Integration and Denial: Reading James Baldwin after Don Dale

Orlando Edmonds on what James Baldwin still has to teach the South Pacific's colonial states

Footage of young Aboriginal men being tortured at a Northern Territory corrections facility put the Australian public into a rare moment of shame and reflection last year. Was it just one regional government's racism, or a whole system set up to fail and oppress again and again? Orlando Edmonds on how those would like to make good on the past would do well to read some James Baldwin.

They are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.

James Baldwin

From ‘A Letter to My Nephew’

The Progressive

December 1962

On Facebook, Darwin’s Don Dale Juvenile Centre is listed as a ‘landmark’. It has garnered an average rating of 1.7 stars out of a possible 5. Unlike Sydney’s Fort Denison or Wentworth Gaol, both host to steady streams of tourists, it is perhaps reasonable to assume that the lesson offered by this particular historical attraction is, as yet, still to be fully appreciated.

Last winter, Don Dale ploughed its way through headlines as Four Corners: Australia’s Shame, ABC’s exposé of abuse in youth detention, sunk down our newsfeeds. Many were shocked by footage of Aboriginal children being tear gassed and stripped naked. However, campaigners and ex-staffers each met it with weary frustration — they’d been aware of the situation for some years, and many had raised the alarm when a 15-year-old boy took his own life in his Don Dale cell after stealing less than $100 of stationery. That was in February 2000. Despite what we might like to imagine, abuse and corruption in the prison system is nothing new.

And in fact, Four Corners detailed plenty of instances of where that abuse and corruption was ignored. Warnings that training and reform were needed weren’t taken heed of when the they were given by the previous (2008-14) Northern Territory Children’s Commissioner, Dr. Howard Bath. He said there should be a public inquiry in 2014, but no report took place. The Northern Territory government ministers said it would be too expensive and undertook an internal review of their own instead. The current Commissioner, Colleen Gwynne, conducted a report in 2015 in which she concluded that Don Dale’s regimen ‘was not targeted towards good and responsible management of young people in detention’ but rather towards the ‘use of force’. And yet no substantive action was taken: there was a superficial renovation of the building, and the children were temporarily moved before eventually being put back in a new, revamped Don Dale. There, solitary confinement continued for weeks on end.

Neither has abuse nor institutional warnings been confined to Don Dale or the NT. Mick Gooda, the NT’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, is one of the people who's been trying to have stories like these told for a while now. Thankfully, in August 2016, after some anxiety about how deep the rabbit hole would even be allowed to go, he was appointed Commissioner for the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, along with Margaret White. Hearings started in October 2016, and the report is due in March 2017. We’ll see where it takes us, I guess.

Even though Don Dale cannot be understood exclusively as a racial issue, you cannot understand Australian race relations without paying attention to the justice system. As we know, history has a tendency to repeat itself.

Just in this last year, according to the Corrective Services, Australia publication on the the Australian Bureau of Statistics site, the average daily number of full-time prisoners has incresed by 8% (2,736 prisoners) and community-based corrections orders have increased by 12% (6,910 persons). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners represented 28% of the total full-time adult prisoner population, whilst accounting for approximately 2% of the total Australian population aged 18 years and over. The national average daily Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander imprisonment rate for the June quarter of 2016 was 2,373 prisoners per 100,000 adults — that’s 5% up from the June quarter of 2015, just one year prior.

*

Australia – indeed, colonial nations in general - always had a prison complex, so to speak, and it extends from the multiple forms colonisers employed to deal with ‘otherness’ – to negate it, ‘fix’ it, or contain it. Since 1788 and the original contact between the indigenous Australians and the British, the problem of de-othering, or ‘civilising’ the native — the Black man, the savage — has been central.

Under instruction from the Crown that relations should be made with the indigenous people they came across, the first Governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, took to kidnapping Aboriginal people so that he might make sense of them and their difference. SBS’s documentary series First Australians documents these events, specifically Phillip’s capture of Bennelong, a charismatic and senior member of the Wangal clan. Out of a mutual curiosity and despite trepidation, the two men formed a relationship. Bennelong learnt English and spent much time in Phillip’s estate, eventually also travelling back with him to Britain. However, on returning home, Bennelong found himself estranged from his family and displaced in his community.

