Hudson & Halls, Histories Intertwined

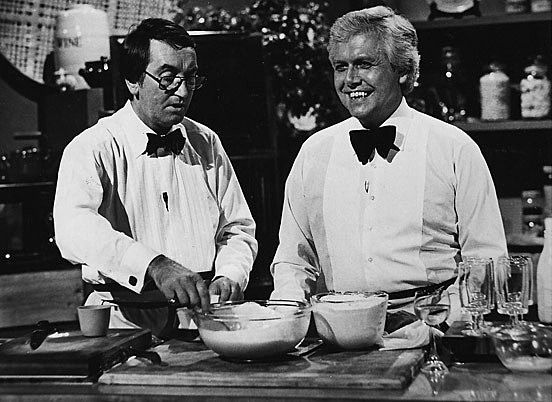

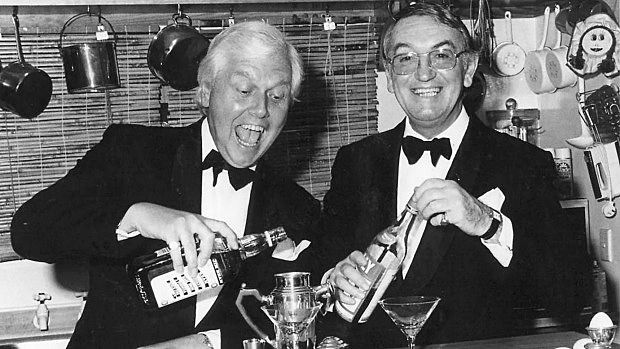

As part of Silo Theatre's world premiere season of 'Hudson & Halls Live!', we look back on the lives of Peter Hudson and David Halls, two iconic TV personalities from the 80s whose lives were inextricably intertwined.

The first time celebrity cooking duo Peter Hudson and David Halls recorded for television, it was 1975. TV2 had just launched and Marcia Russell had invited the pair to audition for Speakeasy, the afternoon show she fronted with Jeremy Payne.

Despite having consumed several “buckets of gin” the night before their audition (as Russell recalled years later in the Listener) the pair impressed everybody by whipping up a near-immaculate beef Wellington and the producer hired them on the spot for a series of six 10-minute segments.

They began recording at the station’s Shortland St studio four days later. The dish they’d chosen was kidneys in port. Straightforward enough, and all was going to plan until Hudson tilted their pan a little too enthusiastically, spilling port onto the stove and setting it alight. In a panic, Halls flung flour onto the flames, accidentally accelerating instead of abating the fire. It was a mad disaster, and the cameras kept rolling.

“The result was the funniest 10 minutes of television most of us had ever seen,” wrote Russell. “Even the floor manager (clutching a fire extinguisher and poised to save the studio from incineration) had tears streaming down his face.” Less to do with any potential damage, more to do with the way “Halls was ineffectually flapping [at the clouds of smoke] with a tea-towel while smiling reassuringly at Camera One.” Eventually the fire service showed up, and – demonstrating their natural flair as entertainers as well as their brazen adaptability – the pair turned the remainder of the segment they were filming into an instructional video on how to prevent kitchen fires.

It was this ad-libbed style that would define their entire careers: unpredictable, chaotic and often disastrous, but always performed with a wicked grin and quick wit.

Like so much of their life, their meeting was one of inescapable providence. Sixteen years before they started their first television fire, they were living on opposite sides of the world: two young, restless men itching to tread new ground.

Just out of London was David Halls, a 21-year-old who’d outgrown the council flat in Epping where he’d grown up. Having trained in foot anatomy, he was managing a small shoe store, determined to make a name for himself and aware he didn’t want to do it there.

Exploring his options, he nearly picked Canada but settled on New Zealand instead. “All that open air appealed to me,” he explained to8 O’Clock. “So I sailed for Auckland on the Rangitani.” It was 1959. He paid his own fare, briefly contemplated getting off in Australia, but finally arrived and embarked on a career as a shoe designer.

Meanwhile, in a shipping agent’s office in Melbourne, Peter Hudson had decided he wanted to live in London, but was becoming aware of the financial unattainability of the move. “I had a friend in Auckland,” he recalled. “So I decided to have a look at New Zealand.” Three years after David had moved there, Peter arrived to visit his friend Noel Cobine.

“I went out to the airport to meet Peter,” Noel recalls in the documentary Hudson and Halls – A Love Story. He’d planned a surprise party back at his flat to welcome his friend to the city. “When we arrived… all the lights went on and everyone yelled out ‘Hooray’, ‘Hello’, and all the rest of it.”

“Peter just walked into the room, absolutely flabbergasted at what was happening, a great big grin on his face… and just happened to look over at the mantelpiece.” Standing there was David, Noel’s neighbour, who had just happened to come over for the party. “And that’s how Peter and David met. It was an incredible moment, actually.”

