A Library is More Than Books: On the Proposed Closure of the Elam Fine Arts Library

The library does not simply house a collection – it enfolds a community.

The library does not simply house a collection – it enfolds a community.

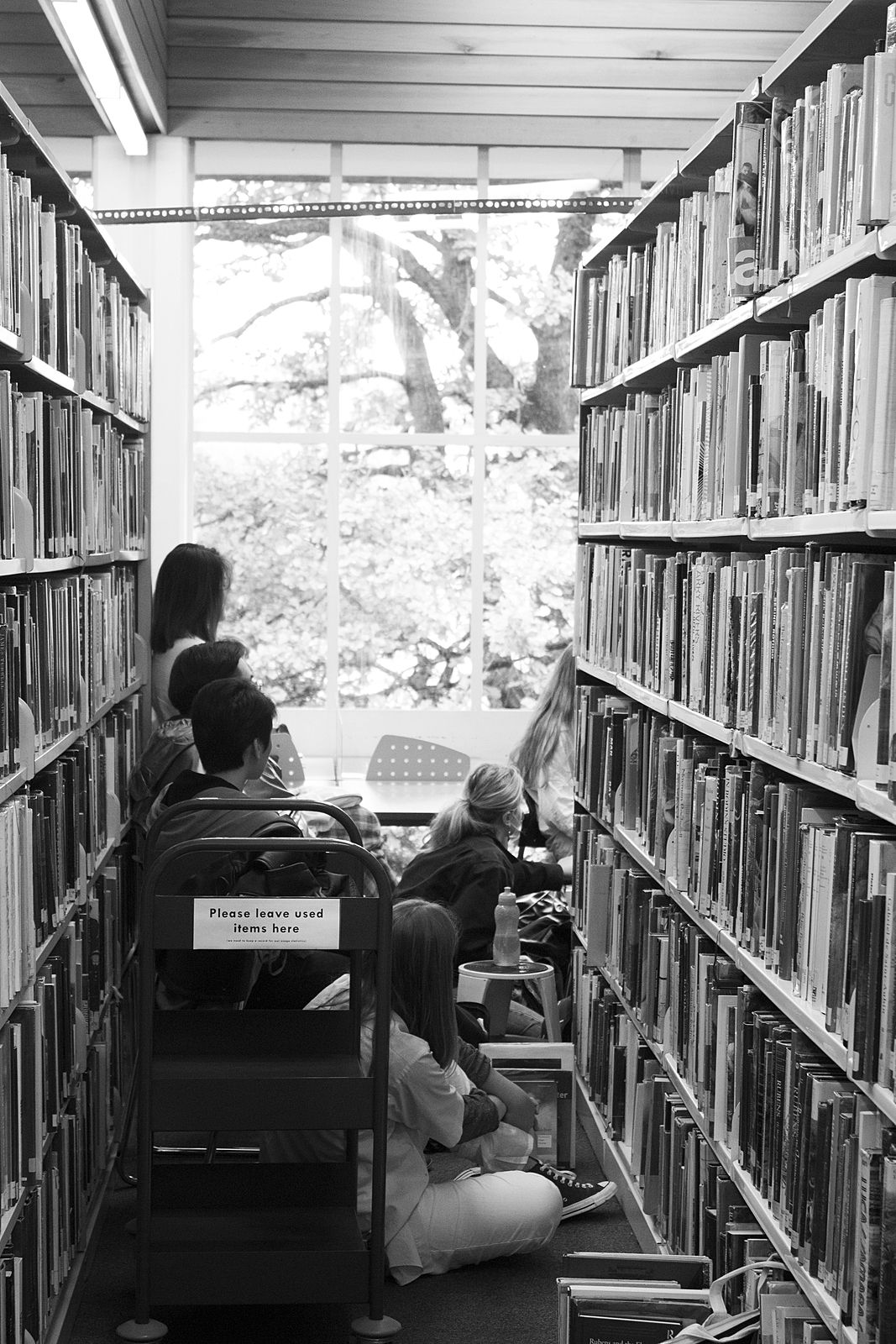

Nestled high in the trees, the University of Auckland Fine Arts Library is warm and leafy. Stepping in from the cold concrete of the Elam foyer, the atmosphere in here is different. It’s softer. Many make the pilgrimage to this refuge daily, it offers a retreat from staring at blu-tacked walls with a brain that refuses to cooperate. Far away from the panicked carnage of the Kate Edgar Commons, chip-dusted computers and darkly pungent Red Bull stains, the Fine Arts Library is the quiet embrace of an old friend.

