Learning to Talk about Art

Ahead of Artweek Auckland, organiser Amy Stewart talks about how she faced her trepidation, got her shit together, and figured out how to put her thoughts about art down on the page.

Artweek Auckland returns this weekend, and runs from the 12th to the 21st of October (okay, more than a week - but a little creative latitude is pretty much a given in this territory). It sets out with a more ambitious goal than 'we'll put a lot of art somewhere, and sell tickets, and maybe someone will buy some of the art' - the stated object is to expand the visual arts audience through discovery and discussion. That's an ambitious and a terrifying goal, by the way - because making a fresh audience go and decide go see some paintings, sculpture or installation when they usually don't is one thing in itself, but asking them to talk about what it makes them think and feel is another proposition entirely.

Amy Stewart has worked as an academic writing and art history tutor, and writes for several art galleries. Her Masters degree from the University of Auckland focused on the aesthetic of memorial and post-trauma art, and she spearheaded a writing programme for Auckland Art Week back in 2012. She's back to try her hand this year - but, being curious about how (and why) someone would try to put text down on a page about what wordlessly looms before them, we've invited her to talk about her experience of learning to write about art (+ where it goes wrong, ++ why it doesn't have to).

I got into writing about art because I wasn’t very good at writing about anything else. Though I think the real problem was that I wasn’t very good at thinking about anything else.

I studied what my older sister studied at university (English and Spanish literature), but I never quite fully understood Joyce as she did, or Beckett as she did (though of course I did my darndest to make it sound like I did). It turns out that people who know you well are very good at knowing you well, and so I never got away with it. I went to art galleries when I was on holiday, but I went in the same way that I went to churches or battle sites. Places of interest. I never read art reviews because I, like a whole lot of people, thought that art was not mine.

I had never found something that made my jaw drop and my fists clench and in some cases my eyes water except music. When I would hear a song or an album that was stunning, I would usually come out with something deeply underwhelming to describe it to the people I was with: ‘that bit – that bit was awesome.’ We would all nod – yes, we knew it was awesome, we all understood it and felt it, but we couldn’t explain it to each other yet. As we listened more and learn to talk more, we developed a vocabulary to talk about music. This vocabulary wasn’t specialised, there was no jargon, but we began to be able to talk about the sound sequences we were hearing and reacting to so strongly to in words. By being able to talk about what we were hearing, we were able to access parts of these new sounds that we had missed, and our experience was deeper and better for it.

Fast forward to university and my modern art course. A sort-of friend first introduced me to Mark Rothko’s work in community college, and I will always owe him that. I decided to study art history (a decision I made after writing my first art history essay, on Rothko, Reinhardt & Cage, if you’d like to know) because I reacted to the paintings I was seeing in a way that I couldn’t easily put in to words. BUT – and this is the key – I really, really wanted to be able to. I wanted to talk about art because I was excited about art, and when you are excited about things, sitting in your room mouthing ‘that’s so awesome’ to yourself just doesn’t cut it.

People are articulate in different ways. I cannot draw and I cannot make music, for example, but that doesn’t mean that I can’t enjoy when those beautiful non-verbal sounds and images are presented to me (and I’ve always been a good talker). The artists who I work with, for the most part, feel deeply uncomfortable with words. Words dominate our world the way English is seen to dominate our world, suppressing a whole lot of ideas and sensations that can’t be expressed in it. Non-verbal arts take a back seat and are deemed secondary because, a lot of the time, they are harder to ‘get’. This breeds a sort of mistrust of the domineering power of the written and spoken word, which is a shame, but it is a reputation that is not entirely unearned.

I come from a family of lawyers and my boyfriend is a lawyer, too. I used to take great joy in pointing out when the lawyers in my life would resort to language that I didn’t understand. I would taunt them by saying they were being obtuse, exclusionary and elitist, but really I was just embarrassed at my lack of vocabulary and understanding. You will have spotted the flaw in my initial objection as well, namely that my discipline of choice – art – is also highly exclusive in this same way.