The pair spent much of Peter’s three-week holiday together, and when he returned to Melbourne at the end of that trip, it wasn’t for very long.

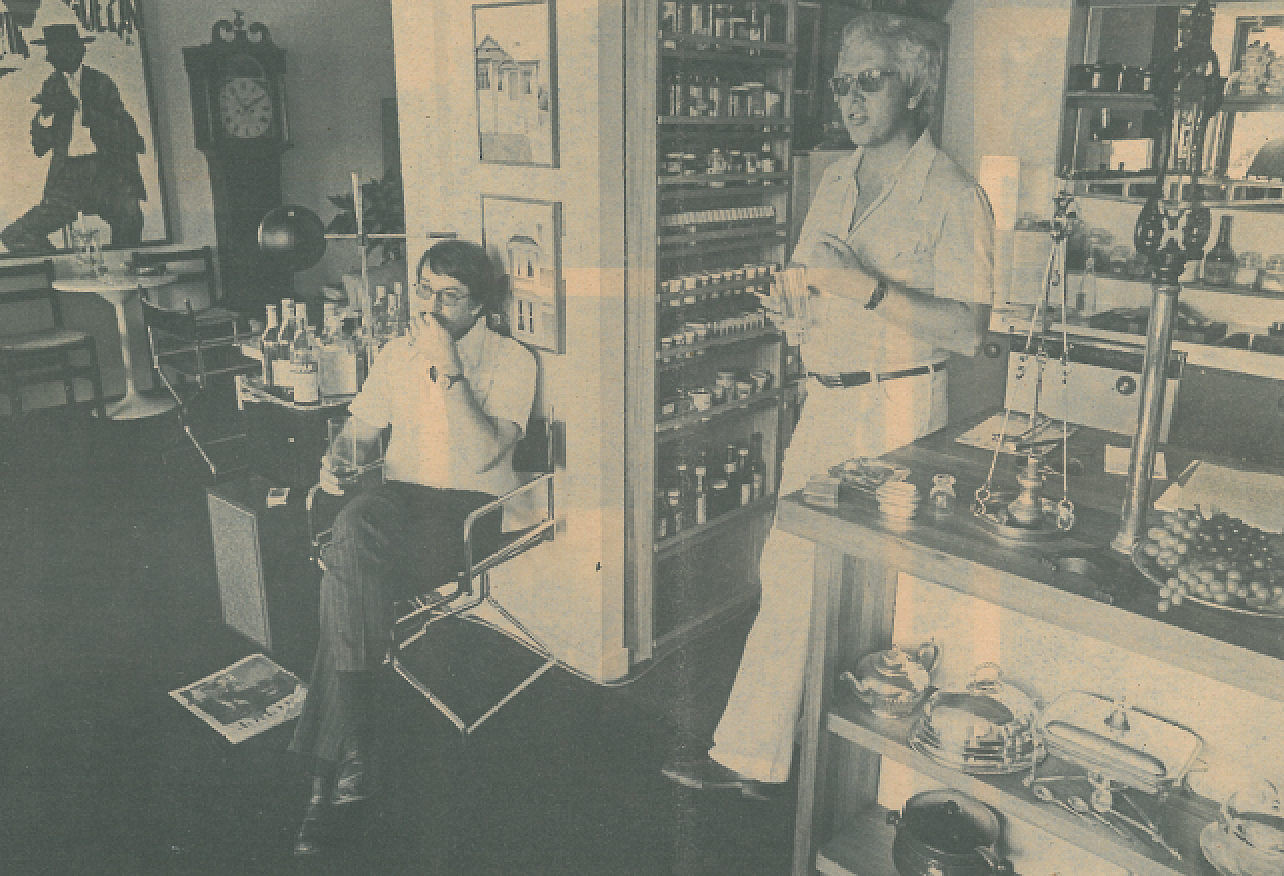

They were businessmen before they were TV personalities. Nine years after they met, the couple opened a women’s shoe shop in the Strand Arcade called Julius Garfinkle’s. “It sounded like a nice name to ring a till with,” Halls would tell people. Later, in the same stretch of shops, they opened one of Auckland’s first ice-cream parlours.

Wildly different ventures, their entrepreneurship underscored the pair’s tenacity, their willingness to take a risk, and their love for entertaining – and it was those same traits that led them to the little screen all those years later: they’d accepted a friend’s invitation to attend “a giant party” in Miami and had stopped on their way home to visit a friend in Sydney. While there, they cooked dinner for their hosts. “It consisted mainly of taking the tops off bottles,” Halls recalled, “There was much carrying on and laughter, and someone said: You two dopey so-and-sos should be on television.” It sowed the seed, which eventually – through a series of events, including recording a pilot and later meeting Marcia Russell at a party – led to their audition for Speakeasy.

