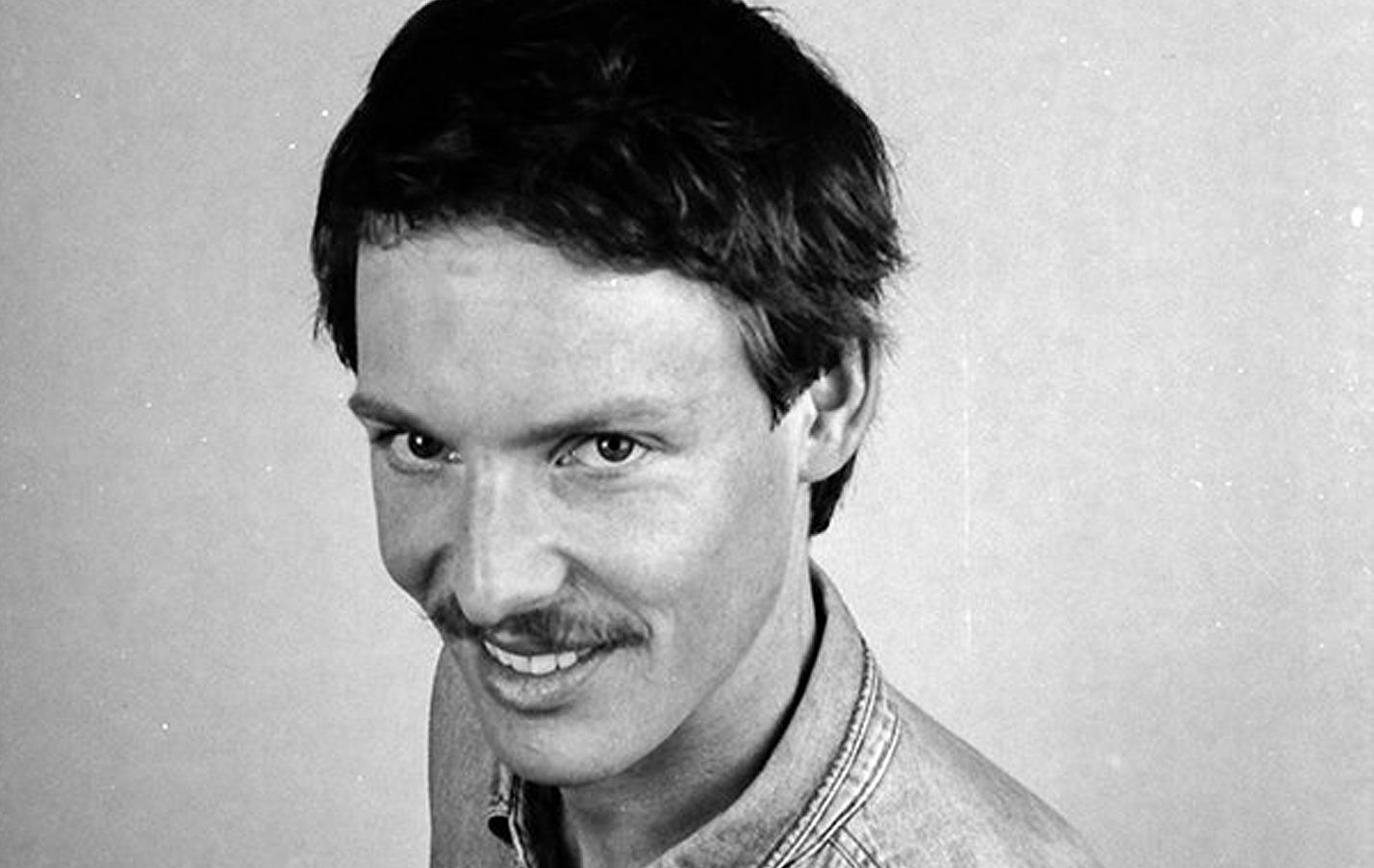

Guy Montgomery on The Most Fun Thing He Can Do

We chat to this year's Billy T Award winner, Guy Montgomery about stand-up, vulnerability, and why he does what he does.