There is even, I shit you not, a thing called ‘International Art English’. Artist David Levine and critic/scholar Alix Rule explain: ‘This language has everything to do with English, but it is emphatically not English." It is born of language that is actually useful to describe art, but has spiralled out into this weird, farcical rubbish that does more harm than good.

Rule and Levine go on: “IAE rebukes English for its lack of nouns: Visual becomes visuality, global becomes globality, potential becomes potentiality, experience becomes … experiencability.” In short, like most other jargon, what could be used sparingly and effectively, is, intentionally or not, made ridiculous. Saddest of all, it makes us forget that you can actually use words to communicate with each other about art, instead of always needing to have some jargonistic ace up your sleeve.

When I see an artwork that I really love, I feel like my brain is going to explode. On one occasion, I just burst into tears*.It hums and vibrates and kicks at the sides of my head, and what is processed, and later printed out via a Word document like some ACME machine in a Looney Tunes cartoon, is a much more legible reaction. Because that’s what writing about non-verbal things is. You can distil reactions, you can point people in the right direction, and you can give them information that they need to get further into the piece, but you can’t make them enjoy it, and you certainly can’t make them write about it. Horses and water, etc. The ability to verbalise, though, is not just for essay writing (although I feel a lot of university students in particular would benefit from learning that essay writing is not some strange, pointless torture), but also as an incredibly useful tool that actually helps you think and helps you clarify those thoughts.

A lot of my writing comes from a place of fear, because I need that fear to help me work. I need that fear because a lot of the time the artists that I work with are also scared; we are genuinely terrified of each other together (I am afraid I won’t get what they’re trying to do and they are just as scared of the same thing). This means that as soon as we hit the first idea, the first bit of evidence that we understand each other, we are so relieved and just happy that the rest of the session becomes a bit of euphoria. This process made clear to me how much we need each other – the writer and the reader, whether that be of words, of paintings, of sounds.

Sure, art reviews are often purely descriptive devices to get you to go and see x on at x from x until x, but so are music reviews and film festival synopses. Nothing will replace the actual non-verbal art object itself – art (music, film, etc.) is effective and worthwhile precisely because it operates on a completely different plane to the written and spoken word. There are as many ways to process a work of art as there are people looking at works of art. However, though the ‘art establishment’ would do everyone a service by losing a bit of the artifice, it is also up to individuals to trust themselves enough, and to just put in the time, to think deeply about art that they like.

A well-written essay (hell, a well-written caption) is a thing of beauty. It is a work of art. A well-written essay makes me call my sister in Scotland and say ‘DID YOU READ THAT THING?’ and throw my arms up in the air and gasp for breath in the same way that art does. One of the most important parts of writing (and I use ‘writing’ here as an extension of just thinking about something that you like) is not allowing yourself to be alienated by inexperience.

There are novices and there are pros and there are prodigies. The most influential professors I had at community college and university were the ones that had reached this enlightened place where they still wanted to hear about what their students (myself included) were so inarticulately saying. It was that patience and that insight, but most of all their genuine interest, that was perhaps the most valuable thing. There are people out there with maybe some interest in art but no art training at all that are thinking some amazing things, and they might not be getting involved in writing about art because they think – or they are told – that they don’t ‘get it.’ Our lives are poorer and we are worse off for not knowing what these people are thinking.

The most important thing I have learned about the art world (in what relatively little exposure I have had to it) is that the ratio of kind, helpful people to assholes is just about the same as anywhere else. The writing workshops that run during ArtWeek are designed to bring together people that have been writing about art for a long time with those who have not been writing about art for very long, and also with those who have not written about art at all. In them, those with experience reassure you that there are not as many steps as you may think between looking at the art on the wall and writing about it.

Art draws on experience, the artist’s experience and the viewer’s experience, and you may see a lot of art from which you take nothing. The more you see, talk, and read about, the more comfortable you will become. In time, you may even start to enjoy it. But first you have to look.

