Kick The Can: How International Street Art Took Dunedin By Force

Eloise Callister-Baker on Dunedin's street art spat

Public art is a strange beast. Often shackled to a bustling part of town, the beast is confronted by human eyes, children’s curious hands, sometimes spray cans, sometimes anarchic stickers. The art might cause uproar at first, but often this fades as it settles into its place.

That uproar isn’t a bad thing. Public art should take risks, push art and artists, and remain relevant enough that it becomes a significant fixture in a community.“I don’t think it is the function of art to be pleasing,” Richard Serra commented when his sculpture Tilted Arc (1981), which sliced across and obstructed the Federal Plaza in New York City, created public outrage. “Art is not democratic. It is not for the people.”

The controversy surrounding art, especially art made for public space, often centers on a story of imbalance – of a minority group invoking their powers to commission an artwork in a popular part of town and the public feeling unjustifiably ignored. Each time a work is commissioned, it raises questions about the international and the local, whether budgets were appropriately allocated, what is the best artistic practice when commissioning and creating public art.

At the bottom of the world, Dunedin has its own public art works that have raised eyebrows. The $45,000 that funded Regan Gentry’s molar sculptures, placed at the harbour mouth in 2010, was too large a price to pay for the manifestation of a visual pun for some. More recently, the focus has shifted to the abundance of funded street art and murals, now colouring-in parts of Dunedin, especially a semi-abandoned section of the city, just south of the Octagon, which is in the midst of gentrification.

In August, the University of Otago, partnering with its student association, spent approximately $17,500 to fly Fluke, a Canadian graffiti artist, from Montreal to Dunedin to make a street art piece on campus. Fluke’s skillful work, aided by his assistant, depicts two women engaged in a hongi – geometric flares of colour flowing from each greeter. The university and student association's endeavour had noble goals – to connect the campus to the wider community, encourage local and international artists, and continue the campus “beautification” project that began in 2013 with a work by New Zealander Sean Duffell.

But is this international, quick-fix commercial project how any of these goals should and can be achieved? Do local artists feel impassioned now? Are they really contemplating the Canadian’s work, preparing to extend on their own practices?

A non-profit group of volunteers, known as Dunedin Street Art (DSA), provided assistance with Fluke’s work, and have aided more than 25 public works in only a couple of years. The aerosol hongi acts as a connector piece between the university and the street art pieces creeping across the walls of Dunedin, especially south of the Octagon. The group quote Raymond Salvatore Harmon in BOMB: A Manifesto of Art Terrorism on their Facebook page. “Art is an evolutionary act. The shape of art and its role in society is constantly changing. At no point is art static. There are no rules.” Except, of course, when there are.

After an initial successful project where Belgian artist Roa painted a huge tuatara on a wall on Bath Street, the DSA began to search for more artists, consult building owners and the Dunedin City Council (who only has involvement in the resource consent process) and set up a funding initiative to assist artists in creating street art works. They also formulated a list of criteria for submissions so local and international artists could send in their own proposals for review. The DSA, it seems, stick as close to the rules as they can.

The size and speed of the project is impressive and has attracted a huge amount of attention – achieving a major goal for the group who aim to create a world renowned project. But it is these qualities that have led DSA to bulldozing over a few crucial issues.

With only eight out of the 25 locations on the street art map featuring New Zealand artists’ work, the ratio of New Zealand to international artist is significantly weighted towards the international. Only a handful of these works take local themes as their subjects. The ratio of female to male artists is also poor. One artist involved told me that the original list of artists for the project didn’t include locals or women – DSA responded to these issues once complaints were made, especially by artists, but the overall project is still lacking, even tokenistic, in its inclusion of both.

