A Period of Absent-Mindedness

Harrison Christian on a Northland summer

As the Aotearoa New Zealand summer starts to fade into the haze, Harrison Christian writes on family, the elements, and the way time stops in the Far North. Illustrations by Lennie Galloway.

We are screaming, spitting, pissing and blowing out snot as we paddle through each cold assault of whitewater. I have read that cold water immersion releases a cocktail of endorphins in the brain, and I believe this to be true. Before we go into the sea we're hot and red-eyed and slightly nauseous from being woken up by the heat. But as soon as we submerge our heads (after allowing the water to creep agonisingly to our genitals), we emerge baptised and reborn. We sit up on our boards in the gentle rolling swell past the breakers; catching our breath, wiping sunblock from our eyes, and spitting and pissing and blowing out snot.

The whole commercial culture surrounding surfing - and even and especially the itchy exercise of watching surf videos - is infinitely remote from the actual psychic experience of riding a wave. This might sound like sentimental beach mysticism, but the giddy presence of being on a clean-peeling face is totally esoteric and basically incommunicable. It is so brief and mysterious that it never quite loses its newness, and feels as though it's being re-discovered each time it occurs. So we force ourselves to re-discover it each day. We rub block into our faces, and pull on damp rashies, and carry our boards in unhurried procession down to the beach.

It is January. Our days are filled with a series of rituals, and governed by the rhythm of the tides. Surfing, pétanque and tuatua harvesting are verbally scheduled - it seems somehow vital to the harmony of The Camp to always be about to do something - and then carried out with a sense of monastic duty. All the hostility and tenderness bound up in old friendships plays out in sparse logistical conversations. Board games take on a special ceremonial significance. I have spent a handful of hours earnestly looking forward to a game of Scrabble against my mother.

Our bodies are brown and saline. Our hair is thick and coarse; the soles of our feet have turned the colour of tar seal. Our moustaches are curling into our mouths. And our minds are incredibly slow. The long hot days have brought on a kind of stripped-down mental functioning, where time-concepts like dates and days of the week become as distant and pointless as the memory of yesterday's breakfast. Jandals and half-drunk beers vanish and re-appear in odd places. Napping is easy and almost necessary. Central to this experience is a feeling of ever-increasing, distinctly physical bliss - like a perpetual yawn, or being stuck in the moments before sleep.

We pull handfuls of tuatuas out of the knee-deep tide. It's a bumper season. Every toe-twist finds seemingly endless clusters of the shellfish in their beds of soft sand, and they come out spitting water and pulling in their tongues, and after debating whether we have too many or too few, we take them clacking up the beach in a netted sack. At The Camp we lump them into a frying pan, splash them with white wine and steam them open; exposing their small orange bodies, which taste sweet and fill the kitchen with a gamey ocean smell.

The Bay - a tiny settlement without so much as a dairy for most of the year - is full of families and New Year's Eve revellers and day-trippers and travellers, who all converge on the grass to witness The Tractor Spectacular: an annual parade involving many of the community's tractors in their various makes, models and stages of corrosion. More than 40 of the humble farm vehicles are decorated like themed floats. One of them has a driver wearing a Donald Trump mask with a gang of "Mexicans" on the rear platform, confined behind a "wall" constructed from a wooden pallet.

The Trump tractor evokes a reluctant and foreign feeling of badness - like the recollection of an unpleasant dream - which is quickly forgotten as tractors with more benign themes roll into view. The recent death of Carrie Fisher has apparently inspired several Star Wars-themed entries. The vehicles - which, to the uninitiated, basically look like inefficient factories on comically large wheels - are indiscriminately pelted with water balloons by roadside kids, while their parents watch from deckchairs and drink bubbles.

