My Vanua, My Practice

For artist Joana Monolagi the vanua was the classroom, and her cultural protocols and practices were her subjects. Reflecting on her practice, Joana reminds us why everything in it ties back to the vanua.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Lagi-Maama Academy and Consultancy are honoured to have been brought on by Creative New Zealand to connect with Moana Oceania cultural practitioners as part of this Pacific Arts Legacy Project. We were humbled to share time–space with Joana Monolagi at her home in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland to have a talanoa(talking critically yet harmoniously) about her creative knowledge and practice. And this is the story we were gifted, focused on two areas, ‘my vanua’ (land) and ‘my practice’.

My name is Joana Monolagi and I was born and bred in a sugar town called Ba, in Vitilevu, Fiji. I came to this country in April 1975. Got married here to Joeli Monolagi and we have four children – Seta, Philip, Joeli (Junior) and Lusia.

My Vanua

I was raised by my aunty, Siteri Marama and her husband, my uncle John Edward.

She used to say ‘from the top of the mountain to the bottom of the ocean – we are one with the vanua and if the ocean creatures or the earth were in trouble we feel it as Indigenous people because it's breathing and living – it has life’.

My aunty really taught and grounded me into who I am today. She used to tell me in detail certain things, about who I am, who we are as Fijian people, what’s expected of us as Fijian women, our role in the home, our roles in society, and for us as a clan.

My family come from a chiefly clan, and if we know ourselves (this is aunty teaching me) when we go to somebody’s house you don’t go as a chiefly family and sit in the best seats. You have to be humble and sit ‘down there’, never show yourself – the people around you should know, not for you to tell them where you should sit. I’m very grateful for her.

“From the top of the mountain to the bottom of the ocean – we are one with the vanua and if the ocean creatures or the earth were in trouble we feel it as Indigenous people because it's breathing and living – it has life.”

Not a day goes by that I don’t miss aunty, she would be here spoiling my kids rotten and teaching them the way of life. Her father died when they were very young, so she and her husband became father and mother to her younger siblings. Early in her married life my aunty discovered she could not have children, so when her siblings had their own children (my generation) they became father and mother to us also. They raised all the eldest children so she could guide them to live their lives fully as representatives of the the generations behind us.

As the matriarch in our family – nothing moved without her!

Women play a big functioning role from the beginning to the end for occasions like weddings and funerals. If somebody was getting married the family would gather to plan. Women know what to do, what’s expected of them to provide and take to the matriarch's house. They will then sort for example the masi (Fijian barkcloth) and/or mats for the couple to stand or sit on in the wedding ceremony which will then be gifted to the church from the family. Everything gets divided between the family, starting with the couple, followed by the immediate family. In funerals, women see to arrangements like what is to be taken to the church for the service and what is buried with the coffin. Men also have an important role in these occassions. It goes on from generation to generation.

My cultural institution of learning

Growing up back home we are always linked to the vanua – everything that we do as Fijians, to do with our protocols and different functions. As a young girl I would go with the matriarch of the family, whether it’s a wedding or a funeral, and help with laying the mats down. I grew up respecting our aunties, our mums, our bubu (our grandmothers) and just being obedient to what they were telling us. Bring the mat and put it over there, spread that, hang that and never saying a word back to them – like oh I’m tired – oh God forbid I say that!

You learn by being quiet, by sitting and by watching. Seeing what the mothers are doing and anything to do with ‘making’ – whether it be weaving mats or baskets, or even masi printing. I never wanted to have a go but it fascinated me. I would sit there and watch their hands working away – putting the woollen yarn on the edges of the mats and just seeing the perfect line they would make, the perfect curl, the perfect plait with the pandanus leaves. I got an invitation to have a go but I didn’t dare touch it thinking I might spoil it.

I would sit there and watch their hands working away – putting the woollen yarn on the edges of the mats and just seeing the perfect line

All these things I grew up with around me. Growing up in a small sugar town, six months of the year the mill would crush cane and six months it would stop to be overhauled, the men where I lived who were fishermen would go fishing and sell their catch to provide for their families. I would watch an uncle of mine, Billy Wise, mending his fishing line and fishing net. I was fascinated by the different knots for these different nets, watching them take shape, in a moment I would see a hole there and then it would be gone. Even watching my aunty Siteri who I lived with would go catch fish and also mend the nets when needed.

It fascinated me to watch and grow up with all these things – weaving, printing, mending and knotting. The invitation was always there to have a go at weaving or printing, but I would rather go to the plantation and dirty my hands in the soil. I would plant, I would go to the river, get freshwater mussels or go fishing.

That is until I came to Aotearoa.

‘The beginning of my making and working with masi’.

