Navigating the waters of Māori broadcasting

Mihingarangi Forbes on the challenges of telling and selling Māori stories

A sneak peek into Freerange Press’s forthcoming book, Don’t Dream It’s Over: Reimagining Journalism in Aotearoa New Zealand. Support the project here.

Today I am more frustrated about Māori broadcasting than ever before. Although we’ve had a few runs on the board at Māori Television and Iwi Radio, we still lead the news for all the wrong reasons in mainstream media.

Dame Tariana Turia once said that the role of Māori Television was to tell positive Māori stories. She was critical of our work at Native Affairs when we challenged the Te Kōhanga Reo Trust over expenses and governance. She believed there were plenty of Pākehā journalists producing negative stories and Māori TV shouldn’t be in that business.

The problem with Dame Tariana Turia’s statement is that the make-up of Māoridom has changed. We aren’t all the same – we are rich and poor, in positions of power, and powerless. It is the job of Māori journalists to reflect these differences, particularly if the powerful is taking advantage of the powerless. But Māori journalism’s role goes beyond holding the Māori establishment accountable – which can be challenging given the politics and power inherent in the broadcasting structures. It also involves covering a range of Māori voices and issues, and strengthening Māori content across the board.

We aren’t all the same – we are rich and poor, in positions of power, and powerless. It is the job of Māori journalists to reflect these differences, particularly if the powerful is taking advantage of the powerless.

Māori content is a catch phrase we use in broadcasting, which relates to any programme, story or article produced by Māori for Māori. These days I regard it as anything that is produced by Māori for Māori and Pākehā. Regardless, Māori content is not given the same opportunities in the mainstream media, where Pākehā stories are prioritised and a narrower view of Māori is presented.

In spite of a lack of resources, and with a broader understanding of Māoridom, we as Māori journalists are in fact the best people to investigate our own and contribute Māori content. Why would we leave that to others in mainstream media who have a proven track record of bias reporting?

In October 2007, 300 police including the special tactics unit raided the Bay of Plenty settlement of Ruatoki in a dawn operation, executed under the Summary Proceedings Act. They were looking for potential breaches of the Terrorism Suppression Act and Arms Act. Police arrested 17 people, seized 4 guns and 230 rounds of ammunition. Later the Solicitor-General declined to press charges under the Terrorism Suppression Act, pointing to inadequacies of the legislation.

Following the raids some mainstream, non-Māori media reported a one-sided and biased view of the events. The Dominion Post reported: ‘Napalm bombs, Molotov cocktails and military-style assault rifles were among an arsenal of weapons that prompted early morning police raids across the country yesterday.’ A week later Stuff reported that ‘Of the 17 people arrested, about half have links with the Māori sovereignty movement, while most of the others are self-described anarchists’.

This came as a surprise to many Māori journalists who knew and were closely related to most of those who’d been arrested. The Māori reporting on the story was quite different. Te Karere began its bulletin with ‘Fear gripped the people of Ruatoki today’. Its bulletin also covered the police press conference and comments from politicians. It presented a more balanced approach to the event.

Could the difference in reporting have to do with the reporter understanding the broader context and history of its subject? And if the mainstream media journalists had had connections into the small community, what would they have learnt from calling around and asking about the details of the raid? History and connections enable journalists to position a story within a broader context and provide several perspectives. The absence of both is apparent in the mainstream reporting on Māori issues. The 2007 raid on Tūhoe is the third raid by the Crown on the people of Tūhoe and their sovereignty. None of this was reported by mainstream media.

History and connections enable journalists to position a story within a broader context and provide several perspectives. The absence of both is apparent in the mainstream reporting on Māori issues.

The late Ranginui Walker wrote about this indifference or lack of understanding. He once said in a New Zealand Herald story about the Ruatoki raids that ‘The trouble with Pakeha is they don't have the same sense of history that Maori have. Maori have a different view of reality’. When reporter Marika Hill asked Dr Walker about the so-called terrorist training in the Urewera, he said the camps were just a show, much like when Tame Iti once fired a shotgun at the New Zealand flag.

