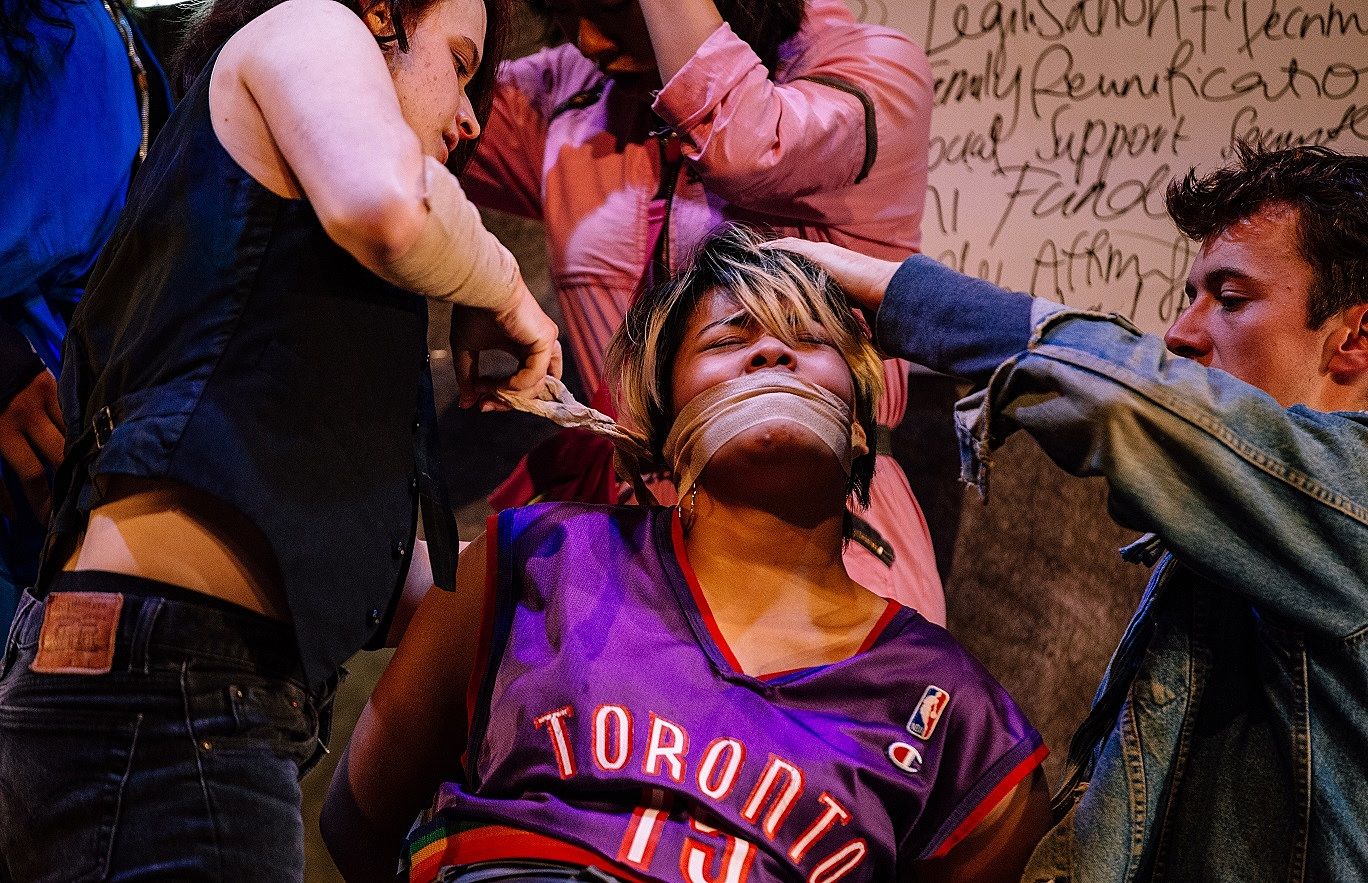

Yet, in March and April this year, two pieces driven by and featuring Trans artists were staged at the Basement, COVEN’s Ethera and Jaycee Taunvasa’s curated narrative series Woven Womxn (a third, the Breaking Boundaries-produced My Kuia, centred Takatāpui and gender-diverse performers). On-the-rise arts collective FAFSWAG was the company in residence at the Basement in 2017 and is taking over the mainstage in September as the second show in Basement’s Visions programme. Queer cis writer Joni Nelson’s black comedy 8 Reasonable Demands played in Auckland Theatre Company's Here and Now Festival: even a main stage was giving space to a story in part about Auckland's trans community. When I first heard about some of this I was a bit taken aback. You have to understand that, for marginalised people, this kind of tangible evidence of progress can be a bit like finding an oasis while hopelessly lost in middle of the desert. I was surprised, on this occasion, to not wind up with a mouthful of sand.

Other Trans artists have had similar experiences to my own. Jadwiga Green is one of the writers behind Summer Camps, a performed oral history about the lesbian summer camps of the 1970s and 80s that recently featured in the New Zealand Fringe Festival. Jadwiga earned a nomination for Most Promising Emerging Artist at that year’s New Zealand Fringe Awards for her work on the production. At university she was pushed to “go for really hyper-masculine roles,” she tells me, “things like Stanley from A Streetcar Named Desire.”

“The moment I came out,” she says, “especially being a super-unique six-foot-seven, powerfully built Transgender woman, all of a sudden roles just dropped away.”

