Orange Isn’t the New Black: Why we restrict prisoner voting rights

Anna Whyte looks into why in New Zealand, unlike many developed nations, prisoners aren't entitled to vote in national elections.

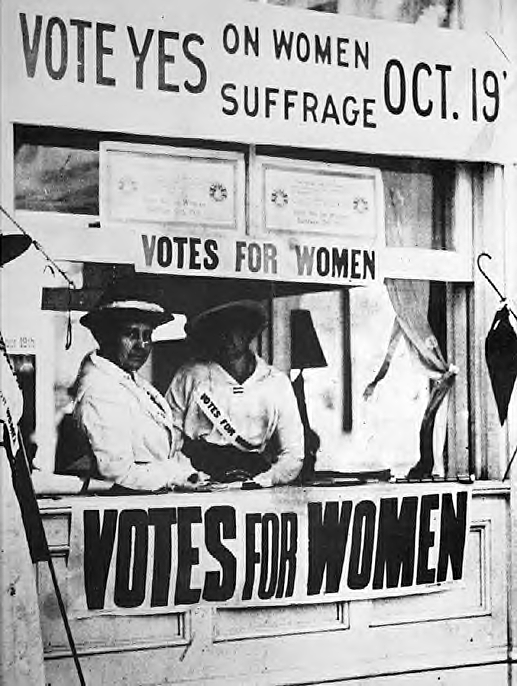

My great-grandmother was born into a world where women weren’t considered human enough to vote. She was destined to a life largely deprived of what’s now considered the democratic right of nearly all New Zealanders. We see the citizens of broken nations lining streets amid death threats just to write their opinion on a bit of paper, or we hear how they’ve lost their lives in the fight for their say. It feels wrong that a person could confiscate something as precious as a vote, which impacts how you want your taxes used, the direction you feel the country should go in, and even the kind of place you want to leave to your children.

The 2011 election marked a return of the blanket ban on a prisoner’s right to vote. One-term National list MP Paul Quinn successfully sponsored a private members bill in 2010 to completely extinguish the voting rights of prisoners. The Amendment Act passed by a mere five votes, reinstating a ban on hold since the 1993 Electoral Act allowed those with 3 years left on their sentence able to exercise their voting right. In Quinn’s opening address on the Electoral Amendment Act, he said “I think it is important to pause for a moment and reflect on the concept of imprisonment and what it’s about. Imprisonment was looked on as a temporary exclusion of a person from the community and from the rights associated with membership within that community.”

In the months leading up to elections we’re inundated with the message that voting’s important, yet a bill with the slimmest majority revoked the rights of a group who were thought not be deserving of something considered a fundamental human right. Meanwhile, should the political left win the next election, an equivalently tiny majority will restore prisoner voting rights.

When considering whether it’s a breach of prisoners’ human rights for the right vote to be removed, it’s important to note that in many ways it's a moot point. Prisoners have had their Right of Movement, their Freedom of Association, and parts of the Right to Peaceful Assembly removed already.

In addition to these rights and fundamental freedoms, the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 states in section 12 that every New Zealand citizen who is of or over the age of 18 years —

a. has the right to vote in genuine periodic elections of members of the House of Representatives, which elections shall be by equal suffrage and by secret ballot;

The Attorney-General Chris Finlayson produced a report deeming the blanket disenfranchisement of prisoners inconsistent with New Zealand’s Bill of Rights. This view coincided with that of the Human Rights Commission and the New Zealand Law Society. Under section 4 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, the rights contained within the Act should be subject only to “reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” It’s far from clear that limiting prisoners’ voting rights is demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

Current Minister for Corrections Peseta Sam Lotu-Iiga told me his party’s philosophy on rescinding prisoner voting rights was based in part on historical precedent: “For most of the last century, sentenced prisoners did not have the right to vote… The rights of law-abiding citizens should come before the rights of criminals. This law makes it clear that our democratic rights as citizens include obligations to obey the law. When people break the law and are sentenced to prison, they have not met these obligations, and they lose the right to vote while they are prisons," he told me.

This raises the question of whether punishment or rehabilitation is the main focus of custodial sentences, and what implications this has for prisoner voting eligibility. The removal of rights to punish prisoners is what some groups say is essential to protect society and give victims justice.

The Sensible Sentencing Trust (SST), according to their website, “unashamedly exists to advocate on behalf of the victims of serious violent and/or sexual crime and homicide in New Zealand.” The SST lobbies for harsher sentencing, which they believe will reduce re-offending. Jayne Walker, SST Coordinator and Victim Advisory Leader, and Leigh Woodman, National Victims Portfolio Manager, emailed me with their views about why their organisation believes prisoners shouldn’t vote.