‘What you see depicted in the media time and time again is the shooting of the flag. That's all theatre; that's all consistent with Maori culture. It looks spectacular on TV and Pakeha get intimidated by it because they don't understand it's theatre. There is no point rising up against the state, which has all the fire power,’ he said. ‘It's crazy, no one in their right minds would contemplate that.’

Dr Walker, who for many years covered significant Māori events like the Bastion Point occupation, once wrote that shows like Native Affairs were the modern day marae. He said people should stand and be blown about by the wind and shone on by the sun. Only then would we know the truth. Dr Walker was a man who sought truth. He basically did the job of the investigative journalist before Māori had any. It’s no wonder he had such influence in so many of our careers.

I was 21 when I began at Te Karere Māori News as an intern with TVNZ. I was in the last round of interns before they cancelled internships. I began with two other reporters, Moko Tini and Maihi Nikora. We all continued working in media for many years.

As a 21-year-old, my frustrations were limited to what I knew about television, which was minimal. I was frustrated when our news programme was cancelled because the tennis ran too long. I was frustrated when we couldn’t get a camera crew to cover our daily round because ONE News had commandeered them. Their news story was considered more important than mine.

That was 22 years ago, and the hopes I had of making a difference began to fade soon after I started.

Back to the future

Recently, my first boss passed away. For much of his career, Whairiri Ngata was the head of Māori and Pacific Programming at TVNZ. He had a long career prior to that as a reporter, which began at the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation where he reported in English and Māori.

In the mid-80s he came together with Derek Fox to help develop a Māori news programme for television. Mr Fox spoke at Mr Ngata’s tangi in Ruatorea and said that there had been no appetite for Māori news, but they had forged ahead regardless. In 1987 the Māori Language Act was passed in parliament, ensuring the Crown also had responsibility for preserving Te Reo. It was helpful for Derek Fox, Purewa Biddle and Whai Ngata who’d already successfully started Te Karere but, more importantly, the act helped increase Māori content across the board.

A few years later, the government reserved radio and television frequencies for Māori and in 1993, set up a funding agency, Te Māngai Pāho. By now we had more than 20 iwi radio stations broadcasting throughout the country.

1996 marked the launch of the first Māori television station, Aotearoa Television Network, and while there was a good serving of enthusiasm we were hugely underfunded and under resourced. Māori had made television before; we were great broadcasters but not many of us knew how to set up a channel.

We became the news and we all knew the angle the media would take

When one of our directors, Tukoroirangi Morgan, decided to run for parliament we – the station – became the ball in a game of politics. Tuku’s underpants became the lead story in mainstream news bulletins and papers for weeks. His only fault in that sorry saga was that he’d spent the last of his clothing allowance on expensive underwear. In came the auditors and closed the place down. We became the news and we all knew the angle the media would take. The experience was one of many (I had a serving of the same treatment recently when I ended up on the front page of the Sunday Star Times accused of taking clothes from Māori Television) that endorsed my belief that some mainstream media treat Māori issues, people and stories with an unhealthy bias.

Challenges of telling and selling Māori stories

My time at TVNZ proved to me that we were the poor cousins of the network. We battled for camera crews and editors on a daily basis, only to be handed the trainees or, to be frank, the crews no one else wanted to work with. While at TVNZ I learnt to edit my own stories because I grew tired of training the trainees. Te Karere in those days played out after Emmerdale Farm but when the tennis or the cricket ran into extended time, our show was pushed and sometimes cancelled. It was soul destroying to spend a day preparing a bulletin only to have it scrapped for a sports game. I soon realised that any attempt to protest poor decisions or facilitate change wasn’t going to happen on my watch.

When the tennis or the cricket ran into extended time, our show was pushed and sometimes cancelled

So I ended up going to mainstream, ONE News. Why not? Jodi Ihaka was there. Across at TV3, Gideon Porter was flying the flag and soon Te Rangihau Gilbert and Te Anga Nathan were appearing on mainstream news bulletins reporting stories about Māori. For all intents and purposes it appeared like we were hearing more Māori voices and issues on the 6pm news.