Jadwiga found the dearth of material for Trans women so disheartening that she nearly left theatremaking altogether. “I didn’t think they would let me go from ‘you should play Stanley’ to ‘you should play Blanche,’ that wasn’t going to happen, and that was really disheartening. So I gave up acting and didn’t act for about two or three years.”

“The moment I came out, especially being a super-unique six-foot-seven, powerfully built Transgender woman, all of a sudden roles just dropped away.”

Jadwiga’s account feels familiar to me. After I began to develop a clearer sense of who I was, I became unhappy with playing male roles. I wanted to get as far as I could from the mask I’d had to create during training. I was worried that transitioning would basically cut my prospects to nothing, but I no longer wanted to force myself into a masculinity when I knew pursuing it would only make things harder.

Jadwiga emphasises that she has been fortunate and things are going well for her. She has a producing partner who has helped her get her work to the stage and her next show, comedy solo You Are the Book of Revelation, opens at BATS later this month. But she points out that this is not a position all Trans people are in. “The only other option to getting my work made is doing everything myself, which I think is a burden a lot of Transgender people come up against. They...have to sort those roles themselves, upskill themselves and take on extra burdens to do what they want to do.”

Trans people are new and unfamiliar enough to some in the theatre industry that it can be difficult for Trans makers to attract interest in their projects. While there are plenty of people who support and affirm work by our community, Jadwiga says, projects centring on Trans people and issues affecting our community are seen as “difficult to touch.” Even her producer was concerned about whether he was the right person, as a cis man, to be taking on a project centred on Trans issues.

This well-meaning hesitation makes it difficult to attract producers and other practitioners, which in turn makes it necessary for Trans artists to try and wear every hat in the work they make – but this isn’t something everyone will be able to do. Not only is this a significant obstacle for Trans artists, it also means that when established companies decide to take on Trans issues the result is work like Silo’s Hir or Court’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch: shows driven by cis practitioners, largely targeted at cis audiences, and, in the case of Hedwig, with another cis actor in a gender-diverse role. In a 2017 interview with The Pantograph Punch, FAFSWAG’s Tanu Gago said that advertising agencies attached to festival projects would come in and try to “translate our brand into something palatable and consumable for Susan and her husband and her nuclear family on the North Shore.” That’s a problem for our community, which has already long had its voices appropriated and sanitised.

Pacific Institute of Performing Arts graduate Daedae Tekoronga-Waka, who recently starred in 8 Reasonable Demands, takes an upbeat view of the prospects for Trans artists in the near future. She describes the recently defunct PIPA, a performing arts school based in Avondale that was forced to close in 2017 following funding cuts, as “a space where Takatāpui and Akava'ine could thrive because they were all on board for you being who you were and expressing your authentic self.”

LGBTQ stories are an emerging niche market, she says, and the market is growing steadily. She’s enthusiastic about the now, about how this is an excellent time to be working as a Trans artist. “From my experience,” she says, “I’ve never had much of a problem of trying to find where we fit in the industry. I’ve seen the space where we fit, I see the high demand for it. People are beginning to open up that space for us.”

"I’ve seen the space where we fit, I see the high demand for it. People are beginning to open up that space for us."

That doesn’t mean Daedae isn’t realistic about position we’re in now, though. Trans artists are required to be versatile and take many different roles, she says, even ones that don’t match their own gender identity. She notes a few occasions when she has been able to play gender-diverse characters and has taken part in creating roles for herself, such as in last year’s development season of Tampocalypse for the recently established Embers Collective at Auckland’s Te Pou Theatre. Still, though, Daedae emphasises a need for pragmatism when these opportunities aren’t available.

Daedae’s dream, once representation has increased to the point where she has a “shit-ton of competition,” is to create “a pool,” a vast community of multi-disciplinary Akava'ine and Takatāpui actors, dancers, artists: “You know, of many forms.” She hopes to be able to bring together LGBQT practitioners from many different disciplines, so every aspect of production in any given project can be imbued with authenticity on all levels. “I don’t want one cis person in there. Because it just won’t pay homage.”

Perhaps the difference in our viewpoints is a sign of generational change. Daedae had been toying with the idea of entering the performing arts industry six years earlier, but “something in me was like, ‘not yet, hold back and wait.’” “I knew there was a niche market coming,” she says, a place in the theatre community and industry where she could tell the stories she wanted with artists who would truly understand what was being told.

I graduated five years ago. Maybe if I’d waited I’d have found a much more accepting and understanding industry. This, of course, is a persistent problem for marginalised people – if you wait long enough of course things will get better. It's the right now that’s the problem. In addition to the hard work required to break into the industry at all, Trans artists also have to make the additional effort to push that ‘niche’ open wider. The fact that Basement Theatre seems committed to providing space for Trans practitioners is wonderful and provides a strong example for other companies and spaces; and companies like FAFSWAG and Breaking Boundaries, who are working with established spaces and trying to blow up cis theatre frameworks, are genuinely exciting. But a niche is still just a niche, carved out within a framework that is tied to existing cis-normative practices. Spaces within a niche are hard won and easily lost: just look at PIPA. Without them, we’re too often left out in the cold.

Still, it makes me think that maybe I’ve stayed away for too long now. We’re a long way past Hayley Cropper, after all. There’s undeniably more now, more new opportunities appearing. My relationship with my former safe space is different now: it’s no longer the only outlet I have to explore my identity, and as a result I don’t need it in quite the same way I once did. But if there’s the possibility to participate as the person I actually am, rather than the one I tried to construct at drama school, it could once again be my space. A space where I can know myself better.

Header image: Woven Womxn at Basement Theatre. Image credit: Pati Solomona Tyrell.