Haunted fibre: exorcising technology through horror

Eleanor Woodhouse digs into the uncanny connection between technology and the horror film genre, and what it says about us.

I started to notice it at this year’s film festival: a pervading spookiness that infiltrated an unusual number of the screenings. Usually just one ghost per ‘serious’ film is strange enough, but whether they were CGI, directly referred to, implied or metaphorically present in the form of now-deceased filmmakers, ghosts popped up time and time again. Every time they did, so were phone and laptop screens. It seemed that everyone was haunted, and everyone was skyping.

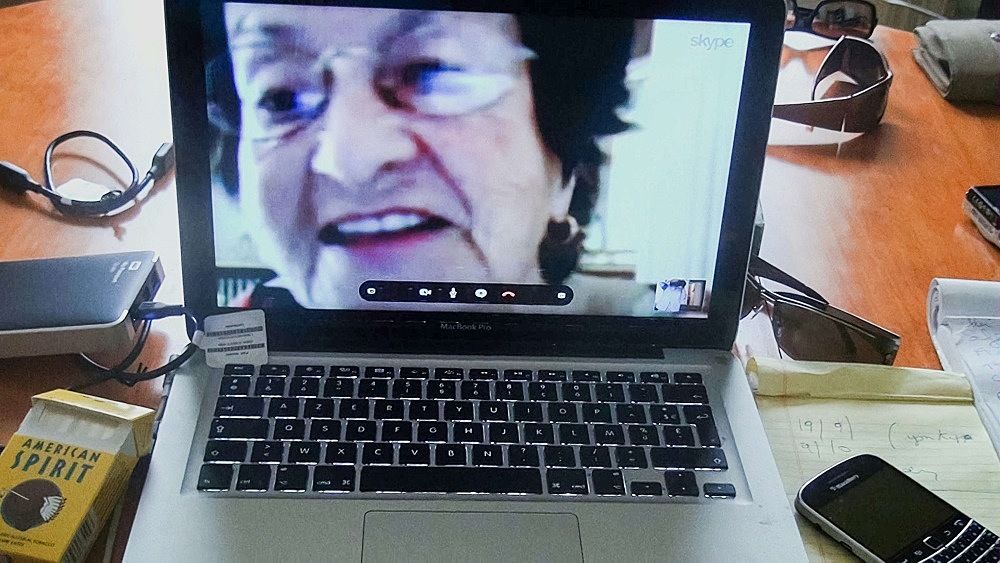

It began with No Home Movie. The haunted in this case was the audience, who were well aware that neither of the documentary’s subjects – director Chantal Akerman and her mother – is alive today. Already unnerving, their distance became even more pronounced as we saw their images flickering on computer screens in video calls. The image of Akerman and her mother as blurry faces in the monitor lingered with me, and resurfaced more strongly while watching Oliver Assayas’ Personal Shopper.

I went into the film already knowing it would be a horror, but there they were again – skype calls (better quality this time) and incessant texts. Then in Alexander Sukarov’s Fancofonia, the captain of a seemingly doomed cargo ship skypes our narrator from a savage storm, before the data-moshing obliterates the screen, and it cuts to the Louvre, 1940. By the time I went into Werner Herzog’s documentary on the Internet, Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World, I was ready to extract all the mystical implications I could from it, and there were plenty. Finally, I remembered Zhang Hanyi’s Life after Life, seen earlier in the festival, which while not dealing with the digital, still linked ghosts and technological progression in inextricable ways. Five is quite a crowd, too many for coincidence, and I realised that much of the media I’d consumed in recent years that engaged with ghostliness – be it music or art or film – spoke from a digital perspective. If not coincidence, then a mystery: why is it that in the 2010s ghost stories are told by respectable creators, and using the language, logic and context of technology?

The first place to look for answers is the most obvious: horror, and the new direction it’s taking as a genre. There is the claim that horror’s become legitimized, which has been a long time coming considering Pan’s Labyrinth was made ten years ago. Opposing this is a second contention that, rather than gaining respectability, horror is actually disintegrating or dispersing into other genres. We see this in Personal Shopper, which assimilates the genre’s conventions into the far more respectable festival-circuit drama. Kristen Stewart’s Maureen – the beleaguered personal assistant the title refers to – holds as much psychological depth and is as emotionally believable as any of Assayas’ previous leads, but she also happens to have a capacity for communicating with spirits, a skill she utilizes to try and connect with her dead twin brother. While the script may be serious, it also contains its fair share of jump-scares, as well as the most outrageous, straight-faced inclusion of a CGI ghost I have ever seen.

