Legalise It

Thoughts on weed and the referendum.

My friend passes me the smoking blunt, which smells like a mix of grass, sage and damp earth. We’re sitting in a park in the Wellington suburb of J’ville, between the mall frequented by mums sipping on large bowl lattes and the less popular train station, tagged in graffiti. The park we’re in is lovely and empty – it’s 2pm on a Sunday and all the young families are at Muffin Break. I hold the blunt like a precious heirloom, afraid of dropping it, and watch for any shadows of police officers lurking nearby. Cicadas buzz, masking the sound of any ominous authoritative footfall. Our cross-legged circle is sheltered from view by two large pōhutukawa trees.

I’m sitting with her group of friends. I know everyone slightly but not well. Although we’re the same age, they seem much cooler and more experienced than I am. I’m such a good girl, the most rebellious thing I’ve done is be suicidal. It’s my first ever joint. They reassure me that it’s not ‘dirty’; I can’t even imagine what other substances you would mix in here. I have no idea where weed comes from, and how people manage to procure it. I smile and pass the blunt over to my neighbour, letting the others in the circle take a puff before they offer it to me again. I watch the sunlight dapple itself on closed eyelids as she inhales, slowly and practiced. Her chest expands, and her shoulders descend. I place the smoking gun in my mouth and breathe in.

The ceiling is wavy and oscillating. I can feel the sound waves in my body.

One joint split between five people doesn’t equate to much, and I cough most of the cannabis out of my system anyhow. Once the sun has softened behind the clouds we loiter around the streets of J’ville – characteristic naughty teens with no plans before dinnertime. I tug at my friend’s shirt and she falls back a little. “Are you high?” I ask softly. “Yeah,” she puffs back, “are you?” I shrug my shoulders, trying not to seem disappointed. We hurry along to join in with the rest of the group. I borrow her backpack supply of Impulse to spray myself and my belongings.

The next few joints are like this, me pretending something is happening to my body while my brain feels upsettingly standard. One of the cluster of Wellington boys I know reassures me at a party that “the first two or three times are like this”. I cling to this guidance. But how come my friend got high and I didn’t? Is it possible that my brain is one of those rare exceptions where I just can’t feel the same things as other people, and will never be able to experience being high, thus missing out on crucial formative experiences for the rest of my life? I’m informed that I should try holding my breath in my cheeks next time before I exhale, to let the high settle in my airways. I reach for my drink, taking first sips, then gulps.

My first time getting properly high must have been at the start of uni. We puff and pass the joint around until there’s just a blackened stub left, which gets unceremoniously thrown out the bedroom window. Following earlier advice, I bulge my cheeks like a squirrel. The boys peel away and it’s just me and a new friend left, lying on her duvet. I’ve drunk a lot of gin, and suddenly it’s getting to me. The music, which was gentle, is now throbbing. The ceiling is wavy and oscillating. I can feel the sound waves in my body like they’re my heart’s palpitations. My head is a kaleidoscope of sensation. I feel violently giddy. This friend is trying to tell me something personal, something about her relationship. I want to say something kind but my whole face feels distant and far away. Words scratch at my throat, but instead, when I open my mouth I puke down the front of my shirt. Her shirt that I’m borrowing.

*

I’ve gotten used to weed by now; I am no longer puking on other people’s clothes. Imagine if that was taught in health class though, not to get drunk before you start on the blunts. It feels pretty normal to smoke a spliff on a Friday evening, as a way to relax your body against the myriad horrors of the current climate apocalypse. It’s hard to avoid joints, smokes and alcohol in creative-aligned spaces. Even if you’re determinedly sober, you’ll probably still get offered something, at some point.

It’s hard to believe in a future when you’re not able to trust in one.

In an Instagram story for @thebuzzykiwi, Green MP Chlöe Swarbrick says, “It’s really important to recognise that this referendum actually isn’t about cannabis. We’re not inventing cannabis, cannabis exists. It is about how we interact with cannabis. We have a status quo of chaos, where unknown people in unknown places are consuming unknown substances of unknown quality to unknown effect. People keep talking to me about how supposedly we’re gonna open this free-for-all with cannabis legalisation and control. Sorry mate, we have a free-for-all right now.”

I believe that Chlöe Swarbrick is one of the only people currently sitting in the New Zealand parliament who actually understands and represents what young people in the country are facing right now. Young people are facing devastatingly high rates of suicide and mental health issues, a common proclivity for alcohol and other substances, debt, inequality, fears that if the system keeps going the way it’s going we’re not going to have a world to keep living in. It’s hard to believe in a future when you’re not able to trust in one.