But the tone of the stories and the heavy-handed editing of the content soon dampened my optimism. In 2000 I remember covering Steven Wallace’s killing in Waitara. Mr Wallace was shot dead by Senior Constable Keith Abbott after a night out in New Plymouth. He was found walking down the mainstream of Waitara with a golf club and a baseball bat smashing windows. I’d made a connection with his mother, Raewyn Wallace, and remember listening to her speak about her son – the pain in her face was unforgettable. It allowed me to imagine for a moment what life in her shoes might have been like.

We didn’t report it like that. The articles and stories that ran in the days following the shooting concentrated on a Steven Wallace who was drunk or drug impaired, wielding weapons and smashing windows. Although these were all factors in the story, they didn’t answer why a man without a firearm was shot at least four times, and killed, by a man with a gun. In my opinion the media failed to challenge the police more thoroughly about why Senior Constable Keith Abbott didn’t wait for the police dog handler, use his pepper spray, shoot to wound or get his fellow constable to help him tackle Mr Wallace or use their batons.

The absence of history and connection to the community was evident in the coverage. Reporters I worked with had close relations with the police but none knew anyone in Waitara or anyone in the Wallace whanau – that part of the story was not covered. Perhaps I should have suggested stories looking at the history of police shootings in Taranaki or police shootings in general, but I didn’t. Maybe a story about the location where, 140 years earlier, the first shots of Taranaki’s bloody land wars were fired at Te Kohia Pā and how today Taranaki accounts for a third of police shootings, although it only rates tenth in population size out of sixteen regions. But this story would not have flown.

For it’s true what they say: mainstream newsrooms are top heavy with Pākehā men who have very little or no experience of things Māori. Those who’ve worked as Māori journalists – or even Pākehā journalists on the Māori round – know that when it comes to telling a good Māori news story, telling it and selling it isn’t always plain sailing.

The Pākehā norm and mainstream narratives

We can appreciate the sentiment behind Dame Tariana Turia’s statement about negative reporting of Māori issues by Pākehā because mainstream newsrooms are biased against Māori and other minorities. In research supervised by Auckland University Senior lecturer Sue Abel, her unit took a random sample of television news over 21 days and found 2 per cent of the total number of stories were Māori. Included within this were several reports on the verdict in the shooting of Whanganui’s Jhia Te Tua, the Kahui twins’ father Chris Kahui being denied bail, and a rally against child abuse.

Mainstream news producers are fascinated with stories about Māori fraudsters, Māori gangs or Māori crime. They’re not as keen on Māori success.

All these issues show Māori in a negative light compared to a sample of Māori television news, which covers a more rounded selection of Māori stories. Mainstream news producers are fascinated with stories about Māori fraudsters, Māori gangs or Māori crime. They’re not as keen on Māori success.

Many Māori are convinced mainstream news stations are racist and for good reason. Take KiwiMeter for example. TVNZ launched this survey recently – it was designed to find out what kind of Kiwi you are. One of the statements to respond to was ‘Māori should not receive any special treatment’. The answers could range from ‘strongly disagree’ through to ‘strongly agree’. Te Tai Tokerau MP Kelvin Davis called it racist and asked what the meaning of ‘special treatment’ was. He said he was left thinking ‘What’s special about having our land stolen from us, higher incarceration rates, worst health outcomes and lower educational outcomes?’ The Human Rights Commission took issue with the questionnaire, saying it demonstrated a belief bias by the authors.

Finding Māori to participate in our stories can be a chore but selling the story to the news producer is more difficult. I produced a story once on the treaty settlement funding process that was knocked back. Treaty settlements are hugely important to our country and we’re a way down the track now in settling the claims. The producer didn’t understand it, saying it was too difficult for the audience to get their heads around. The next day I wrote a story about a Māori trust that had money issues and the news boss lapped it up.

