Mana Rangatahi: Young Māori on Standing with Ihumātao

Ten rangatahi Māori on what standing with mana whenua at Ihumātao meant for them.

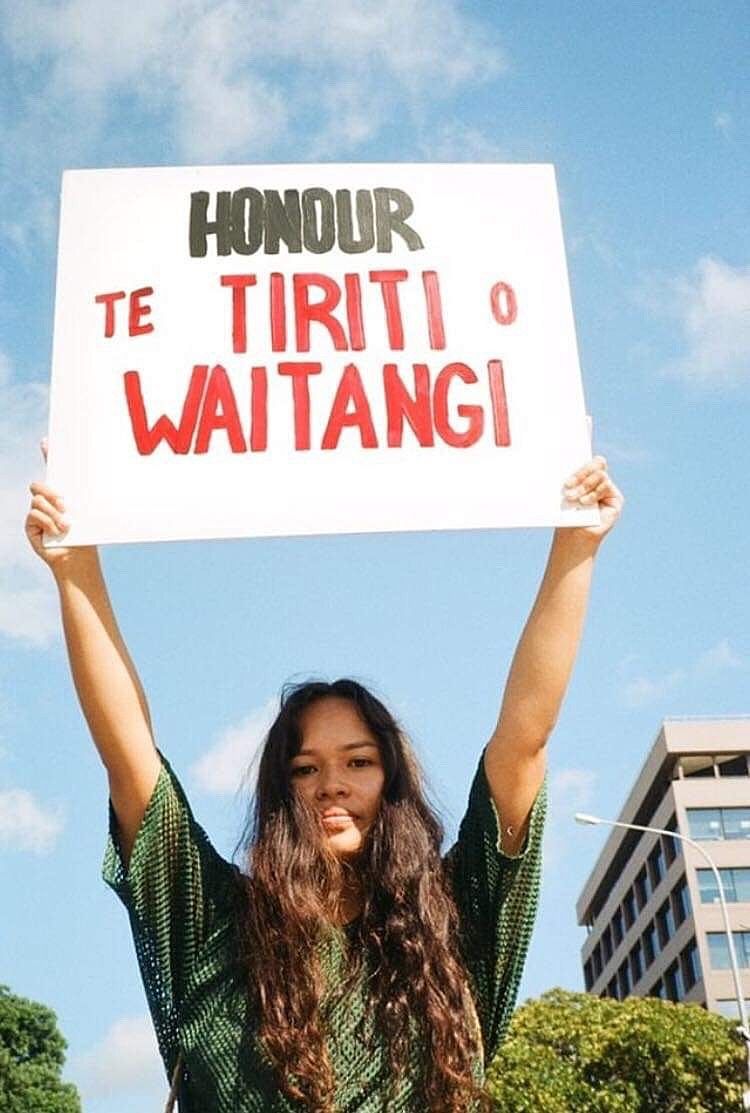

Over the past couple of weeks, a shared sense of urgency has drawn thousands of people of all ages from around Aotearoa to support mana whenua as land protectors at Ihumātao. Here, ten rangatahi – Tayi Tibble, Sinead Overbye, Jessica Thompson, Michelle Rahurahu Scott, Himi Grace, Miriama Grace-Smith, Bionica, Trinity Thompson-Browne, Nicole Hunt, Kahu Kutia – say what being at Ihumātao meant for them.

After a long weekend with the whenua, I arrived back in Te Whanganui a Tara exhausted, but with my heart so full that it hurt. It grieved. I didn’t want to leave because, despite the serious circumstances in which we were all gathered there, to protect Ihumātao, it was like being in a decolonised dream.

Unfortunately we still live in a colonised system and I had to get back to work. Make money. Pay rent. That dated capitalist grind. So I shucked off my backpack and the Bob Marley tee I had worn for three days straight, and immediately got into bed. However, as tired as I was (plus lowkey relieved to be on an actual mattress) I couldn’t sleep, I was still charged with the same anxiety, with the same urge to do something, with the same unrest in my heart that had compelled me to go to Ihumātao in the first place.