And then: "Elvis in the Bay;" a one-night performance by Andy Stankovich (2015 Male Artist of the Year, Variety Artists Club NZ), who is without question the best Elvis impersonator this side of the Brynderwyns, having (according to Bay folklore) played in Vegas with The King's original band. Stankovich takes over a reserve by the beach and plays to a dwindling crowd of adults in deckchairs, asking a gold coin koha for the local St John's ambulance service (which has dispatched two officers to collect said koha, who are momentarily absent from said performance to inspect the arm of a boy who fell off our fence while playing gang tiggy; arm not broken).

And then: A Scrub Fire, which sends thick smoke cauliflowering across the extreme southern end of the Bay's main road. I ride down with Lennie sitting on the handlebars and we see fire crews hosing a swarm of angry red flames on the other side of the estuary; eating the native bush on the hills that extend out to form a headland in booming silos of grey rock. Onlookers arrive to watch the spectacle on bicycles and tractors and quad bikes, some of them openly drinking. The fire is happening exactly at dinnertime, which gives the crowd a mood of torn impatience. Two helicopters use monsoon buckets to put it out, flying back and forth from the sea. Pedalling back to The Camp, we pass an old man in a deckchair with a Lion Red; pensively contemplating the smoke from safe distance.

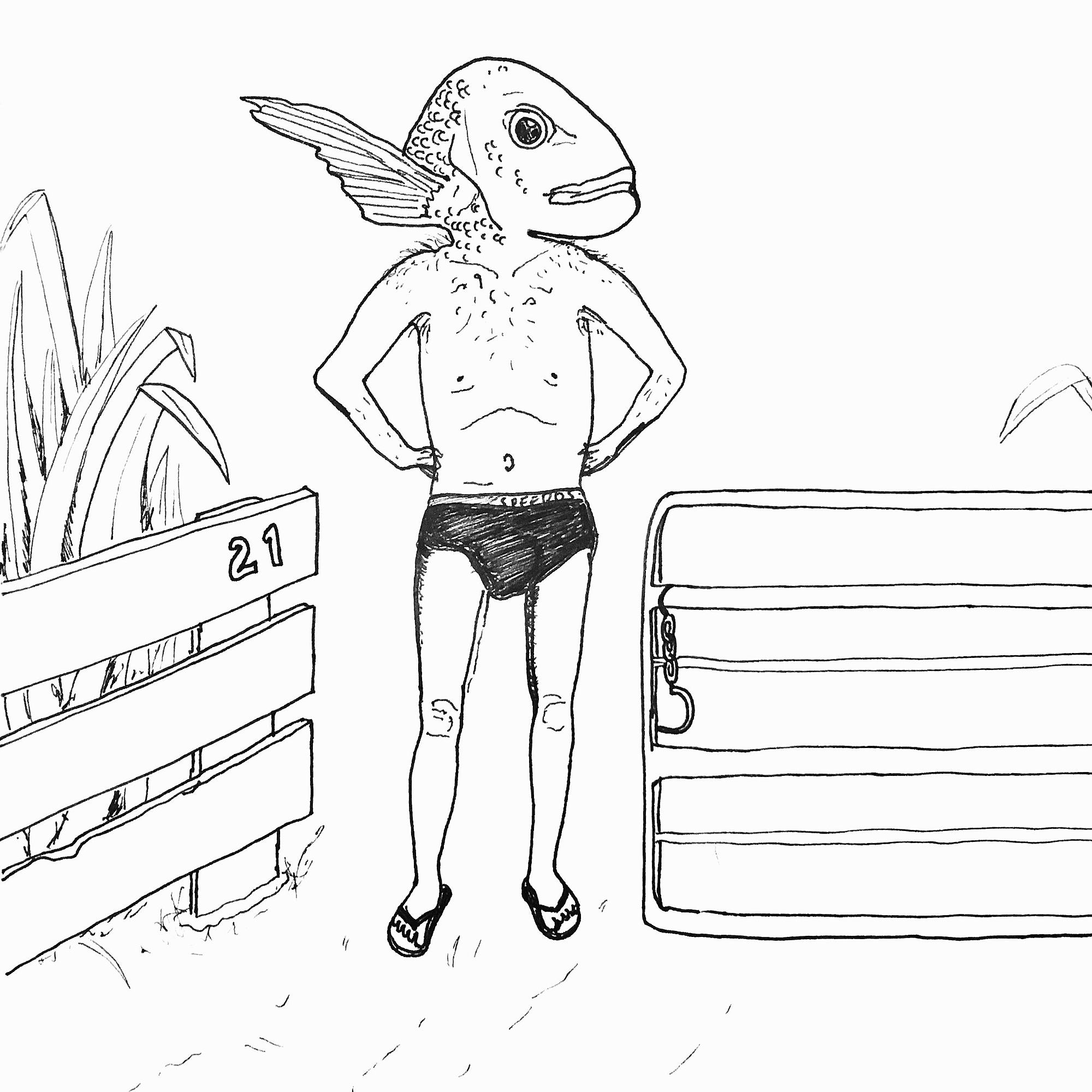