Finding Māori to participate in our stories can be a chore but selling the story to the news producer is more difficult.

This is generally what we’re up against as Māori journalists working in mainstream. I find media organisations use Pākehā New Zealand as the norm and from there anything outside is abnormal. For example, when the government reformed the Aquaculture Bill and Māori were awarded interests under what is referred to as the Sealord Deal, an article entitled ‘Maori strike gold in marine farms’ in the Independent published this: ‘This means Māori interests, allowing solely for the retrospective provisions in the legislation, will effectively be handed the equivalent sea space for 240 new marine farms - for nothing’.

Readers would have believed Māori were getting something for free.

Developing Māori content: quotas and loopholes

After the end of Aotearoa Network, Māori broadcasters had a few years up their sleeves to plan the next channel. It would have been a good time to acknowledge the lack of Māori in key industry positions and begin a training scheme, but we didn’t, and when Māori Television launched again in 2004 much of its staff were learning on the job.

Despite the lack of resources and formal training, Māori Television has been hugely successful in delivering positive Māori content. During its twelve years of developing people and building capacity, it has helped grow the industry.

Māori now have a television station and a radio network, but this doesn’t mean Māori shouldn’t be well represented in mainstream newsrooms. It’s paramount the voice of Māori is heard in mainstream. All broadcasters have an obligation to represent Māori issues under the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi.

I think this is how TVNZ gets away with employing just a couple of Māori journalists in its news or current affairs programmes, and fulfils its quota obligation

When TVNZ outsourced Marae, Waka Huia and Tagata Pasifika in 2014, many questioned its obligation to Māori as a state broadcaster. At the tangihanga of the unit’s former executive, Whai Ngata, the issue was raised a number of times on the paepae (speaker’s seat). Speakers recalled how Whai was bitterly disappointed and others called the state broadcaster ‘pokokōhua’ (an insulting swear word). Although the state broadcaster slashed these decade-long programmes, it did retain its Māori news service, Te Karere. I think this is how TVNZ gets away with employing just a couple of Māori journalists in its news or current affairs programmes, and fulfils its quota obligation. Sometimes I feel that the only reason we feature in broadcasting is as a result of our rights under the Treaty of Waitangi.

Te Karere Māori News holds up TVNZ’s Māori quota obligation and its mana too. But this programme, which is fully funded by the Māori Broadcasting Funding Agency Te Māngai Pāho to the tune of 2.2 million dollars, is positioned on a sliding schedule. On big news days they bump Scotty Morrison out of the chair for another. Twenty-two years on and ONE News is still commandeering Te Karere’s resources because it thinks it’s more important.

Who is gathering and reporting Māori stories?

ONE News, like other broadcasters, could claim it’s slim pickings when they’re recruiting Māori journalists. Perhaps it’s slim pickings because they have a certain expectation of how a television journalist should look and speak? For many years I’ve received feedback complaining about the way I sound, which is ironic given the range of accents of today’s reporters. The feedback had said I sounded too Māori, whatever that means. There certainly aren’t a lot of Māori journalists that speak the Queen’s English and the experienced ones move quickly into PR or iwi work. The combination of a good set of networks, inside knowledge of the media and being able to speak Te Reo Māori is very appealing to a raft of industries.

The feedback had said I sounded too Māori, whatever that means.

Recently E-Tangata wrote about the issue of Māori in newsrooms and claimed that one of our leading newspapers, which has been short a Māori reporter for three years now, was offering $50,000 as a salary. That’s not going to get you a flat in Papakura let alone support anyone with a family in Auckland. Many of us go further south. The office of Te Ururoa Flavell, the Minister of Māori Development, currently employs three experienced former Māori journalists. Public relations companies have sucked up a number of them too.

Experienced Māori journalists don’t last long in the media for these reasons – low salaries in comparison to PR and the woes of the knock backs in a mainly Pākehā newsroom. To succeed in a mainstream newsroom you have to want to stay but you need to be able to facilitate, build partnerships and be inclusive – even if others aren’t to you.