When my eldest Seta, started going to kindy, it was next door to a primary school where they held ‘drop-in’ classes for mothers whose children were at kindy. I went there really just to pass time and wait for the bell at 12pm to pick Seta up and go home. But then I started looking at what the ladies were making and thought this is silly, I'm just sitting here taking up space. I may as well go and make something. So, I joined and learnt from the ladies how to make things like photo frames and tissue box holders and using materials like lace. I continued taking these classes to kill time with the other mums until my youngest Lusia attended kindy and also continued making crafts at home.

It was during this time that Nancy Sheehan (from Fiji Social Services) called one day and asked if my children wanted to attend a school holiday programme on tapa printing and of course I said yes I’ll bring them along. A few days later I got another call from her asking if I would teach the class and I said ‘my goodness, isn’t there anyone else you know that can teach this class?’. You know, thinking in the back of my mind I know what to do but I’ve never done it back home in Fiji. So, reluctantly, I said ‘yes’, took my kids along and taught the class. It was like I always knew – it was there all along and just waiting for the opportunity to come out.

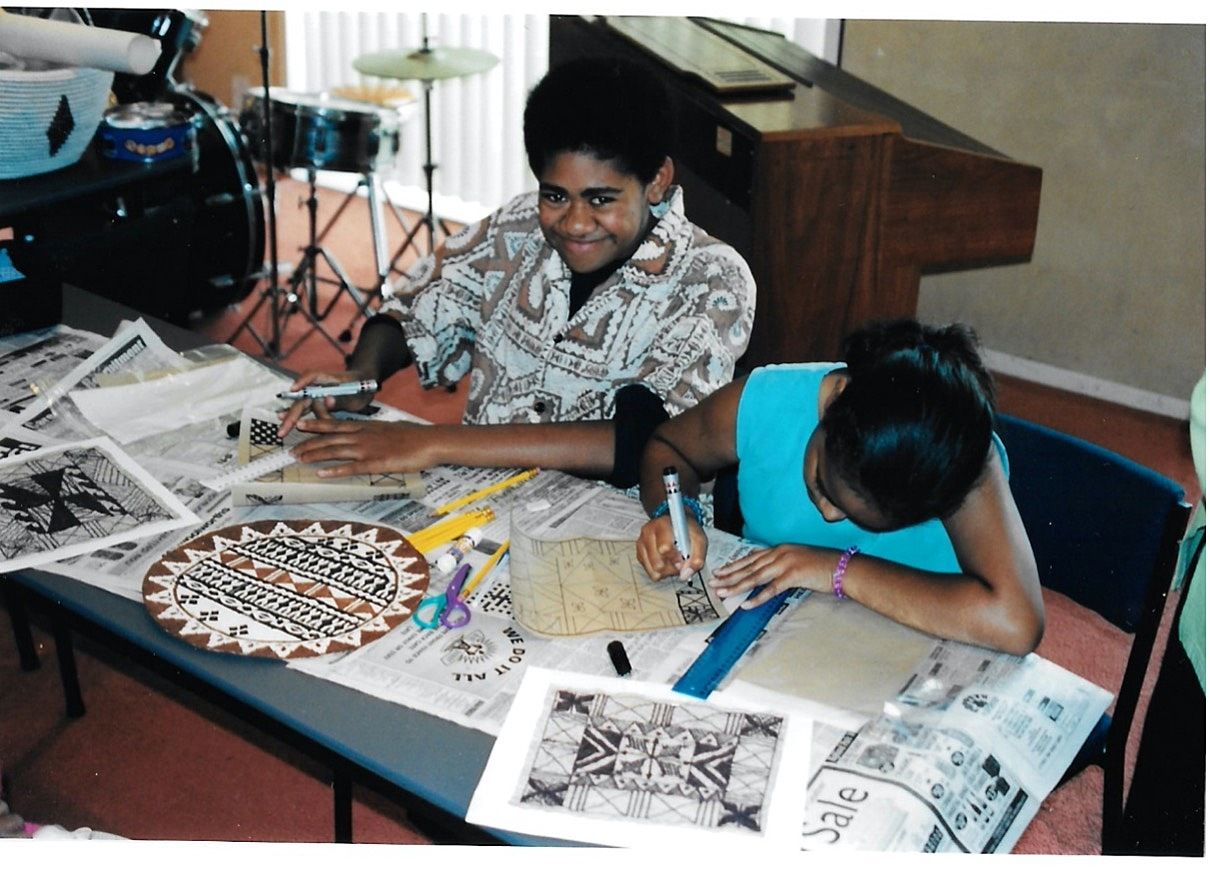

Running my first masi workshop for children as part of the Fijian Cultural Arts Programme in 2002.

L-R: My daughter Lusia Monolagi and Natanya Farrell participating in the masi workshop that I ran as part of the Fijian Cultural Arts Programme in 2002.