Living next-door is a man they call The Fish: so-named because he is apparently a former champion freediver, and these days, although probably aged in his late 60s, he keeps fit by swimming laps of The Bay in black speedos. The Fish has a hairy triangular back and long, simian arms. His skin is Hasselhoff-orange, and his smile reveals a set of incongruously pristine teeth. In the evenings people gather on the beach to watch him swim out his surfcasting line; bobbing out to sea like a great hairy turtle; with a baited hook (according to Bay folklore) clenched between his teeth; and all this at shark feeding time.

The Fish's regular ocean forays make him a constant feature of the human foot traffic in the pohutukawa reserve; employing a slow, arm-swinging walk to cross the bone-yellow grass.

One morning Sister Tess emerges from an outdoor shower wearing only a towel and stops to give Brother Mitchell a peck on the cheek, just as the Fish is passing The Camp. And The Fish, witnessing this affectionate exchange between ST and BM, and clearly moved by the lingering euphoria of New Year's Day - the ambiguous social temperature which results in a temporary anarchy of public day-drinking and music-playing - then asks Sister Tess if he can "have one of those”. ST, confused, bewildered and reluctant, but acting under all the undue pressures of an ambush, goes over to him in her towel, kisses her hand and plants it on his face.

I emerge from the house to witness the tail-end of this interaction (having just dropped a sulphuric bomb, the result of a lengthy gestation of protein and whiskey): ST's hand pulling away from The Fishs' face to reveal a brilliant white grin; and I mistakenly believe that she is replacing his false teeth after they fell out of his head. I don't know otherwise until later that night, when ST recounts the incident with polite restraint.