Recently, the Head of Te Whakaruruhau - Māori Radio Network’s Willie Jackson – attempted to lead an audit on RNZ’s Māori content. He found RNZ’s Māori content was less than 1 percent and given that Māori make up 15 per cent of the population, he said this was a bad look. His audit was average at best: he’d only used RNZ’s website for content and he’d run his audit over Christmas and New Year when the broadcaster was running different programming.

The point, however, was a good one. RNZ needed to pull its socks up and lift the Māori content, but doing that is easier said than done. In the end RNZ responded to Mr Jackson by releasing its Māori content strategy earlier than planned – there are some good initiatives that will invariably foster Māori reporters and Māori content. The growth of new reporters through the internship programme will be unique in itself. The target is young Māori – they will be trained as reporters to provide stories across the channel in a mainstream setting. The difference will be that they’ll come with Te Reo and tikanga, insight into Māori community, hapū and iwi, and a wide collection of contacts. They will make an impact on the way RNZ tells its news and also on the way it sounds.

The demands of Māori news services

Many Māori journalists would rather work in Māori news services such as Te Kāea, Te Karere and Radio Wātea because the editors there understand the position of Māori. It’s never a task to sell a worthy story.

So why not work in Māori broadcasting? Reporting inside Māori organisations reveals different obstacles. Take Māori Television for example – it’s government funded with no advertising to generate revenue so the news budgets are limited. The barriers here are resources like equipment, travel limitations and often staff.

Staff working in Māori news and current affairs aren’t afforded the same perks as in mainstream. When I started producing Te Kāea’s news bulletin, I’d be calling camera operators to come in for jobs but they weren’t answering their phones. After having a fairly frank discussion about what’s expected of them, one tells me his phone is broken and that he can’t afford to get it fixed. It beggared belief that a cameraman who is required to be on-call doesn’t have a phone provided by the company.

That changed quickly after a quick chat with Operations Manager Carol Hirschfeld; they now have phones but there’s a long way to go in order to have equality within the industry. Ngā Aho Whakaari (the Maori Screen Guild) conducted a survey last year, which was completed by 20 per cent of its membership. It found that Māori television workers were the underclass of the industry.

Ngā Aho Whakaari (the Maori Screen Guild) conducted a survey last year, which... found that Māori television workers were the underclass of the industry.

This is reflected in the government funding available. Last year the executive director of the Directors and Editors Guild of New Zealand, Tui Ruwhiu, wrote about the inequality within the industry. He pointed out that it cost $500K per broadcast hour to produce Brokenwood Mysteries, $400K per broadcast hour for Filthy Rich but at Māori Television its Head of Content Mike Rehu was asking for scripted drama series to be made at a maximum of $45K per half hour episode. Mr Ruwhiu said that was 18 percent of the per hour cost of NZ On Air funded TV drama.

Māori Television is a partnership between Māori, represented by Te Putahi Paoho (Māori Electoral College), and the Crown, represented by the State Services Minister and the Minister of Māori Development – these representatives appoint its board. The Māori stakeholders who make up Te Putahi Paoho include Kōhanga Reo Movement, Whare Wānanga, Kura Kaupapa Māori, Māori Women’s Welfare League, NZ Māori Council, Ngā Aho Whakaari, Ngā Kaiwhakapumau i te Reo, Iwi Radio Network and Te Ataarangi – a language-based organisation. This set up will shuffle and become Te Mātāwai once the Māori Language Act is passed.

The interconnectedness of the Māori establishment and the reliance on limited funding, which is attributed by that establishment, presents challenges to Māori journalism. Amongst these organisations are many individuals who hold positions of power and responsibility; the role of the investigative journalist becomes difficult if the journalist is inquiring into any of those organisations or individuals. Take, for example, our story on Te Kōhanga Reo Trust. Before we even broadcast the first story, we received an email from the chair of the Kōhanga Reo Movement, Iritana Tāwhiwhirangi, taking issue with the story, which was addressed to our board’s chair Georgina te Heuheu, which was then forwarded on to our CEO Jim Mather.

