Internet histories | 23 December

The cult of gentrification, questioning same-sex marriage, chasing R Kelly, Shia LaBoeuf's pathological plagiarism, and uploading everything.

This fortnight:

The cult of gentrification | questioning same-sex marriage

chasing R Kelly | upload everything

Shia LaBoeuf's pathological plagiarism

Matt

Digitising everything is kind of this thing that museums and libraries have recently decided they need to do – to increase public accessibility, sure, but also to reduce risk and often the amount of real estate they need. The Smithsonian, for example, has embarked on an ambitious project of 3d-scanning important exhibits, allowing people to print them at home, should they have the technology. More recently, the National Library of Norway has announced it’s going to digitally scan all of its literature since forever until now and offer it publically to Norwegians as a free download.

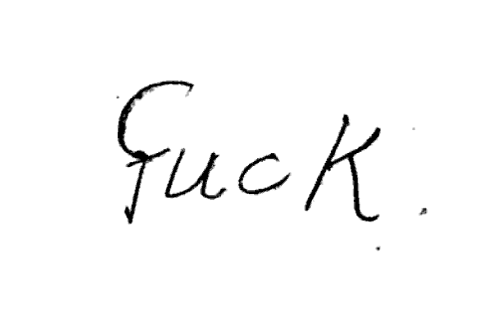

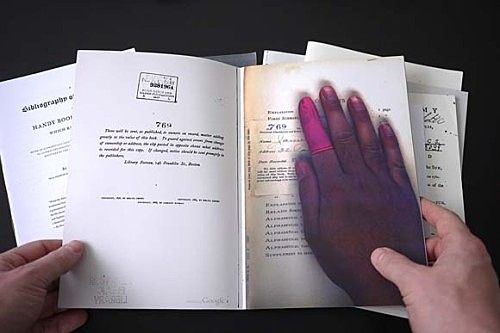

It’s the kind of mind-bending, singularly progressive move that’s simultaneously unthinkable and astute – especially amid the context of Google’s US book publishing issues (recently resolved, admittedly). The scale of the project shouldn’t be underestimated; hundreds of thousands of books mean many millions of pages, each needing to be turned and scanned and itemised… but perhaps not scrutinised. An amazing tumblr is dedicated to recording the human and machine errors of digital transcription, and they range from the arcane to the eerie to the hilarious:

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Severe distortion. Throughout Oratio de Gloriosa Tornaci Expugnatione by Georg Christoph Model (1719). Original from the Bavarian State Library. Digitized February 9, 2011.[/caption]

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Page torn, perhaps by Google Books employee. The photograph of p. 651 is of a whole page, but after the leaf is turned, there is a tear in the photograph of p. 652. From Early Days in Detroit by Friend Palmer (1906). Original from the New York Public Library. Digitized February 7, 2008.[/caption]

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Handwritten profanity. From the front matter of The Mummy!: A Tale of the Twenty-second Century, v.1, by Jane Loudon (1828). Original from Harvard University. Digitized March 1, 2006.[/caption]

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="500"] oops[/caption]

But it’s not all chapters and checksums. Jocelyn Small, writing (in the early 90s) on ancient Greek filing systems, notes improved organisation tends to have a major consequence – one that’s often barely anticipated:

What is perhaps most interesting here is that each tool or technology makes it possible to deal more efficiently with the current accumulation of words, but by virtue of its success propagates yet more works that need yet more techniques to control them.

At the time she was writing, the Dewey decimal system must have felt barely capable of categorising burgeoning banks of CD-ROMs, and sometimes it seems like even mighty Google, which uses over 200 sorting algorithms to deliver results to your browser in <0.1s, is fighting a losing battle. Especially when we’re uploading 35 petabytes of new data each month (if there were an .mp3 that size, it would play for 70,000 years), and especially when it’s impossible to find that specific hilarious doge meme you saw somewhere last week. Case in point: the British Library has released several million digital scans of books from the 17th-19th centuries, but they've done this via Flickr for some reason, and included almost no metadata, so it's a bit like getting sprayed in the face with a whole lot of vaguely racist woodcuts. But I guess it's better than nothing?

Anyway, this question of how we organise our cultural record isn’t going anywhere quickly, Ultra Fast Broadband network notwithstanding. At stake is the way we remember ourselves, and whether or not we’re simply producing digital palimpsests that foster entropy even as they’re supposed to cohere.

Bronwyn

It’s hard to know if Jim DeRogatis* is a man possessed, or just someone who won’t give up on the biggest story of his career. Earlier this year, prompted by R Kelly headlining the Pitchfork festival, he recorded a series of conversations with a range of academics, critics, and R Kelly fans, mostly around the question of “Why, (would you book as a headliner a man known to have acted on his disturbing attraction to teenagers) Pitchfork?”.