“I couldn’t wrap my head around it,” says Guy Montgomery, though he isn’t talking about winning this year's Billy T, the most prestigious award for comedy in the country. He’s talking about the competition itself, as a concept: It messed with his game. Made him feel like he was no longer doing stand-up for himself.

“Everything turned into a discussion about the competitive element, which was something I wanted to avoid – I couldn’t measure what I was doing against what those guys were doing. They’re completely different people.” It took a six-hour conversation with a friend's flatmate, an American who was raised a Mormon, to quell his anxiety. The three spent an afternoon dissecting the process of how you reason yourself out of an irrational framework. “In talking it through, I had these moments of epiphany where saying out loud the thought I already knew – I’m not in competition. I’m just making a show I want to make because that’s what I want to do - realising the truth in that thought was a massive wave of relief.” He describes it as one of the best conversations he’s had in his life.

On the topic of winning, he simply says: “I felt weird.” He attributes this to the fact that he struggles with compliments. “I can give myself a very honest and fair assessment of how I’ve gone with a certain thing, but if what I feel – which is very specific and occasionally very neurotic – doesn’t jive with the feedback someone has given me, I struggle – if it’s really lovely feedback – to take that on board.”

Guy Montgomery: inoffensive, charming, and deeply self-aware; speaking easily and with a strange formality that makes you feel like he's putting on a character; and thinking far more than you might expect – given how relaxed and silly his comedic persona is, given how hard he works to make it appear natural – about his craft.

I tell him he seemed nervous at Last Laughs, where he and the other nominees performed a short set. “I was,” he says immediately. “I didn’t relax into it. I think anyone who hadn’t seen the show wouldn’t have known, but my brain definitely wasn’t open. I was rigid.”

He gives a rundown of his Comedy Festival season, too, analysing it in brief bursts like a sports commentator. “Last week in Auckland.” He titles it. “Tuesday I felt amazing afterwards. I was very happy. Wednesday: my friend Ryan filmed it for me, and I felt not very satisfied with my performance. Thursday: very happy. Friday: the best show I’ve ever done in my life, and then Saturday: running on fumes, slightly drunk fumes, but gave it everything and was pleased.” He leans back, seeming satisfied. “What night did you come?”

I tell him Wednesday. He nods. “I got a bit blue for about half an hour after that show.”

I ask him if there are factors in his control that affect his performance. “I don’t know,” he says, shaking his head. “I don’t know.” He does this often: feigns a level of indifference towards an idea before revealing he’s actually thought about it a lot. It’s not indifference he’s expressing but indecision from overanalysis.

“It was weird,” he begins again. “In Wellington I had this one night.” He begins listing all the factors that led to it being a weird experience: “I don’t eat before I perform. I’ve never done an hour before. This is the first time I’ve done an hour.” So he doesn’t eat. “It’s a combination of nerves and it became superstition.” Before he performed, he ate three small tacos. “Very small,” he clarifies, “not enough to fill you. But it threw me off, and then there was this knot of tension inside and I could feel it right up until the intro played and I had to go onstage and it was just there, for the first 20 minutes.”

“Even when the first laugh came,” he says, “there wasn’t the relief I was looking for.” He felt off. “And other than the tacos, there was nothing different, so I don’t know. I think with experience it gets better.” He shrugs. “Or worse. I don’t know anything.”

On paper, Guy appears far more neurotic than he seems in real-life: what’s lost in translation is the way he delivers everything in a goofy yet straight-faced, unconcerned fashion. He never lampoons anybody except for himself, and his show this year, Guy Montgomery presents a Succinct and Concise Summary of How He Feels About Certain Things, was marked by this too, trading in absurd sketches and self-deprecating gags.

