Perishable Histories: Reflections on Pigs and Poison

How do we make art about difficult histories? Kerry Ann Lee responds to Candice Lin's Pigs and Poison at Govett-Brewster Art Gallery.

Turn us to ashes

Reduce us to dust

We cannot perish

Fast enough

— Cattle Decapitation, ‘Plagueborne’, 2015

The origin of the Black Death was rumoured to have been started by Mongol hordes, who flung diseased corpses over the ancient walled city of Kaffa in 1346. In present-day New Plymouth, the walls of the Govett-Brewster are repeatedly blasted by crude bombs made of oil, wax, lard and bone-black pigment, launched from a human-sized trebuchet (medieval catapult). This is Pigs and Poison, a survey exhibition of recent and new work by Los Angeles-based artist Candice Lin. Over the past decade, Lin has researched material linkages between nature and culture to radically interrogate colonial narratives and histories of migration. In a studio interview, she discusses how contamination and virality are racialised to inform public understandings of disease and undesirable others.

Pigs and Poison connects Chinese indentured ‘coolie’ labourers with the cultivation of crops like tobacco, sugar cane, poppy and fungus in the Americas during the 19th century. The title refers to the opium trade and Chinese workers who were pejoratively called ‘pigs’ due to their queue, or long braided pigtail. Lin works with an extensive list of materials, ranging from plant, animal and synthetic-based fibres. Plant matter integral to indentured labourer narratives – yucca, cotton pulp, poppy stems and indigo form a Map to an Unknown Sea (2018). Beneath this, a curious lump of flesh on the floor (made from encaustic wax, resin, wire, paint and fibreglass) purrs softly upon closer inspection. The spillage of volatile legacies is translated through a vast array of painting, sculpture, textile design, VR, drawing and installations presented across several galleries of the museum.

Candice Lin, A Robot Spoke What My Father Wrote (2019).

Difficult histories connect us like viruses. Candice Lin and I are both artists, born in the same year on opposite sites of the Pacific Ocean. Having previously worked with my father’s memories and dreams (The Bay Hill Times Gazette and Return to Skyland) I was interested in Lin’s installation A Robot Spoke What My Father Wrote (2019). The towering razor-wire-capped barricade greets viewers upon entry, introducing themes of obstruction, racialised language and cultural loss through assimilation. Lin examines a quote by American philosopher John Searle, who once referred to Chinese text as ‘meaningless squiggles’. She questions this through online translation and collaboration with her father to alter the words from English to Mandarin characters, and chisels these out of the drywall like giant robot graffiti. According to critic Lucy Lippard, the fence remains the most obvious symbol of exclusion, control and the myth of the Western frontier. This boundary narrative endures in the extremity of Trump’s US–Mexico border wall.

Pigs and Poison is a befitting spectacle for our Covid times, meditating on the enduring legacy of racism and xenophobia long before the so-called ‘Chinese virus’ hit the scene. Lin highlights popular anxieties of plague and contagion and their influence on US immigration policies to this day. For instance, early documented use of the term ‘Illegal Alien’ implicated Chinese coolie labourers. Scholar Anssi Paasi suggests that, in controlling corporeal and national borders, “since the late 19th century, the State has been understood as an organism, in the spirit of the emerging evolutionism with boundaries as its membranes.” Artist Allan Sekula posits that the idea of the ‘social body’ emerged through the use of early photography as a mechanism of criminal surveillance. Three paintings in the show illustrate this by referencing a forensic anthropology study in the Undocumented Migration Project– tracking the decaying of pig bodies (used as surrogate humans) in the desert at the US–Mexico border.

Candice Lin, In my memory it is raining inside my father’s house (Solaris), (2020).