Following the horror thread, the connection to technology is natural. Interest in the supernatural has historically fluctuated alongside revolutionary technology, which Personal Shopper directly references with the on-the-nose inclusion of an educational clip about telegraphs and séances. And horror has always embraced technology closely, usually incorporating its predilection towards malfunction to enable narratives. In The Blair Witch Project technology fails the fictional documentary-makers, whose compasses malfunction, whose cameras never capture anything, and as a result technology fails the audience, too. The demons in Evil Dead are summoned by a tape recording. Even during the golden age of slasher films in the late 1970s, the scares revolved around the phone line getting cut or the car-engine not starting. In 2016 the fear of technology failing has become fear of the unknown, which develops alongside the increasing complexity – and therefore mystery – of the technologies we dwell with and rely on.

We’re all familiar with the fear of surveillance and the terrifying concept of the singularity, but new specters have emerged to seize our imaginations, and are apparently potent sources of inspiration for filmmakers. The internet’s always been inherently nebulous, but increasingly our imagining of it and the language we use to define it is becoming more so. Like a ghost, the image of ‘the cloud’ invites fascination in its ephemerality and its mysterious quality. Most of us don’t know where it resides, who is surveying it, who is paying for it or what it really is.

Part of the new horror of technology is that has dematerialised and then suffused into our lives, following us wherever we go. We anxiously think of the cloud as hovering above and around us. Menacing text messages announce themselves in Maureen’s back pocket as she mopeds around Paris or trains to London. And then there are the poor souls in Lo and Behold who believe their bodies are literally sickened by unseen waves of radiation, a result of wireless networks. Sick bodies need exorcising, and Lo and Behold is studded with the language of religious horror. A grieving mother, speaking of the way the Internet allows people to shed their inhibitions and behave cruelly, talks of ‘the spirit of evil’ and the ‘anti-christ’ that is ‘running through everybody on earth.’ Lo and Behold is no horror film, but it’s imbued with a fear that’s rare for Herzog, whose documentaries are usually characterised by a mood of fascinated nihilism.

While Maureen attempts to connect with her dead twin, No Home Movie is also about connection. The documentary is, at face value, simply an examination of the relationship between Akerman and her mother. When Akerman’s home in Belgium, we see them interact in person; when she’s working in the United States we watch them talk on Skype. The Skype conversations in particular are universally recognisable in their halted flow, and in the confused awe of the elderly. Akerman yells into the laptop microphone to encourage her mother’s amazement: ‘there is no distance anymore!’

Though Akerman didn’t explicitly construct her film with ghosts in mind, their presence is still powerfully felt by the viewer as both women died soon after its completion. Akerman and her mother communed through the monitor, and now they communicate with us through cinema’s screen. While the barrier of the screen usually implies distance, this connection is at times uncomfortably intimate, especially when we watch her mother sleep in her armchair, or gradually become sicker and deteriorate. But despite its capacity for intimacy and the destruction of distance, the internet can still make ghosts of us all: we and our loved ones are apparitions in the skype window as much as the Akerman women are, the memories of ourselves three seconds past scattered in pixel form across the screen.

Memory’s a central theme in many of Akerman’s films, and memory can also help explain the overlay of ghosts and technology. In August we celebrated 25 years since the first website went public. Now the internet is truly out of its adolescence, and enough years have passed for us to have memories, even distant ones at that, of the web – and memories can become haunted. Herzog asked his subjects what the internet dreams of, and one answer was it dreams of itself; we could also ask what it remembers of itself. The web’s binary is no longer always crisp, but sometimes littered with cobwebs, gathering films of dust. Herzog points out that the early web were ‘dark days’ that can only be remembered, as most of it is lost forever. Otherwise there are forgotten abysses where countless lost files reside, files which, without metadata, essentially do not exist.

Looking beyond Europe, there are ghosts aplenty on the plains of northwestern China, where memory and loss are also explored in Hanyi‘s Life after Life. Here rural orchards have painfully met their demise in the face of the mining industry and locals can only hope that their houses don’t collapse, let alone long for an internet connection. While the technology in this case may not be digital, it’s just as transformative – albeit to more destructive effect – in the form of China’s industrialization. Like the internet, this industrial revolution has recently come of age and begun producing its own traumatic memories. In this context we’re presented with the story of Mingchung, whose son Leilei becomes inhabited by the spirit of his dead mother. As father and wife/son engage in a mission to replant a tree, they encounter many others – relatives, strangers, and ghosts – but no one is put out by the situation; fear is never factored in. The calm and universal acceptance of the Xiuying’s ghost rivals even the attitudes of those in the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, king of the low-key supernatural event.

