“Let Beryl and I sort it out”: On Len Lye and Friendships

Lana Lopesi on Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s latest Len Lye offering.

Lana Lopesi on Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s latest Len Lye offering.

“It makes sense but the … writing is disastrous. Let Beryl and I sort it out….”

Robert Graves in response to Len Lye (as paraphrased from Lye’s own recollection).[i]

When I think of my colleagues, two in particular with which I am in constant conversation come to mind. One recently called me a ‘champion’: while we share an aspiration for #fitspo, I’ve also told her my deepest fears and insecurities about my art and my career. The other recently called me a ‘pillar’: she hangs out with my kids, we Skype often and cry together more than we would like to admit.

While they sing my praises as I go through moments of anxiety, both of them are also brutally honest. Not only are they collaborators on projects which are co-authored, within my own work they are anonymous and unacknowledged advisors and critics that have shaped what it is. Most importantly, they are my friends.

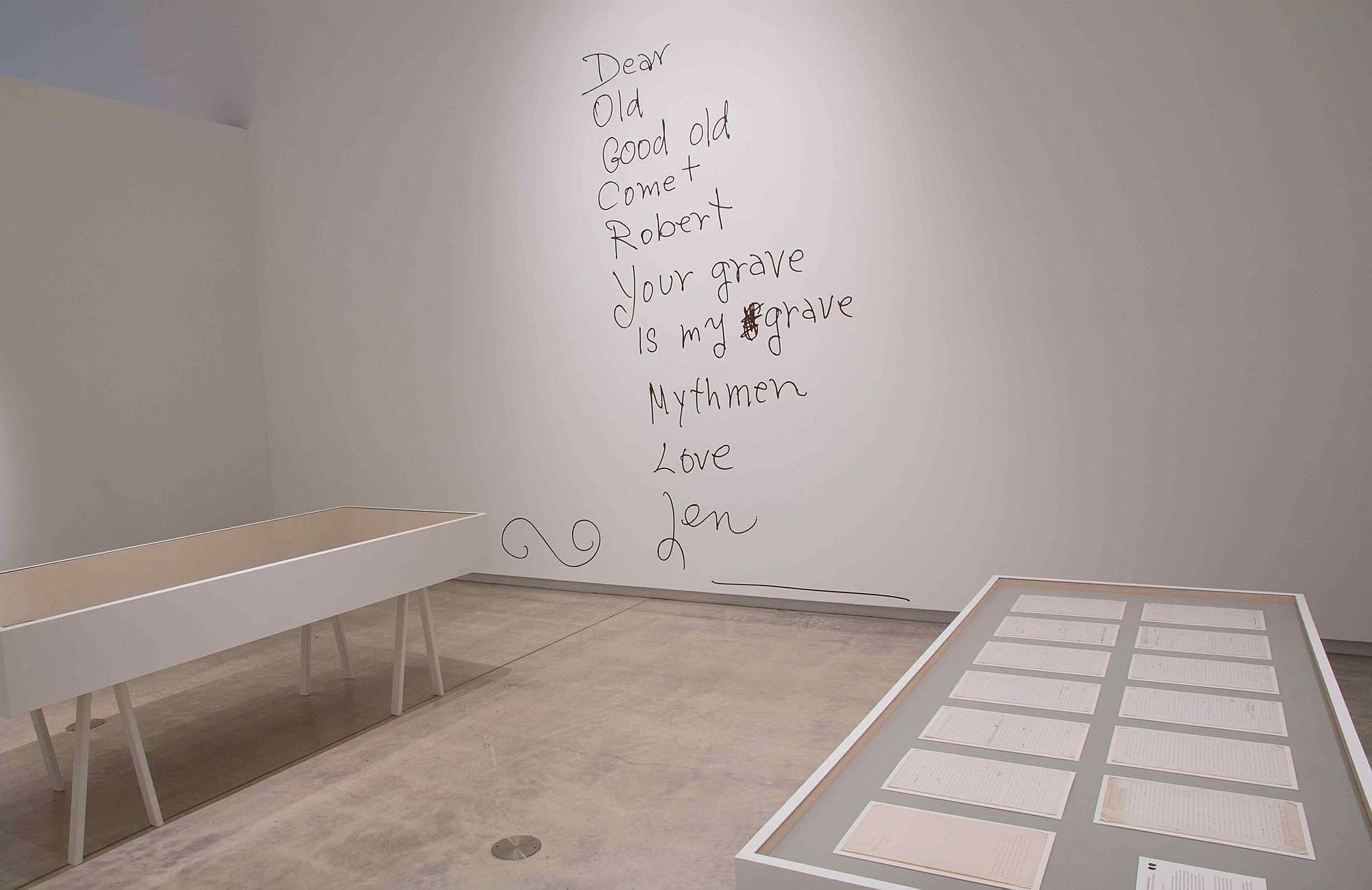

We are introduced to On an Island: Len Lye, Robert Graves and Laura Riding at New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery through the premise of friendship. Curated by the gallery’s resident Len Lye Curator, Paul Brobbel, the exhibition serves as a “survey of works connected to Lye’s stay on the Spanish Island of Mallorca in 1930” in the home of literary couple Robert Graves and Laura Riding.

Before I journeyed to Govett-Brewster to view the exhibition, I read the accompanying publication, ‘Individual Happiness Now’ A Definition of Common Purpose by Lye and Graves. The unpublished essay was written in 1941 to articulate “the freedoms that millions of people were risking their lives to defend, as they fought against Hitler and the Nazis.” In the publicity material, we are told the publication remains relevant today, as “terrorists and extremist politicians are challenging the basic ideals of our society.”

As I read about Lye’s wartime in London, often spent in bomb shelters, I wondered where the hell my bomb shelter will be…

As I read Individual Happiness Now, news was surfacing about nuclear missile parades and testing by North Korea, which in turn provoked ego-driven threats of retaliation aimed at North Korea from the current POTUS. While exploiting the relevancy of this publication is a good marketing plan, it is also a very confronting thought that a World War II text may be relevant to me today. As I read about Lye’s wartime in London, often spent in bomb shelters, I wondered where the hell my bomb shelter will be and how I will protect my children. In their essay, Lye and Graves set to contrast the reactionary rhetoric of the time, which Lye saw as being based on fear, with an articulation of the freedoms that they were fighting for.