Since I was a teenager, a few things have changed around attitudes to weed, although this shocking revelation may still take over a century to reach high-school health classes. For starters, since the 2010s many countries (Canada, Jamaica, the Netherlands) and certain US states have made the move to legalise weed. In other countries such as Mexico, the substance is not entirely legal, but has, at least, been decriminalised (no one will go to jail for growing or using cannabis). Within our own country, weed is still illegal but is deeply embedded culturally, especially among youth populations. Opinions on weed have shifted since my time staring down a whiteboard in a PE class. For example, ten years ago I wouldn’t have imagined posters saying ‘Vote Yes In The Weed Referendum’ comfortably plastered across public spaces, or skin-product brands promoting hemp in their moisturisers.

Perhaps people are wary of voting yes because it feels like we’re inviting our demons to become our flatmates.

For those whose aren’t enamoured of green substances, many fear that legalising cannabis will normalise or even promote the use of the drug among vulnerable populations. People fear that with more lenient cannabis laws, we’ll become a nation of stoners, incapable of doing anything other than getting baked and playing Playstation. MP Chlöe Swarbrick refutes the fear that voting yes ‘normalises’ cannabis: “Between 350 to 500,000 New Zealanders are using [the substances] weekly. The best thing that we can possibly do is take that out of the shadows and start addressing it like adults.” Former Prime Minister Helen Clark extends this argument further in a piece for The Guardian, advocating voting against prohibition, and in favour of legalising and regulating. “Prohibition-based policy approaches have not eradicated and will not eradicate cannabis consumption and supply in New Zealand or anywhere else where its use is established”. Put simply, cannabis won’t disappear from this country regardless of the results of the referendum. It’s whether or not we’re willing to publicly acknowledge the green smoke on our shores.

Another common negative assumption about the referendum is that we’ll be introducing weed to vulnerable populations by making it too easy to buy. Dependent users will increase tenfold, alongside the appearance of neighborhood drug dealers. Toby Morris from The Spinoff does a great job (via colourful illustrations) of disputing this, highlighting the differences between proposed weed laws and our current alcohol ones. It’s going to be very highly regulated in comparison to the nation’s very lax approach around booze and the status quo of cannabis chaos.

Higher safety around cannabis can’t happen if weed is socially present but legally outlawed.

Perhaps people are wary of voting yes because it feels like we’re inviting our demons to become our flatmates. Our country’s already dealing with binge drinking, but that’s an issue we’ll always have, and one that we can’t face without first properly acknowledging it. Higher safety around cannabis can’t happen if weed is socially present but legally outlawed.

As a result of legalisation in other countries, there’s been more conversation appearing globally around the medicinal use of cannabinoids for treating mental health and chronic pain disorders. In incognito mode, I search and learn the difference between the primary cannabinoids in the plant: THC (which gets you high) and CBD (which doesn’t), the latter of which is commonly sold as oil that helps greatly with cramps and muscle pain. As someone with PTSD and period pain, I’d sure like easier access to some of these products. It’s hard to get your hands on either THC or CBD oil in this country. The fact that weed is still criminalised means you can’t just Google the trustworthiness of one dealer over another, or easily compare prices. As the substance continues to be legalised in many places overseas, doctors and researchers are able to study long-term effects on oral health, sleep, behaviour and pain, which will increase our own understanding of the plant’s medicinal uses and detriments.

Despite weed use being widespread across the country, people have a specific impression of a stoner (male, gamer, dreadlocks, bloodshot eyes). Police have a specific impression too, which is mostly just racial profiling against Black and Brown people. While the official numbers waver up and down in correlation with alcohol and cigarette use, the Dunedin and Christchurch Longitudinal Studies show that by the age of 21, 80 percent of New Zealanders have tried cannabis at least once. However, 80 percent of New Zealanders do not have cannabis convictions. Despite widespread use across different age groups and ethnicities, it’s not your friend’s rich white mum who’s at risk of conviction. It’s Māori and Pasifika youth, a profoundly unjust discrepancy of our carceral system. Helen Clark’s essay for The Guardian, alongside other news sources and some classic Insta infographics, emphasises the racial injustices at play. “Without legalisation, major ethnic disparities in arrest, prosecution and conviction for cannabis-related offending are also likely to persist…Māori make up around 15% of the population. Yet Māori aged 17 to 25 make up 37% of all convictions for drug possession.”