It’s colourful in a way that art spaces with their white cubes and minimal edges fail to be. Beanbags line the floor and students fill the desks. Yellow shelves are stacked with bulging volumes. Each aisle boldly claims its terrain: Contemporary NZ Art, Sculpture and Painting, Journals and Ephemera. Trolleys are stacked high with spent research material and the allure of infinite possibilities. You can hear the sound of pages turning and quiet laughter. Grand glass windows overlook pōhutukawa foliage.

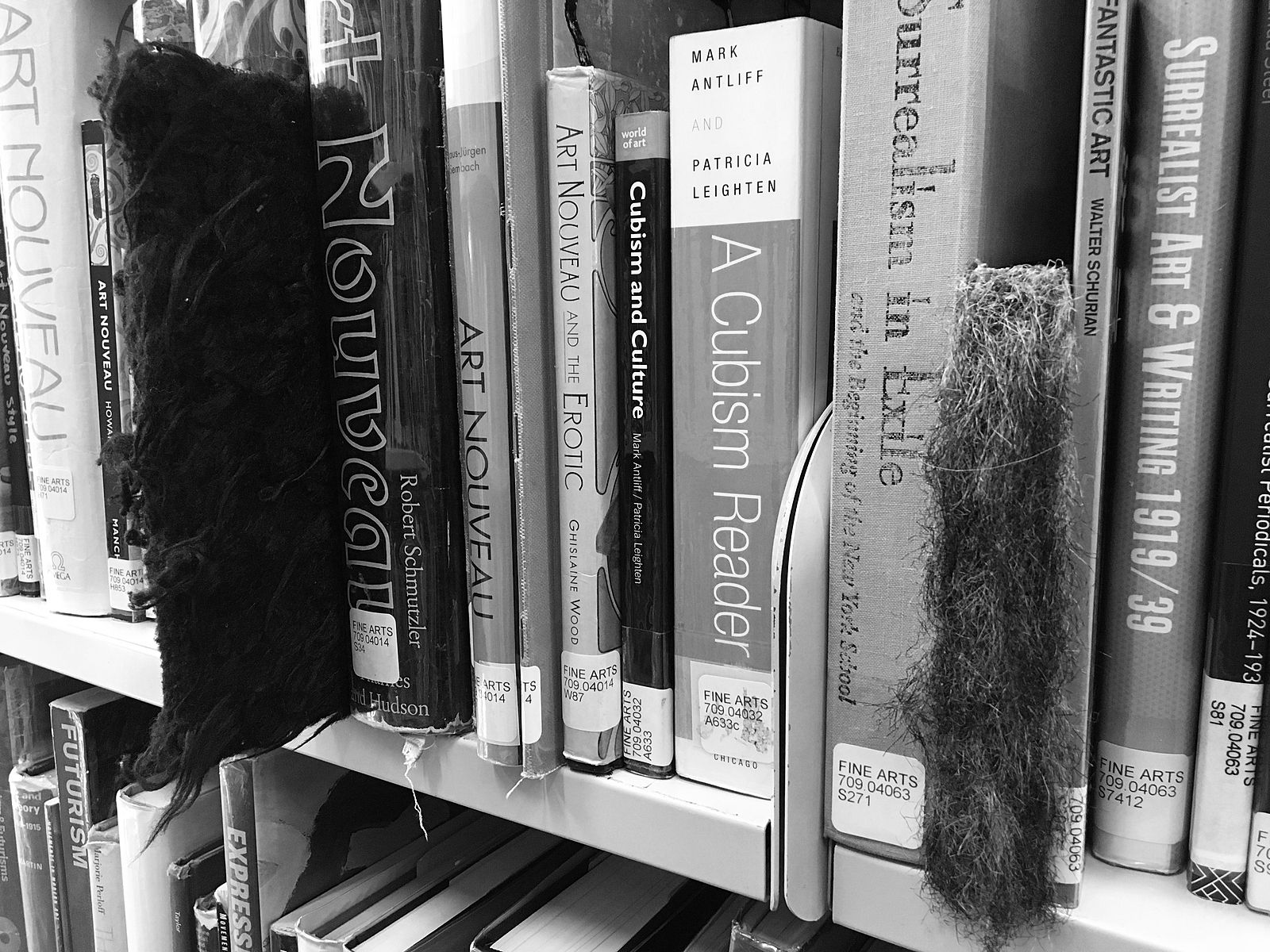

Opened in 1950, the Fine Arts Library has been the epicentre of art research in Tāmaki Makaurau – if not Aotearoa – for over 60 years. It houses one of the largest dedicated collections of fine arts material in the southern hemisphere. This collection is cared for by a staff of devoted and knowledgeable specialist librarians. It has informed art and art historical research for decades, throughout the country and internationally. It is the beating heart of the Elam School of Fine Arts.