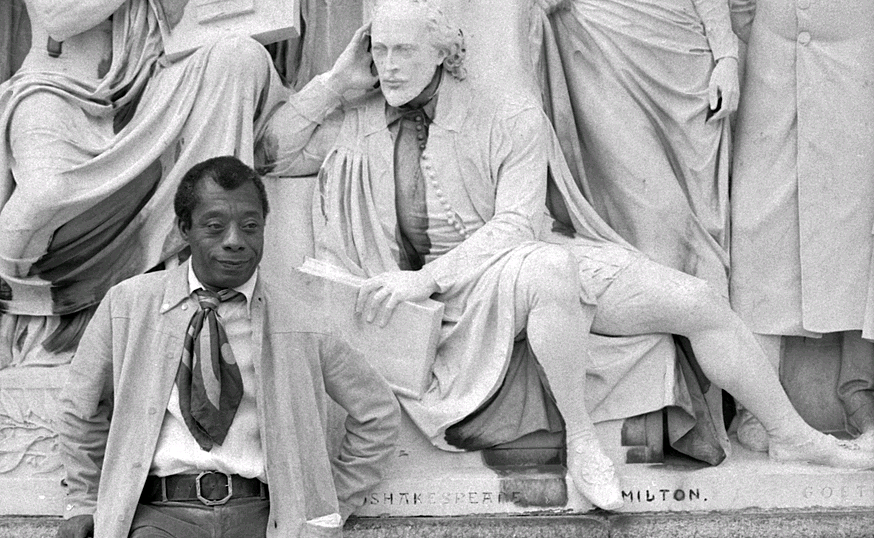

Half a world and over 150 years away, estranged from and displaced in his own country throughout his life - for his race, for his homosexuality - James Arthur Baldwin insisted on the right to criticise America precisely because he felt love for it and because it was his home. His double consciousness as a Black American and a descendent of slaves produced the conflict of identity that formed his 1963 non-fiction work, The Fire Next Time.[1] It is from this position that the book thinks through the social construction of Blackness and the consequent violence it justified.

The problem, perhaps, is the lack of any initial radical vision. Perhaps, in part, this is because of a top-down and paternalistic origin. The decision to eschew ‘long-term aims’ commits to discrete and worthy projects in health, education and employment, but not meaningful structural reform in the long-term. Without (re)assessing our ends, ‘new approaches’ can just end up meaning new approaches to reaching the same mistake.

Though Baldwin was writing during civil-rights-America, his concern with the vocabulary that shapes and accompanies the top-down maxims of race relations is still (unfortunately) relevant today. The situation faced by contemporary Australia is presaged in Baldwin’s concerns with the paradoxes of Black consciousness , and indeed, most powerfully, the contradictions of colonising whites and their ‘benign’ interventions. Baldwin is one of the foremost and most prescient critics of what we sometimes call the narrative of respectability and the way it dictates the basis on which white society in Australia or America gives or revokes its favour .

And yet, as far as his oeuvre goes, The Fire Next Time is criticised by some as a bastion of Baldwin’s early tenure in the ‘white liberal establishment’, where a humanist, even ‘spiritual’ apologism clouds the sense that there’s something fundamentally superficial about merely re-aligning the color line. That is, we don’t quite get the full-blown radical, Richard Wright influence (which he initially disavowed) until later in Baldwin’s career. Nevertheless, The Fire Next Time introduces and fiercely works through some key questions concerning motivation and language used to describe racial violence (and its proposed palliatives) in America. A contemporary reading alongside colonial Australia's own choice of official language is telling.

*

Australia has a rich history of terms used to imagine the organisation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders within (or, indeed, without) white society. The Australian Law Reform Commission’s Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws, for example, published in 1986, details the shift in thinking from ‘protectionism’ and ‘assimilationist’ policies to ‘integrationist’ notions, and eventually, ideas of ‘self-determination’ and ‘self-sufficiency’.

