My Florian Habit

Jacob Powell on the infectious and electric Florian Habicht, the films and the maker.

Jacob Powell on the infectious and electric Florian Habicht, the films and the maker.

I first happened upon the name ‘Florian Habicht’ ten years ago, whilst working at the University of Auckland Elam School of Fine Arts library; the very same Elam school of Fine Arts where the filmmaker spent a good portion of the 90s as an undergraduate photography major.

I was going through our audiovisual collection one morning when a nicely designed DVD cover caught my eye. It was Habicht’s first feature Woodenhead (2003); critically lauded in Aotearoa as a triumph in terms of its creative approach to filmmaking. I later heard of his 2004 follow-up Kaikohe Demolition from a colleague who grew up near Kaikohe and knew some of the interviewees. An altogether different affair, Kaikohe Demolition documents colourful locals in a documentary about demolition derbies in far flung Northland. But it wasn’t until a wintry afternoon in July 2008 that I finally viewed a Florian Habicht film.

I attended the New Zealand International Film Festival screening of Rubbings From a Live Man – a documentary-cum-memoir about the life of prolific New Zealand thespian Warwick Broadhead – at Skycity Theatre. I was immediately struck by Habicht’s willingness to play with the concept of ‘reality’ in a documentary format. This was followed by a Q+A session which saw the director interviewing a brilliantly combative Broadhead. A perfect introduction to a filmmaker and his or her work!

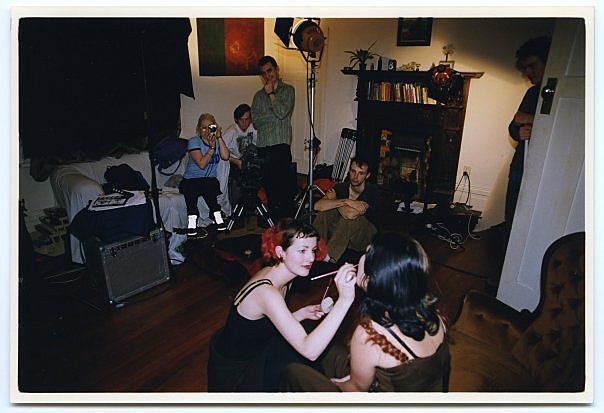

In Rubbings, Broadhead effectively narrates his own life story using the tools of his trade: rendering significant chapters of his life as theatrical spectacles. This narrative stratagem is reminiscent of actress and director, Sarah Polley, whose father narrated his own memoirs which acted as a framing device for her skeletons-in-the-closet family history, Stories We Tell (2012). Habicht lets the production process bleed in around the edges. Crew members, helping set up shots, are purposefully filmed and left in the edit, leaving no doubt as to the constructedness of the venture. Habicht’s Love Story would later continue this constant breaking-of-the-fourth-wall.

Structural porousness has become central to Habicht’s modus operandi as a filmmaker. On my recent viewing (only last month) of Woodenhead I was most reminded of Rubbings, especially in terms of a consistent layering of surrealism and a certain kind of ‘theatricality’ present in each. More than any of his subsequent documentary work, Woodenhead is, in many aspects, very much an art-school film. The whole production is about subverting – or perhaps perverting – known cinema and storytelling forms. Habicht takes the conceit of a classic Grimm-style fairytale but executes the simple narrative as an exercise in surrealism. He contrasts almost child-like characterisation with casually adult onscreen action.

On a technical level, Woodenhead defies expected filmmaking norms by having the entirety of its audio – dialogue, music, and a surfeit of overt foley effects – recorded before the actual filming. The visual component was shot later with a completely different set of actors and the filmmakers make a point of purposefully mismatching the audio and visual facets of the film. The cult status of Woodenhead does not surprise me at all. It is a gripping and surprisingly accessible surrealist work, shades of which continue to be seen in Habicht’s deft blending of documentary and narrative forms. So naturally, my hand shot up immediately to cover Love Story for The Lumière Reader.

I was immediately struck by Habicht’s willingness to play with the concept of ‘reality’ in a documentary format.

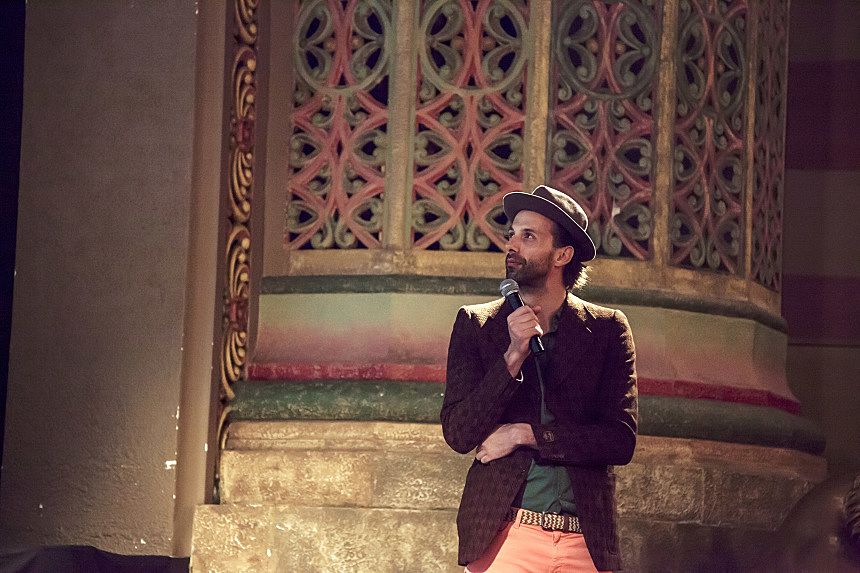

In 2009 Habicht travelled to New York City as the inaugural recipient of the Harriet Friedlander New York Residency. His stay resulted in the conception and production of documentary-fiction feature Love Story, which had its world premiere in Auckland’s Civic Theatre to open the 43rd New Zealand International Film Festival in July 2011.