I had thought that if I went and stood with the land, the urge would ease. I thought I would feel relief. I thought I would be able to sleep. But, despite colonial attempts to “smooth the dying pillow” many Māori have never been able to rest. Ka whawhai tonu matou. For as long as there has been colonisation, there has also been resistance; a rich history of fighting for tino rangatiratanga. So, the urge still burns, and will continue to, until Ihumātao is returned, and until all indigenous land, rights and knowledge are respected, globally.

As the climate situation grows more and more precarious, Papatūānuku’s call to us, as indigenous people, as kaitiaki, becomes more and more urgent, and difficult to ignore. We feel the call in a way that is hard to articulate; so deeply, that it is difficult to fish the words to the surface. Because it’s in our blood. It’s in our history. It’s in our whakapapa. It’s in our ability to trace ourselves back, right back into the womb of Papatūānuku and understand that the land is the mother of our culture and that we are her descendants. This is what it means to be indigenous. This is why our ancestors lived by and died for the whenua with same aroha and dedication one has for their own whānau. This is why Māori are so invested in the land, and this is part of the reason why Ihumātao has become so important not only for the mana whenua, but for many Māori across Aotearoa, as a place to come together and to make a stand, with the land, not on it.

In a society that likes to paint both Māori and Millennials as disinterested, disengaged, and apathetic ... it was fucking epic to see so many young Māori answering the karanga, turning up for Ihumātao with so much grace, swag and mana.

The purpose of land alienation was also to alienate Māori from each other: if the land is the heart of community and culture, what happens to culture and community when the land is stolen? In reality there are so many excellent young Māori out there doing amazing things, in a white world, surrounded by white ideas and um, white people, but it is easy to feel alienated and alone as Māori, as if you are the only one who experiences and understands the world as you do.

What Ihumātao proved was that this simply wasn’t true. When I was up at night racked with anxiety, other rangatahi were too. When I was glued to my phone checking for and posting updates other rangatahi were too. When I not only heard the call but felt the call, other rangatahi did too.

In a society that likes to paint both Māori and Millennials as disinterested, disengaged, and apathetic – only self and social media obsessed – it was, for lack of better words, fucking epic, to see so many young Māori answering the karanga, turning up for Ihumātao with so much grace, swag and mana. I burned with pride as I witnessed dope, woke rangatahi mobilising and advocating for Ihumātao and indigenous rights both irl and online, holding it down on every front line, bypassing traditional media outlets, (who um cough, have not always been the most friendly or flattering towards Māori), and putting information out themselves via posts and updates and livestreams. In keeping up to date about Ihumātao, I don’t turn to television, or radio or the news etc, I turn to them.

So when I couldn’t sleep, when that same ancestral pulse was keeping me up, I drafted a DM to a bunch of the e hoas I had seen occupying both the whenua and online, and asked them if I could ask them a few questions about their experience at Ihumātao. Because the truth is, even though I’ve tried, I can’t really explain what Ihumātao is like, or what it means, what it feels like, especially to rangatahi Māori. And although I am whakamā to say it, I feel like I want to say that something feels revolutionary. Perhaps in 40 years or so, when I will have ripened then shrivelled into an old wise kaumatua, I might have the words to really describe what Ihumātao was like, but I can’t right now. So, I asked for their help. And as their responses started coming in, I couldn’t fight the ache in my throat. Moved by their generosity, aroha and intellect, I wept. This is what they said.

–Tayi Tibble

Sinead Overbye

Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki and Rongowhakaata

@applecarcass

I went to Ihumātao because I was lonely. Everything – my friends, the news, social media – was too silent on the subject, and I was deeply uncomfortable with that. I felt constantly pulled towards the whenua although it isn’t mine. My tūrangawaewae is in Te Tairāwhiti. And yet, I sat in my office watching videos of the police moving in, and thought, I’m not where I’m supposed to be. I saw history repeating. I felt distraught at the violence and oppression that has shaped, and continues to shape, this country. And I wanted to know exactly what was happening. And I wanted to be with people who understood how I felt.

