A Journey Down The Banana Supply Chain

Edward Miller on the price - and journey - of bananas

From my Wellington apartment it’s a ten minute walk to my local supermarket, where I can buy an 850g bag of bananas for $2.99. Ten minutes later I can be home and flipping the skins off those bad boys before they even knew what hit them.

Ten minutes after that, they’re in fat little slices and I’m mixing a batter of half a cup of flour, a quarter of a cup of sugar, a quarter of a cup of water and two eggs. I’m making maruya, Filipino style banana fritters as an afternoon snack, because I can. It’s basically a cooked banana, wrapped in a Edmonds Cookbook-style pikelet and fried until crunchy.

Filipinos normally use saba bananas, a smaller and slightly blander variety than the standard Cavendish I’ve got. The Cavendish monoculture began to achieve prominence 70 years ago when the famed Gros Michel succumbed to blight; today, they account for 45% of the world’s banana crop.

It’s pretty straightforward. You dip your banana slices into the batter, then deep fry them in some hot oil. Dry them off with a paper towel and throw a bit of icing sugar or white sugar over them. They’re delicious (especially if you’ve got some chocolate sauce or Nutella), though I can’t vouch for whether they’re necessarily nutritious (especially if you’ve got some chocolate sauce or Nutella).

They’re also really easy to make, and I can make it even easier for myself if I get my bananas delivered to my doorstep (although my online retailer slaps a comparatively steep delivery fee on them). But easy is subjective, particularly from this end of the supply chain. I give some dude $2.99, I get 850 g of bananas; sounds like a fair trade, right?

Suppose I follow my $2.99; where do I end up? Bananas are the world’s most-consumed fruit crop, and New Zealanders really love them - at 18kg each a year we eat about as many bananas as anyone does anywhere. That means we’re each spending about $63.00 a year on bananas, or around $300 per household. At that price if you live until you’re 80 and eat your 18kg a year, you’ll consume $5000 worth of bananas. Fair enough you say, bananas are delicious; but who gets that $5000?

For a start, around 80% of the price I pay for those bananas won’t reach their country of origin; it goes back to the shareholders of the supermarkets and the other big players in the banana game, and from there, like so many decimal points, it makes its way to wherever they choose to reinvest or spend it. That world – money poured into Californian nutrition foundations, the pioneering world of wearable fruit, bizarre imperial endeavours, even filmmaking – I can only glimpse from my vantage.

Last year, however, I was lucky enough to follow the remaining fifth of my banana dollars. Those 60 cents take me into the far reaches of the Pacific. They bring back memories of elation and chafing, bumpy rides through plantation roads that criss-crossing breathless valleys, and the mottled scars of old exit wounds. Even through the maruya batter and the icing sugar (which tell their own stories), the bananas taste like its constituent parts: fertile tropical soils, complex carbohydrate and rich sugar, doused in toxic chemicals with a hearty dose of human labour.

