Old Asian, New Asian

Labour's recent use of leaked real estate statistics have brought to the forefront a long history of anti-Asian sentiment, and it's something we should discuss, writes K. Emma Ng.

Labour's recent use of leaked real estate statistics have brought to the forefront a long history of anti-Asian sentiment, and it's something we should discuss.

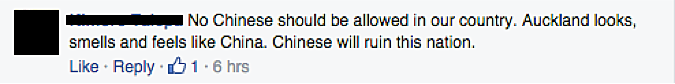

It’s hard not to read the comments. Over the past few weeks I haven’t been able to help it, losing myself in the folds of the chain of reply. The (particularly active) New Zealand Herald Facebook page has been my forum of choice, and while there are some people discussing Auckland house prices, it's the ones who feel they now have license to espouse some plain old anti-Chinese sentiment that keep me coming back.

The most hurtful are those expressing frustration with the number of Asian people they see around them (I’m using ‘Asian’ and ‘Chinese’ interchangeably because that’s how it’s so often (inaccurately) used, even though that’s like using ‘Brazilian’ and ‘South American’ interchangeably). It makes me feel like my presence in the place I call home has been merely tolerated – until now. There’s no sense in reading the comments, and there’s no sense in reading vitriolic hate speech about Chinese people – regardless or not of whether it’s about me. I know that. I really do. It would be easy to attribute these comments to people too distant to impact my life directly, writing them off as not worth engaging with. But it’s as though a plaster has been ripped off, and while at first it stung in the open air, all I want to do now is examine and pick at the scab.

Whatever the intentions of the Labour Party, and whatever the outcome of the stats vs. stats fight-to-the-death that has been initiated, it feels as though a lid has been lifted on New Zealand’s lingering sinophobia. Comments of the ‘we’ve all been thinking it’ variety cut to the heart of it from one angle, while the reactions of Chinese New Zealand bloggers (laying out their own experiences of racism in New Zealand) come at it from another.

Public reaction has followed a familiar parabola: outrage, backlash, backlash-to-the-backlash, and a call to return to ‘the discussion that matters’. Unfortunately, whether or not the targeting of the Chinese was largely pile-on racism, abandoning this discussion in favour of focusing solely on that of offshore investment would shut down this opportunity to talk openly about the place of Asian people in New Zealand, once again leaving these issues simmering and suppressed.

Debate has diverged into two conversations worth pursuing. Pushed along by political agendas, Auckland’s housing market will continue to be discussed publicly, but there is less motivation for sustaining a collective conversation about the continued vulnerability of Chinese people in this country.

Labour's use of the leaked real estate statistics flamed easily because they blundered into a fragile context already conditioned by tides of anti-Asian history

Labour's use of the leaked real estate statistics flamed easily because they blundered into a fragile context already conditioned by tides of anti-Asian history. Sinophobia in New Zealand is not new, and neither is it benignly located in the past. Let’s talk about non-residents buying land in New Zealand. Let’s not present ethnicity statistics in the context of a debate about residency and allow the two to become conflated.

A 2010 Human Rights Commission Report found that Asian people reported higher levels of discrimination than any other minority in New Zealand. However, such instances of discrimination are often discussed as unfortunate anecdotes, perpetrated by a small number of people that hoard strong xenophobic attitudes.

Today, much of New Zealand’s racism is fairly insidious, underscored by a misguided belief that Kiwi and Chinese identities are mutually exclusive. Each time a stranger greets me with ‘konichiwa’/‘nihao’ or asks me where I’m from, I know they’re seeing me as Asian first – my New Zealand-ness doesn’t enter the equation until I refute their reading. Australian Olympian, Dawn Fraser, recently criticised the behaviour of tennis players Nick Kyrigos and Bernard Tomic, suggesting ‘If they don’t want to be Australians then maybe they should go back to the country where their parents come from’. Morgan Godfrey, writing about Fraser’s comments, suggested that, ‘this is the reality of modern racism: shaped by history, carried out by otherwise well-meaning people and almost impossible to name.’

It strikes me that Antipodean sinophobia is probably driven by how vast the differences between China and New Zealand are perceived to be. The term sinophobia therefore seems particularly appropriate, with –phobia indicating attitudes driven by a fear of difference and the relative unknown.

To many New Zealanders, an understanding of contemporary China seems well out of reach, and is framed in the vaguest and most polar of terms: China is enormous where New Zealand is small; it has a poor human rights record while ours is a source of relative national pride; and it is ancient when we are young. Real and perceived differences in everyday life and values also have an impact, whether it be a greater predilection for buying real estate or removing shoes at the front door. This cultural gulf, paired with a lack of concrete understanding, makes it hard to relate. It makes empathy hard, and ultimately it serves to deepen insecurities about the potential influence of China (on New Zealand) as its economic power continues to grow.