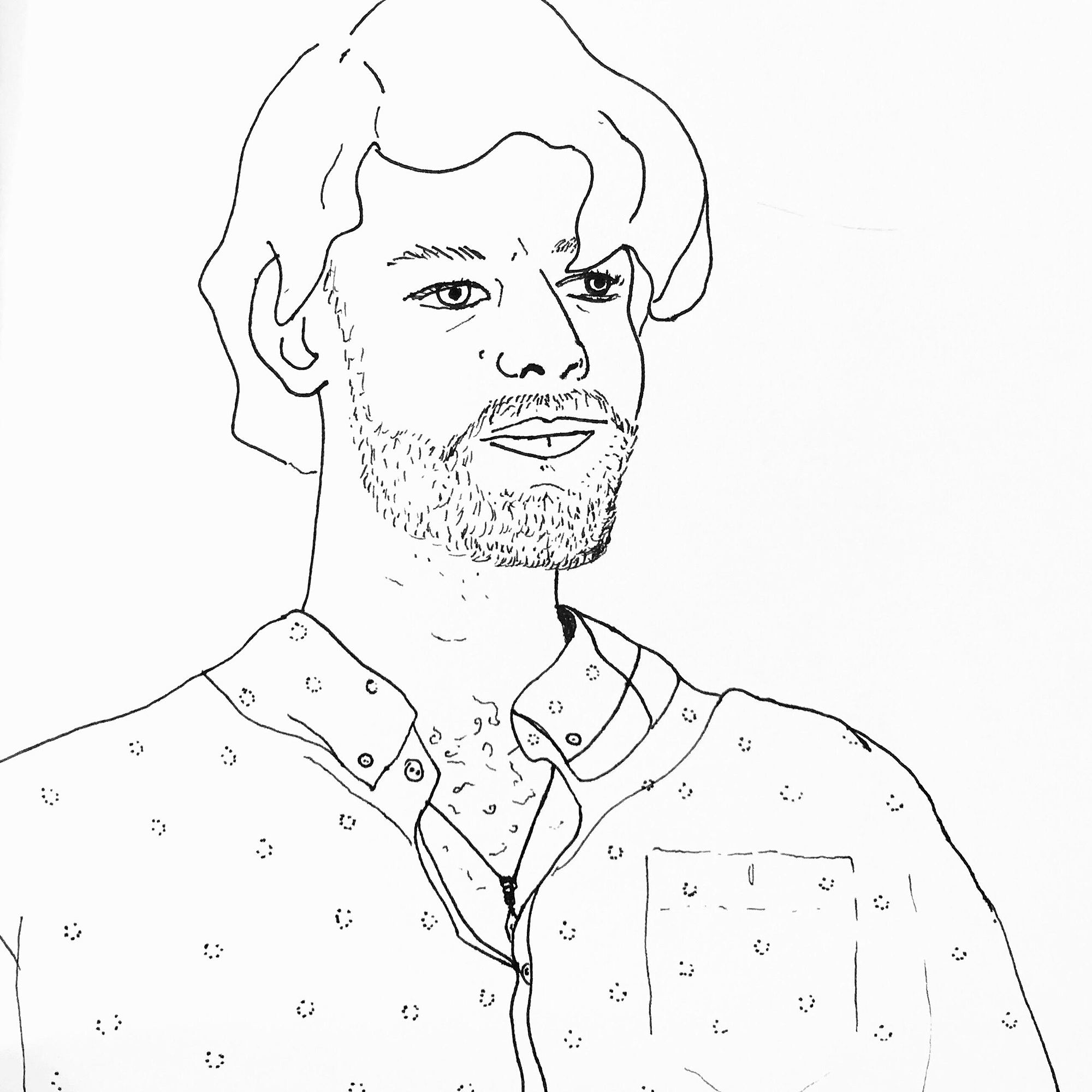

Around this time I'm particularly aware of my father's movements and the subtler aspects of his being; as we attempt, in close quarters, to navigate that father-son-mutual-envy which is at once fiercely loving and intricately resentful. I've noticed, for example, that his resting facial expression is a pained grimace. And that he has an inexplicable taste I’d never picked up on for percussive lounge music - the kind that plays in trendy fusion restaurants.

My father continually reminds us that he's acquired for the summer, from what sounds like a dubious Chinese wholesaler, the "fireworks from hell." He is in his element up here. The place enhances his mana. He patrols The Camp in a big fading surf T Shirt, which always looks slightly damp. He's always busy; tinkering with the rods protruding from his fishing kayak; standing with arms akimbo in the p. reserve and exchanging truisms with other beach-watchers; knocking on the concrete water tank and listening for the echo with the kind of rapt attention that suggests the waters within are whispering eternal horrors he can't quite hear.

He is gradually distributing vacuum-sealed hunks of smoked marlin to friends and acquaintances around The Bay (he landed a big one this Summer; 256.5kg). Fish, especially crayfish, are a currency of goodwill here, and my father is a keen and fruitful trader. He's drinking an Export Gold; drawing hard on a menthol cigarette; making repairs to the tent which is set up in the backyard and periodically occupied by visiting couples, evening nappers or a single chirruping cicada.