As it happens, the report itself is proof that, at least by the early 1980s, some government officials were quite aware of the complexity and dynamism of the issues they faced. Consider, for instance, this section, that talks about wanting to avoid ‘one-word descriptions of complex policies’:

The term “integration” was sometimes used by the critics of the assimilation policy to denote a policy that recognised the value of Aboriginal culture and the right of Aboriginals to retain their languages and customs and maintain their own distinctive communities, but there was a deliberate effort on the part of the Commonwealth authorities to avoid one-word descriptions of complex policies, and to focus on developing new approaches to problems rather than on long-term aims.

Here, in the paperwork, we find a considered narration of how one navigates the obstacles to justice, and yet, in practice, we see inconsistencies. The problem, perhaps, is the lack of any initial radical vision. Perhaps, in part, this is because of a top-down and paternalistic origin. The decision to eschew ‘long-term aims’ commits to discrete and worthy projects in health, education and employment, but not meaningful structural reform in the long-term. Without (re)assessing our ends, ‘new approaches’ can just end up meaning new approaches to reaching the same mistake.

Baldwin was highly suspicious of the ‘integration’ consensus in the United States. He saw that integration into a broken system only led to the opportunity to be exploited in a greater variety of ways. There was neither ‘reason to suppose that white people are better equipped to frame the laws by which I am to be governed than I am’ nor to deny that, as history testifies, ‘white people cannot, in the generality, be taken as models of how to live’. You had to envision a different social formation to enter into, because the old one is what produced your poverty in the first place.

Against the prospect of such fundamental change, Baldwin explains in ‘Letter from a Region in My Mind’ (the second composite essay of The Fire Next Time), white society reproduces itself by nurturing the assumption of its worth:

White Americans find it as difficult as white people elsewhere do to divest themselves of the notion that they are in possession of some intrinsic value that black people need, or want. And this assumption — which, for example, makes the solution to the Negro problem depend on the speed with which Negroes accept and adopt white standards — is revealed in all kinds of striking ways, from Bobby Kennedy’s assurance that a Negro can become President in forty years to the unfortunate tone of warm congratulation with which so many liberals address their Negro equals.

The idea that ‘white standards’ are those to which Black subjects should aspire (while being encouraged to maintain some arbitrary and perfunctory measure of traditional culture) presumes that these are worthy standards in the first place. Though this is characterised as his ‘liberal’ period, Baldwin makes a radical turn away from some abstract notion of ‘integration’ by drawing attention to the bias of the word as it was used. Integration of Black subjects into a white society built on the subjugation of Black bodies is a logical impossibility. Like the paradox of time-travel, the word erases the history that produced it.

‘For the horrors of the American Negro’s life there has been almost no language’, Baldwin insists, recognising, therefore, that ‘the power of the white world is threatened whenever a black man refuses to accept the white world’s definitions’. Imagining futurity without structural violence, a future that is just and sustainable, requires you to use language that doesn’t deny the past on which it stands.

The Northern Terrirtory Intervention of 2007, since rebranded as the friendly-sounding ‘Stronger Futures’ policy, unfortunately seems to project a different future, characterised by stronger cycles of entrapment and more constellations of white definitions. Introduced as a response to the Little Children are Sacred report, seen through by the Northern Territory Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse in 2007, the Intervention was effectively a series of curbing policies whereby the federal and state governments could ringfence the rights and benefits of individuals deemed to be a threat to children in Aboriginal communities. Subsequent evaluations of the intervention deemed it an unmitigated failure, and the community leaders that were supposed to have been included in the decision making process ending up feeling excluded and angry at the outcomes. Not surprisingly, they deem them to be punitive and disempowering.

Acceptance, therefore, also means confronting white society’s heritage in settler colonialism in general, in order to know where we stand and how we can look ahead. ‘To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it’, Baldwin writes. ‘It is learning how to use it’.