It’s taken him a while to find his comedic voice. “At first I was just ripping off everyone I liked. I was doing an impression of a stand-up comedian.” He cites Peter Cook and Dudley Moore as key influences. “I’ve got a book of all their stuff, and whenever I had the willpower and discipline, I’d try to write a sketch to that exact formula.” It’s a well-worn truism that explaining is losing when it comes to telling a joke, so making comedy your business and then analysing the mechanics of what works is the sort of agonising, forensic process that a good show conceals.

He also notes that when he first started, he wasn’t as invested in the jokes he was telling. “I was just latching onto anything that made people laugh and performing it as best I could as me, but still pandering, in a sense.”

It’s one of the most striking characteristics of stand-up: the degree to which a comedian makes themselves vulnerable, more than any other artform, to an audience who’s arriving with a preconceived notion of the desired outcome of a show. It’s also a transmutable form: always alive, always responding to its audience. It takes an impressively stoic confidence in yourself to not let it get to you.

“It’s an ongoing compromise,” Guy agrees, “between communicating what you want to communicate and winning the audience over.” He found being nominated for a Billy T a strange experience, too. “It was difficult trying to keep the show true to the comedy show I wanted to make, knowing it was going to be judged.”

He credits improv with helping him relax into his own style. “You’re forced to become comfortable in silence. You’re forced to find something in nothing.” He spent four months last year doing this at every gig he did. “I’d just go up there and make it all up on the spot… Naturally you’re gonna tank a few times, but if you get into the zone, some of what comes out of your mouth is stuff you want to be saying.”

That comfort is tangible in his set. You can tell when somebody’s performing a rote-learned show; there’s a rigidity that fails to allow for natural response, like some old American sitcom with a stock laugh track. He tells me about 80% of his show was prepared material, and the rest was improvised each night. “Once you get to know the jokes well enough,” he says, “you always know where you’re going to get that nice crescendo laugh, so you can dip after that and just mess around.” He pauses. “It’s a really weird version of light and shade.”

*

Guy may have only made his full-length debut this year, but he committed to comedy a long time before that. He started doing stand-up shortly after he moved to Auckland in 2010, but became dissatisfied with his work ethic. He was too easily distracted, having too much fun, and knowing this, he knew he had to leave.

He went to Montreal, where he worked in a sushi restaurant and did stand-up 2 or 3 nights a week. “Still no direction,” he narrates. “Really aimless. Just having a cool time.” It wasn’t until he moved to Toronto a few months later that he hit his stride. “Every night I got to perform,” he recalls with marvel. He hit all the open-mics he could find and hustled. “I set myself a minimum of ten gigs a week,” he states. “Anything over was gravy. Anything under wasn’t good enough.” There’s no arrogance in the way he outlines this: he’s frank about his flaws, too. “It was the only way, because I didn’t have a good enough writing ethic. It was the only way I was going to fast-track my progress as a stand-up.”

He’d resolved, when he left New Zealand, that he wasn’t going to return until he’d “made it or completely capitulated.” But after he’d been in Toronto for seven months, his friend Tim Lambourne approached him about co-hosting a new late-night show TVNZU were planning on launching. He said no at first, but then he realised he was being silly. “How many times in your life do you get asked to do – no matter how small – a late-night show? So I was like: okay, fuck. I applied for it.”

He plans now to head to Europe, and then New York. “I want to keep doing fun stuff,” he says. “Stuff I think is funny.” He can’t stay in New Zealand, because he can’t do stand-up every night in New Zealand. He wants to grow, and he can’t do it here.

I ask him the question that crosses my mind whenever I see a stand-up gig: How does somebody get into comedy? “I did it in the first place because I thought I’d be good at it, and I didn’t really want to do anything else. I looked at everything objectively and asked: what do I like doing the best and what am I the best at doing? And the answer to both of those questions was: being funny.”

And now: “It’s just really fun. It’s really fun to make people laugh.” He considers this briefly. “It’s one of the most fun things you can do.”