What was the intention of that letter other than to fire a warning shot at us? Thankfully our CEO Jim Mather wasn’t deterred by this kind of behaviour, but it does highlight the difficulty of remaining neutral when the organisation is set up as it is. Following on from that, Crown Minister Tariana Turia released a press statement which began with this: ‘Māori Party co-leader Tariana Turia has questioned whether Māori Television has forgotten its original purpose in the wake of its attack on Kohanga Reo.’

The statement released by Radio Wātea on her behalf went on to say: ‘This follows a Native Affairs expose, based on leaked credit card records, questioning about $10,000 in purchases made by Dame Iritana Tawhiwhirangi and her daughter in law Lynda Tawhiwhirangi, the managers of the trust’s commercial subsidiary Te Pataka Ohanga.’

Most disappointing for me was this line where she questioned whether misspending $10,000 was even worth reporting: ‘The whole way that was handled, you would have thought there was a huge amount of money that had been taken.’

Most disappointing for me was this line where she questioned whether misspending $10,000 was even worth reporting

These are the obstacles we deal with while working in a Māori framework. As a consequence of the Kōhanga Reo investigation we were blacklisted from any events run by the Māori establishment including the Kōhanga Reo’s press conference at Ngāruawāhia.

Sometimes the interweaving networks of the Māori establishment can be difficult to navigate or problematic for journalists. Willie Jackson represents various entities and has a lot of responsibility. He is chairman for the Māori Electoral College, which helps select the Māori TV board. He is the chief executive of the Urban Māori Authority, chief executive of Urban Māori Broadcasting, chairman of the Māori Radio Network, chairman of Te Pou Matakana – North Island Whanau Ora commissioning agency, political commentator for TVNZ’s Marae, broadcaster on Radio Live and chairman of a charter school board. I once asked him how many hats one could wear before being compromised. He responded that it’s different for Māori, that Māori can wear many hats.

Partnerships across forums

The connections I built at TV3 followed me to Māori Television, and while there was an existing relationship, it became even stronger. I recall one Waitangi where our relationship was probably at its strongest.

I’ve covered Waitangi for two decades and not a lot changes. The media rolls in and parks up at the lower marae called Te Tii. They stand along the fence line waiting for protesters and politicians to clash, which more than often they do. It’s no wonder those who’ve never attended Waitangi don’t ever want to because what you see on the TV news isn’t the whole story of Waitangi – the mainstream’s focus is narrow and is usually missing the celebrations, the great food, the waka displays and the carnival atmosphere that’s taking place across the bridge where most of the public spend the day. That broader context is once again missing. Instead media focuses its attention on the pōwhiri for the Crown, where in the past prime ministers have been pushed and shoved by protesters.

This Waitangi, the marae committee at Te Tii marae had decided to charge media who used the grounds and facilities. Māori TV had always provided a koha for the marae, and the charge was probably more aimed at mainstream media, which had in the past used and abused the goodwill of the marae and its facilities. One year, TV3 had decided not to set up at the marae and to concentrate on events up at the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. For that reason, TV3’s producer Keith Slater suggested that they’d just give a koha too. The marae committee wouldn’t have a bar of this suggestion so Keith, the head of news and current affairs, Te Anga Nathan and I had to hui with the committee in the tent.

It quickly became heated, with Keith Slater shaking with anger. He’d been calm and polite until a committee member began telling him a few facts about Māori, marae, koha and the treaty, to which Keith responded: ‘Look mate it’s not just your treaty, it’s ours too’. We all cracked up laughing and we followed up with a hug and a hongi. We agreed not to agree to the requirement and the next morning we went onto the marae for the media pōwhiri, where Julian Wilcox eloquently addressed the wharenui on behalf of our two networks and handed over a koha. It finished there with a harirū (handshake) and another hongi followed by a cup of tea.

