My Father Made Me a Bure

Artistic director and co-founder of theatre company The Conch, Nina Nawalowalo, shares the legacy of weaving her own bure.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

When I was a child, my father, Ratu Noa Nawalowalo, made me a Fijian bure.

He built the timbers and floor from offcuts from my mother’s woodwork class and wove the roof from strands of pandanus and string. Every Christmas my Fijian bure became the stable for Joseph, Mary and the baby Jesus to shelter in by the Christmas tree. At other times of the year it became a home for dolls. With its open front and back wall made of masi, it became a tiny theatre where I told stories to my younger sister Bridget.

A house within the house.

A world within the world.

Our home was the same.

Having a Fijian father and an English mother was unusual for both sides in the 1960s.

My father had come to Wellington in the late 1950s to attend Victoria University. He flatted with Albert Wendt, Filipe Ubole and Tomasi Vuitelovoni up the end of the Wellington cable car road. My Ratu came to read law at Victoria University, becoming the first Fijian barrister and solicitor in New Zealand. My mother came as a young English nurse from her home in Oxford. Full of a sense of adventure and idealism, she flatted with a young aspiring Dutch photographer, Ans Westra. My father and mother met at the Wellington Chess Club, fell in love, and married, all captured in black and white by Ans Westra.

Our house spoke of this meeting, populated as it was by English ornaments and Fijian mats, tabua, masi and kava bowls.

Pacific people coming and going alongside Ans, friends who had shared the cabin on the boat from England, Fijian men and their families – the Tuitubou family, the Tupu family. My father taught English families how to dig a lovo in the back garden. My mother brought in pots of tea for Fijian scrub cutters and other Pacific people who came to the house with their immigration papers.

The Dawn Raids raged.

My Ratu represented Pacific people in the Wellington court, and won a historic case that led to a change in the law. Fought the good fight alongside Lani Tupu Snr, setting up with others the first Pacific Advisory Committee, in Willis Street, and the Newtown Community Centre.

By the early 80s it was still raging, now with the Springbok Tour.

My father sent me and my brother Robert back to his village, Tavuki, in Kadavu.

My mother encouraged me towards Wellington Teachers College, to get a job. Meanwhile, I moved onto the basketball court, beginning under the two great coaches, Hori Thompson at Wellington East Girls’ College and American Bill Eldred, who coached the Wellington team. Newtown basketball stadium became my home away from home. In that world within the world, players from every background united in intense playfulness. There was Magic in Johnson and poetry in the motion of a layup. The rigid squares of division outside became the curved line of the D – I loved the freedom to move. The court was a board on which to play the game, the Newtown basketball stadium was my home. There were skills to conquer; the purpose — to play the game.

There were skills to conquer; the purpose — to play the game.

I listened to my mother, and at Wellington Teacher’s College I met Englishman Robert Bennett, who introduced me to white-faced mime. I loved the poetry of mime and moved house, from the court to the stage, whose boards became the place to play the game, the theatre became my home away from home.

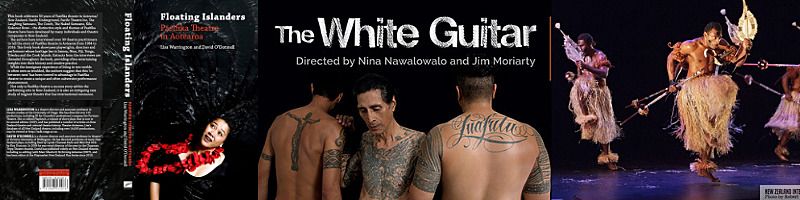

Left: Fiona Collins from Vula on the cover of Floating Islanders (David O’Donnell), Centre: The White Guitar, Right: MASI, Sydney Festival 2013. Directed by Nina Nawalowalo and Tom McCrory -The Conch, NZIAF 2012.

At the instigation of Robert Bennett, Fergus and I separated from the New Zealand delegation and travelled to Poland, where we were hosted by the great Olsztyn Deaf Pantomime and artistic director Bohdan Gluszczak. Fergus and I performed New Zealand Mime International work in Polish villages. From there we travelled to London where, after much teaching, I could afford to continue studying mime and theatre with Desmond Jones, Philippe Gaulier and Pierre Byland.

