Give and Take: Imogen Taylor's 'Glory Hole' and Political Camp

Owen Connors picks at the roots of Imogen Taylor's recent works

When I first encountered Imogen Taylor’s most recent solo show, Glory Hole, at Micheal Lett Gallery late last year, the most confronting aspect wasn’t the name, but the dramatic change in scale. The small canvases of Taylor’s past shows have been replaced by large, low hung stretched jute works, expressing both the confidence and provocation that placing or taking a cock through a hole in a wall would suggest. This going big, as with most female artist’s size decisions, gets easily rendered as a theatrical enactment of macho modernism, the Mitre 10 MEGA’s “big is good” mantra to New Zealand’s aesthetic sensibility taken to the point of self-parody; a playing around with the notion of becoming erect.

Yet, despite this playful gesture of identity-based critique of the art world, there is value in interpreting Taylor’s developments beyond a reading that relies upon traditional notions of lack,that practitioners outside the ‘White Male Artist’ model are subservient to (pigeonholed, perhaps, rather than gloryholed).

Producing big ‘abstracts’ as a rejection of the status quo within the art world seems such a crude interpretation of Taylor’s work; yet looking to the ways in which queerness, as both a sexuality and defiance of normative ways of being in the world, functions beneath the surface gestures of these new paintings exposes a complex interaction of this body of work with identity.

A recent article I came across questioned Taylor’s legitimacy in participating in a queer conversation, deeming her “zombie formalism” irrelevant in the face of historical engagement with the HIV crisis. It is this critique that I affectively spring from, unpacking the subtleties of style across Taylor’s oeuvre to defy conceptions of the apolitical that sometimes accompany an engagement with aesthetics, where the decorative is depoliticised. Moreover, Taylor is looking at the interactions between existence and expression in ways that are both provocative and practical.