As journalist Keith Ng has noted, even if it’s overseas Chinese buyers who are perceived to be a threat, it’s local Chinese who often become the target of reactions to this threat. My own recent experiences range from a couple yelling ‘Go back to China!’ and ‘Why are you even in New Zealand?’ at me down Courtenay Place until I was out of sight, to being the recipient of more well-intentioned assumption and prejudice. Early last year I was interviewed for The Dominion Post, and as we sat down to coffee my interviewer said, ‘You speak English very well!’, before trying to claim she meant it in comparison to ‘our hick’ (inference: white New Zealand) pronunciation (she spoke fine, and I have a New Zealand accent). She ended the interview with, ‘But you’re quite Westernised aren’t you’ – less a question, more a statement.

As a second-generation Chinese New Zealander, this was an insulting and alienating experience, yet as is often the way, I did not call her out. Godfrey’s characterisation of modern racism springs to mind again here – ‘well-meaning people and almost impossible to name.’ Couched as a compliment, this well-intentioned discrimination both caught me off guard and made me feel it would be unreasonable to verbalise my feelings with her.

This journalist had no trouble automatically assuming the position of arbiter, with the power to pass judgement on my identity in relation to the whole (and based largely on my appearance), driving a wedge between the ‘Chinese’ and ‘New Zealand’ parts of my identity. This was a woman conducting an interview in a professional situation, and for every one of these sentiments that makes its way into an actual interaction with a person of Asian ethnicity, it’s deeply uncomfortable to think about how much xenophobia is being expressed within families or between friends, being reinforced and affirmed (and hopefully, sometimes challenged) by others behind closed doors.

The Human Rights Commission report hints that this might be the case, with ‘one in two New Zealanders [who] feel the recent arrival of Asian migrants is changing the country in undesirable ways‘.

One in two.

This suggests it’s time to stop characterising experiences like mine as outlier occurrences that have little real impact on the people who experience them. As it stands, while these events might be shared among friends, they are rarely discussed as part of larger patterns of racial discrimination in New Zealand.

One in two New Zealanders feel the recent arrival of Asian migrants is changing the country in undesirable ways

The difficulties of shining a light on modern racism aren’t helped by the relative invisibility of New Zealand’s anti-Asian history. Even the Chinese Immigrants Act, passed in 1881, is a little known part of New Zealand’s narratives, despite Helen Clark formally apologising to the Chinese community on behalf of the Government in 2002.

Before the Chinese Immigrants Act, Chinese were invited to New Zealand when their labour was needed on the goldfields but anti-Chinese movements quickly gained momentum as this work dried up. The late 1800s saw the emergence of organisations such as the Anti-Chinese League, the Anti-Asiatic League, the Anti-Chinese Association, and the White New Zealand League.

The Chinese Immigrants Act enforced a Poll Tax that required every Chinese person entering New Zealand to pay £10. In 1896 this was raised to £100 – equivalent to $18,500 in 2015. The Act also imposed a severe quota on the number of Chinese immigrants that could enter the country; by 1896 ships landing in New Zealand could only bring one passenger per 200 tons of cargo – a steep increase from the ratio of one passenger per 10 tons in 1881. The tax was waived in 1934, but wasn’t repealed for another decade.

It was almost impossible for women to migrate during this time in order to discourage Chinese families from settling here in New Zealand. With their families unable to join them, it was hoped that most of the Chinese men who did come to New Zealand would eventually return to China rather than live out their lives in this country. Those who did manage to immigrate faced further discrimination once here. Chinese in New Zealand were not eligible for the pension, were refused permanent residency, and were treated as second-class citizens. Much of this discrimination barely enters our collective understanding of this country’s history.

In Auckland and Wellington for example, the ‘Chinatowns’ of Greys Avenue and Haining Street have long since faded. The flow-on effect is an erasure of the visibility of the Chinese in these cities’ histories, and a forgetting of racially-motivated violence such as the murder of Joe Kum Yung in Haining Street in 1905. Lionel Terry, who murdered Joe Kum Yung, did so to draw attention to the anti-Chinese cause, which sought to rid New Zealand of Chinese people. Following his arrest Terry drew a large amount of public sympathy in a particularly nasty kind of ‘we’ve all been thinking it’.