In tandem with its core messages relating to the social devastation and alienation that results from rapid industrialization, the film speaks strongly to the memories of both people and place that are dead and falling into ruin, as well as to history. In one of the film’s most beautiful moments, a trio and their horse, who we realise are the ghosts of men centuries dead, watch from afar as the father carries his son up a hillside.

In Chinese folklore, ghosts are literally far more solid than their Western counterparts. They’re corporeal, opaque, not entirely beholden to the laws of this world but then not entirely exempt, either. So it makes sense that in Life after Life the technological context is more physical than the ephemeral internet, consisting of mining, of blowing things up, of massive housing blocks. These contemporary forces are in contrast to the ghosts, whose bodily labour recalls the past – be it through heaving a massive boulder down a mountainside or dragging an old tree across a landscape. These actions, and the ghosts themselves, act as an outlet for the immaterial sorrow that’s a result of a very physical technological threat. They’re history and memory and the past manifest, crying out against a destructive march into the present.

With a very different cultural history surrounding ghosts, and a less pragmatic attitude towards the supernatural, we might assume that the Western films need their own, more mystical conclusions. But it actually ends up coming back to the same surprisingly unperturbed and weighty place. These films may try to instill the poeticism of the unknown and the ungraspable into reality, but reality is heavier, more banal, and less mysterious than we’d like to believe.

In Personal Shopper, Maureen’s ghostly texts are revealed to merely be a very large, psychopathic German; the other spirits she hears are entirely psychological. And just like Maureen’s demons, the reality of the internet and of the cloud is quite different to what we expect or want – and far more solid. Our .mp3s, .docs and .jpegs don’t really float near us, up in the sky, but can be located in the middle of the American Midwest, or Northern California, or São Paulo, in the massive server farms that are required for cloud services to function. While the description of the digital migration as a process of ‘dematerialization’ may not be outright deception, then it’s at least a misnomer, and a misunderstanding.