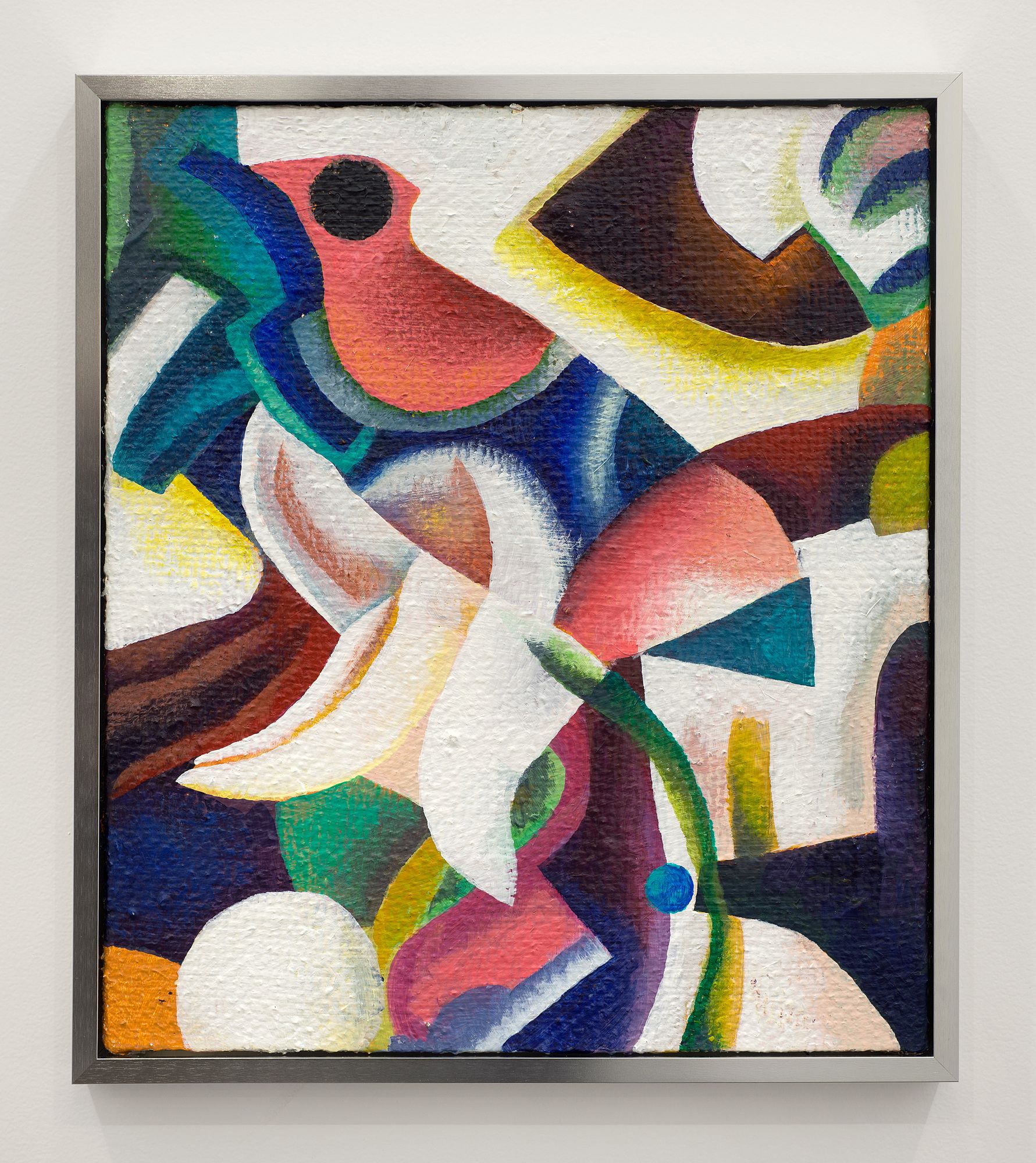

When approaching these new works in relation to Taylor’s past practice, one can immediately sense a consistent use of collage. Early works merge paint with the likes of string, straws and sponges, creating cheekily representative and symbolic forms out of the ephemera of the everyday. In these more recent works, the three-dimensional collage of objects has been superseded by the quotation of various styles and forms instead, simultaneously producing and disrupting Taylor’s compositions. Collage persists, in the form of an assemblage of painters from New Zealand’s canon.

Although the visible influence of history is customary in painting practice, Taylor’s directness and discursive sourcing suggests a process more akin to copy and paste, a trawling through art history to produce an over-saturated pastiche. This is hardly a criticism, given the breadth of the source material, as this cut–and-paste processing manages to merge disparate approaches to painting, from Philip Clairmont’s jarring expressionism and intentional entropy, to Rita Angus’ flattened and sharp modernist figures, enriching these works through their outward and backward reach.

The tradition of collage Taylor’s playing with here has often been rendered subordinate to the hegemony of painting. It is seen as an unassuming means of production that does not rely upon significant capital investment, instead sourcing material that plays to alternative systems of value. The introduction of collage into the medium of paint destabilises the hierarchy we prescribe to specific mediums.

It’s a decision that differentiates these works from their painting influences and their taxonomy - refusing to occupy a position within a binary of high and low, experiential and theoretical, simultaneously producing proclamations of beauty by seasoned patrons and notes in students’ handbooks proclaiming “Imogen Taylor = Ugly painting.”

This use of collage also engages with its sources in a manner that defies traditional art historical enquiry. Each composition contains elements that suggest a nod to others, communicating across time in a manner that denies a narrative of progression. Stretched jute and curvy caricatured forms say hello to Tony Fomison, muddied modern colours and floating forms seem to acknowledge the still life of Frances Hodgkins, whilst over-worked blocks of rough acrylic, trying to merge like oils, pull in Colin McCahon’s Northland Panels.

The reverence to this process of production is in some way tied to an interest in how the pastiche can operate as critique. Rather then purely working with the signifiers of the past (such as size) to establish a critical historic relationship through reactionary appropriation, Taylor’s practice uses pastiche to actively deny the avant-garde, to disregard narratives of bettering and advancing as a model of artistic development.