I still have photos of my children, they were so little but we were making things together. We made flowers, tapa printing and photo frames all using masi for that two week holiday programme. The parents also enjoyed seeing their children make Fijian inspired crafts and also wanted to have classes for themselves. In hindsight, that was the beginning of my making and working with masi. What I learnt from there gave me the opportunity to use masi but through my own lens (and the lens shaped by my upbringing back home in Fiji).

So, I’m grateful for those days I went through. It was all part of a greater master plan, and I sit around some days and I look back and say WOW – your journey, my journey – all our journeys have been pre-planned. You never know until you get there what you have been doing but for me the very thing I ran away from – I ran into.

That’s my beginnings I think.

To teach, to sustain, to nurture, we are the heart of the family, to pass on the knowledge of creativity to the next generation.

My practice: always looking back to my vanua

I’ve never had to ‘describe’ my practice because it’s something I do and who I am.

I know what is expected of me as a Fijian woman. To teach, to sustain, to nurture, we are the heart of the family, to pass on the knowledge of creativity to the next generation.

To be a maker, I look back to the vanua where everything comes from – from this sacred place. The very essence of who I am, as a Fijian woman. I look at my people and my ancestors who were so rich within their knowledge. The knowledge of vanua, the ocean, the stars and navigation, I always draw on them. The richness that they have blessed us with as Indigenous people.

Everything I do ties me back to the vanua.

The knowledge of vanua, the ocean, the stars and navigation, I always draw on them.

Running a masi workshop as part of the ‘Pacific Heritage Arts Fono’ hosted by the Pacifica Arts Centre and supported by Creative New Zealand, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, 2018. Photographer: Raymond Sagapolutele.

Masi

Working with masi and the prints that I use connects me to the vanua.

The shells tie me back to the ocean. The textile ink ties me to Aotearoa because it's what I can get here. But when I put the two of them together, one represents my practice here in Aotearoa and the other who I am as an Indigenous, iTaukei woman. The motifs I use on my masi fall into two categories; one being generic Fijian masi patterns that depict common sights such as mata ni ibe (mat weaving patterns), leaves, mountains, trees, coconuts and fans. And secondly, is when I am creating masi to tell stories of Veiqia (Fijian traditional tattooing for women), nai qia (tattooing tools) and weniqia (patterns). They are not duplicated, they are one of a kind that I am gifted with and choose to incorporate into my work.

The Veiqia Project exhibition (16-26 March 2016) curated by Tarisi Sorovi-Vunidilo and Ema Tavola, St Paul St (Gallery Three), Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Photo courtesy of artsdiary.co.nz.

My masi work Reconnecting that was exhibited as part of The Veiqia Project (16-26 March 2016) curated by Tarisi Sorovi-Vunidilo and Ema Tavola, St Paul St (Gallery Three), Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Photographer: Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai

My masi work Awakening that was exhibited at Objectspace from 1 June – 21 July 2019, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Photographer: Haru Sameshima courtesy of Objectspace.

Tanoa

There are two things that men didn’t do – veiqia and mixing the kava. Originally it was the women that mixed the kava, not the men. In making my first tanoa (yaqona bowl), I thought one way to make it was to ‘weave it’ with cane. I used to cane-weave many moons ago, so I knew I could weave it out of cane and also ‘sea grass’ rope. I added the magimagi (coconut sennit fibre) because the tanoa is special - it symbolises pregnancy. The shape of the tanoa is our womb, our tummy. The legs are ‘baby’, the more legs on the tanoa represent twins or triplets. The magimagi cord is the umbilical cord between mum and baby. The white cowrie shells tie us back to the ocean. Today you find those same white cowrie shells in the chief’s home.

The magimagi cord is the umbilical cord between mum and baby. The white cowrie shells tie us back to the ocean.

My cane tanoa as part of Rai Lesu, created with Luisa Tora for 'names held in our mouths' (8 June – 18 August 2019) curated by Ioana Gordon-Smith, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Photographer: Sam Hartnett courtesy of Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery.

Setting up the tanoa as part of Rai Lesu, created with Luisa Tora for 'names held in our mouths' (8 June – 18 August 2019) curated by Ioana Gordon-Smith, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Photographer: Seta Monolagi

Ulu Mate

When I heard the talanoa about our ulu mate (wig of human hair), I felt like I’ve always ‘known’ about it. Of course we know aye, we read it in books, we see it in the museums and then when Daren Kamali asked me to make it for his project, it didn’t surprise me that I said yes. I felt like I’ve always made it for some reason.

Going back again to when I was growing up, I went to a Catholic school. The nuns, as part of ‘Home Economics’ used to teach sewing by hand and machine, crochet and needlework. I made up all these excuses to not go when the day for ‘Home Economics’ was on. I would also get myself into trouble so I would be in detention. This meant going to clean the candle holders in church, or help the nuns arrange some flowers, and hello (laughing) today that is what I do in our church! The nuns are having the last say, especially my namesake bless her soul! Thanks to what I learnt from them, I have been able to incorporate it all into my practice now.