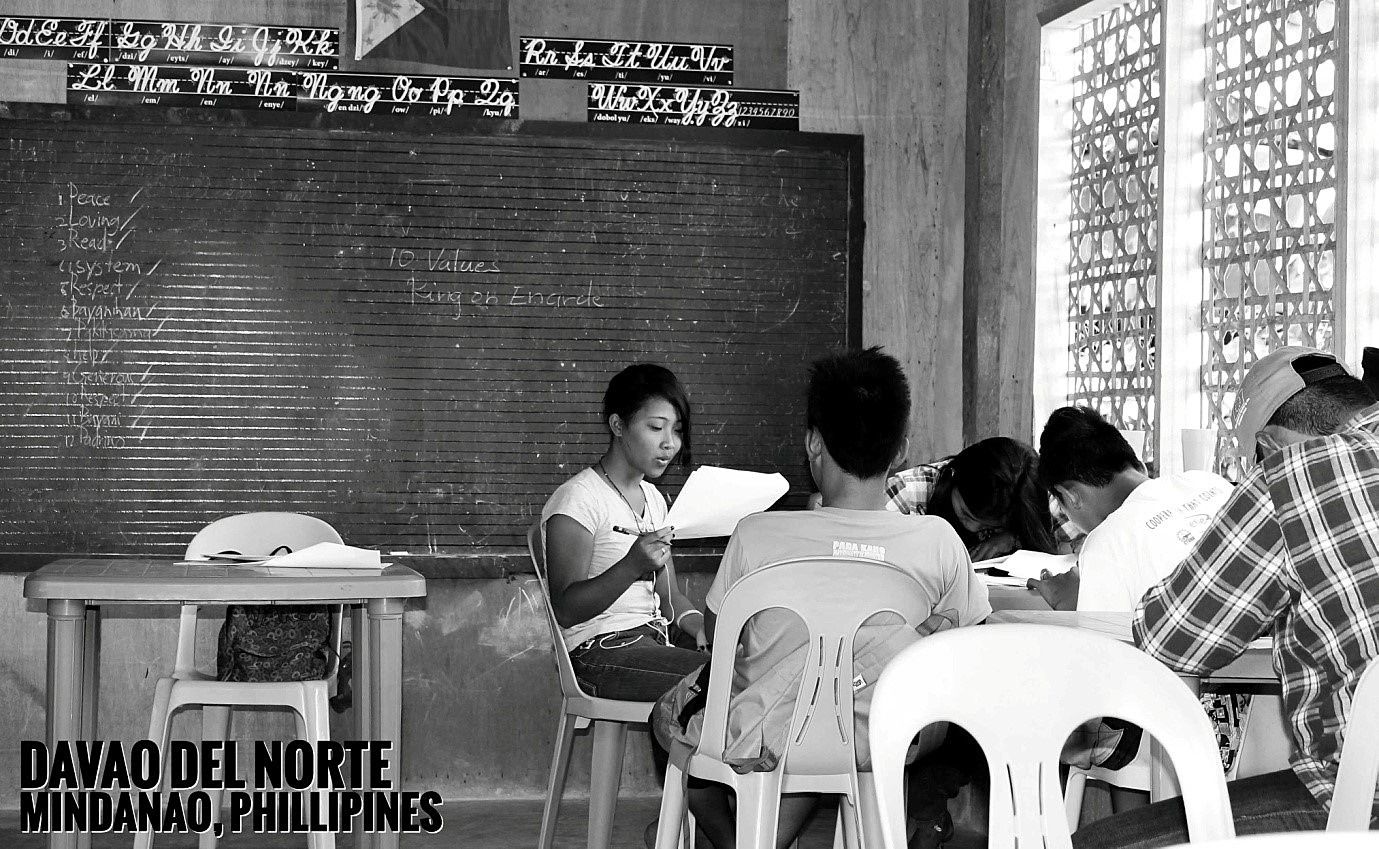

Davao del Norte; 07°21′N 125°42′E; October, 2014

Rewind nine months, and the scorching mid-30s Celsius heat has got me roasting something chronic. I’m sitting in a concrete cube-cum-classroom in Davao del Norte (a province on Mindanao, the Philippines’ southernmost island) taking a lesson from Marco Castillo, General Secretary of the Lower-Siocon Plantation Labourers Union. His hands are a patchwork of calluses, and he laughs as he explains his situation. The union organiser, Bong, listens closely but says little.

Marco’s interested in hearing what I pay for my haul in New Zealand, and I recite the above statistics about NZ banana consumption. From the classroom window, it’s banana plantations as far as you can see: Davao del Norte province alone has 35,000 hectares of them. To the north, Compostela Valley has 22,000 hectares; to the west, North Cotabato has a further 15,000.

These bananas are produced for markets in Japan, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, China, and New Zealand. Accounting for 93% of all Asian banana exports, the Philippines’ is now the second largest banana producer in the world, and the Philippine government is bullish about the industry and its future prospects.

Why? Because the banana industry – and the banana republic with it – is rapidly transforming. Whereas in 2002 five multinationals alone controlled 70% of the global banana import market, their share has now shrunk to 44%. Those same multinationals are quickly pulling out of the production end of things as well. Gone are the days of the vertically integrated Third World plantation; yesterday’s banana moguls pale in comparison to the reach of today’s global supermarket empires.

In their drive for cheap consumer prices, banana multinationals are pulling up their roots, selling the hacienda and becoming logistical players, sub-contracting work to smaller operators to push the squeeze further down the supply chains. These days those operators are called ‘institutional buyers’, and are fast becoming the handmaidens of the supermarket-industrial complex.