In fine art schools, the notion of being critical is often saturated with psychoanalytical nuances; ‘Daddy problems’ addressed through rejecting and appropriating the forms of the past issue forth as models are taught which seek to knock the older generation off the pedestal. In Taylor’s practice, pastiche denies its own path of least resistance. Past practitioners concerns such as notions of abstraction and light are pushed with an attitude of homage and the works themselves, although constituting an individual style are heavily reliant upon their influences.

This process of pastiche is often denied any critical inquiry as it is perceived to be simplified to homage and aesthetic appreciation (which is not strictly a negative experience). However, it does feed into readings of the work that reduce artistic intent in favour of the kind of accusations of “zombie formalism” that I am addressing. In fact, the notion of collage as a language and method of communication is one which is intended to recognise its destructive quality, rather than one that aggregates or curates the past.

In fact, for Taylor and many of us, the past isn’t just a foreign country, but an entirely alien notion. There is something distinctly yet subtly queer about Taylor’s use of pastiche if we question how time may function for the queer body - denied the hegemony of reproduction, disengaged with its ancestry. Both lockstep reverence and rebellion are normative responses. The queer as a floating identity, seeking out alternative familial relations, may begin to chafe against the ‘family’ art model and seek a different way to engage with the past and the future.

The process of cutting and pasting starts off by destroying the original meaning of the source material, but also it produces outputs which abstract the originally representational, and Taylor’s source material relies upon a balancing of abstraction and representation. Her quotations of various artists pick up on this notion of abstraction in various ways, from a fracturing of the form akin to cubism, to an altering of perspective that denies the ordinarily mimetic nature of painting.

One consequence of the collaging process contributes is a formal reading of Taylor’s work as a set of strictly abstract references. But if Taylor has engaged with her influences within pastiche, we should engage with them too: we should insist on locating that representation beneath the formal destruction of collage. We should investigate what these influences speak to, and what the ramifications are of destroying the representational.

Finding representations in the work isn’t all that difficult, as it still insists on presenting the figurative – and despite the destruction of collage, it does so often, and in surprising ways. The gallery’s press release for the show insisted these works consist of “human forms and suggestions of bodily functions – penetration, secretion and taction – that push through her layers of abstraction.”

This can be seen within Pelvic Floors, as suggestions of a phallic form protrude from the left of the painting as organic silhouettes overlap at eye level - a multiplicity of thighs and bums, or potentially just a scenic view of New Zealand’s hilly terrain.

The release goes on to discuss the “erotics…not for their anonymity or discretion, but rather their resolute presence.” However, as a result of the destructive nature of Taylor’s use of collage to produce these compositions, this sensual presence is not purely reliant upon form, but also a modern palette which wilfully merges the sexy and grotesque of the colour wheel – not to mention the title to the exhibition itself, which rejoices in turning undertones into overtones.

This collage as language, despite its role in abstracting these erotic scenes, also builds them. Different styles and approaches to producing form create a polymorphous body in Taylor’s work, albeit one we are denied a clear picture of. The language of collage becomes akin to a performance or articulation, describing and acknowledging a representational form whilst allowing the structure of communication to disrupt and complicate it.

Inarguably, this is a personal and political gesture. There is a pervading culture of taboo that still exists around queer female desire, and female desire in general. But Taylor’s structure isn’t abstracting this desire to get one over the past – in fact, it plays to a legacy of dancing around judgement and censure. There is something akin to Caravaggio in these works, as his use of religious and historical motifs to present the homoerotic lingers as a trope of queer sexual expression.

As in that case, the active abstraction of sexual subject matter allows for its acceptance in wider society: works may be discussed for their colour, their texture, their composition, their formal attributes, rather then the directly confrontational ‘message’ that lays beneath.

Yet as the gallery has suggested, this does not just concern “anonymity or discretion”. The emphasis on Taylor’s process as being akin to language situates a mode of sexual expression within structures of everyday communication.