Young researchers share desk space with some of the very artists, writers, critics and curators they study

Linked like a vein to the undergraduate studios, the Fine Arts Library is a student’s first point of entry into a wider art world. Here, they are given the globe as an open doorway. They are able to join century-spanning debates over form and content, to feel camaraderie with those who live oceans away, to speak with new friends while flicking through the latest edition of a magazine. Ephemera from student exhibitions bumps shoulders with catalogues from historical biennales. Young researchers share desk space with some of the very artists, writers, critics and curators they study.

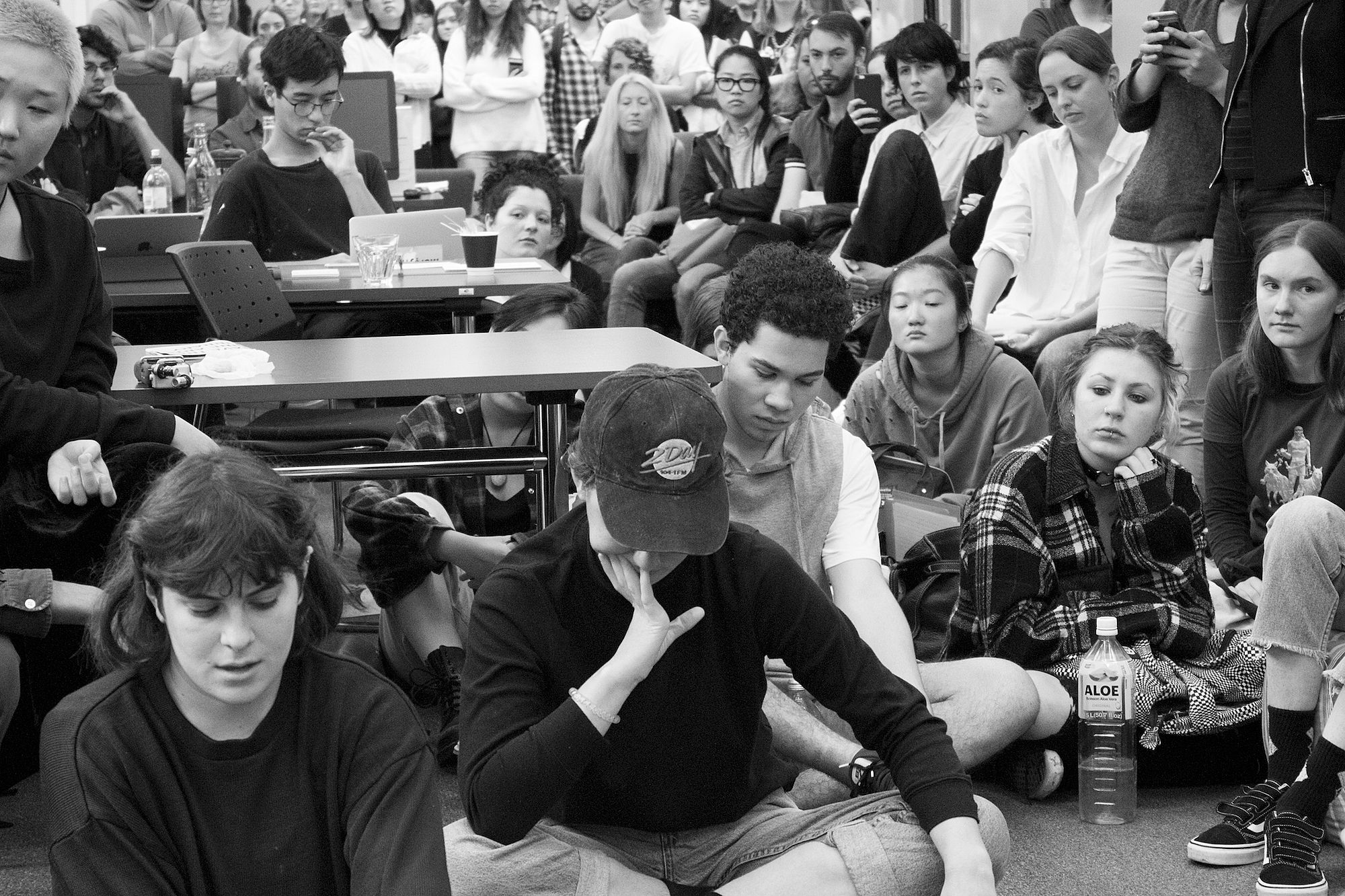

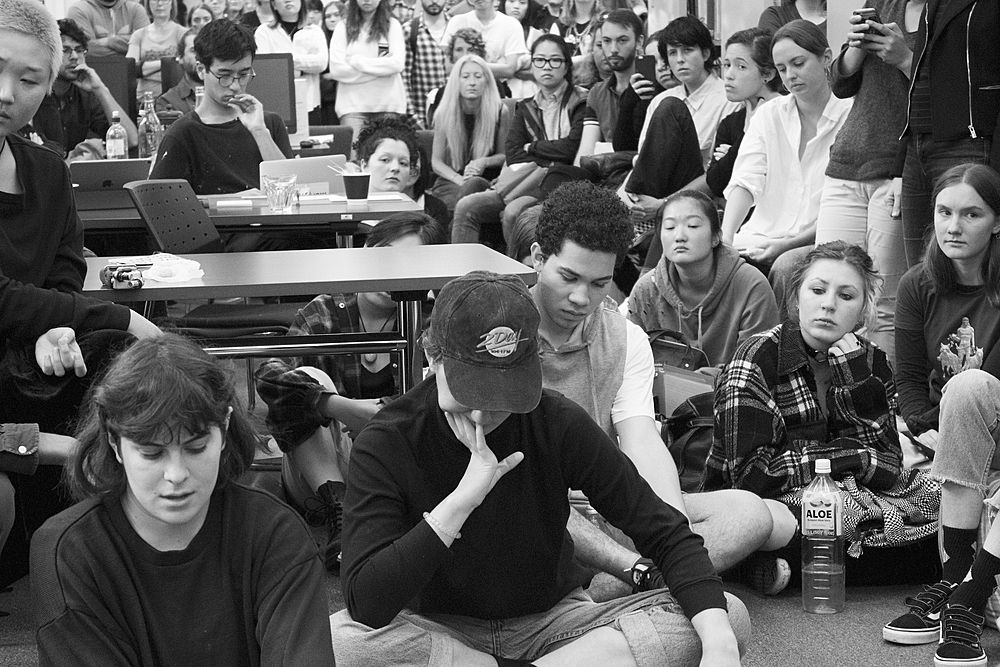

On 27 March 2018, The University of Auckland made public their plan to close this library, along with the other two specialist libraries that sit under the umbrella of Creative Arts and Industries – Architecture and Planning, and Music and Dance. This was announced in the CAI libraries review, a supplementary document to the wider, and equally scary, University of Auckland Library and Learning Service Review. At 81 pages, the review document makes for a grey reading experience. Inside, the argument as to how or why many decisions have been made is unclear. The reasons the CAI libraries are considered “no longer fit for purpose” include vague costs and claims such as “a steady decline in occupancy rates.” As their emphatic protest has demonstrated, the students who frequent and use these collections daily clearly feel otherwise – and might have said so, had they been consulted.