While there’s a slight tendency to paint DeRogatis as a bit of a lone wolf, there’s always been plenty of other people writing about Kelly. The difference with him is his complete involvement with the case: sent the original tape of Kelly having sex with a very young-looking female, he was part of a team that interviewed many people that were involved, and he was called to testify at Kelly’s trial for child pornography (but refused, citing protection of his sources).

Last week, Jessica Hopper, a contributor to Village Voice and former critic of DeRogatis, published an interview with him, and uploaded scans of his original articles from the Chicago Sun-Times, which are otherwise unavailable online. It would be fair to say this interview has hit the sweet spot of timing and the right platform; Hopper has said that if she knew it would be so popular, she would have included even more of the original damming material.

Hopper is interested in why Kelly is still so lauded, why he can still get away with being so explicit about what he wants (pussy) and how he wants it (young).

To DeRogatis, there’s multiple reasons for this. Part of it is the gap between (some) music critics and journalists:

A lot of people who are critics are fans and don't come with any academic background, with any journalistic background, research background... Part of what we do is journalistic. Get the names right, get the dates right, get the facts right.

There’s also the fact that of who Kelly’s victims were:

The saddest fact I've learned is: Nobody matters less to our society than young black women. Nobody... All of them settled. They settled because they felt they could get no justice whatsoever. They didn't have a chance.

And our terrible, unshakeable attachment to the ironic, to the liking of things not despite them being terrible, but because they are, and how that irony gives them a pass. Once something has passed over to the land of camp, of kitsch, it’s not held accountable to the same standards anymore:

This deeply troubles me: There's a very -- I don't know what the percentage is -- some percentage of fans are liking Kelly's music because they know.

* Mr. DeRogatis is also the recipient of a famously irritated voice mail message from Ryan Adams (“Fuck you man... you obviously have a problem with me...You’re obviously one of these people that comes to gigs and bums people out, standing around with your notebook.”)

Kyle

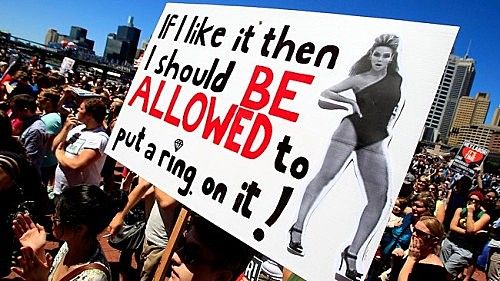

The wave of victories of the same-sex marriage movement across the globe in the past two years has been framed by many as eliminating one of the last remaining prejudices tolerable in society. Overt racism and sexism are now fauxs pas, and it seems as though homophobia will follow suit.

Of course, homophobia, like racism and sexism, won’t be solved by increasing access to marriage. Homophobia is engrained in our social and cultural practices, in our media, politics and education. Progressives might celebrate same-sex marriage as gaining ground towards ending homophobia while still recognising there is more work to be done.

In a recent article, Dean Spade and Craig Willse criticise the view that the same-sex marriage movement is “progressive” or “leftist” at all. Marriage has always been an exclusionary institution which reifies certain types of relationship, they argue. It adapts when necessary for its own survival, by slightly altering the boundaries of correct love, but still contributes to defining certain types of sexuality as “bad’: non-monogamous, queer, intersex, and non-procreative sexualities are all various degrees of taboo. It remains an institution obsessed with icons of virginity, gender roles, and property rights. It is an institution that remembers its use to police racial boundaries and to demolish indigenous communal landholdings. How can queer leftists support it?

A similar line of gay “victories” occurred in the campaign for the repeal of the US’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” law, which prohibited openly gay men and women from serving in the US Armed Forces. The march against homophobia became conflated expand the scope of militarism and romanticising violent military service. We are not immune from this in the antipodes; recently, the New Zealand Defence Force posted an “It Gets Better” video, which nominally left-wing groups such as GayNZ lauded.

Spade and Wilse summarise their surprise as those who have been engaged in queer activism for decades:

Perhaps if the same-sex marriage advocacy story is good for anything, it’s as a great illustration of the power of philanthropy to shape a movement. We have seen what some say started at street rebellions against police violence at the Stonewall Inn and Compton’s Cafeteria turn into advocacy for prosecution and partnership with police. We have seen a movement birthed during and because of the radical politics of anti-war and decolonization resistance of the 1960’s and 70’s become focused on the right to serve in the US military. And we have seen the eclipse of queer, feminist, anti-racist and decolonial critiques of government regulation of sexuality and family norms evolve into a demand to get married under the law. It is stunning to watch, in such a short period, the rebranding of institutions of state violence as sites of freedom and equality.

Amending social and state structures to address skin-deep inequalities is important. Homophobia, like other forms of bigotry, should be excised from our lives. But it’s critical that we look to the core of structures that we are trying to reform and see whether they are suited to the kind of society we want to live in. It may be that social justice can be best served by dismantling them altogether.