It quickly became heated, with Keith Slater shaking with anger. He’d been calm and polite until a committee member began telling him a few facts about Māori, marae, koha and the treaty, to which Keith responded: ‘Look mate it’s not just your treaty, it’s ours too’

The point of this story is that if we work together with Pākehā media on a level playing field, we hear each other and together we’re able to find solutions. And Waitangi is just once a year – there are always obstacles to manoeuvre when it comes to the delivery of daily news.

The TV3-Māori Television relationship was strong for many years under the leadership of Te Anga Nathan, Julian Wilcox and Mark Jennings. Te Kāea and Native Affairs were afforded many resources at very little cost and Māori Television provided TV3 with invaluable support in their coverage. After we left Māori Television that relationship wasn’t preserved and has all but fallen away – except for a picture-sharing arrangement. The TV3 executives certainly aren’t meeting in Newmarket for sushi with Māori TV’s executives. That’s over.

The journalism minefield

Journalism, regardless of whether you’re Māori or Pākehā, is a family. When we came under fire at Māori Television from the Māori establishment it was our colleagues at other networks who covered our story. We were in a bind: we had a new CEO who didn’t like the way we reported on issues, we had a board under fire from the very people who had appointed them and Crown ministers publicly berating us.

You soon learn to navigate new terrain because as a Māori journalist nothing is a given. The government changes and the executives of Māori organisations often change with it. When you’re in between the government and boards that don’t particularly like your work, you don’t often have any other choice but to waka jump or leave.

One day I hope we have a flotilla of waka to paddle and that the captains of those waka learn to share the navigating with the helmsmen and the paddlers. As a Māori journalist nothing is ever a sure thing. The Māori media industry is often like a minefield and that leaves you two choices: be patient and wait to be blown up or run quickly through the field, sidestepping as you go.

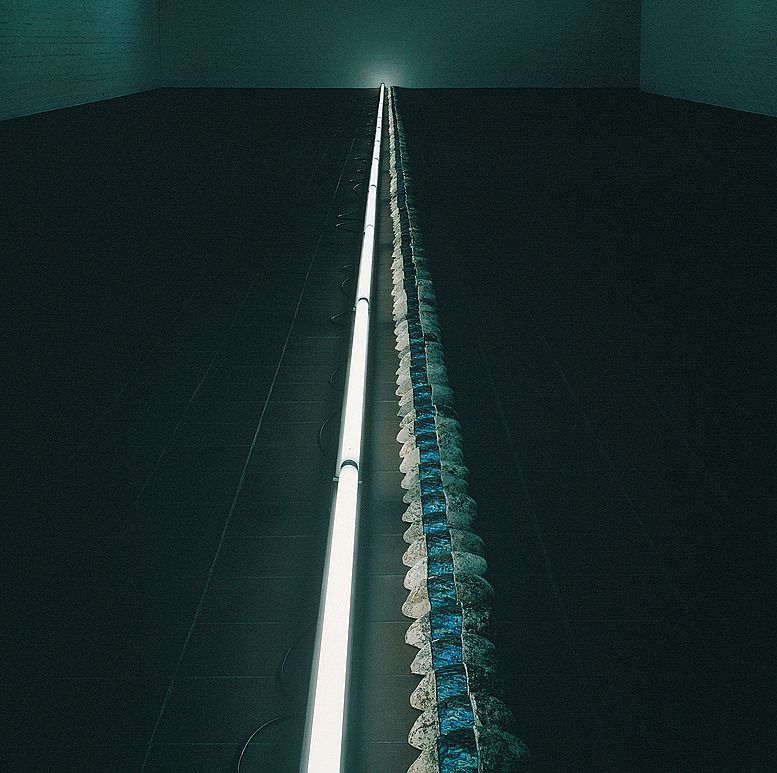

Main image: Ralph Hotere and Bill Culbert, Pathway to the Sea – Aramoana (1991). Paua shells, rocks, fluorescent tubes. Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, purchased 1993. Photograph by John McIvor, courtesy of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

This essay will appear in Don’t Dream It’s Over: Reimagining Journalism in Aotearoa.