The proposal, as broken down here by the team campaigning to save the fine arts library, does not consider the way art students think or make. The use of poorly interpreted statistics to justify a broad-stroke conclusion about the next steps for this library fails to resonate with the people who actually use it. In response to the university’s vague claims of user decline, the Save the Fine Arts Library website has received over 800 responses in protest. Auckland University Students Association’s wider petition in support of all creative arts libraries has received 4000 signatures and written responses.

In the same way that science students need laboratories and technicians, art students need trained staff and specialist spaces

This is not the first example of a fine arts library at a university being placed under threat. Students from the University of Texas at Austin launched a successful campaign earlier this year when their own Fine Arts Library faced similar closure. They argued that “removing our library is an insult to our study and implies our research doesn’t matter.” The Save the Fine Arts Library campaigners at Auckland University agree wholeheartedly with both slogan and feeling. In the same way that science students need laboratories and technicians, art students need trained staff and specialist spaces. What a fine arts library does for its students is synthesise their research. It opens fundamental pathways for serendipitous connection, strengthening the links between tactile learning and making. Famed critic and semiotician Umberto Eco once wrote:

It is true that you often go to the library because you want a book whose title you know already, but the main function of the library, at least the function of the library at my house and the house of any friend we can go to visit, is to discover books whose existence we never suspected, and which nevertheless turn out to be extremely important to us.