The essay is paired with a great introduction by Professor Emeritus and Len Lye expert Roger Horrocks, who sets up both the socio-political situation Lye and Graves were writing under as well as the friendship between Lye, Graves and Riding that formed over a decade earlier. He highlights that while most of the ideas in the essay are Lye’s, it was Graves who was able to articulate his message in a more palatable way. Within the pages, multiple artefacts of their friendship are reproduced: a portrait of Graves painted by Lye; excerpts from personal letters, photos of Lye’s work hanging in Graves’ house; and of course, the photo of the two in Mallorca on the book’s cover. It is this sense of friendship which is carried throughout the exhibition.

I think back to the 2016 Curatorial Symposium hosted by ST PAUL St Gallery, and a paper which was delivered by Indonesian curator Grace Samboh titled Taking and giving: friendship as a way of thinking and doing. She spoke about her curation of The Makcik Project (2012-2014), which focused on the wider Yogyakarta community’s perceptions of transgender women. The first iteration of the project didn’t just involve collaborating with strangers, but using these strangers as the ‘subject’ for the work, a power imbalance which became a focus of Samboh’s.

Over time, she became friends with these transgender women, creating a more genuine collaborative relationship for further iterations of the project. While friendship is a great outcome from any kind of working relationship, Samboh’s friendship model reminds me of the way anthropologists become friends with those who they conduct field research on. This kind of friendship is inevitably the result of some type of research and presentation model, founded the cultural capital of a ‘subject’ – in this instance, their transgender identity.

In stark contrast to the imbalances which Samboh’s talk highlighted are the pre-existing friendships between Len Lye and friends featured in On an Island. The exhibition is littered with quiet pieces of evidence of these friendships and the outcomes of the subsequent working relationships.

The exhibition is littered with quiet pieces of evidence of these friendships and the outcomes of the subsequent working relationships.