Whether supporting an abundance of international artists can be justified, even if it means local artists are missing out or brushed off as inferior in skill, is a difficult question. Maybe it shouldn’t be asked – or at least not framed as an issue where the local is played off against the international. This dichotomy is, after all, breaking down. Following his lecture on global art production and local meanings for Vancouver Art Gallery, Matthew Stadler wrote in an accompanying essay:

The debates that shape new commissions, as well as institutional commitments to home localities, can no longer rest on an ideali[s]ation of ‘the local’ nor a contrast of local needs to ‘global’ ones. Every locale is global. The institution and the city are at the centre of a connected, dynamic globe, always—never a remote or special space awaiting the arrival of art and insight from distant capitals, always the centre of a global discourse that returns and returns, as blood through a heart.

Stadler argues for shifting the discussion away from viewing commissioners of global art practices as maliciously cultivating power imbalances, to understanding commissioners as crafting imbalances to make new art possible. By linking the institution to the role of the dominant narrator, and the local to the idealised, passive receptacle to be explored by the outsider, Stadler deliberately flavours his main discussion with the language that traditionally surrounded Orientalism. But rather than see this relationship as negative, he emphasises the need for artists and institutions to start focusing their conversations on how “a purposefully organised imbalance of power can be used to enable divergent interests.”

While this is a useful way of viewing the relationship, does there need to be some limitation on this global way of thinking? What happens when a Canadian artist is given nearly $20,000 to contribute his voice and his work to a community he has no long term attachment to, while other important local artists constantly struggle to make ends meet - let alone have enough income to create work that pushes and engages the community from an internal and personal perspective?

This is more than a parochial NZ ‘bottom of the world’ preoccupation. It's also how some members of the local artistic community framed the discussion following the news of an $8 million Jeff Koons sculpture to be commissioned by the Sacramento Kings and given a permanent place outside the new Sacramento arena in California this year. Local artists were not even given the opportunity to present their own proposals, while the decision to approve the East Coast millionaire's work was made by a nine-member panel from the Sacramento Metropolitan Arts Commission.

But outsider/insider or international/local relationships don’t always create negative tensions. Artspace, in Auckland, is at the forefront in New Zealand when it comes to understanding and facilitating contemporary art practices, exhibition making, critical thinking, and artistic research at national and international levels. In pursuit of its goal of bridging the universal with the contextual, Artspace has developed a deep experience in how art and artists function in multiple spheres. This is reflected in the appointment of the internationally experienced Adnan Yildiz as its director last year. Yildiz studied in Istanbul, worked throughout Europe and was drawn to New Zealand because of the interesting things going on in art here.

When Artspace works with the international – whether it is an international artist, visiting curator or guest lecturer – they make sure the content is connected into the local in some way. “Whenever someone is invited from overseas to do a project here, there is serious thinking about what is going to be the relevance of this project in New Zealand,” Anna Gardner, the Gallery Administrative Manager, explains to me.

“That’s not necessarily about the project responding directly to the context here – sometimes we are just bringing in an existing work that hasn’t been seen in New Zealand – but it’s about asking: what is the New Zealand context going to do to that work? What is this work going to do for an audience here?”

Gardner directed my attention to their recent exhibition with Marysia Lewandowska as an example of their process. Lewandowska’s work addresses social housing and thoughts about what is common space and the role of capital and the commune in relation to common space.

“These are all bits of thinking that [Lewandowska] has formulated around her experiences in China, in the UK where she currently lives, and in Poland where she grew up. But I think, given the current conversations in Auckland about social housing developments and the housing crisis in general, this is a work that can get the public thinking about a topic that is important to people here, and she comes at it from a slightly different angle.”