Julia Gillard’s government introduced Stronger Futures rebranding in 2012 as a corrective to what was seen as the Howard intervention’s most draconian aspects, but it has since come in for criticism in its own right. Most damningly, the 2016 Review of Stronger Futures measures explained that the ‘current approach to income management’ is not a ‘human rights compliant approach’. As in the wake of Don Dale, and in a seeming banner year for white grievance, we'll have to see how this shakes out. Will we get minor course corrections, or a radical reversal of bad policy?

Beyond integration, Baldwin would have us scrutinise the terms that seem the most harmless. A key word for him is ‘acceptance’, which he sees as operating in different ways. The first of these pertains back to integration, to ‘being accepted’:

There appears to be a vast amount of confusion on this point, but I do not know many Negroes who are eager to be ‘accepted’ by white people, still less to be loved by them; they, the blacks, simply don’t wish to be beaten over the head by the whites every instant of our brief passage on this planet…

The second kind of acceptance is introspective and retrospective:

…White people in this country will have quite enough to do in learning how to accept and love themselves and each other, and when they have achieved this—which will not be tomorrow and may very well be never—the Negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed.

Acceptance, in this case, means confronting history — both personal and collective. It means confronting a fear of ‘the other’ and a fear of difference as it poses, in its alterity, a threat to identity or to ‘life’, as such. Indeed, Baldwin theorizes,

perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.

The ‘Negro’ is itself a reminder of slavery and the death embedded in it. Figuratively — in the form of social death, or exclusion from white society — and literally — through lynchings, deprivation and abuse. Acceptance, therefore, also means confronting white society’s heritage in settler colonialism in general, in order to know where we stand and how we can look ahead. ‘To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it’, Baldwin writes. ‘It is learning how to use it’.

The violence that made the New World had to be normalised by the ‘story’ that Black bodies were subhuman. What Baldwin asks us to recognise is that ‘change’ can occur only when this story is accepted to be false. And when he speaks of ‘change’, he means it ‘not on the surface but in the depth — change in the sense of renewal’. This requires acceptance not as integration into the old ways, but as letting go of them:

[…] Renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to be constant that are not—safety, for example, or money, or power. One clings then to chimeras, by which one can only be betrayed, and the entire hope—the entire possibility—of freedom disappears.

What Baldwin sees is the problem of trying to be accepted into a system of psychological and political denial. ‘To defend oneself against a fear’, he writes, ‘is simply to insure that one will, one day, be conquered by it’. The past always comes back.

*

And when undertanding official policy towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – its failures, and its abuses – it’s necessary to remember that Australia is shackled by its own chains of denial, even in its glimpses of well-intentioned official strategy. Historian John Harris captures this enduring climate in his article, ‘Hiding the Bodies: The Myth of the Humane Colonisation of Aboriginal Australia’, a piece penned in response to right-wing commentator Keith Windschuttle’s devout genocide revisionism, popularised by his book series entitled The Fabrication of Aboriginal History. Both historians make claims about the number of Aboriginal people killed during the invasion of their land but, for our purposes, what’s significant is less their estimates than the method of counting them.

In Harris’ words, Windschuttle privileges the ‘forensic’ approach to history, ‘restricted to what is actually stated in the written records’, whereas Harris tries to account for verbal records and the stories passed down through generations. Windschuttle’s methodology is problematic, Harris explains, because ‘restricting the truth to what has been written must by definition be biased in favour of the victors, the richer and more powerful’. Our ability to understand the nature of the dispossession and disempowerment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is limited by our inability to hear the stories in the first place.

The normal ways of counting a political body or affording and upholding their right to a higher standard of living, eventually fail, as they cease to interrogate the basic assumptions built into the lens that forms their vision. The losers are always already outside the picture’s frame, or just blurs in the background.

French philosopher Jacques Ranciére sees precisely this conundrum of ‘how to count’ as defining the nature of politics itself. For him, politics is simply a way of ‘counting the parts of the community’ against the exclusivity of the ‘consensus’. Politics, in other words, ‘counts the parts of those with no part’. If history is written by the victors, radical political movements are only as successful as their ability to ‘dissent’: to restructure social formations such that they include previously unheard voices. Only then can you see the wider picture; without it, you’re doomed to repeat the same mistakes.