For Asian residents who have been calling New Zealand home for a long time, it’s particularly stinging to feel unwelcome once again. Following the discrimination experienced by the Chinese in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many worked hard to be perceived as quiet and conscientious. As in the United States and Australia, many of New Zealand’s early Chinese migrants set up small businesses, so as not to be seen to be competing for the same work as white New Zealanders, and preferred self-employment to the difficulties of finding jobs with white employers.

Beven Yee, a Chinese New Zealander and social scientist, explores the ways in which Chinese New Zealanders have negotiated their place in New Zealand society in a chapter of Unfolding History, Evolving Identity: The Chinese in New Zealand:

'Given both the constraints of the unspoken contract and the obvious physical distinctiveness of Chinese in public settings, it should come as no surprise that Chinese are deeply concerned about their public image.

Minnie: [My parents were very] conscious of the fact that they were Chinese and had to present a better front. [And] we all had to put on our best behaviour. Chinese never got into trouble, Chinese never did this, Chinese never did that, [Chinese were] more law-abiding.

Derek: [There was] pressure on [us not to] get into trouble… we might get sent out of New Zealand…

Minnie: Or discriminated against.'

Taking on the mantle of a ‘model minority’, Chinese immigrants were largely able to avoid negative attention, and anti-Chinese prejudice subsided around the 1950s and 60s. At this time assimilation was actively encouraged by the government, who denied entry to Chinese language teachers in 1949, and between 1951 and the 1970s allowed the entry of Chinese migrants only if they already had family in New Zealand.

In keeping their heads down and ‘playing by the rules’, the Chinese developed a certain pride around cultivating this image of a valuable model minority – with perceptions of intelligence, financial success and business savvy tied up in this. Jumping ahead to today, the model minority stereotype is widely seen to be a harmful one, both to Asians and the minorities typically excluded from the stereotype. Buying into the model minority paradigm denies true diversity and encourages ‘good minority’/’bad minority’ categorisations that pit different ethnic groups against one another, feeding the sense that they are in competition for a secure place within the dominant hegemony.

Interesting questions arise around prejudice as a kind of system justification: when a minority is perceived to possess positive traits such as wealth, intelligence, or privilege, they become easy targets for public denigration because it’s psychologically palliative to do so. In this case, it’s the particular intersection of apparent economic power with racial difference that make ‘The Chinese buying houses in New Zealand’ unacceptable. This is evident in the sense of entitlement to land that has sparked these debates (characterised by comments of the 'Asian buyers pushing houses out of reach from my hard working Kiwi son/daughter’ type) that implicitly values the ‘hard work’ of white workers over that of others.

Minorities in New Zealand are stuck in a cycle of lose-lose discrimination that sees them treated with resentment when they’re perceived as socio-economically valuable and with disparagement when they aren’t.

Minorities in New Zealand are stuck in a cycle of lose-lose discrimination that sees them treated with resentment when they’re perceived as socio-economically valuable and with disparagement when they aren’t. Just as Chinese migrants were initially invited to New Zealand for their labour, a manufacturing boom in the late 1950s saw Pacific Island migrants welcomed to New Zealand to take up these unskilled and semi-skilled jobs. Writing for Te Ara, Paul Spoonley describes how when economic conditions became difficult in the 1970s, ‘Populist opinion regarded them as taking the jobs of New Zealanders. Pacific Islanders were blamed for the deterioration of inner-city suburbs, and for law and order problems.’ Having come to be seen as a drain on New Zealand society, Pacific migrants were widely considered unwelcome, culminating in the ‘Dawn Raids’ of the mid 1970s.

Flooding the Chinese with negative attention has also brought to the surface the complexities of the internalised racism within New Zealand’s Asian community – perfectly encapsulated in a Facebook group I came across called ‘NZ Property – Residents ONLY!’. Started and administrated by someone who self-identifies as Asian, they have rushed to protect their own self-interests and ‘defend’ New Zealand against overseas Asian investment, at the expense of others who belong to the same minority.

New waves of immigration over the last twenty years have rapidly grown this country’s Asian population. In the most recent census, those identifying as Asian made up 11.8% of New Zealand’s population (74% identified as European, 14.9% identified as Māori, and 7.4% identified as ‘Pacific peoples’). No longer a small (seemingly unthreatening) minority, New Zealand’s well-established Chinese families often find it hard to relate to new migrants who come here under very different circumstances, from different parts of China and Asia, and who don’t face the same pressures to assimilate now that New Zealand’s Asian population is larger.

I’m not interested in drawing distinctions between these two groups. The ‘my family has been here longer than yours' argument is a dangerous one that reinforces the notion that Chinese in New Zealand are recipients of a benevolent tolerance predicated on their ability to play the assimilation game and pass as ‘more Kiwi’/‘less Asian'.