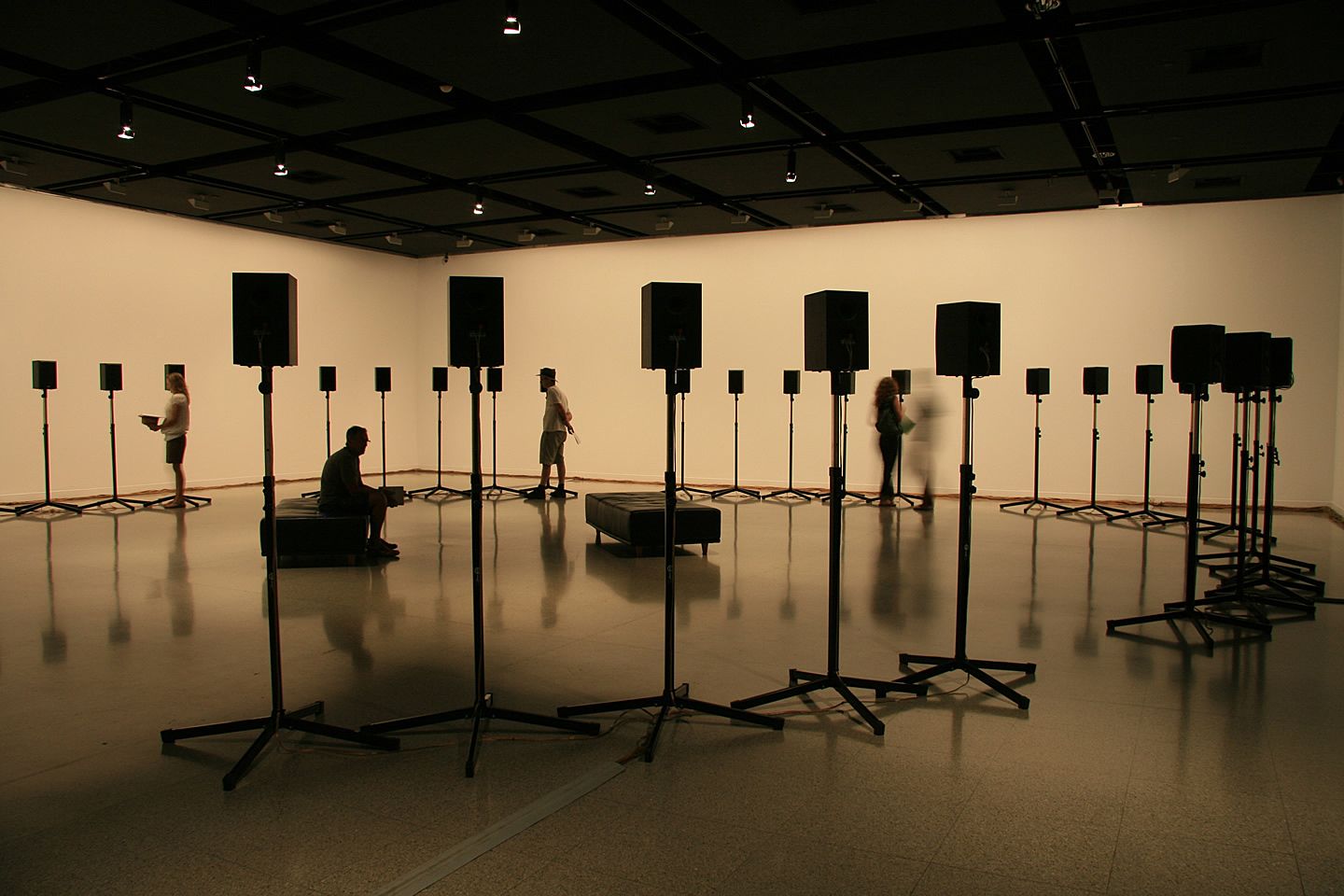

* It was at PS1 in Queens and I walked into a room with 40 speakers playing a recording of a choir singing a hymn, and I just cried and cried (as did another lady in there with her child) and it was one of the most wonderful and fulfilling moments of my life. I later learned that it was Janet Cardiff’s Forty Part Motet.