The success of their ten-minute segments saw them continue long after the afternoon show folded, and a year later, TV2 programme controller Kevan Moore invited them to do a twice-weekly show of their own. It was to be called The Hudson and Halls Hour and would feature interviews, entertainment and, of course, cooking. “We turned it down immediately,” Halls told 8 O’Clock. “We had never been interviewers and we thought an hour was too long. We did not want to do it.”

But the allure of doing it overrode their every anxiety – and there were many, even once the show had begun filming. “I wanted to die,” Hudson told Tony Reid in the Listener, a year into their new show. “I thought I would throw up on camera and I literally needed two hands to hold on to a kitchen whisk.”

By 1980, they had moved to a late-night slot: half the time, twice the booze, and many a velvet bowtie. Their unscripted verbal slapstick and riotous, clanging cookery made them a ratings success and alongside their show they released a slew of cookbooks, hosted a morning radio show, opened a restaurant, and were awarded Entertainer of the Year in 1981.

“I must admit one thing,” Halls confided in an interview. “All this camping around on television is a hell of a lot more fun than the shoe trade.”

“Be a bit flamboyant, take a risk, don’t worry too much… you can always add more wine… or go out to dinner!”

- Hudson & Halls Cookbook (1977)

Nobody was doing anything like Hudson and Halls. Although other TV chefs of the time were similarly encouraging and pragmatic, they were also serious about what they did. Cardigan-wearing Graham Kerr recited recipes like poetry and fielded questions from swooning housewives about ways to cook cabbage (try roasting it with yoghurt and minced beef) and when to make your Christmas cake (May or June at the latest). Former DJ Des Britten encouraged viewers to strive for haute cuisine, and Alison Holst’s firm instructions made her our other-mother-of-the-nation.

Hudson and Halls eschewed their own authority. “We’re not chefs,” they’d insist, time and time again. “Chefs study cooking and get degrees and things. We never did that. We’re just cooks.” They drank. They burned their food. They celebrated imperfection. Hudson told the Herald: “We show people that we are fallible.” If they could cook, anyone could cook.

Above all else, they were for the people. They were natural entertainers, totally at ease with themselves. “They were doing reality TV before it really existed,” says Karen Kay, their former manager. More than simply instructional, Hudson and Halls fed New Zealand’s early voyeuristic desire to watch an adult couple bicker and drink while still managing to create something beautiful together. As in life, they were funny and volatile and outrageous and droll and viewers delighted in it.

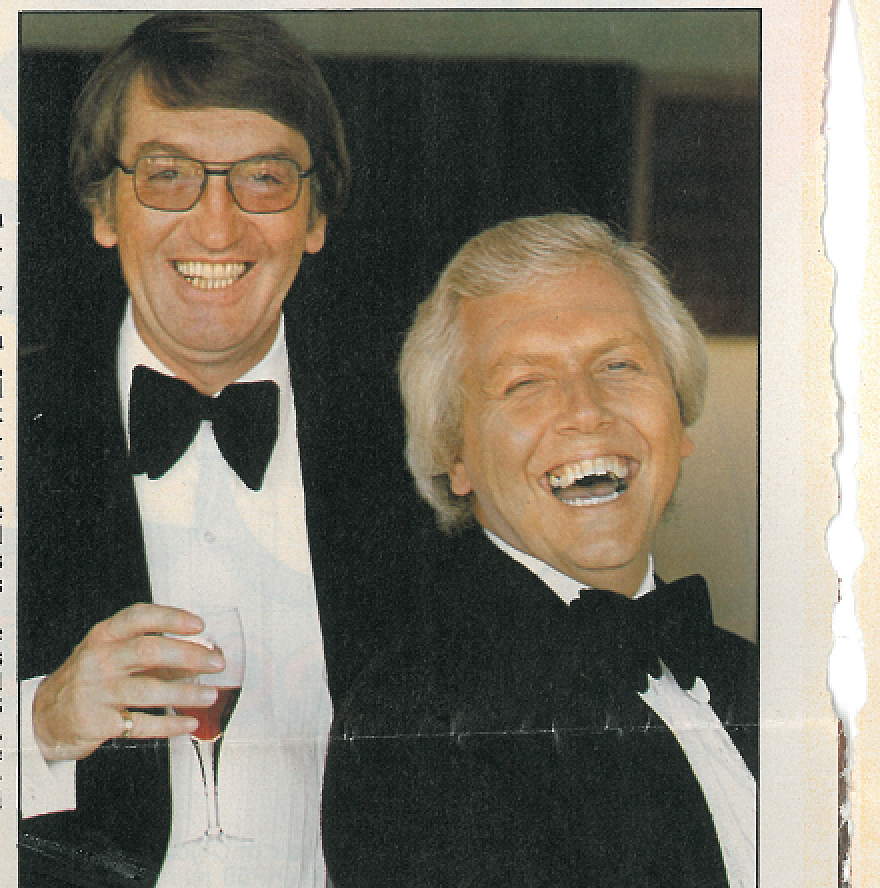

Although cooking wasn’t important to them, fame and success was. “They loved to be loved,” says Karen Kay. They thrived in front of a camera. “Especially David,” their former producer, John Carlaw, recalls in A Love Story, “David would light up like a Christmas bulb. He’d often walk around frowning and then when the camera was on – bang! – he’d be huge smile, and all the rest of it.”