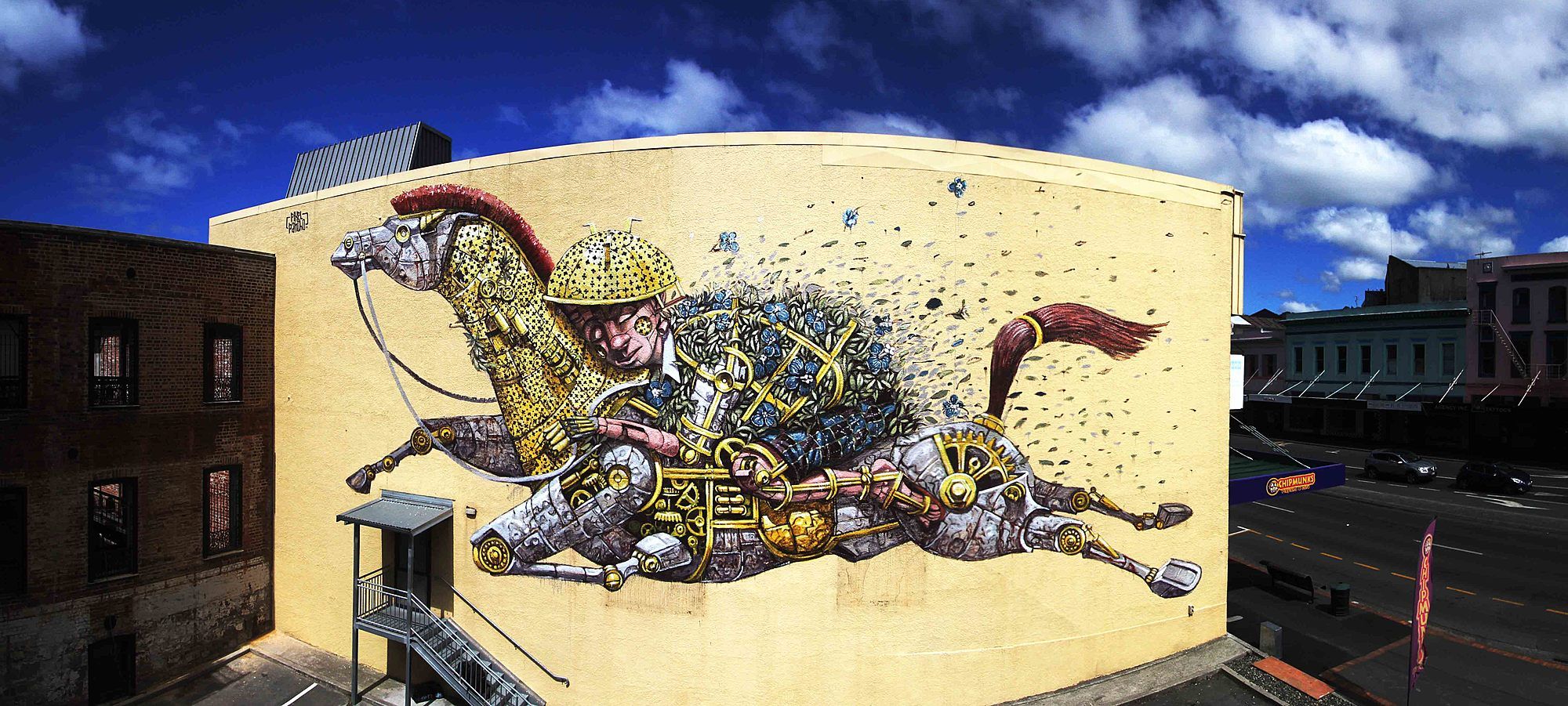

The practices of thorough research, risk-taking and relevance mean that Artspace consistently connects and challenges its audience. Whether the art facilitated by DSA and the group's own practices align with the practices of an experienced New Zealand institution like Artspace remains a lingering question. My own flat, located in the heart of Dunedin’s “warehouse precinct” just beyond the Octagon, is now enclosed by international artists’ works that were aided by the DSA. While some, like Italian artist Pixel Pancho’s giant boy riding a metal horse and Argentinian artist Hyuro's group of faceless protesters, are engaging and colour-in the cityscape without overbearing it, other additions lack in aesthetic and curatorial tact.