So when Daren asked me to make the ulu mate it just all fell into place. I drew on my childhood memories of needlework with the nuns and mending fishing nets with my uncle as I made ‘netting’ for the hair and the wig cap that I crocheted out of magimagi. All my ‘past’ experiences as a child were once again repeated as an adult with this project of making the ulu mate.

For me personally, it’s not just the making of the ulu mate, it’s the memory of it and what it holds, the richness of that era and that time. I think of why the ulu mate, why it was done, why the hair was shaved off, what does it mean? Only an Indigenous person would know – what all that means. That’s who we are as Fijians. Generations come and go, but as an Indigenous persons, we never change!

I drew on my childhood memories of needlework with the nuns and mending fishing nets with my uncle as I made ‘netting’ for the hair and the wig cap that I crocheted out of magimagi.

iTaukei school of learning

The dream is that I would LOVE a school. An Indigenous school for learning Indigenous cultural practices, and passing on knowledge to those that genuinely want to know for themselves. Somewhere to teach our young ones that have fallen through the cracks, don’t know who they are, and doing certain things in life that they shouldn’t be doing. I just want to take them under my wings and point them in the right direction of who they are!

But in sharing this talanoa with you ladies of Lagi-Maama, you have both rightly pointed out that I have been educated in an iTaukei school of learning. The vanua has been my classroom, cultural protocols and practices have been my subjects, my auntys and uncles, mothers and fathers, bubus and tais (grandfathers), and the nuns have been my professors. And that I have taken ALL that I have learnt through to my teachings today, where I am already running an iTaukei school of learning. When you put it that way, you’re right, thank you for that confirmation!

An Indigenous school for learning Indigenous cultural practices, and passing on knowledge to those that genuinely want to know for themselves.

I currently run a six-week programme teaching Fijian women the knowledge of making arts and crafts through a Fijian lens. It runs every Thursday evening at the local Panmure Community Hall and is supported by our Maungakiekie-Tāmaki Local Board. I have seven women in my group, called Na Marama ni Viti Creative Arts e Aotearoa, that include two pairs of mothers-and-daughters and I’m loving that they can see what I’m trying to explain to them. They are understanding who they are as Fijian women living in Aotearoa and it makes me very happy because they are listening. It’s something I never really had before with other past workshops I have run. One mother and daughter pair come all the way from Henderson every week and are so loyal to learning about Fijian arts and crafts. The daughter is a university student who sees these classes as a way to connect with other Fijian people.

Na Marama ni Viti Creative Arts e Aotearoa, my iTaukei school of learning, Panmure Community Hall, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Top L-R: Annah Pickering, Lisa Pickering, Xara Pickering, Mila Fong-Toy Front L-R: Israel Pickering, Twila Waqasokolala, Joana Monolagi

When I look at this little group I have, it’s not about the quantity but the quality of the work – physically, spiritually and emotionally. They do say to me all the time they enjoy coming and that they can’t wait to do the next ‘session’ – as I do them in six-week slots.

I have been very blessed to have the support of my family in all that I do.

Due to Covid-19 lockdowns last year we ran our classes online thanks to the newly gained knowledge and skills of my son Phillip who learnt filming, editing and maintaining day to day posts as the administrator of the group’s facebook page.

My daughters have also walked alongside me for nearly 25 years serving our Fijian community with our Fiji village at Pasifika Festival.

I definitely want to pass on the knowledge of what I do to my girls. At the moment, my youngest Lusia is another set of eyes. If I am doing canvas work and something doesn’t feel right, she will just come in, look and say ‘Mum you need to put this there’ and when I do it ‘aww yes it does go there – thank you’. Lusia has a good eye for the finishing look of my artwork even if she hasn't seen the beginning processes. Seta continues to do all my writing and document all the work, projects and exhibitions that I am involved with.

My daughters have also walked alongside me for nearly 25 years serving our Fijian community with our Fiji village at Pasifika Festival. And my husband Joeli Senior (now retired) keeps the fires at home burning. Also from Fiji, he complements my journey in my walk as an artist.

My family: Top L-R: Seta, Philip and Lusia Monolagi (missing Joeli Jnr) Bottom L-R: Joana and Joeli (Snr) Monolagi

When I look to the vanua, I see my aunty Siteri Marama, as the matriarch of our family. I see her teachings. I see her telling me the vanua is everything to do with who we are as Fijians – our culture, our heritage, the very essence of who we are. Our families, our languages, our dances, come from the vanua – it is a spiritual place. And as a Fijian we must know who we are in order to move forward, I keep looking back to draw on what they left us.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photograph by Raymond Sagapolutele.