Even Chiquita, the company Gabriel Garcia Marquez once said had “changed the patterns of the rains, accelerated the cycle of harvest and moved the river”, is not immune to the decline of banana imperialism. They used to control the fate of nations: it was their complaint to the US government about Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz’s land reform agenda that lead to the CIA’s involvement in a 1954 coup d’état, and some claim their complicity in the 2009 coup in Honduras. Last year, however, Chiquita was purchased by a Brazilian orange-juice maker (Grupo Cutrale) and its investment firm partner (Safra Group) for a lousy billion NZ dollars.

Banana-producing nations now vie for supermarket shelf-space. Western consumption patterns shape how developing countries actively compete with one another to hollow out investment and labour laws, to expand production to squeeze profit as much as possible. For this reason, Marco tells me, he doesn’t get paid the Philippine minimum wage.

The Philippines’ complex sectoral and regional minimum wage system means that agricultural workers in this part of Mindanao workers shouldn’t be paid less than 302 pesos a day ($8.82 a day). However, Marco explains to me, because of something he calls the “Bambi law” he doesn’t even get that. The Barangay Micro Business Enterprise Act 2002 – the BMBE (pronounced ‘bambi’) law – means that if your business has assets (including loans) worth less than three million pesos, then you don’t have to pay your workers the minimum wage anymore, and a variety of other tax benefits to boot.

The law was designed to foster innovation and entrepreneurship by encouraging the formation and growth of small enterprises. But, Marco explains, it’s the multinational buyers and the supermarkets that benefit from this wage repression.

At the end of a day’s harvest, an institutional buyer buys the bananas that he’s gathered - but Marco doesn’t work for the buyer. The buyer is technically purchasing the bananas from a company with a holding of vast plantations - but Marco doesn’t work for that company either.

That’s because the company that owns the plantation that surrounds us contracts out the harvesting of the land to eight entrepreneurs, whose companies each have a market capitalisation of less than three million pesos. One of those entrepreneurs is Marco’s boss, using the Bambi law to lawfully escape other obligations, as the financial benefit of that law rises up the supply chain.

Marco is married and has three children to feed off his salary. He works out in the plantation, hooking bunches of bananas onto the raised rails that criss-cross its fields. The bananas are then washed and packed into boxes (each holding 13.5 kg worth) before heading off to the nearby ports where they will be exported.

The institutional buyer buys the packed boxes of bananas for 250 pesos ($7.18). In other words, they’re buying my 850g bag of bananas for around 45 cents a pop. “The workers are the milking cow of the capitalist,” Bong chimes in, inadvertently providing an apt comparison for a Kiwi to understand.

Marco also explains to me that although the landowner does not yet know there is a union on the plantation, he has managed to persuade about 90 percent of the workers to join anyway. Sitting in the shelter of the school room, one of the biggest reasons to join up is suddenly self-evident - the union has worked with community organisations to establish that school. It costs 25 pesos per child each way for workers to get their kids to the closest school in the nearby Barangay (community). That’s practically impossible on the parents’ salaries, but their schooling is free here. By night, it’s an organising room for workers.

As the swollen raindrops of the afternoon’s first monsoon rains dump down, lightning rods split the sky above the plantations. Henry and Marco tell me about the damage caused by Typhoon Pablo in 2012, explaining they’d never seen a typhoon like it before. The storm flattened about 10,000 ha of plantations in Davao del Norte and Compostela Valley, devastating both workers and small producers alike. In the aftermath, government-owned Landbank offered aid by way of loans to those small and medium farmers who secured a contract of at least 15 years’ duration with a multinational company.

Soon we’re on our way again, cutting across hills to our next destination in Compostela Valley. A truck up ahead carries armed police and heavy military hardware. My guide Danny tells me they are looking for the New Peoples’ Army – Maoist revolutionaries living deep in the mountains. Here, the operations of state and capital meld together.

Compostela Valley, 07°36′N 125°57′E, October 2014

Trade union secretary Jerome Arago is asking me what I think of the Court of Appeal’s decision. The sun has gone down, and we’re sitting in the shop that he owns just next to the banana packing house. Workers come here on their breaks to relax and recharge, and eat meals prepared by Jerome’s wife.