Hitting the streets with his tiny crew and a single actress – Masha Yakovenko, an acting student at the time, agreed to be cast in this strange film by the unknown foreign filmmaker – Habicht’s Story was primarily sourced from the willing residents of the city, and whose interactions provide the backbone of the film. Love Story’s title refers as much to the love of these people for their city as it does to the ‘romance’ being played out between Masha and Florian.

I was there in the Civic that premiere, along with more than 2000 others, including Habicht and several other key members of the crew. The filmmaker has an infectious energy that radiates out from him and is imbued in his films. The atmosphere was electric. This is an aspect of the filmmaker that has consistently struck me: Florian always brings a genuine sense of curiosity and wonder with him and despite his artful, often odd points of view, there is never any sense of pretense. He achieves levels of intimacy comparable to American documentarian Errol Morris, despite a marked difference in their demeanor and approach. Habicht’s natural openness is subsequently mirrored back by those who find themselves in front of his camera, as he draws even the seemingly reticent into conversation.

The filmmaker has an infectious energy that radiates out from him and is imbued in his films.

I take it this is a large part of the reason iconic Brit-Pop band Pulp (and in particular lead singer-songwriter Jarvis Cocker) agreed to have Habicht make a documentary about them. Pulp: a Film about Life, Death & Supermarkets, which is the only official film about the band to date. The film shows great affection for its famous subjects as well as the ‘common people’ of Sheffield, as each provides commentary for the other. Florian has a very natural and uncritical way of presenting people as they are. In Jarvis Cocker’s case we see footage of an aging rocker who can barely change a car tyre (yes, Habicht shoots him doing it) and whose concert supplies include a large suitcase of prescribed medications and natural remedies. He seems to swing between displays of healthy self confidence and being carried away by minor neuroses. But just as the camera has all but stripped away our sense of Cocker’s celebrity, the Pulp vocalist is transformed under bright concert lights. He cavorts across the stage with the wild abandon and energy of a man half his age. It is truly a kind of inexplicable transformation.

Jarvis Cocker really is a star. I am no Pulp devotee, nor have I ever been, but I fucking love this film and I now find myself with a soft spot for both Jarvis Cocker and Sheffield. This is the magic of Habicht’s ability to expose what is fascinating in the seemingly mundane, connecting the personal with the extraordinary. Compare Pulp’s rendering of a ‘down-to-earth superstar’ with the poetic moments of philosophy the filmmaker unearths amongst laid-back locals in a remote mineral hot-pool in Kaikohe Demolition or unassuming weekend-fishers on a Northland beach in Land of the Long White Cloud.

The nature of Spookers the ‘haunted attraction’ and subject of Habicht’s latest film – of the same name – embodies this kind of ‘extraordinary everyday’. In this case a scare-park housed in one of Auckland’s former psychiatric hospitals, with a reputation (in some quarters) for being among the most haunted locations in the country.

My own (albeit distant) connection to Kingseat Hospital (as it was formerly known) is via a friend who did a mental health nursing practicum there. He tells of an experience where one day a seemingly placid patient came outside to a table where other patients were busy doing craft projects. Without warning, he took a hammer, dropped his trousers and nailed his penis to the table. Spookers the place and the film, plays up to this kind of sensationalist, horrific imagery, which provides the backbone of their scare experience.

Habicht cuts interviews with the park’s unlikely, non-horror fan owners Beth and Andy, who display a high level of care and concern for their staff and customers, against interviews with former staff and patients of the institution. One interviewee was a patient at Kingseat for almost 20 years and now works in the Psychology department at the University of Auckland. However, the bulk of the screen time is taken by the actors who inhabit the gore and terror central to Spookers. The question of whether this commercial venture disrespects the histories housed within its facilities, or trades on the propagation of unhelpful mental health tropes, is never far from mind.

Though most are on the fence about this aspect of the scare-house experience, what slowly builds is a picture of the park as both a community and as a form of ‘treatment’ for its staff, many of whom are facing very real struggles in their own lives: be it depression, identity issues, or family troubles. Once again Habicht creates an atmosphere of trust and openness which produces a documentary of intimate personal exploration within a context of extreme artifice.

Florian Habicht’s career is one I’m locked into for the long haul.

Spookers is kept from becoming mired in solemnity by regular injections of humour and beautifully staged, offbeat cinematic moments, such as the staff, in full make-up performing some kind of dance routine or playing a casual game of rugby. Many of these moments call back to the highly theatrical recreations Habicht and Broadhead produced for Rubbings almost a decade before.

Florian Habicht’s career is one I’m locked into for the long haul. Few filmmakers present such infectious enthusiasm for, and genuine interest in, people of every stripe. Fewer still can make a successful marriage of the everyday and enigmatic. This mix of traits has resulted in a body of work that is artful yet approachable, across a wildly varied range of topics. Spookers is right up there with Florian’s best work. Who knows what he will make next, but I for one will be watching.

Spookers