This sentiment sits at the heart of arts-based research. It is in the space of a living fine arts library that artists and scholars may engender unique relationships to materials, that student makers come to understand the histories of their chosen crafts, and learn to frame their interdisciplinary interests within the contexts they have come to the university to study.

Research and making clasp hands so often within art. So much so that the Fine Arts Library acts as an extension of the Elam studios. For fluidity between art-making and research, it is vital there are dedicated research spaces linked physically to spaces of making. As noted by an architecture student concerned by their library’s proposed closure, one of the first lessons that the Architectural Design School at The University of Auckland teaches is that proximity is fundamental. Yet here is the same university proposing to move facilities further away from the very schools and students who use them.

Proposing to separate the collection, and to move the library away from where students make their art, demonstrates that the university does not understand the ways in which artists research – or perhaps they simply do not care

Of course, the university does not believe they are shutting down the Fine Arts Library so much as moving it to a different location. They intend to rehouse the collection within the General Library and offsite storage. This plan could not be carried out without the destruction of the collection through separation or dilution. The relocation of the Fine Arts Collection to the General Library supposedly engenders ‘interdisciplinary arts research’ for students. What they fail to understand is that artists do not need to be generalised to become multidisciplinary – they already are, by practice and by nature. Artists rely on chance encounters to open themselves to new ideas. To use offsite storage, as the university is proposing, you need to know which book you want to read. Proposing to separate the collection, and to move the library away from where students make their art, demonstrates that the university does not understand the ways in which artists research. Or perhaps they simply do not care.

Amidst outpourings of love, rage and despair, The University of Auckland has maintained its indifference to those who counter the set agenda. This is perhaps unsurprising given the way these spaces are seemingly viewed only in quantifiables: opening hours, patron transactions, shelf space. By their rationale, amalgamating the specialist libraries into the general collection and taking the lesser used books to offsite storage is not ‘closing’ a library, but simply moving furniture. What this logic fails to realise is that in removing these books, ephemera, scores, prints, journals and drawings away from their dedicated homes, you lose a collective identity that connects singular items to a much greater unity.

What they have vastly misjudged however, is that the root of a library is not its properties, but its people

The true measure of the Fine Arts Library is not as a catalogue. It is as a collection. This collection, like the community that uses it, manifests in the coming together of minds and materials. To the university, student grief at the loss of libraries is seen as ‘understandable,’ but ultimately temporary and inconsequential. What they have vastly misjudged however, is that the root of a library is not its properties, but its people.

The value of this space is most apparent in how it sustains the lives and practices of its attendant communities. It is the thousands of students, staff, alumni, artists, teachers, lecturers, curators, writers, researchers, historians and people it serves and houses. The people who have rallied behind the cause, because it is precious to them. They have exercised their right to protest, some putting their bodies forward to protect that which they value. You can find collective identity in the everyday gatherings, friendships and projects this space facilitates, the artworks it has inspired. If you look to the Fine Arts Collection you will find various documents and materials born in and out of the library. In the weeks since the closure proposal was announced students’ exhibitions, publications, protests and writings have all contributed to the community outcry against the proposed cuts.

The skills we have acquired in our education are precisely what make us so wary of the move to disestablish specialist creative arts libraries within the university

Central to the conversation, and those who have the most at stake, are the specialist fine arts librarians. They have welcomed and carefully documented much student ephemera into their collection: zines, photographs, posters, poetry and even final projects. Moreover, you can find the librarians at every student exhibition and graduate show. If we lose our librarians we lose the trained knowledge that goes into maintaining a collection as precious, unique and expansive as the Fine Arts Library. We risk losing support teams that know how to handle sensitive resources and who understand the ‘idiosyncrasies’ of art research – its laterality and unconvention, its reliance on physical spaces, browsing and human interaction. We lose attentive respect, love and care. Their loss will be felt keenly by students, whose anger at job cuts is as strong as that towards the threat to the collection itself.