This is, indeed, the central point of Harris’s article, just in reverse:

Getting history wrong will, in the long term, mean that lasting solutions will be sought in the wrong places. While the only effective strategies must come from Aboriginal people themselves, a final solution cannot exist outside a recognition of the true nature of the past treatment of Aboriginal people.

It’s seems obvious. But then here we are.

Historian Alyssa L. Trometter also describes the conflict of how to reconcile history to the present, specifically regarding the failure of ‘consensus’, or ‘police’ politics (to use Ranciére’s terms) to effect ‘renewal’ (to use Baldwin’s). In her thesis on the linkages between Malcolm X and the Aboriginal Black Power Movement, she explains how the 1967 referendum to remove clauses that ‘blatantly dicriminated against Aborigines’ won with a landslide 90.77% ‘Yes’ vote, yet failed to change the reality on the ground, In response to the unendurable living conditions of most Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders and the heel-dragging of the Australian public, Black Power movements started to grow, influenced by the ideas of, among others, Malcolm X.

Groups like the Redfern Black Power Caucus, led by activists Paul Coe, Gary Williams, and Gary Foley, cultivated ‘community service programs’ and alternative ‘police patrolling’, inspired by the Black Panther Party in the United States. ‘Armed with pens and paper’, these patrols recorded ‘unjust police behavior directed towards Aborigines’ and would then, with the assistance of lawyers, ‘provide free legal advice and representation to those unjustly accused’.

Small as these acts may seem on their own, they symbolize the attempt to document an alternative version of history. By thinking outside the prescribed modes of change, they were able to imagine a different possible future.

The fact is, the normal ways of counting a political body or affording and upholding their right to a higher standard of living, eventually fail, as they cease to interrogate the basic assumptions built into the lens that forms their vision. The losers are always already outside the picture’s frame, or just blurs in the background.

This seems to me to be the crux of Baldwin’s point. But it is the hope, too, offered by The Fire Next Time itself, as a work: often the one who has endured adversity ‘in order to save his life […] is forced to look beneath appearances, to take nothing for granted, to hear the meaning behind the words’.

Perhaps we are faced, collectively, with an opportunity to try and do this, and rather than further entrenching ourselves in the broken paradigms that our language has so far positioned us within, we might try to ‘hear the meaning behind the words’, and recognise that terms like ‘integration’ or ‘self-management’ risk meaning merely different orientations of the same thing. That is: the persistence in misunderstanding what it is we are indeed being ‘integrated’ into or, as the case may be, ‘released’ from.

In 1962, sat somewhere in New York City, Baldwin wrote that:

Now, there is simply no possibility of a real change in the Negro’s situation without the most radical and far-reaching changes in the American political and social structure. And it is clear that white Americans are not simply unwilling to effect these changes; they are, in the main, so slothful have they become, unable even to envision them.

That was then and this is ‘now’, and though the two countries are divided by an ocean, I’m inclined to say the question, if not the answer, probably remains the same. At 19, Dylan Voller is sat somewhere wondering what kind of life he’ll enter into, even in spite of the one he’s so far been subjected to. Mick Gooda is sat somewhere probably wondering how the hell he’s supposed to upheave a system so seemingly unwilling to look its past, let alone its present, in the face — after all was said and done, John Elferink, the NT’s former Attorney-General, still got a pat on the back, remember, with his former boss saying he should be "applauded" for efforts at reform that left young men stripped naked, punched out and hog-tied.

Any visions, whomever they arrive at, will no doubt come with their own blind spots and should be subject to continual (re)assessment. There’s never been an easy fix, and chimeras abound where there is struggle. But we should embrace the difficulty rather than shy away from it. After all, this is the power of Baldwin’s question, which was a simple one:

Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?

[1] “"I am called Baldwin because I was either sold by my African tribe or kidnapped out of it into the hands of a white Christian named Baldwin, who forced me to kneel at the foot of the cross. I am, then, both visibly and legally the descendant of slaves in a white, Protestant country, and this is what it means to be an American Negro ..." James Baldwin, ‘Down At The Cross’, The Fire Next Time, p.98. Dial Press, NYC, 1963.