There was something so familiar in my mother’s country that I felt at home, and was embraced by North London Afro-Caribbean women to join their basketball team. I travelled to Italy in 1987, supported by the New Zealand Arts Council, to study commedia dell’arte.

In each world I learnt, moving from one to another. Through mime I was drawn into the world of magic and illusion. Here there were magical skills to be learnt and the poetry of illusion. The stage of close-up magic became my home for seven years, from the London International Mime Festival to The Magic Castle, Los Angeles.

In 1994 I travelled back to Kadavu, Fiji, with my father for the last time. Here in the village a profound shift took place in my heart.

I stepped into the bure itself.

Here the boards sat on the vanua, spirituality took the place of magic, and poetry was in the oratory of the chiefs as they spoke to my father.

One day I stood by the sea and listened to the women singing hymns to one another as they waded into the lagoon to fish. This was the language of my soul. Returning to London, I felt this change profoundly. I had been gifted tremendous experience, I had been sheltered by the home of European theatre, but this was not my bure.

In 1997, when my father became very unwell, I travelled back to Aotearoa. When he passed away, there, sitting in our family home, was my childhood bure. With the hands that had built it gone, I knew that it was time to build my own.

Though I had studied mime and theatre, and worked in magic, on coming home in 1997 I went back to the gym. Basketball gives us a space to express our beauty, grace, agility and power, to be poetry in motion, to push, move, sweat and shout without getting arrested. To find our flow in the face of obstacles, to express ourselves.

Basketball sits at the crossroads of culture, politics, music and dance, and style. Always style.

In the gym I saw the intersection of the game, Māori and Pasifika culture and hip hop. DLT had just dropped his first solo album, The True School, Wellington DJ Raw had just won the world championships, and Fiso Siloata and Footsouljahs were spitting rhymes and shooting hoops.

I wanted to capture the energy I saw in the gym on the stage. And so we created our first piece, Swish, in 1997. Starring Fiso Siloata, Vela Manusaute, Kirk Torrance, Ione, Nga, and a young, unknown, 6’ 4” South Auckland man who had the height to play a centre. The piece brought these worlds together through basketball, a live DJ on stage, rap, cultural movement, the story of coming together as a team and overcoming obstacles, and the nail-biting finale brought packed houses to their feet nightly as the outcome of the play came down to an actual free throw on the line.

In the fire of this production I forged some of the core values that informed the architecture of my house.

Though my art form is theatre, my mindset is always basketball. They may seem worlds apart, but there is a key factor that unites them – performance.

My houses were both alike in dignity.

Whether you’re stepping onto the court or the stage, you’re stepping up to a moment of truth. It’s time to deliver.

All the rehearsal, all the training.

Whether it’s the running of careful choreography or an offensive play, it all has to come together in the moment of performance. Whether you’re on the court, or on the stage, the game reveals you. How much you can walk the walk. What you know and what you have yet to learn. How creative you can be when things don’t go to plan, and how you handle pressure.

You can’t hide in the game. No matter how much you daydream, there is such a thing as reality. And this is a gift. Because if you choose not to hide in the shadows, if you let the light of that reality shine on you, you learn. Whether we’re in the theatre or on the court, we come together to play. All the world’s a stage, said Shakespeare, and we are merely players. If he’d have been a b’baller he might have said all the world’s a court and we are still merely players. Each has a part, each has a position, but the glue, the superglue that makes us stick together, is playing the game. That sense of intense playfulness, the joy of participation, even under a barrage of trash. Playfulness is creativity in action.

“What would you do if your life came down to a free throw on the line – would you take it?”

So the key is the moment of performance. To quote a line from Swish, “What would you do if your life came down to a free throw on the line – would you take it?”