It’s a simple concrete building, the shelves adorned with sachets of 3-in-1 instant coffee and packs of graham crackers. The sound of chickens, pigs and giggling workers on break fill the night air, and the sweet coconut wine relaxes. When the resting workers hear I’m from New Zealand, they excitedly tell me that they’ve just packed 500 boxes destined for its ports – enough to keep 375 New Zealanders’ banana habits in check for a year.

The question that the court is deciding is whether there is an employment relationship between the workers from the packing house and the employer that owns the place. Such a relationship must be established for the workers to negotiate a collective agreement with better terms and conditions, and take legal action against the employer.

Like the High Court decision before it, and the District Court decision before that, the Court of Appeal is adamant in finding that an employment relationship exists. For this reason, the company – the subsidiary of a smaller institutional buyer - has appealed to the Supreme Court, which will take another few years. Jerome is suspicious the company will simply bribe the judiciary.

Jerome has good reason to believe the company is willing to bend the rules. The next morning, he shows me two scars – one on his belly and another on his bicep. You might not think they were bullet holes unless you’re told, since they’ve just nicked the skin on an angle. It was the first time Jerome had been shot, but not the first time he’d been shot at.

He was taken to a hospital in Davao City and then hidden for three months before returning. His friend, who was driving the motorcycle that he and Jerome were on at the time, was not so lucky. The assailant was never found, but Jerome believes they were paid by his employer.

Repression of trade unionists and other activists is all too common in the Philippines. The Philippine human rights organisation Karapatan documented the killing of 1206 activists during the Presidency of Gloria Arroyo (2001-2010), including union members, farmers and members of faith groups. The Philippines’ workers rights record scores a five on the International Trade Union Confederation Global Rights Index’s one-to-five scale, meaning “workers effectively have no rights” and “are exposed to autocratic regimes and unfair and abusive practices.”

Today at the packing house, there was a new issue. A number of workers had collapsed after inhaling a new preservative being applied for the bananas bound for the Chinese market. Those affected were rushed to a company doctor, who said they were simply dehydrated. Jerome tells me that they are trying to get information, but will not raise any dispute until they have some more evidence. This kind of occupational poisoning is routine, indoors or outside. Plantation workers are regularly doused in pesticides and fertilisers from the small planes that hang in the hot, still air over Compostela Valley.

It’s not like the institutional buyers don’t know about these conditions. A 2013 Oxfam-published report written by the Center for Trade Union and Human Rights into conditions in Philippines banana plantations revealed the use of underage labourers, working 12 hours a day, and often paid below the minimum wage, just like Marco. After the report came out Dole were forced to ditch the ‘Ethical Choice‘ stickers that had adorned their bananas.

Later that afternoon I visit another banana plantation operated by the same institutional buyer. I meet Arturio, a pot-bellied line worker tugging bunches of bananas fifty-a-time along the rails that lead to the packing house. He’s wearing a mesh beret and has a plastic diamante stuck to his front tooth, like some bizarre form of agrarian bling. I ask Arturio what New Zealanders could do to help him and his fellow workers.

“Eat more bananas.”

Wellington; 36°87’S, 174°78’E; June 2015

So I haven’t stopped eating bananas, and I haven’t stopped making banana fritters.

Increasingly, when I visit my supermarket, there’s a marginally more expensive group of bananas wrapped in tape and emblazoned with ‘Fair Trade’ slogans. The fair trade banana market is expanding quickly in New Zealand - yet for many consumers, it remains simply unaffordable. The very term can be considered a market access tool to some of the planet’s wealthiest consumers.

It’s good that we’re thinking more about our food, and fair trade consumers do provide significant incomes gains for some of the world’s poorest food producers. But it doesn’t solve Arturio’s problems today, and possibly never will.

For them a different strategy is required. I don’t know exactly what that strategy is, but I think it has something to do with assisting the on-the-ground organising work of their union, while confronting the inequality that lubricates our supply chains and acknowledging the blood that’s spilled to uphold those relationships.

This trip would not have been possible without the work of the independent labour centre Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU) and the Mindanao Interfaith Services Foundation. All names and brand names associated with this supply chain have been changed to ensure the protection of the workers involved.