We go north. We stop at a deep-blue lake with a beach of powdery white sand that's almost the consistency of dust. I'm not certain whether the sand has been trucked in or not. The beach is packed with families with lots of young kids. These are not Sea People, but Lake People. They don't so much swim as walk around in the shallows, absent-mindedly lobbing balls and Vortexes at each other among the anchored boats, and patting their bodies down with handfuls of water. I hear a man saying to another man that two people have drowned here this summer. The contrast of the jewel water and white sand with the arid, pine-studded landscape gives the scene the feel of a post-apocalyptic-watering-hole.

I go into the water mainly to pee; and I'm aware that the many children floating around me on pool toys are also probably peeing; and that we're in a body of rainwater with no inlets or outlets. I don't pee near the children. I wade across the corrugated sand until the crescent of clear water drops off suddenly into a blue void and the temperature goes from urinary warm to ice cold. No one else is swimming out here. When I kick off from the edge of the shallows I notice the water is far less buoyant than salt water; it sort of wants to pull you down.

We go north. In the vast back-country of the Kauri Coast is another weird tropical oasis; this one takes the form of a nostalgic hotel. It sits on the Hokianga; a deck teeming with palm fronds looks across the water at the giant yellow dunes framing the harbour's entrance, into which the sun melts perfectly at dusk. Flanking the deck are lawns sloping down to a stony beach and a jetty off which locals are either fishing or doing manu bombs. The hotel's corridors have a dim colonial vibe. It gets its staff from the tiny surrounding settlements ("are youse finished with your meals?") and “Lady Love” (from Lou Rawls' 1977 album When You've Heard Lou, You've Heard It All) plays from a ubiquitous and cleverly hidden outdoor speaker system.

Lady love, I heard a voice and it soothed me / Lady love, a simple tune and it moved me...

The hotel initially comes across as being in that special club of places where it is totally acceptable - even encouraged - to drink a Piña Colada - until the sinking dread on the bartender's face reveals he hasn't made one in years. But the Piña Colada, as far as drinks go, still seems to capture the essence of the estab; as does the hopeless but strangely affecting ‘Lady Love’.

Lady love, the man's a fool to be leaving / Dreams of love, passing by like the seasons...

The first time we stayed here, we found congealed blood stains on our sheets. But the staff's reaction to this (genuine, traumatised remorse: long-winded apologies from the manager and head maid, the whole stay and breakfast free of charge), coupled with the endearing singularity of the place, has brought us back again; maybe not for the last time. Forget the blood on the sheets.

We go north. We get a burger and a chocolate thickshake somewhere east of Kaitaia. We take the Far North Road past New Zealand's Northernmost Motel, which is sporting a palm-tree emblazoned, pastel-coloured sign from the 70s. The towns are tiny and rural and quiet. Homemade Pickle Jam. Septic Tank Cleaners: Call 0800 SMELLY. NZ's Kumara Capital. Flounder (The World's Best!) Did Ya Get Ya Kumara? Spray Free Avo's. We pass benign little churches and the skeletons of burnt-out cars, and farm shacks with rusted roofs that look ready to be used in a Fire Service drill.