In 2002, I formed The Conch with my husband Tom McCrory. My first production, Vula, set in 1400 litres of water, was inspired by that moment eight years before, seeing the women singing in the lagoon. Created with the legendary Fiona Collins, Tausili Mose, Susana Lei‘ataua, Kasaya Manulevu and Salesi Le‘ota. It went on to tour for six years internationally, including in the South Pacific Arts Festival in Palau, Guam, Fiji, the Sydney Opera House, six cities in The Netherlands, Adelaide, Brisbane and London’s Barbican Centre.

Alongside this core strand there are many productions I have been blessed to work on, along with this country’s amazing artists, from Hone Kouka’s play The Prophet, which premiered at the New Zealand International Arts Festival under the leadership of Carla van Zon, to directing Peter Wilson in Duck, Death and the Tulip, winner of an Outstanding Theatre Award at the Edinburgh Festival 2014, for his company Little Dog Barking. I’ve always been drawn to work that weaves strands together, like the string and pandanus of my father’s bure. So much learning comes from these moments of intercultural weaving of stories together. These stories have strengthened my house.

The Prophet written by Hone Kouka, directed by Nina Nawalowalo, actor - Miriama McDowell, NZIAF 2004.

The White Guitar was an incredible interweaving, born of the meeting of my husband Tom McCrory with Matthias Luafutu at the New Zealand Drama School. Matthias’s gift on leaving was his father’s book – A Boy Called Broke, inspired in a prison library as Fa‘amoana Luafutu read Albert Wendt’s book Sons for the Return Home. Fa‘amoana wrote to Albert from prison, and Albert replied and encouraged him to write his story. How unbelievable for me to come full circle. These interweaving threads of story across space and time. From these incredible men arriving in the late 1950s to a rehearsal room working paepae with Tom McCrory and Jim Moriarty. Interweaving created The White Guitar with Matthias; Malo Luafutu, aka Scribe; their father, Fa‘amoana Luafutu; and Tupe Lualua in her unforgettable role as the grandmother.

To be trusted to share this story, described as “a seminal moment in New Zealand theatre history”, throughout this country was an utter privilege. How remarkable that Albert Wendt and Fa‘amoana Luafutu met again in the auditorium of Q Theatre, Auckland, as Albert stood and saluted him.

Now, almost 20 years and nine productions on, my bure stands stronger than ever. It has withstood the cyclones of success and failure because of the bindings of Kaupapa Pasifika Vaka Viti. Its poles are sunk deep in the vanua, we are supported by the boards of vakaturanga, we enrich the mana of those who enter, and the space itself is tabu. Within my bure my worlds meet – poetry, magic, the breath of spirit and play, Pacific and European.

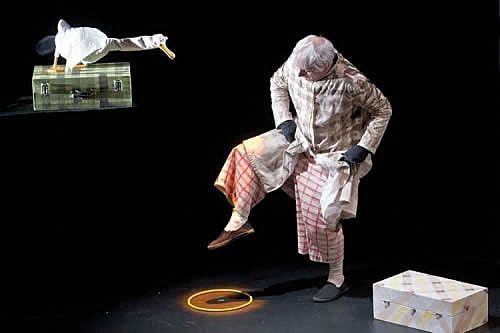

Duck, Death and the Tulip. Directed by Nina Nawalowalo, Edinburgh Festival 2014, (Peter Wilson - Little Dog Barking Theatre company).

My father wove my bure from the materials he had to hand – wood, masi, string, pandanus and childhood memories of the bure in the village he left behind. I have woven my bure from the experiences of my life, the materials to hand. Now, at 58, I am at home in myself, my body is my bure and all the world is the stage. All the world is a court and it’s about how we play the game. The truth is we do win. But that moment passes and we’re faced with the next game. The truth is when we win we can lose our humility. The truth is the ego can defeat our gratitude. The fact is we do lose, but it’s how we deal with loss. How we go back to the drawing board and learn from our shortcomings. How we maintain our dignity. How we forgive ourselves and others. How we stay out of the blame game. How we remain generous to those who teach us the hard lessons of defeat.

As a great teacher once said: There are no friends, there are no enemies, there are only teachers.

Every one of us here is in the midst of the game. Weaving their own bure.

Stay playful.

Stay creative.

Learn, and you can’t lose.

But always step up to the line.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photo by Pati Solomona Tyrell.