But still the news stayed silent. I saw other rangatahi posting about Ihumātao, to educate people, and the rest of social media not saying anything in response. I grew tired of the silence.

So I went to Ihumātao. I stood on the whenua and pitched my tent, and I knew that my body would be counted. That my physical presence was powerful enough. That’s all that is necessary really, to tautoko the cause, is just to show the fuck up. I handed over a supermarket bag full of kai and a box of water bottles, and was greeted with a kihi, a hug, and an enthusiastic ‘ngā mihi!’

And my anger dissipated. A great sense of calm washed over me. Ihumātao was so peaceful, and there was nothing but joy in the atmosphere. We sat outside our tent watching people spin poi and tamariki play soccer, while we listened to our childhood songs blasting over the loudspeakers. People carried buckets of fruit and trays of sandwiches and bottles of water all around the field to make sure everyone on the whenua was nourished and hydrated. And we laughed and we talked and we sang. And if it wasn’t for the line of police officers just metres away, it would’ve felt like a huge party.

That night we woke every two hours to carry flasks of hot tea to those who were guarding the frontline. They sat in front of the pirihimana and chatted, even though their bodies shuddered with the cold, even though their breath was icy. And in the morning, when Pania called that there would be 1000 manuhiri arriving soon, and to expect thousands more to come through, we sat in a circle outside the kitchen tents and peeled potatoes and talked to the others in the circle about where they had come from, and why they were there.

It was a weekend filled with special moments. One thing I will never forget is digging a hole into the earth, and planting a rākau at the feet of the pirihimana to let them know, this is the barrier now, we have pushed back, and whatever happens we will always be here.

I want to start a conversation, to break the silence.

The morning we left, we woke to the sound of laughter. After packing up our tent, we walked to the laughter’s source and saw police officers and mana whenua playing a game of ‘headbands’ across the frontline, keeling over with laughter. Michelle and I wept because we didn’t want to go. The world outside Ihumātao isn’t so peaceful or caring. We wanted to keep protecting the whenua forever. We bent our heads towards the ground and said a karakia, for the cold winds to stop blowing, for a gentle breeze to flow over sea and land, for the reddened dawn of a glorious day.

I don’t want to die having fought for nothing, having done nothing, having believed in nothing. There is a revolution taking place, and it is being led by our rangatahi, I really do believe that. That’s why I went to Ihumātao. I want to be a part of that revolution. I want to start a conversation, to break the silence. I don’t want to sit back and let this pass me by.

Jessica Hinerangi

Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Ruanui

@maori_mermaid

I hadn’t been able to focus, eat, or sleep, since they announced the police had served the eviction notice and people were getting arrested. It felt like the violations and scars embedded in my whakapapa were inflamed, someone had pulled the stitches apart in the middle of the night and rubbed salt on the wounds. I had never been to Ihumātao before but for a lot of people this situation goes beyond direct iwi ties to the specific place. We feel this fight for the land in our Wairua, we feel our own personal and whānau losses in the symbol that Ihumātao has become. We are bonded as one, and kōtahitanga reigns beyond our differences.

I went to Ihumātao to be present and stand, not only for this particular piece of land, but for my whakapapa, my tīpuna, and future mangainga of Aotearoa.

My whānau are originally from far north in Rawene, Hokianga, but we ended up spreading out in the First World War. My great grandmother, Maraea Koroneho, lost her land when her husband died. My Māori whānau have been scattered over Aotearoa, and we have been struck with disconnection and displacement for years. I went to Ihumātao to be present and stand, not only for this particular piece of land, but for my whakapapa, my tīpuna, and future mangainga of Aotearoa.