The offender had a choice whether or not to commit those crimes, unlike their victims. The SST believe you forfeit certain rights when you commit a crime and as a consequence are imprisoned, so the SST agree with prisoners not being allowed to vote.

Perhaps unexpectedly, this is a view sometimes shared by former inmates.

Colin Greenwood, a former inmate at Christchurch men's youth prison, told me he didn’t think prisoners should be allowed to vote. “They have had their freedom taken from them for many different reasons, however I feel the underlying cause in most cases is stupidity… It would be a waste of time and resources for the Department of Corrections.”

Greenwood's first-hand experience of life in prison has informed his view that the lack of voting rights wouldn’t affect those in prison. “I don’t think it’s detrimental for the prisoners at all. In fact a majority of them may not even be aware it’s an election year. Most are the type of people who wouldn’t make the effort to vote under normal circumstances. Same goes for the public, I'm sure most are unaware of prisoners voting rights and couldn’t care less about the rights of people deemed unfit for society.”

However, the numbers don’t back Greenwood up. Figures released from the last election (and presently the last election in which could prisoners had the franchise) show that 628 of the 856 prisoners on remand from Serco prison in Mt Eden voted. That’s around 73%, a mere 4.9% lower than the national average of 77.9%. This debunks the theory that people who’ve been in prison aren’t interested in voting. Regardless, when considering whether a group or section of society should have the right to vote, the degree of interest that this group supposedly has in voting is an irrelevant consideration, and one that would’ve been familiar to my great-grandmother: it was used most prominently in the face of suffragettes to argue against the right of women to vote.

Despite the view from many in society that prisoners shouldn’t vote, Arthur Taylor — an activist for prisoner rights and current inmate of Auckland’s Paremoremo Prison — wrote to me to discuss the imperative need for prisoners to retain their voting rights.

Prisoners pay exactly the same taxes as anyone else... so should have a say on how their taxes are spent. The American Revolution stated ‘no taxation without representation’. Countries that New Zealand likes to compare itself with – Australia, European Union countries, Canada, all have voting for prisoners (Germany encourages prisoner voting to promote civic responsibility). In most places… when there has been a prisoner voting ban, their Supreme Courts have struck them down as unconstitutional.

Taylor says the removal of rights and continual punishment could be detrimental to a prisoner’s rehabilitation. “Society can legitimately impose punishments for wrong doing. But… it is wrong to take away voting for non-punishment reasons. That’s what you’re doing if prisoners who have completed the punishment part of their sentence are banned from voting,” says Taylor. “It seriously undermines prisoner rehabiliation, and once you start taking basic human rights away then you undermine everyone’s human rights… We are human beings. As said in court, if you take a group in society’s voting rights away (in this case prisoners), that creates a dangerous precedent.”

Whether prisoners deserve additional punishment to the extent of the removal of a condition in the Bill of Rights is highly debatable. Arguments for their vote removal include the fact that prisoners would have a say on who creates and amends the laws that they’ve broken, but the likelihood of a party voted in by prisoners based purely around prisoner rights or releasing dangerous criminals into society is about as realistic as New Zealand deciding to change its national sport from rugby to croquet. If the arguments for removing their voting rights don’t add up, then what effect does the removal have on prisoners?

Anna Goble is a volunteer for Law-for-Change, an organisation of young lawyers and law students who donate their time to helping with rehabilitation of inmates. Goble meets with prisoners regularly to teach music and to interact with those behind bars.

Many of the prisoners I dealt with are people who have had hardships in their lives or have lacked the capacity or support to go in the direction they wanted with their lives. Never in my encounters did a prisoner blame the Government or complain about the system… They talk about what they intend to do when they get out, they have hope, and they are looking to a future.

Anna believes the rehabilitaion prospects of allowing prisoners to vote outweighs using its removal a punishment tool.

So why doesn’t the Government give them the right to vote? The one tick they can exercise once every three years to aid and contribute to both their positive future after successful rehabilitation and to contribute to the society they want to be a part of after their sentence is up.

Kelvin Davis, MP for Te Tai Tokerau and Labour Spokesperson for Corrections, outlined Labour’s plans to restore prisoner voting rights. “We would restore the right for prisoners with sentences of less than three years to vote in central and local elections… We should encourage them to engage with society in preparation for their release.”

This view is shared by the Green Party, with MP David Clendon suggesting that very few inmates “will not at some time return to society, and so it is to no-one’s advantage to further alienate them from society in the way that removing voting rights must do. We should on the contrary be striving to keep people socially (and indeed politically) engaged, to facilitate their eventual social reintegration.”

