Loose Canons: Courtney Sina Meredith

Writer Courtney Sina Meredith on the streets and stories that inform her work.

Loose Canons is a new series in which we invite artists we love to share five things that have informed their work. Today we talk to writer, performer and red-lipstick-sporter Courtney Sina Meredith.

Courtney's first book of poetry, Brown Girls in Bright Red Lipstick, launched in 2012, but by that time she had already established herself as an integral member of New Zealand's literary community. Her play Rushing Dolls (2010) won a number of awards and was published by Playmarket in 2012, and selected by Silo Theatre for Working Titles 2015. She was the Bleibtreu Berlin writer in residence 2011, a delegate to London for the British Council in 2012, a guest of the BBC to the House of Lords in 2014 and she has an upcoming residency in Sylt (Northern Germany) for 2016.

Her poetry and prose have been translated into Italian, German, Dutch, French and Bahasa Indonesia. These days, she's working on her first collection of short stories, Tail of the Taniwha.

Courtney is one of the panelists in our upcoming event The Kill Screen, where four creatives will chat about when their muses are kind, and when they must die.

Lemi Ponifasio

I met Lemi when he was working with my mother on a show. It was the way that he spoke with his entire body that truly struck me. They would have meetings and I would go along with my pens and paper to draw (I must have been around 7 or 8), but their conversations always drew me in.

Lemi inhabited a world without walls, without rules, without limits. Everything was just a decision away, including the person that I wanted to be. That was raw power, standing in the va and staring back at myself as an ancient technology. The role of the artist is to create change; to observe; to be at the back praying and to be at the front fighting. Many of my foundational understandings as an artist have evolved from Lemi’s philosophies around thought and divinity.

By the time I was 24 I had written a fair amount of content and gained considerable traction as a performer. I read at the book launch for Mauri Ola which Albert Wendt, Reina Whaitiri and Robert Sullivan had published me within. I didn’t know that Lemi was there listening at the back of the room. Afterwards he came right up to me and said that he was going to take me to the top of the world into the grandest theatres to share my work with the gods. A few months later Lemi contacted me from Paris and said that he had gotten me a writer’s residency in Berlin. That residency changed my life. It involved long days in the dark watching dancers and gypsies and singers move across the stage in dim light. There were lunches with international authors and interviews with international media. I wrote constantly, taking journals with me everywhere: into clubs, into galleries, into restaurants, into the fresh morning light of the Tiergarten. My life has never been the same since.

Karangahape Road

In my mid-twenties I ran with a formidable wolf pack. We were young brown women interested in social justice, amplifying our lives through art. Together we made a short film about Maori and Pasifika night people along K Road. That project saw us befriend strippers at Vegas show girls and I wrote plenty of poems smoking with the girls back stage, watching them get ready for their sets. I discovered what smart mothers and sisters and daughters they were.

With them I learned what it means to get up and say that you represent your ‘people’. Your people aren’t just the shiny faces you want them to be. You are plaited within a social fabric so beyond your comprehension it takes research and guts to locate yourself within it. We sung a lot of karaoke, climbed walls and broke hearts. We were committed to sharing the stories of people living rough – living tough.

In the end we presented that film at an arts fono and we got a lot of positive feedback from established artists. I think it shocked people. After we screened it nobody spoke.

K Road is all through my book Brown Girls in Bright Red Lipstick and my play Rushing Dolls. I lived in an apartment there by myself for a year when I was 25. I learned a lot while watching people scavenging for food in the bins across the road. I learned the space between dancing and prostitution, working and scavenging, succeeding and failing – that the 'Promised Land' is what you make of it.

Fake Plastic Trees by Radiohead

This is the song that gave me ‘Rainbow’s End tummy’ when I was 11 and we were living on Russell Street in Ponsonby. My mum got this awesome vintage speaker, she linked it up to a CD player in her bedroom and kind of drip fed me haunting odes, ballads, crushing African drums, a lot of James Taylor and The Cranberries too. Thom Yorke quickly became my hero.

I remember taking The Bends to a friend’s 12th birthday party. She was a fan as well. We put on ‘Fake Plastic Trees’ and screamed out the lyrics at the top of our lungs while jumping up and down on her trampoline surrounded by gobsmacked classmates.

I like how kaleidoscopic Radiohead are with their arrangements. Nothing is leading or following, you aren’t sure whether Thom is the vocal or the crazed indefinable pulse between notes. Thanks to him I have an obsession with wrapping my voice around spaces, when I’m performing my poems – I’m really just trying to make every word that leaves my mouth reach the other side of the room, and up into the ceiling, and under the floorboards. I’m a weirdo, I walk past buildings that I’ve performed in and I think of all my words rattling around in the walls.

Red Lipstick

My mother wore red lipstick from Zambesi when I was a girl. It was a piece of gold that I had to help her look for every morning. The scene often changed as we moved around different flats across Auckland, but the treasure hunt stayed the same.