On the 25th of July I arrived at Ihumātao, quite last minute, having jumped onto a plane (flights kindly provided to me by Action Station NZ) straight after work. Upon my arrival, the police had moved forward before sunrise, taking more of the field space, despite agreements not to. We stood in a line and spoke to them. This was the most emotional experience I’ve ever had. From here on I gave my body to the barricade, live streamed the situation, and helped members of the media/communications team with small jobs such as banner painting, raising the tent, fetching kai and coffee, and relieving people of their stations. I tried to give what I could, and ended up getting so much aroha and knowledge in return. You feel it as soon as you get there… the land is truly sacred, it fills you up, cleanses you, and gives you strength. It is vital that we maintain the unity and manaakitanga that has blossomed from this moment in our history, carry it to the future, as far as possible. And if you can, make the journey to be with the whenua.

This will be going on for some time, and it is important not to let it fade from our minds and hearts. This is not a trend or a fad that will pass, this is conservation, spirituality, basic human rights, and tikanga. What is going on at Ihumātao has been going on since Aotearoa was colonised. Technology and social media have just made it harder to sweep the situation under the rug.

Michelle Rahurahu

Te Arawa (Ngāti Tahu-Ngāti Whaoa, Ngāti Uenukukopako, Ngāti Tuwharetoa), Tainui (Ngāti Raukawa)

@_wyvern_

I’m usually so apathetic – “the world is ending, I’m powerless, etc” – but Ihumātao pierced my hardened skin. I was compelled to go in person and saw the value of getting engaged even if you’re young or don’t know what’s up. How are you supposed to learn if you don’t show up to the hui? Thank god I did because the kōrero is a huge Venn diagram of inter-iwi/hapū/generational struggle – feminism – de-colonisation – Māori agency – politics in a digital age – and then in the middle is systemic racism crossing all of the circles. The kōrero is holistic and it feels like action here means action in every circle, which fires me up!

I arrived at Ihumātao and it was like a reunion – some relatives were there, like my matua Erueti and of course I have investment in the whenua but everyone treated me like a whānau member. It’s so de-colonised!

Visitors get to see the purpose of māoritanga in action – not as a concept or a performative action inside a Pākehā space. I saw where waiata, haka, karakia fit in – how manaakitanga fits in – how pōwhiri fits in. Where tāngata of all ages and backgrounds fit (spoiler: anywhere they like). How different whare are organised. He tāngata, he tāngata, he tāngata. Everything’s based on necessity and a history of effectiveness – that’s where tradition fits in.

The biggest part is that the social aspect is about closing gaps between each other (a friend once told me). Which is hella practical. How are hundreds of people supposed to get along if we feel far apart? So yeah you treat everyone with familiarity and respect – the receivers kiss the cheeks of strangers – the visitors offer help and resources before they’ve met anyone and pick up mahi without being told. Kuia ask people where they’re from – not what they do. Closing gaps. Those who are well integrated in these customs understand this but I could see how active participation teaches those who aren’t – there’s no rulebook at Ihumātao yet people follow. I reckon that’s why the occupation has worked well so far – by inviting participation and leading by example.

You see a hundred voices saying different things which only makes the kōrero richer.

But not everyone can be there so it’s important to keep a digital occupation too. Otherwise you render the mahi meaningless. Social media is our best tool for getting info around fast and represents how complex our people are. Māori voices are often lumped in one homogeneous camp. We don’t all think the same! We don’t have to! You can see that on your feed if you engage. You see a hundred voices saying different things which only makes the kōrero richer. We all contribute to a larger conversation and every word we say – right or wrong – is part of a public brainstorm. We’re talking it out together in digital space so keeping quiet is killing the kōrero and metaphorically walking off the whenua. I’d encourage everyone to like... not do that.

Himi Grace

Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Porou, Ngāpuhi

The rangatahi response to Ihumātao has been the most inspiring movement of my lifetime. It’s like this has reawakened our generation’s political consciousness. Mana wāhine leadership is shifting the paradigm for all of us on a global scale, and for the first time the idea of indigenous mana motuhake has become mainstream.