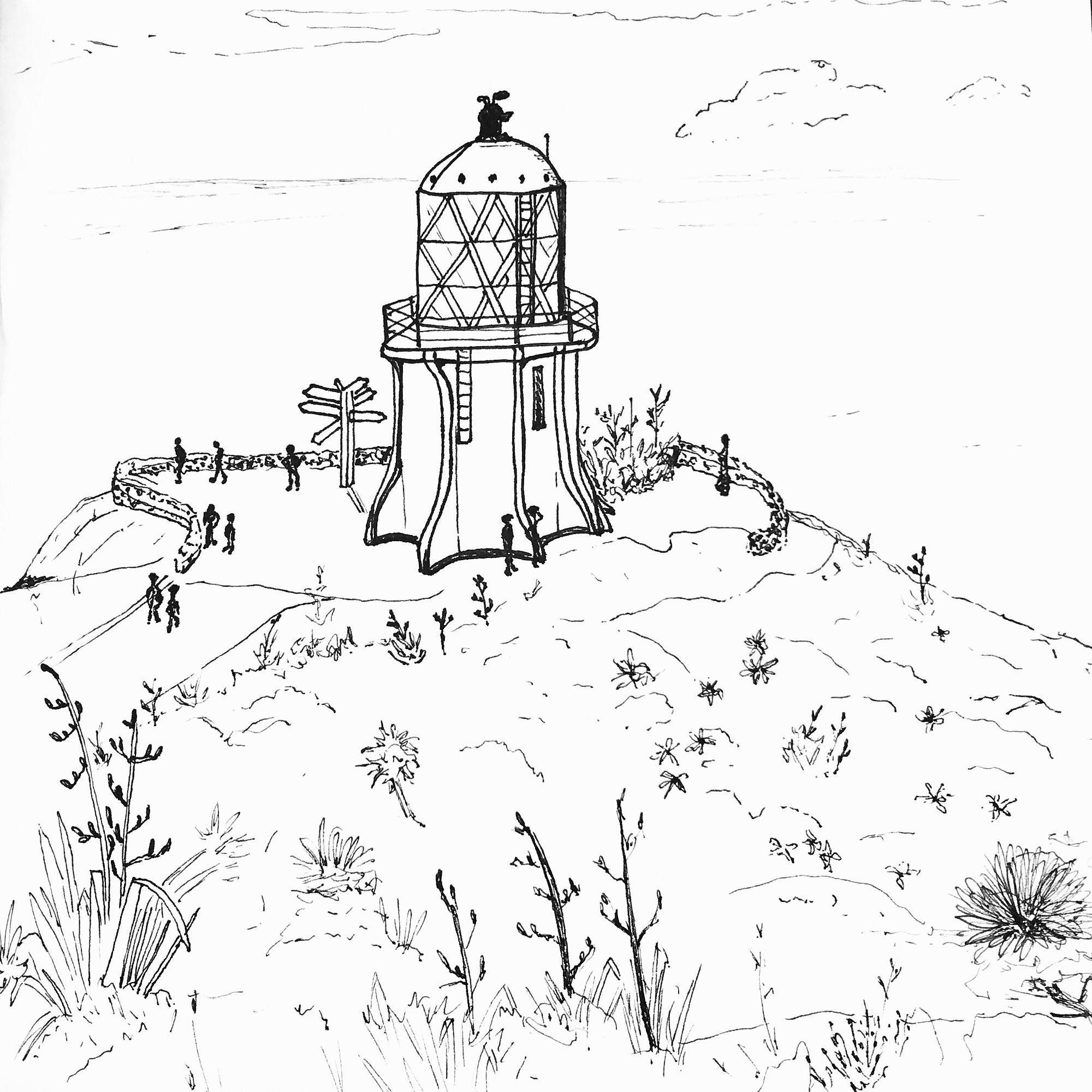

The Cape is not the satisfying full-stop to the country's geography its busloads of visitors are probably expecting. It's more like an eerie dropping-out mid-thought. The land goes on an eccentric tangent before it falls into the sea. Originally an island adrift from the mainland, now traversable thanks to massive sand deposits, its red volcanic rock is Martian in appearance, much frequented by tourists and pilgrims and yet deeply unfamiliar; with the ominous, ego-crushing silence of a desert.

The land is so harsh that the flax, Manuka and cabbage trees which cover its final rolling expanse only ever reach bonsai-size. At the northwestern-most point is a flinty wedge of rock, pummelled on both sides by reams of swell from two different oceans. Marooned there, looking puny and trapped on the brink of annihilation, is an ancient, flowerless pohutukawa tree, through which all Māori spirits descend into the underworld, sliding down a root into the foaming waters.