Voting yes is an easy way of voting no to colonial racism.

I’ll never forget being at a New Year party and seeing rich white people confidently taking ketamine and ecstasy and acid, with no fear of reproach. No policeman was gonna barge in and forcefully handcuff them. White people are seen as respectable adults who don’t fit the profile of a criminal, so they’re not criminalised for their activities, even if what they’re doing is technically ‘criminal’. It’s funny to consider the weed referendum as a debate in that sense, because for some, weed is already legal, by way of turned heads. The people getting in trouble for drug possession are Indigenous people and Black and Brown migrants, already vilified by our settler–colonial justice system. The fact that the criminalisation of cannabis reinforces this country’s despicable incarceration rates, using drugs as an excuse to lock up Indigenous youth, should be reason enough to vote yes. Voting yes is an easy way of voting no to colonial racism.

I think back to that first joint in my circle of friends, and how my fears of getting into trouble were rooted in fantasy rather than reality. How deeply unjust the foundations of this country are.

*

Of course, there are downsides to smoking weed. No one is denying that these risks don’t exist. Just like sugar, television, sex, work and booze, unhealthy habits can form that affect people’s lives. I know stoners whose memories are scattered all over the place, who anger easily, who drive and operate machinery while high. But as Swarbrick says in the video, “this is not a vote on whether you endorse or support ‘cannabis’. This is a vote on whether you want a sensible mechanism of regulations and laws around cannabis, that enables adults to make sensible decisions and stops kids using early and excessively.”

Smoking weed has been a pleasant social lubricant for me as well as an embarrassing display of my inability to cope.

In the past, I’ve had conversations with naturopaths about how to moderate my own use. When the world turned crazy, getting drunk or high was the only way I could reasonably cope enough to leave the safety of my bed. That developed into a habit I started losing control over, which was disruptive to my body. But don’t just immediately blame that on the bong. Self-medicating is a symptom of instability, and self-medicating populations are symptomatic of unstable systems. The same can be said of higher rates of criminal convictions: what does it say about how we deal with the troubles of our society? Thankfully, I felt safe enough to go to a medical professional to speak on my concerns involving self-medicating with weed when I needed to. We talked about my underlying anxieties and why I was smoking as much as I was. I felt safe enough to let my doctor know that this was a habit they should check in with me about. Imagine if I had felt too villainised to have a conversation with them about my own health.

Smoking weed has been a pleasant social lubricant for me as well as an embarrassing display of my inability to cope. Really good trips are common, where I feel safe and loved. Bad trips are par for the course too, where I can feel anxious and dissociative. How can keeping weed illegal stop some harm from happening, if it’s already in circulation? It can’t. How can we have open conversations on safe drug use if we have created a society so unequal we demand these actions are done in secrecy? We can’t. Legalisation is the best way we can bring these experiences and conversations out into the open, and ensure no one racial group is being demonised for something that the majority does freely, and that everyone is getting the support they need.

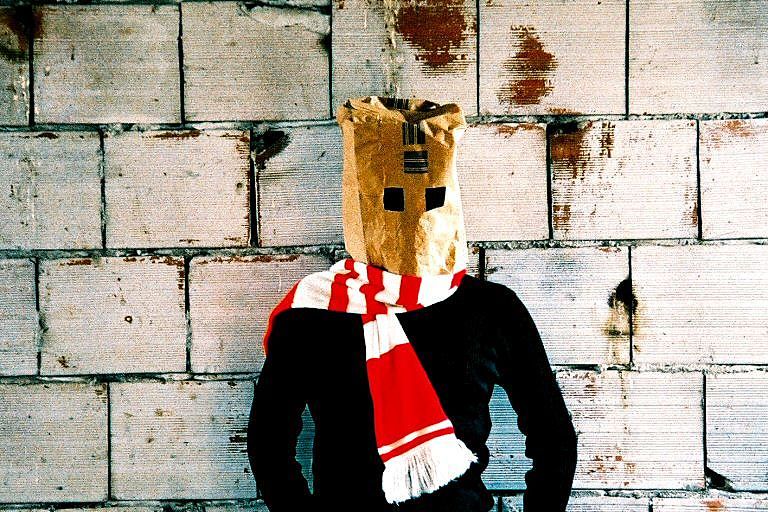

Feature image: ashton/Flickr