James

You know the cycle: cheap rents in a dingy area of town, artists and musicians move in, galleries and bars open up, then boutiques and cafes - next young couples choose to live there, soon becoming young families. The focus goes from the percentage alcohol to percentage interest rates. Suburbs can go from being rough and risky to highly desirable within a generation. This isn’t a polemic about our obsession with the endless march of property prices, but about the limits of gentrification.

David Madden is highly critical of the Cult of Gentrification in this piece for the Guardian:

After gentrification takes hold, neighborhoods are commended for having "bounced back" from poverty, ignoring the fact that poverty has usually only been bounced elsewhere. In an insidious way, the narrative of "urban renaissance" – the tale of heroic elites redeeming a city that had been lost to the dangerous classes – permeates a lot of contemporary thinking about cities, despite being a condescending and often racist fantasy.

While his criticism is aimed at London or New York, and could apply to Auckland, it’s worth thinking about in the context of the Christchurch rebuild. Gentrification is alive and well in the suburbs of Christchurch, but what will happen in the (former) CBD? How do you gentrify a gravel pit?

Madden’s thesis is that through “rejuvenation” and “renewal”, an undesirable area can be transformed into a desired one. The process and it’s outcome must be viewed through a neo-liberal prism; the ultimate goal of gentrification isn’t a better city or a nicer area, but increased property prices. Artists, musicians and other creatives are a key players - willing or unwilling - in this transformation. Their expression gives the area some sense of a new identity, one that makes a break from it’s previous, poor roots.

The earthquakes halted the gentrification of the Christchurch CBD instantly. The trendier, edgier ares - High St, Poplar Lanes - were made up of buildings that had cheap rent, but lacked the structural integrity to withstand extreme seismic forces. So where to for the struggling artists of the flat city? The economic realities of the rebuild will prevent all but the most established players from returning to the city. I can’t think of a major Western city that doesn’t have art intrinsically linked to it’s core - but maybe we’re about to see what that looks like.

Joe

In terms of actually going to the movies, I haven't really noticed Shia LaBoeuf before now - acting-wise he just has to gawp convincingly on a blue-screen in the Transformers films, while the oddly straitened 70s classicism of The Company You Keep kept a hard-headed journalist nerd role that was his to dominate under wraps while a bunch of veterans did a big chorus line reunion. He's garnered a lot more attention for being a incongruously troubled famous dude, pulling knives, crashing utes, and now, a brazen act of plagiarism that actually fascinates me.

Plenty of people, myself included, are plenty unoriginal in their creative pursuits - paralysed by influence, desperate to impress, but they'll tend to go for an overfamiliar pastiche and tend to get over the line on confidence, if anything. We've learned that LaBeouf plundered a 2007 Daniel Clowes comic for his reasonably acclaimed short film HowardCantour.com - not just the skeleton of the plot, but direct passages of speech, and shot-for-shot recreations of certain panels. Then he apologised, but even that appears to have lifted from a handy paragraph or two on Yahoo Answers - with more falling out every time you give his online presence a shake.

A number of worthy publications (er, on the Internet) have taken it upon themselves to patiently explain to LaBoeuf why plagiarism is terrible in patented open-letter style, but this ignores how pathological his actions seem to be. You can probably get away with such a direct steal in your first year of film school, assuming you're not a celebrity and you don't put it on Vimeo afterward. But LaBoeuf getting caught out - repetedly - was such a matter of when, not if! Is it performance art? Is he an incorrigible mimic? Is he experiencing the same anxiety we all do, but with an overwhelming phobia of the blank canvas?

The best analogous case I've seen is covered here in the New Yorker by the (incred) Ann Widdicombe: her broad and sympathetic overview of the literary crimes of Quentin Rowan (aka Q.R Markham), whose Ludlum/Fleming/McCarry-derived spy potboiler Assassin Of Secrets was found out to be an exhaustive and exhausting work of unattributed magpie precision: "plagiarism's Piltdown Man". And Rowan, who had little to gain and everything to lose as attention and acclaim loomed, couldn't help himself:

In the living room, he pointed out where a large table used to be. “That’s where I would write,” he said, and laughed, self-consciously. “ ’Cause I could spread out all the books and just . . .”

Rowan has been attending A.A. meetings every week for fifteen years, and he says that he tried to apply the program’s first step to plagiarism: “to admit I was powerless over it and it was making my life unmanageable.” In the end, though, he told me, “without constant vigil, it just kind of came back.”

Like an ex-addict, Widdicombe leaves Rowan trying to piece his life together - clean habits, healthy routines, a little original prose, day by day. So much of what drove him was a fear of his own inability, a gnawing, awful hollowness even though being a writer was what he'd designated himself to do. And I can imagine LaBoeuf, the successful blockbuster actor without a masterpiece to his own name, the reader of lines, the very talented shadow who lay awake and wondered if he was attached to a person at all, feeling the same shame. It's humiliating, but I can't understand why we're lecturing him.