We write this piece as activists. We write it as previous Elam students, collaborative artists and thinkers. At art school, we were taught to value the materiality of objects. We were taught to question systems, to push past the obvious and think critically. The skills we have acquired in our education are precisely what make us so wary of the move to disestablish specialist creative arts libraries within the university. We understand how necessary the arts are to livelihood, how valuable a critical education is and how dependent our people are to spaces of knowledge. We have felt the acute pain of losing access to resources. We have witnessed studios reduced to shoeboxes and seen the shrinking closure of art spaces across the country. This library is important. With 85% of New Zealanders participating in the arts, there is no excuse for the underfunding and cultural disregard of these spaces. The tremendous roar we have heard in the crusade to save this space has illustrated how vital and necessary our specialist arts resources are. The Fine Arts Library is a critical space for gathering, thinking and sharing. It is a place to be yourself and a place to be part of something more.

*

The following are memories sourced near and far from those who have loved and appreciated the Elam Fine Arts Library. Submit to Save the Fine Arts Library today to have your say, or send your recollections to [email protected] to continue adding to the list below. We are hoping that the active rallying against the university’s decision to close the library means that this piece will not come to serve as a eulogy.

My fondest memory was being dragged here on an early tour of the facilities. I felt terrified and challenged in a new school and city. I couldn’t understand the postmodern bent everyone was on, or why my lecturers kept going off about research bibliographies. When we came to the library, I picked some books off a shelf at random and grumbled my way to a slouching beanbag in the corner. It took me finally looking up from my seat to realise that hours had passed without my noticing. I keenly missed the magic of this space once I moved to a different institution, one without a dedicated research space. The library is a safety net you can wait the weather out in, absorbed in reading. When you feel most alone, you find other makers to belong with here, from the dust motes of history. – Vanessa Crofskey

The first thing I ever made that felt like a real piece of art to me was a little zine that a friend and I put together. We first thought it was just a fun experiment, something collaborative where our friends could stick old poems, publicise their shows and exorcise angry essays. Then one of the librarians asked us for a copy for the collection. And just like that, our project seemed to become part of a longer history where ‘fun experiments’ could actually also be valuable and interesting pieces of art. Of course, perhaps our funny little zine always had been part of this bigger picture, but it was the kind and genuine interest from the librarians in what we were making that allowed us to see that. I love the library and the communities that congregate there. I displayed my final Honours work for Elam in the library, and I still come there to study and think, even though my history classes are now much further away. It’s not just the books, but the care of the librarians and the sense of belonging that makes it a truly special place. – Rachel Ashby

1988 was my first year at University. Elam of that time was essentially a library with an art school attached. I became a daily, probably often many times daily, user. Looking back at those first four years of immersion, I am envious of the freedom and luxurious acres of time I had to traverse this incredible archive. The thrill of making connections that were formed there has been basic to everything I have done since. I despair at the current university administration’s destructive plan and its unwillingness to recognise that a university is only as good as its libraries. – Anna Miles

It is only when cloistered in carrel number four of the Fine Arts Library that I can get any work done. With the door closed, the light is diffused and there is a very special kind of quiet. All I need to do is open the door and step between the shelves to access the 759 section on artists, the large books, the historical periodicals, the 700ish section on art writing. If I need a break I flop onto an armchair and finger through issues of Mousse and Texte zur Kunst. It is in carrel number four that I have planned courses in art history, prepared lectures and tutorials, written articles and theses and before that studied for tests and exams. There is no doubt, for me, that it is the very centre of the universe. – Victoria Wynne Jones

As someone who had my art school and postgraduate experiences in the South Island, my relationship with the Elam Library is one of distance. I studied in an institution that was grappling with the loss of its own fine arts library, which was gutted and centralised. I feel very invested in and emotional about the future of the Elam Library as it represents so much of what I see as the value of arts education, research and community. As a postgraduate student based in Ōtautahi, I regularly inter-loaned publications from the Elam Library as I couldn't access these resources through my own institution. As I was researching specifically around the subject of artist's books and art publishing cultures, I would not have been able to complete my Masters research without the specialist collections in the Fine Arts Library. – Sophie Davis

In 2015 I spent a month using the Elam Fine Arts Library to aid my research in writing a manifesto, which in turn informed the better part of my practice for the last three years and my methodology for working with artists. During this time my research was assisted by the incredibly knowledgeable staff of librarians. I have a special soft spot for their collection of exhibition ephemera and short publications, which are taonga, and were vital and necessary to my research then and now. Although I never went to Elam or The University of Auckland, knowing this library exists as an aid to an entire community, even just to do some quiet reading, is how I think always of the library. It’s a precious place and resource. – Hana Pera Aoake / Fresh and Fruity