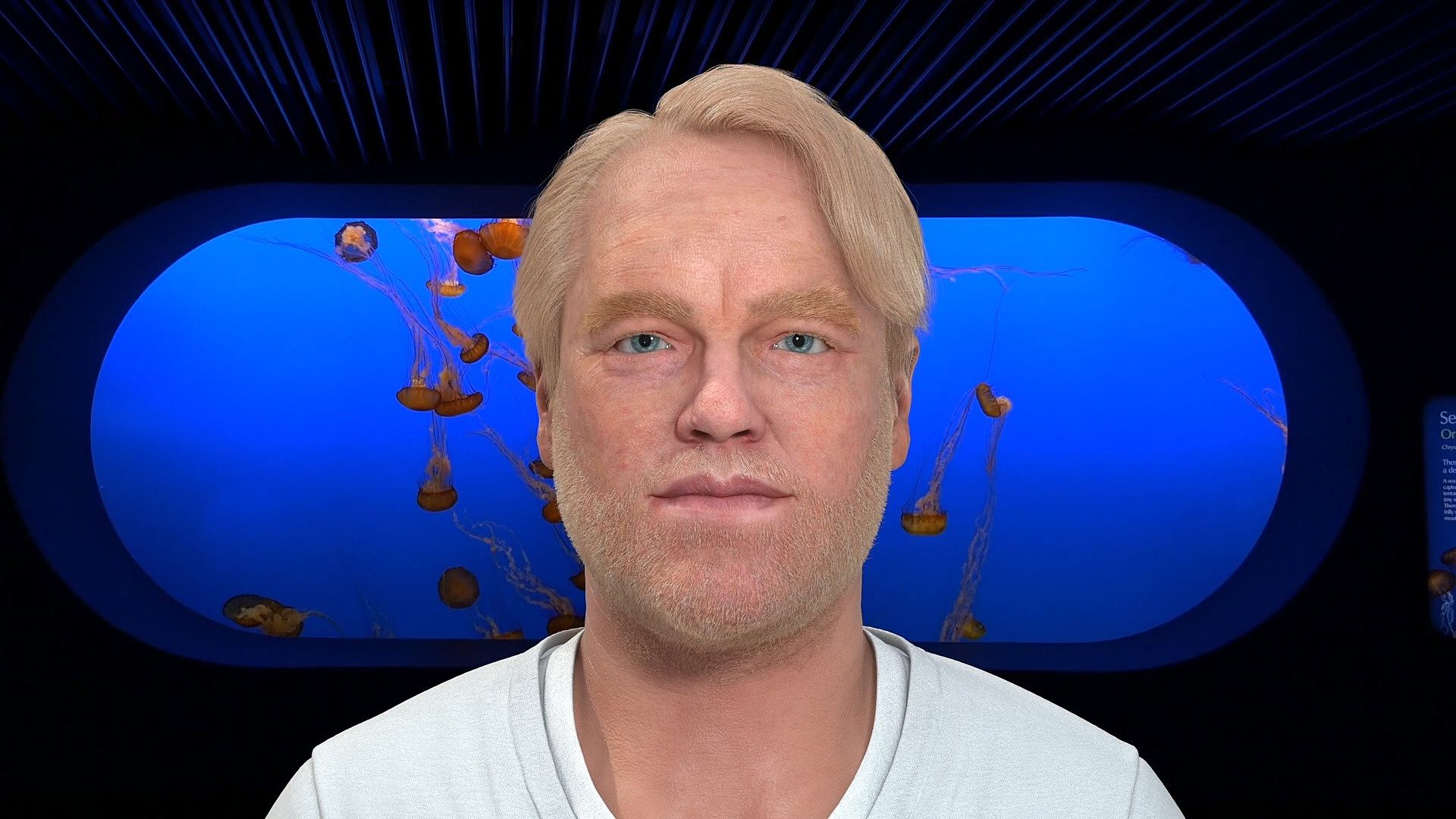

Art has the capacity to speak in an explicit language that more directly addresses complex ideas, and Cécile B. Evans’ video work Hyperlinks or it didn’t happen reveals some answers to the question of why we desire an immaterial and haunted internet. In it we’re introduced to PHIL, an HD render, or a “digital replacement … a bad copy, made too perfectly, too soon” of Philip Seymour Hoffman. He narrates the whole video, musing on death and grief, on his life on a server, acting as the protagonist of a work about different digital, non-sentient beings and their exploration of what it means for them to exist. It still feels raw to watch in 2016, but the work was released only months after his death in 2014. In fact, it is so prescient of the issues contemorary film is exploring two years later that one has to wonder if all these directors are fans of Evans.

Among many overlapping stories is the one of a grieving boyfriend who describes how, a year after his girlfriends’ death in a car accident, she starts contacting him. The first line we hear him speak is “my dead girlfriend keeps messaging me on Facebook. I’ve got the screenshots. I don’t know what to do.” As in Personal Shopper, we’re told it could all boil down to mental trauma, and thanks to that film’s suggestion that the dead boyfriend is messaging Maureen, it’s easy to believe that Assayas was directly inspired by Hyperlinks.

Throughout the work, PHIL converses with AGNES, the resident spam bot of the Serpentine Gallery website, and together they muse on their existence. So in one sense Hyperlinks is existential, but from the perspective of the lucky living, it’s also about desire. The work tells us as much through its inclusion of the Japanese hologram Hatsune Miko and the Youtube star Jemma Pixie Hixon. Both figures’ desirability is enhanced by their unattainability – Hatsune does not materially exist, and Hixon’s agoraphobia has stopped her from leaving her house in five years.

Nothing is more unattainable than the dead, and near the end of the work we see James Lipton comforting Amy Adams over Hoffman’s death on a talk show, and he tells her “we have him forever, thank heaven.” We desire our dead to live on, and we want technology to be infiltrated by ghosts because then we can have them forever. It’s a natural connection to make, to fill the digital with the ghostly, because if the internet is a vaporous cloud, if it is ephemeral and unknowable, then the assumption is it can house ephemeral and unknowable things.

These works reflect that we face a dismal, solid reality by imbuing it with more mystery than it can possibly contain, in order to stop us despairing – both at loss, and also at how unpoetic reality can be. Though it’s a lie, and though it’s ominous, we want the cloud to remain ephemeral, we don’t want to picture its server farms. Equally, we don’t want the possibility that Maureen’s ghosts are all in her head and although it’s terrifying, we’d rather that the dead girlfriend is messaging the boyfriend rather than he messaging himself. Instead, give us the internet’s spectral memories, its foggy metaphors, its promises of connection as well as its potential to obliterate. We choose the ghosts, say these works, which we have also created ourselves.