We came from all winds to protect a whenua regardless of whakapapa links. Because this has become far bigger than the land itself. Unlike the spiritual imbalance that is killing tāngata whenua, leaving us homeless, locked up, Ihumātao is a straight up example of colonisation that we can point at, and fight. A fight that can be won. And if the mana whenua do win, so do all of us.

Someone tried to tell me the other night that Ihumātao was just Māori vs Māori problem. But it wasn’t tāngata whenua who stole the land in the first place. This raru was caused by the Crown, regardless of what the news tells us. This is the continuation of colonisation born from raupatu, and Fletchers’ actions are no different to the New Zealand Company; buying land they have no right to and using the colonial government to evict mana whenua who refused to leave.

I feel kind of whakamā writing this as a person whose place of employment is the very representation of colonisation. I might work at Parliament, but I don’t necessarily work for them. They pay me, and I use their resources to work for my people. So I turned up equipped with a camera and the tools of my job. This meant MPs and a media platform to amplify our message. When I had done all I could from that side of things, I turned my phone off and joined the front line.

I couldn’t help but laugh at the beauty of what was happening all around me.

I took a lot more away with me than I brought. I was completely at home and I am anxious to get back there asap. I can’t even describe the sense of pride and fulfilment I felt. I was well fed, entertained with poetry, dancing and waiata, and was given enough blankets to build a fort. The kaitiaki embodied manaakitanga and aroha in the face of colonial repression. I couldn’t help but laugh at the beauty of what was happening all around me while staring at a wall of stone-faced cops.

Today’s movements are built online. Being there in person is always the best thing you can do, but without online advocacy most of us wouldn’t have known where to be and why. For anyone who can’t be there in person, make your voice heard online. And if you are there, post about it online. Showing your friends you care about something makes them see it in a different light. It might make them curious enough to learn more, and to turn up themselves. Everyone wants to be part of something, and social media can connect us no matter where we are. But I can’t stress enough being there in person and feeling the wairua of that sacred whenua for yourself.

Miriama Grace-Smith

Ngāti Hau, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Toarangatira, Ngāti Porou

@miriamagracesmith

It was important for me to go to Ihumātao to place my feet on the whenua. I couldn’t handle it any longer, stalking every social media update. I found myself feeling anxious, tired and angry. I thought about how our tupuna fought for our whenua, died for our whenua! Me jumping in a car or jumping on the next flight to Auckland broke af, was nothing compared to what they went through. So with just a backpack each, pohara as, my friend Tayi and I bought the cheapest one-way tickets and jumped on a flight.

We didn’t have much but we arrived willing and ready to give what we could and help where help was needed. But when we arrived we felt as though we were the ones that received more than we gave. When we stepped in those gates, it felt like we had stepped back in time, to when our people worked harmoniously together. The manaakitanga and wairua of this place was overwhelming.

I’m an artist, the way I express how I feel and try to give back is through my art. I feel as though I didn’t do enough when I was at Ihumātao, but I feel grateful I was able to leave something behind. A mural, an expression of my aroha that I have for Ihumātao and the people working tirelessly every day and night to protect this beautiful whenua.

This event has made me think about the constant battles we go through everyday being Māori, how normalised the feeling of being too tired to fight anymore becomes.

I learnt so much from my experience at Ihumātao. Something that has really stuck in my mind since leaving is how important it is that we keep fighting, not just for our whenua but for our people. At least once every two weeks I come across someone who challenges me as a Māori working in the creative industry, and it is a constant tiring battle sticking up for myself and for our people. This event has made me think about the constant battles we go through everyday being Māori, how normalised the feeling of being too tired to fight anymore becomes. We are always having to stand up for ourselves, to be who we are, to protect our whenua, our work and to do what we love! And it gets so tiring, but it is so important that we keep fighting and never give up to pave the way for the next generation and hope that one day, we will no longer have to fight.

This is what I have learnt from my time at Ihumātao: Ka whawhai tonu matou – Struggle without end.