So it was a huge blow when, in 1986, TVNZ cancelled their series. It had been 11 years – a more-than-decent run in TV time – but the pair were devastated. “We were told that we were dead,” Hudson told the Herald. It’s hard not to hear the bitterness in his voice. “[We were told] that no one in New Zealand was interested in us anymore.”

But New Zealand was just one country. They turned their attention elsewhere, and their unflinching confidence saw them sign with the BBC within the year. Although their earlier work was panned (Spike Milligan – one of the kinder critics of their show – called it a “failed Laurel and Hardy”), by the time their first season wrapped they had an audience of 3.5 million. Hudson and Halls: all set to take over the world, and yet still yearning for home. They set up another meeting with TVNZ, but the answer was still no, so they sold their house and moved to London for good. Bravado aside, the pair were sincerely sad to leave, and footage from their final Radio Pacific show sees Peter staring down at his lap, chin quivering, trying his hardest not to cry.

*For us, their show also offered a window into a different kind of world. Although their love wasn’t a political one, it nevertheless existed in the public eye during a time when homosexuality was illegal and rarely spoken about.

“It seems to me that most New Zealand men are gentler and more tolerant than most people realise,” Peter told the Listener in one of the only interviews their relationship was discussed. “I wouldn’t say we’ve been instrumental in breaking down sexual prejudice… but we’ve never suffered an unkind word in that area.”

Truckies and wharfies and older women were cited among their greatest fans. They loved their public, but more than anything, they adored each other and achieved what very few couples can: they worked together, and they actually wanted to keep working together. Beyond their squabbling and their tantrums, they were devoted to one another. Much of their time was spent in each other’s company, whether it was entertaining friends, looking after their sheep on their Leigh farm, presenting their show, or driving through the countryside illegally (neither had a license) in their silver and black Bentley.

Their existence was so intertwined that it was difficult to imagine them apart, and when Peter was diagnosed with prostate cancer it suggested an inconceivable future. After undergoing radiation therapy, he seemed to bounce back, but a year after leaving New Zealand it returned – more aggressively, this time – and in 1991, he died. It was completely devastating for David. Alone in London, he changed his surname to Hudson-Halls, and for the next fourteen months he continued on: he went out for dinner, he visited friends, he even made a handful of muted appearances on TV, but none of it was the same without Peter by his side, and on the 24th November 1993, David’s body was found in his apartment with a picture of Peter held tightly in his hand.

“I don’t want to grow old and alone,” he wrote in his diary the night he overdosed on Peter’s morphine pills. “Without Peter I don’t want to go on – he was my life, and I have no regrets. I love him now as much as I always did and I want to be with him for all eternity.”

*David Hudson and Peter Halls were together for thirty years. They are remembered by their friends and colleagues for their generous spirit and playful extravagance; for their incredible ambition and their unrivalled hard-headedness; for the bottles of rum they hid around their set; and for the love they had for each other and for those they got to entertain.

“One of my fondest memories,” says their friend Jan Cormack, “is when they appeared at the hospital the day after my son Jamie was born.” She’d asked them to be Jamie’s godparents, so they arrived “armed with a candelabra, a tablecloth, caviar, crayfish, champagne and set it all up on the floor of my room. The hospital staff loved it.”

“We also had heaps of fun playing charades with Elton John,” she adds, almost as an afterthought, “who they were quite friendly with in the early days when he came to New Zealand.”

For an entire generation, they’re remembered for their show: for the way they embraced being themselves – flaws and all – and the way that they showed us that there’s no such thing as failure: fires are just an opportunity for a spiced-up segment on prevention, and if you burn that cauliflower soufflé, all you need to do is smile, pour another glass, and turn the damn thing to soup.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Silo Theatre, who cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

In celebration of Hudson & Halls, we are hosting

in collaboration with Silo Theatre and Auckland Live

A Hudson & Halls Dinner Experience

A three-course Hudson & Halls-inspired dinner with matched wines

on the stage of The Civic Theatre

followed by Hudson & Halls Live!

5.30pm • Saturday 14 November

More information here

Tickets available through Ticketmaster

or by calling Silo Theatre on 09 361 1551

Read our review of Hudson & Halls Live!

Hudson & Halls Live! runs at

The Herald Theatre

from November 5 - October 31

Buy your tickets here