So what does excluding prisoners from voting actually achieve? Does it punish those who inflicted crimes upon innocent citizens, or is it extra punishment for those who are already being punished? Does it mean society should cut down on other provisions that prisoners currently have a right to, like food, heating and education? New Zealand has the seventh highest imprisonment rate of the OECD, just behind Mexico. It costs about $90,000 to keep a person in prison for a year, making our high incarceration rate a heavy burden on the taxpayer. Is removing a right that can help facilitate even the smallest contribution to rehabilitation (and one that has no direct negative implication for victims or society) completely counterproductive? Or is it just another way to keep prisoners on the lowest rung of the hierarchal ladder?

The extraordinarily high incarceration rate of Māori also presents voting ban issues. Over half of those in prison are Māori, even though their general New Zealand population sits at approximately 15%. This skewed rate has been criticised by a United Nations delegation who visited last year. According to the delegation, it’s illegal by international law for any bias that exists which has led to these rates. Then there’s the potential breach of Treaty of Waitangi rights involved in disproportionately disenfranchising the Māori vote. Arthur Taylor is currently awaiting a priority hearing by the Waitangi Tribunal ‘on the issue of Māori prisoners being deprived of a Taonga’ — in this case, the vote.

The high number of those living in prison coming from a lower socioeconomic background in New Zealand society raises another implication for prisoner voting. There’s an enduring correlation between low socioeconomic status and an increased likelihood of voting Labour. Although the number of prisoners not eligible to vote in the last election wouldn’t have been large enough to make a difference to the outcome, that doesn’t exclude the possibility of it making a difference in future elections, and leads to the tricky conclusion that a minority group should not have their voting rights in the hands of those on the receiving ends of votes (MPs in parliament).

Dr Paerau Warbrick is a lecturer at Otago University, and a barrister with a history background. He spoke of prisoner voting rights as a matter that could potentially go beyond the rule of parliamentary supremacy.

This issue of voting rights of people in prison is probably going to be an issue for the Supreme Court. The question for the judges is how far Parliament can legislate on who is eligible to vote and who isn’t. The courts always left open a possibility that they may not enforce a rule of Parliament if it goes against fundamental legal rights… So, in legal theory there is a mere possibility of the courts invalidating an Act of Parliament… Now, the question is whether the disqualification of prisoner voting rights is such a fundamental right in the 2010s.

Despite the low likelihood of the Supreme Court acting upon this, this does open up other measures that can influence whether or not prisoners should be allowed to vote. The possibility of Labour and the Greens instating, and then National and their parliamentary allies retracting a minority group’s voting rights every ten or so years isn’t just a case of going around in circles, it’s a dangerous precedent. Given the undesirability of this issue being in a state of perpetual flux, it may be timely to consider whether it’s appropriate to entrench the provisions of the Electoral Act with a super majority (requiring a 75% majority in Parliament to effect a change).

There are still places in the world where women and those in the queer community have no say in who runs their own country. In New Zealand, half of the population were denied their voting rights based purely on their gender, while another large percentage could have been incarcerated for up to seven years based on their sexual preference. Both of these groups fell into in the same position as contemporary New Zealand prisoners – but we’ve since come to our senses. In the six years prior to New Zealand’s 1986 Homosexual Law Reform Act, 879 people were convicted by what is now seen as an archaic — and to many, incredibly insulting — law. It shows that the law is ever changing. New policies are brought in, amended, and overturned. Perhaps a small number of those behind bars right now won’t be considered criminals in a decade. With that in mind, is it appropriate to let parliament decide who ultimately has the right to vote them in or out?

When I began writing about this topic, it was purely on the basis of gathering enough information to make an informed decision myself. I’ve certainly developed opinions and views, but it shouldn’t be up to me to decide. Yet I have the privilege of voting for a party that may or may not give a group of people — a group who have no say in it themselves — the right to vote. The right of any group to vote shouldn’t be tossed around between political parties like a social tennis game.

Voting’s a right that determines the character of the country we live in, and for prisoners it’s a right that’s been removed despite no proof of detrimental effects on society, and by only a bare majority of votes. If prisoners do indeed deserve to lose their rights, it needs to be shown just how it benefits society to have a section of New Zealand without a say in our elected government. To some people, voting is just another day with just another name running our country. But to others, like my great grandmother and many of those without voting rights, the right to vote deserves more respect than a society that doesn’t care — or to know that with every election comes just another debate on whether they are human enough to vote.