To be accepted in New Zealand, Asian minorities are made to work for their citizenship twice over: having been granted approval from the state, we must then diffuse our racial and cultural difference to seek approval from its dominant subjects. This is the part of me who got embarrassed when my parents spoke the odd bit of Cantonese in public, or proud when school friends told me I was different from other Asians. Internalised racism is a pretty horrifying thing to grapple with when you become aware of it.

Asian minorities are made to work for their citizenship twice over: having been granted approval from the state, we must then diffuse our racial and cultural difference to seek approval from its dominant subjects

In recent years it’s been encouraging to follow the success of Lydia Ko, a Korean-born, New Zealand sports woman. As well as raising the visibility of Asian New Zealanders (particularly newer migrants), Ko has helped to break down some of the perceptions that Asian people cannot excel in activities such as sport, which are so strongly tethered to a performance of national identity here. However, the sport of golf also comes with connotations of privilege, and with her down-to-earth, hardworking image, Ko probably reinforces certain ‘model minority’ stereotypes. Whether or not this is true, it is still significant that she has earned the respect of the world’s golf audience, which is typically older, whiter, and male.

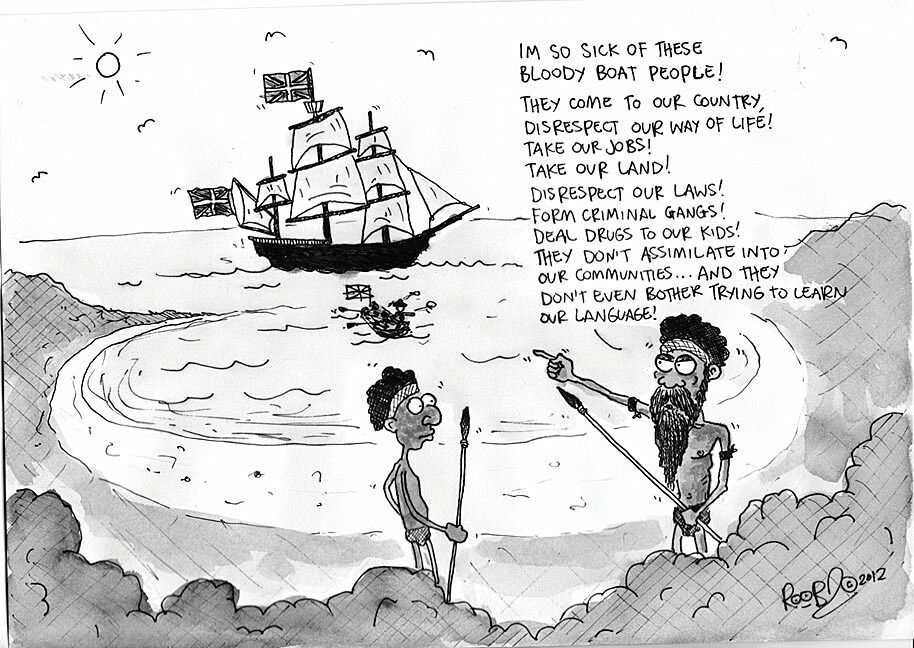

In a country where many of us are tangata tiriti, drawing distinctions between new and old migrants (and by extension between migrant groups based on ethnicity) is a morally untenable position. Doing so requires us to forget that at the point of immigration we are all new immigrants, and to deny others the opportunities we have been afforded is essentially pulling the ladder up behind us.

If we find it difficult to empathise with the motivations for moving to New Zealand, we have forgotten that we are all privileged to be here. A New Zealand that perpetrates racial discrimination in any form is built on a misunderstanding of our nation’s biculturalism as a relationship between Maori and a white settler society, rather than between tangata whenua and all tauiwi.

Let’s be clear. I do not want to be told that the topic of people with Asian surnames is closed for discussion by those who initiate and perpetrate conversations on this basis, whether intentionally or not. Reframing a discussion of Asian house buyers in more politically correct terms denies us the opportunity to turn this dialogue into something constructive.

I do not want to be told that the topic of people with Asian surnames is closed for discussion by those who initiate and perpetrate conversations on this basis

As the ethnic makeup of New Zealand continues to change, the nature of our race relations will continue to impact the very real everyday experiences of those who live here. We are in a position to build on the rich exchanges that have already taken place, but we need to keep talking. It’s time to ask ourselves some difficult questions about exactly what it is we fear, and be prepared to hear some difficult answers.