I liked being the one to find it, proudly watching her put it on in the hallway mirror or the bathroom mirror or the rear view mirror. She looked so beautiful it used to stun me. When my grandma was alive she flitted between bright purples and pinks and reds now and again. Her lips changed with her mood. I remember her coming into Glen Innes kindy when I turned five and was ‘graduating.' She had an electric mauve smile with a box of Cadbury continental chocolates in her arms.

There’s something deeply sentimental about red lipstick for me, it stands for sassiness and beauty but it’s also what Samoan women mark their face with before performing the siva Samoa.

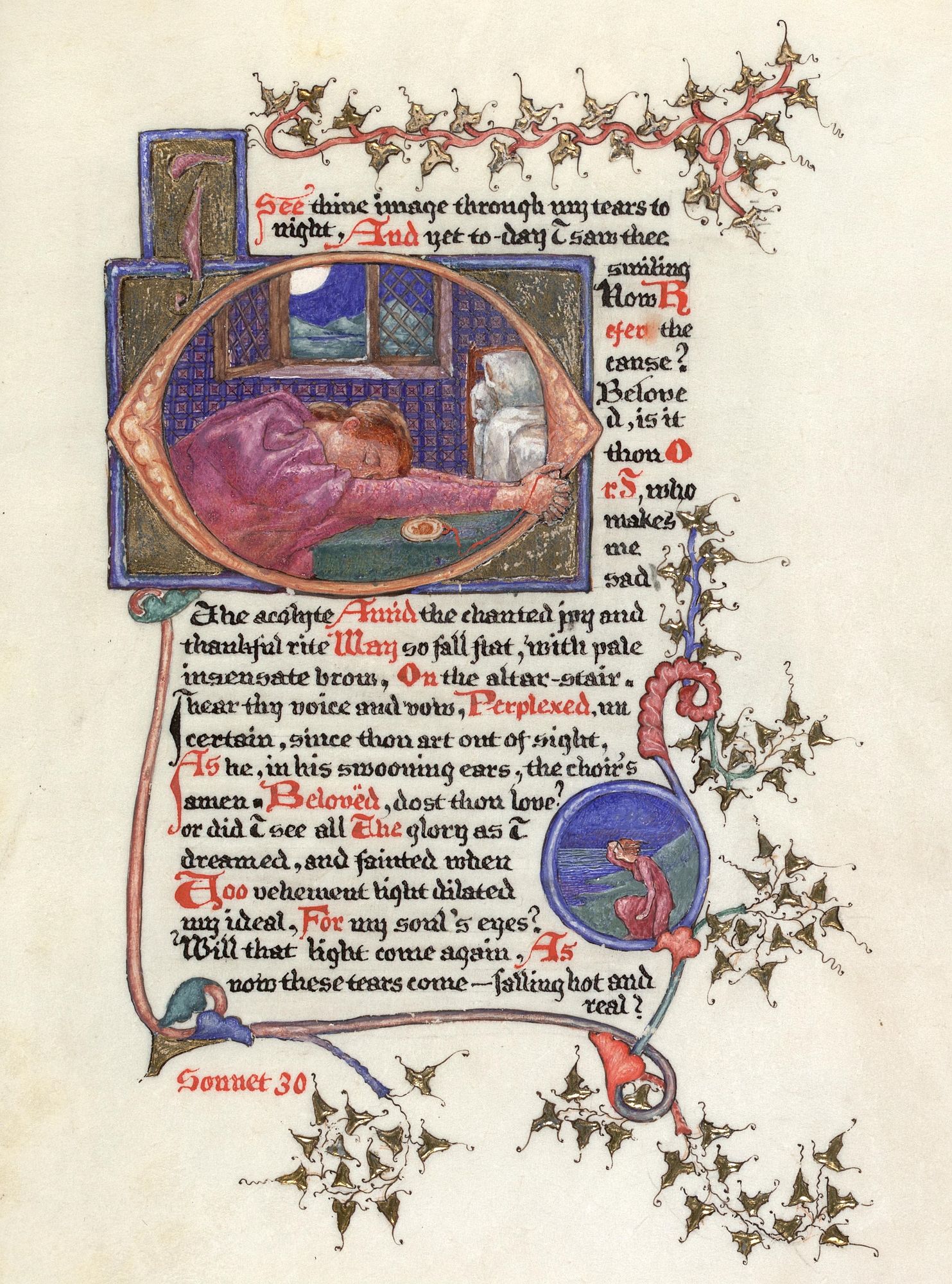

Sonnets from the Portuguese

Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote Sonnets from the Portuguese for her husband Robert Browning. They were so intimate that she didn’t want to publish them. Her husband encouraged her that they were the finest sequence of sonnets since Shakespeare.

In the end she decided to publish them as though they were translations (from the Portuguese!). A couple of things grabbed me around the neck about this, as it was an echo of conversations I’d had with my mother. I thought that great art had to focus on great events, but my mother (a fantastic writer herself) urged me to see everyday events as great. I would never have written so close to the bone, if I hadn’t discovered for myself that quite possibly the most beautiful work I’ve ever seen on the page began in the smallest and kindest of moments between two people who loved each other.

Hear more about Courtney's process and creativity at The Kill Screen on the 17th of September at Q Theatre. Header image by Ali Ghandtschi