Bionica

Ngāti Whātua, Ngāti Porou

@_bionica_

Activism is in my blood. My mother cut her teeth at Bastion Point and my grandmother has always been active in the South Auckland community, so fighting for indigenous rights, womens’ rights and climate change has always been centred in my family. So it wasn’t a choice to tautoko SOUL and the mana whenua kaupapa; protecting the land from development. Being immersed in te ao Māori at Ihumātao is a gift the papakāinga has given me. It is humbling, especially having grown up divorced from that in Melbourne.

At Ihumātao friends and I set up a takatāpui camp in line with the kaupapa, so that like in pre colonial te ao Māori , there would be a safe space for all to be present and protect this whenua. But the most important thing while I’m at Ihumātao is to ensure that I am doing something. Being in the kitchens, sitting on the front line, maintaining the ahikā at Camp Gay.

Being at Ihumātao is visceral. Your heart is warmed by the waiata and the laughter of tamariki.

I can’t articulate how both nourishing and draining it is to be active in fighting modern day colonisation. Being at Ihumātao is visceral. Your heart is warmed by the waiata and the laughter of tamariki. But then your stomach drops when you notice the numbers of police officers or the sentiments of mainstream media or the piss poor reaction by Jacinda.

Just like what is happening with Mauna Kea, this struggle at Ihumātao elucidates that colonisation is a noxious weed whose roots are deeply entrenched in this society and not some long forgotten lover of the past two centuries.

Trinity Thompson-Browne

Ngāti Kahungunu

@trin_tb

I spent my birthday that I don’t really tell anyone about, working alongside people I adore at Ihumātao. Mihi out to my mates, they’re beautiful humans inside and out. Anyone who knows me, knows I love to friend-match my mates and Ihumātao was perfect for that, while we are here, standing up for tino rangatiratanga – the freedom to be self-determining over the outcomes we want for our own lives.

If we all waited for Crown breaches to directly affect us, we’d be a lot fewer, a lot weaker and a lot lesser as a people.

Ihumātao doesn’t need to be our whenua or our whakapapa for Māori everywhere to stand up and tautoko. If we all waited for Crown breaches to directly affect us, we’d be a lot fewer, a lot weaker and a lot lesser as a people. Our power comes from our collective nature, we draw mana and mauri from each other and that keeps us strong. Being on the whenua as kaimahi, we uplift and hold space for each other as we work towards our collective goal of supporting mana whenua in their aspirations for Ihumātao. Because if the hū were on the other foot, that’s what we’d want if it were our whānau, our hapū, our iwi.

Aside from feeling the most satisfied I’ve ever felt from protecting the whenua, the whenua gave so much of herself to healing the heartbreak I’ve been nursing; for that I will always be grateful. It’s now obvious why everyone has so much empathy for this particular mamae; though no fun, we live, learn and grow.

Nicole Hunt

Ngāi Tūhoe and Te Arawa

@locapinay

Tāwhirimatea picked up his pace this week and our tents are struggling against his force. I like to think he’s preparing us for storms to come on other fronts. Thousands have been walking across Papa here and turning her into mud, but the trees we planted will long outlast our pop-up pā. The mist of Hinepūkohurangi was so thick on the first few days that she cloaked us from police when we walked the whenua. Our tīpuna have been working alongside us this whole time.

If you have a basic understanding of Māori history, you’ll understand why we’ve been turning up in the thousands for this. I struggle with the Pākehā tendency to be unaware of the connection between the desecration of our land and the consequential damage it has to tāngata whenua. Our culture was developed over centuries of living with this land, so it’s no wonder we’ve become so disempowered after centuries of purposeful alienation from it by the Crown.

There is also a strange separation that exists between indigenous people protecting their lands and the global issue of climate change. As necessary as it is to push for reusable straws and eco friendly clothing, movements like Ihumātao are at the very frontline of climate change action. These movements have always been led by indigenous people, and it is our wāhine in particular that have been putting their bodies on the line for our whenua time and time again. The silence of Pākehā, especially those who project a nature-loving image, has been disheartening.