Fresh and Fruity are currently working on a project that attempts to record Māori practitioners and protect their practice from erasure by history's colonial lense. The Elam Fine Arts Library's ephemera collections of exhibition catalogues and publications has been fundamental to my research into under-recognised Māori artists. Libraries and archives are the kaitiaki of our collective knowledge.Libraries need adequate staffing to maintain collections and keep them accessible. These archives are already hard enough to access; this is one of the only archives of its type and size in the country, and it needs its own space away from general collections, with dedicated librarians. Without access to these or adequate care we will lose entire artist's histories and vital research resources. – Mya Morrison-Middleton / Fresh and Fruity

I remember it as leafy, and it was. The Elam Library was a safe haven, shrouded by trees, it's not just where you go to get information, it's where you go to get ideas. Libraries and reading are filled with reverie and it’s that reverie that is so essential to creation – ending up somewhere off the map, in a book next to the book you thought you were looking for. The Elam Library is the heart of the school, to me it’s my fondest memory of Elam. The library more so than anywhere else was a studio, and perhaps that makes sense as I have ended up a writer, rather than an artist. Even so. I spent a lot of time as a student drifting there, looking out the window to the traffic, barely glimpsed through the trees in the ravine, Grafton Bridge invisible to the eye but close, losing myself in a book, then snapping back into focus. Those moments matter! I don't have a special moment of profundity or transformation in the Elam Library – it was more just a place that was a constant, an epicentre for thinking about art – especially New Zealand art – and also sitting somewhere warm and dry as a lowly student. The tutors who would enthusiastically send you on a wild chase, 'Go now and look it up in the library!' Late last year I published my first book, Tinderbox, which is a book about a book, and specifically about Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. In Bradbury's sci-fi classic firemen burn books instead of putting fires out. Bradbury said, “Without libraries what have we? We have no past and we have no future.” If you take away the Elam Library you take away the past and future of the school. What's left? – Megan Dunn

In 2012, Claire Bishop penned her notorious Digital Divide essay. Her main argument held that while many artists were using new technologies for creation, circulation and consumption, very few were reflecting “deeply on how we experience, and are altered by, the digitisation of our existence.” I first read this piece in an issue of Artforum plucked from a shelf in the Fine Arts Library (it had a butter-yellow Lawrence Weiner cover). It turned out to be seminal for me, sparking an interest in the relations between art and networked technology that would flow into my Masters thesis years later (now also housed in the library, incidentally with a yellow cover of its own). Would I ever have stumbled upon this essay online? Perhaps, but what of a thousand other serendipitous encounters I might never have had were it not for this library? The thing about conducting research through digital systems is that there is so much less opportunity for chance, romance and relations to come into play. Online library catalogues work based on algorithms that prioritise only the most popular titles, promoting these more insistently to browsing eyes. You won’t spot an intriguing title two shelves down, you won’t stumble on a slim volume irrelevant to your current research but integral to everything you’ll ever think or make from that day forth. Around the world, archives and collections are being increasingly supported, their ongoing relevance confirmed through digitisation alongside enhanced physical care and accessibility. This parochial move by the university reveals exactly what is at stake when our existence is reimagined by systems, when all feeling is removed from the equation, when our world is made to 'work better' but not necessarily for us. – Lucinda Bennett

On reflection it sounds almost comical, but at intermediate school our teacher gave us the Herculean task of determining what form of art we believed to be most worthy. No biggie, I was convinced of my answer: Architecture. This is what led me, accompanied by my mother, to the Architecture and Planning Library, age eleven. I recall poring over images of Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp, and I know that it was in this purpose-built architecture library that my lifelong fascination with the built environment was crystallised. It is not a surprise that I eventually became a student in the School of Architecture and Planning, frequenting the library, where I was energised by the limitless potential of the holdings, and recognised the library’s function as the heart of the school. I know that my experience of the library is not unique, and I wholeheartedly hope that all libraries within the Creative Arts and Industries faculty remain open to provide intellectual and cultural sustenance for all of us. – Sebastian Clarke

I am outraged to hear that The University of Auckland intends to close the Fine Arts Library. Universities have a responsibility to foster specialist, focused research, thinking, publishing and making. The loss of this focused research library (or any other specialist library for that matter) as a means to cost-save is totally unacceptable and short-sighted and I am absolutely opposed to this move. The Fine Arts Library is the jewel in the crown of Elam – its heart, brain and memory – it is the school's singular consistent feature and without it, The University of Auckland undermines the needs of its students, faculty and the wider community. I urge the Vice-Chancellor to protect such precious resources as a specialist library – a resource that would be irrevocably lost if dismantled and centralised. – Dane Mitchell