The first room doesn’t simply exhibit the collaborative results of friendship, but rather introduces us to Lye’s friends and contemporaries focusing on Lye’s time in London (1926-1944), where he first met Graves and Riding. In this room, we see a painting which was dedicated to Lye from British painter Ben Nicholson. Nicholson was a friend of Lye’s during this time and the two of them were members of the London-based 7 & 5 Society, an art group of seven painters and five sculptors. Sitting alongside the painting is Lye’s first film Tusalava (1929). The primitivist animation borrows from Indigenous cultures from the Moananui region, including its Samoan title. The 9-minute film is made up of 4400 drawings and is a reminder of the modernist thinking belonging to Lye and his friends, and the way the group informed this breakthrough moment in his work.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, it’s rare that Lye stands alone. While on Mallorca, he designed book covers for Graves and Riding’s publishing company Seizin Press, which was founded in 1927. In one of the smaller galleries, the walls are lined with the works used on the various book covers while in the vitrines in the centre of the gallery space we see the books themselves. This room in particular is no way complicated, but it’s perhaps the most intriguing. Not only did Lye provide imagery for the publishing company, but Graves and Riding also in turn helped to bring out the writer in Lye, publishing No Trouble, a collection of Lye’s poetry in 1930. The almost-twee display emphasises the closeness of the friendship while acting as a great example of a co-dependency of literature and art, which will never cease to exist.

Though the mediums have shifted, we still need images to illustrate (either directly or non-directly) our writing, and we need writing that can articulate our illustrations. I think of the way that Anthony Byrt used a still from Shannon Te Ao’s Two shoots that stretch far out (2013–14) for the cover of his book The Model World: Travels to the Edge of Contemporary Art, as an image which embodied his conversation about contemporary art and the "encounters between people and places". At the time, Byrt couldn’t have known that Te Ao’s video work was going to win the 2016 Walters Prize, the coveted award dedicated to presenting the best in New Zealand contemporary art. Yet, he astutely chose this work to illustrate his observations about the state of New Zealand practice after suddenly returning home in 2011 after some time away. The book and the work are therefore given a kind of interdependence, with both being seen as synonymous with Aotearoa’s art ecology circa 2016.

In the next room over, we see portraits Lye made of Graves and Riding. The black and white portraits are tightly cropped around the sitters’ faces. On the one hand, there is a practical and supportive meaning to this. For writers such as Graves and Riding, compelling headshots would have been something – I imagine – would be essential for a publisher’s tool kit – as willing subjects, they also provided Lye the chance to create a new body of work and refine his photographic capabilities.

On the other hand, there is an intimacy involved in having a portrait taken. The power that comes with representing someone and the trust and vulnerability required to allow someone to do that is perhaps another moment where colleagues can shift to friends. The very practice of photographing or painting one’s peers is another testament to the way friendships work and support each other in a peripheral way.

In a contemporary example, Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery curator Ioana Gordon-Smith has had her portrait taken many times by visual artist Janet Lilo. In a recent essay about friendship and art entitled ‘Colluding as curating’, Gordon-Smith picks up on some of Samboh’s models of working where a friendship can offer mutual benefit, offering “a process that deepens an understanding of a practice, for both the curator and the artist”.

But perhaps more interestingly she talks about this friendship with Lilo and their project Status Update, a survey exhibition that was recently shown at Te Uru. Like the friendships between Lye, Graves and Riding, Lilo and Gordon-Smith’s creative outcomes have not been the thing that has brought them together, but are rather the inevitable result of a great working relationship. The kind of relationship which has been formed and strengthened through deep and meaningful conversations, the ability to broach serious ground, the exposing of vulnerabilities and the all-important welcoming of and moving on from conflict and criticism - all of which can only happen over a developed friendship.

Breaking down the idea of the artist-as-island, this exhibition shows how Lye was a part of a wider network and a product of his peers and his friendships.

When I think of Len Lye, my first thought is of loud and or large kinetic sculpture. It’s an obvious missing feature of On an Island, as he didn’t start to make these best-known works until his time in New York from 1944 until his death. Instead, the quiet and reflective nature of this latest exhibition is a great new avenue into some of Lye’s early works. Breaking down the idea of the artist-as-island, this exhibition shows how Lye was a part of a wider network and a product of his peers and his friendships. The power lies in the opening up of his work and his thinking – showing that it was not just his, but belonged to a wider collective group which participated in a culture of open and meaningful exchange. The notion of friendship at its essence is very simple, but its effects when lain bare like this can be profound. This exhibition highlighted just how much better our friends make our work either in public or private. While it is often a singular name that ends up attached to a piece of art or literature, the influence of peers, friends and family is undeniable in any creative practice. It’s refreshing to finally see a show about it.

On an Island: Len Lye, Robert Graves and Laura Riding

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

8 April 2017 – 6 August 2017

All photographs courtesy of Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

[i] Wystan Curnow, ‘An interview with Len Lye’, Art New Zealand, 17, 1980, p.61.