Natalia Rak’s Love is in the Air, which depicts a young girl kissing the cheek of a surprised thick-rimmed glasses wearing boy, was opposed by some residents of the building and has led to more mixed responses to the DSA’s project as a whole. “Our darling ‘DCC policy planner – heritage’ officer knows nothing about streetscape aesthetics, conservation of cultural heritage landscape – it shows and shows again,” commenter Elizabeth wrote on the What If? Dunedin blog. “He is in charge of decimating the look of buildings with, as I call them, vacuous tattoo examples of shit art. There are three example of murals that leap above this level which I applaud for the sites/surfaces involved. The rest is social media driven babble...”

Another work in the trail that simply features a young woman smiling was described by Dunedin writer Brendan John Philip in fortnightly street press Point as falling into the “street art trope of the contextless-female-portrait-produced-by-a-man and has to be called out for the bullshit it is.” Philip believes the artist’s “treatment of a woman as empty decoration is pretty much tantamount to just scrawling a big cock and balls on the wall.”

At what point does an ongoing public art project like this implode? ‘Art for the community’ reigns with a power that exceeds its modest egalitarian origins – once there, it cannot be avoided. It's an access point into “art” for everyone, including those who never actively seek out art in galleries or otherwise. But commissioning a public art piece goes beyond practical details like gaining consent from a building owner and the issues of long term maintenance. Careful curation and a deep consideration of how the piece may take risks, push art practices and understanding, and whether the work represents a time or has a quality of timelessness are necessities. These are, after all, projects that go beyond you or me. They endure.

A recent local example of 'public art' done with the consideration and process Gardner discusses is Deanna Dowling’s In search of of gold, the stone was there all along, created for a Blue Oyster Art Project Space exhibition A Tragic Delusion. Dowling’s work features two cracks in the ground in different parts of the city that are filled in with either Oamaru stone or Oamaru stone and gold. The work directly links to foundational materials used in building some of the key remaining heritage buildings in Dunedin.

If an institution or group are commissioning an international artist, Gardner’s description of how Artspace works with the international should be applied to the public art context. For Artspace, if the travelling artist is actually producing work in or for the New Zealand context, the gallery make sure to aid them with information and research beforehand and allow adaptations for the project that respond to what’s going on here once the artist arrives. Artspace make sure international artists, curators, speakers become closely connected with the art community here, not just through big public events but also through studio visits and dinner invitations to meet like-minded individuals.

And ultimately, if we believe the public should have an opportunity to consult on motorways, high-rises, and housing selloffs, is art that changes where they live really exempt? Another option for public art practices could be to follow in New York City councilman Jimmy Van Bramer’s footsteps. Bramer introduced a bill this year that aims to enhance the Percent for Art programme (that allots one percent of the budget for all city-funded construction projects for public art) by legally mandating public hearings or community board meetings where residents can also give feedback on the proposed art work. Plans of a $515,000 bright pink, seemingly melted sunbather sculpture by Ohad Meromi inspired this bill, when members of the public took alarm at its size and colour scheme.

As a group of enthusiastic community volunteers, the DSA cannot be expected to suddenly have the institutional know-how and experience that are central to the operations of galleries like Artspace. But anyone behind a public art project, which is what the DSA trail has become, aspires to a certain cultural role and has to meet its obligations. Whatever is happening in discussions between DSA members, the project needs a serious dose of criticality. If the plan is to breathe life into Dunedin, especially in the warehouse precinct where renovation, new projects and business ventures seem to be appearing weekly – more and more people will begin to experience the funded street art works on a daily basis. A stronger and more representative curatorial eye is crucial, as well as consultation with art practitioners, experts and the public. Public art will always remain a strange beast, but having unleashed it south of the Octagon, DSA now need to train it out of its bad habits.

Cover Image: Pixel Pancho (ITA)'s mural by Princes Street. Courtesy of Dunedin City Council