What it recalls to me most is that most veiled of inter-personal relations, the complex, multi-sensory language structure of flirting. Its suggestive glances, the jokes and innuendo and allusions to attraction all carry particular resonance in queer relationship formation, in environments where instigation and presentation of flirting carry with them dangers beyond rejection – shame, ostracism, and violence. The “resolute presence” of the sexual in Taylor’s work plays to this queer sensibility, and can appear on first blush to pull in opposite directions – a need to disguise one’s sexual practice whilst constantly remembering and celebrating its role in differentiating oneself from heteronormative society.

So this reading of collage in Imogen Taylor’s practice draws distinct connections to a queer way of being in the world, both in the form of pastiche in relation to time and in alternative language structures when addressing sexual desire. This can be called, tentatively, a queer sensibility, a way of feeling whose presence and influence is often hard to pinpoint.

There is, however, another sensibility that I have initially avoided attaching to this work – camp. The camp sensibility, as outlined by Susan Sontag’s seminal 1964 essay “Notes on Camp”, presents us with a virtual checklist with which to inspect Taylor’s work in fulfilling this feeling. Sontag identifies camp as an aesthetic of “artifice”, a “marginal” and largely “decorative” set of traits and affectations that “neutralizes moral indignation [and] sponsors playfulness.”

This description of camp, however, appears to sit at odds with a sentimentally political engagement with Taylor’s work – or other work that involves pastiche, frivolity, and a certain level of artifice. In Sontag’s view, camp exudes an attitude of the “disengaged, depoliticized – or at least apolitical.” Emphasis is placed upon the “extravagance” of camp, the work “in terms of style”. She stresses that “pure camp is always naïve” – but if we take her at her word, we seemingly deny ourselves the potential to discuss this element of Taylor’s work as part of any intentional queer discourse.

This denial of queer association with camp has arisen in recent theorising and artistic practice in the camp camp. Chris Sharp’s “Notes on Neo-Camp” (2013) – a group show curated at London’s Studio Voltaire taking Sharp’s essay “Camp + Dandyism = Neo-Camp” as a starting point - attempted to isolate this sensibility as something “post-homosexual”, a formal style now “divorced from its political, predominately homosexual, subcultural origins.”

Camp, within Sharp’s reworking of the term, comes to be described as a “gay heritage style”, which, although recognising something inherently queer within camp’s historical use, disavows contemporary camp practice from personal queer experience and an ongoing political agenda.

If I stray from a formal reading of her practice, Taylor’s treatment of a camp sensibility can be distinguished from Sharp’s. Instead, one can recognise that the queer sensibility in Taylor’s practice runs parallel to readings of a camp sensibility. The structures of language mentioned earlier that Taylor uses to abstract the sexual operate with the same sensibility as the theatrical and exaggerated nature of camp. Sontag notes that camp is the “love of the exaggerated, the "off," of things-being-what-they-are-not.”

Within Taylor’s practice this “things-being-what-they-are-not” manifests as both discreet involvement of queer subject matter through abstraction, and models of flirtation that talk around queerness. It is based in understanding the role one occupies in the world, and the impact of that in aesthetic outputs.

Locating this in Taylor’s practice is a reminder and recognition that the theatrical structure of camp may pull upon how the queer body is forced to behave in heterosexual society. Taylor’s engagement with history, and the subsequent queer sensibility attached to this, also feed into Sontag’s - noting that “camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as "a camp," they're enjoying it.”

I realise that hitching a queer sensibility to a camp sensibility when looking at Taylor’s practice is in many ways limiting. The scope of camp, as with the scope of so much queer subjectivity, is diverse and complex.

But in connecting the two, and arguing that there is something inherently queer about camp, I hope to continue the question of how identity politics function within the aesthetic realm. Taylor’s use of the sensibility is less about any appropriation of a political or “historically gay style” – instead, it’s more akin to an understanding of alternative ways of living and being in the world. Looking at aesthetics in such a way hopefully empowers reading of the complexity of experience at play in her work – it’s a fine example of how art that operates within identity politics may use alternative styles and technique, not just didacticism, to undermine the status quo.