I wrote my first art history essays in the Elam Library. Surrounded by books on art it was a touchstone for something that I might like to do: maybe I’d work in the arts. Throughout my thesis I accessed it for visual references, and the books in that collection helped shape my art practice. The library is a place of possibilities, a place to imagine, gather and stir. These are the things that artists need – an encounter with material culture. – Nova Paul

A few years ago I was incensed by a sexist remark made by Georg Baselitz that “women don’t paint very well.” Baffled that assertions like these still persist, I began physically searching the Fine Arts library's collections of DVDs, art journals and artist monographs, and compiled a substantial list of outstanding female painters to present to my students. To name just a few, I found a documentary on the life and work of single mother and artist Alice Neel, I read essays on Lee Lozano’s various withdrawal strategies, and I pored over plates depicting Joan Mitchell and Agnes Martin’s paintings. I can confidently say that the majority of that slide talk was formed positioned on a blue 80s lounge-chair in a warm light-filled corner, or crouched on the floor between book stacks. – Anoushka Akel

A line I’ve shared often in my teaching at Elam is the artist Barbara Kruger’s: that dated magazines make great reading material for a student artist. It’s one way of making the point that in art, keeping up with what’s going on is less important – and possibly even unnecessary – compared to seeing past it. The most borrowed might be a good measure of what it is productive to have on hand for many fields, but the serendipituous research that can happen, distractedly, in the Fine Arts Library is all the more valuable when it is not rationalised by such logics of space-efficiency. The unfashionable, the forgotten and the discredited, need to be near the studio, not called up from stack. – Jonathan Bywater

Whoever decided to close down the Fine Arts Library has no idea how special and important this library is. The Elam Library needs to be at Elam! I got so much inspiration from the Fine Arts Library. From having all the art books in one place, having them in the environment where we make art, the inspirational feeling and atmosphere, and it is the only place that brings together all the individual fine arts students. I wrote many film scripts in the library, and still visit it 20 years later. In 1997 I asked an Elam student in the library if she wanted to act in one of my films. She said “maybe” and we have been making art together for the last 18 years. Next year, will we have to fight against Albert Park being turned into a car park? I won't be surprised. Please stop wasting our time and let the Fine Arts Library remain for many more generations to benefit from. – Florian Habicht, 1998 Elam Graduate. Director of films Kaikohe Demolition, Land of the Long White Cloud, Pulp: a Film about Life, Death & Supermarkets, Spookers, Rubbings from a Live Man and Woodenhead.

The Fine Arts Library was a critically important resource for me during my six years of full time study at the University of Auckland. While my study was evenly spread between the Fine Arts and Art History departments, we were particularly aware within the Elam programme that the library was the envy of comparable art schools in the southern hemisphere, both for its extensive resources and its specialist staff. Learning to be proficient in navigating its wealth of books, journals and archives – located in close proximity to the studios – was a high priority in the early stages of commencing study at Elam. And rightly so. Because if what an art school aims to do, first and foremost, is to enable students to build their capacity to generate self-initiated research, since its conception the Fine Arts Library has been a key catalyst to these aspirations. This grounding has carried me a long way in my subsequent career in the art field. – Stephen Cleland

If you could earn Frequent Flyer points at the Fine Arts Library, I like to think that I might have earned Gold status (maybe even Elite?) over the past 12 years. Imagine my joy when they put a branch line onto the cycle path so I could whiz down from Grafton Road and park my bike right outside. I could be typing away in my office, have to stop because I needed to check something, and then be poking about in the library’s laden shelves in an instant. It’s like a club rooms where everything engages you – not just what is on the shelves but the staff, the art on display, the notices pinned up on the noticeboards, the fellow library users. “Sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name and they’re always glad you came” as the lyric goes. I have tried to be of some use to the library itself as well. I remember receiving a summons from Jane Wild to identify some unnamed early student watercolours in the archive upstairs. They were placed before me by white gloved hands – a bit like an unseen Latin translation – and I managed to identify a profile portrait of Samuel Clemens on his 1895 tour of New Zealand. At last a use for my strangely sticky visual memory! Another time I was the guinea pig for the new INZART database, in awe of the subject librarian who had laboured to get the full text of obscure newspaper reviews from the ephemera files fully searchable. But it is impossible to leave the Fine Arts Library without being snagged by the 'Recent Journals and New Books' corner with its lovely window-lit lounge chairs and coffee table which encourage you to linger over the latest publications. How could this atmosphere ever be re-created elsewhere? – Linda Tyler