As images of policemen holding our babies roll out, I will never forget running from the frontlines to the field as they closed in on our tents at dawn. I will never forget linking arms with my sisters, yelling their mamae out, while the Crown marched towards us. I will never forget the smirks of Pākehā officers as we spoke our truths kanohi ki te kanohi.

Ihumātao has given us the chance to lead the way in reimagining a future for ourselves

The revolution looks like roasting marshmallows at your campfire instead of going to your day job. It’s free daycare, a koha economy, daily wānanga and the acceptability of greeting a Queen while you’re wearing sweatpants. Ihumātao has given us the chance to lead the way in reimagining a future for ourselves, and what a beautiful sight it has been.

Never before have we been able to bypass our Pākehā-governed media and control our own narrative while we exercise tino rangatiratanga. Our storytellers and artists have been vital in pushing our truths and mobilising our people through social media. I urge you to stand in solidarity with us, be it on the ground or as digital kaitiaki, as we continue to disrupt these systems together.

Kahu Kutia

Ngāi Tūhoe

@kahukutia

Everywhere I go I feel the price of colonisation, climate change, capitalism. Three things that are intimately connected. We owe a huge debt to Papatūānuku, and while it was not indigenous people that caused all these problems, it is indigenous solutions that can fix them.

Being on the verge of Auckland city, Ihumātao has already sacrificed too much for the supposed “greater good”. Their maunga tapu have been quarried to nothing. Their land was stolen from them. Their ancestors have been dug from the earth to build an airport runway.

One of the things that Pania says is that she is willing to die for her whenua. I resonate with that. Deeply. If my whenua had gone through what hers has, if my whenua was under threat like hers is, no doubt I would put myself on the line.

Though all credit to Pania, not everyone could do what she has done. This kaupapa was founded by six mana whenua cousins with the support of their marae and kaumātua, but the leading role that Pania has inevitably come to fill could not be done by most people. Taku aroha mutunga kore ki a ia.

Division is a tool of colonisation ... justice for Ihumātao is justice for us all.

And so, if that’s how I feel, I also have a duty to stand in solidarity with other mana whenua struggles. Division is a tool of colonisation. We have our own tikanga to guide us. But justice for Ihumātao is justice for us all.

I am part of a network of indigenous youth, Māori and Pacific peoples. We are called Te Ara Whatu. We stand for climate justice and indigenous sovereignty.

Our rōpū ended up filling a role of creating media facilities, under the guidance of mana whenua and the six cousins. Creating a media tent, organising press conferences. Social media also became a biggie. Before I went up I was posting a lot of updates on our instagram. I think that became quite helpful for a lot of people.

The concept of a Keyboard Warrior is generally negative, and I don’t think social media works to settle arguments. But it is such a powerful tool for disseminating information. For having complete editorial control over our messages. There’s been so much online dialogue about Ihumātao, and so it’s almost just as important to stand in solidarity online as it is in real life on the whenua. I saw so many well-known Māori people on the whenua. Influencers and musicians. People like Melodownz, Poetik and IlBaz were there all weekend and genuinely there for the kaupapa. But Pākehā haven’t come to the table. There are very few who are willing to engage, especially those with big followings.

Ihumātao is a place of strong healing energy. I think it’s always important to give without expectation of return, but the manaakitanga of Ihumātao is straight up unreal, as I have experienced many times. I always leave Auckland drained, except for when I have been at Ihumātao. My heart lives in Te Urewera, but I also had the privilege of experiencing sunrise at Ihumātao. The privilege of being part of something we will remember in 50 years time. The mana whenua fed thousands of people for free in that first weekend. Within a couple days there was infrastructure for education, medical care, art school, kitchens. An entire city build from nothing but aroha and koha. Built on the peaceful principles of our ancestors. Being indigenous is so cool.