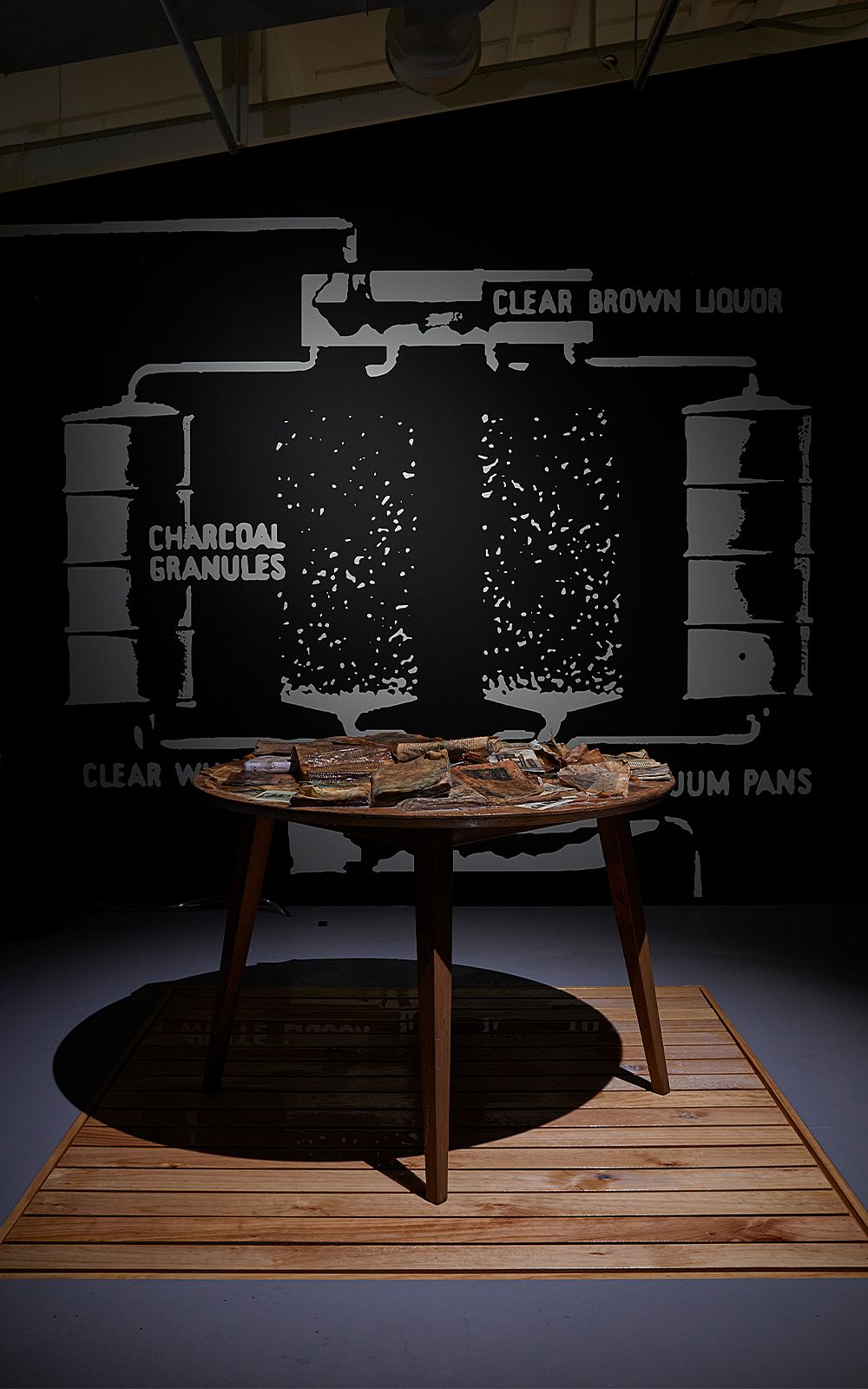

This decomposition strategy is both macabre and mechanised. Within a small internal room, we encounter In my memory it is raining inside my father’s house (Solaris), 2020. A table bears the weight of old books containing unreconciled histories of early Chinese migration and labour. These texts are gradually ruined by an eternal drip of water, in homage to a scene in Tarkovsky’s 1973 film Solaris. Another purring flesh lump greets us at the door and the significance of these is understood here, viewed alongside a diagram of an industrial filtration process on the wall. This alludes to the plight of Chinese labourers in Cuba, about whom Lin uncovered a testimonial asserting that bones of deceased workers were ground into ash to whiten sugar. Difficult histories are compelling and complex for artists like Lin to translate, both as an insider, and sometimes as an outsider to other people’s histories. These grim stories are reminiscent of work by artist Jasmine Togo-Brisby, a fourth-generation Australian South Sea Islander who has explored the Pacific slave trade, including its implication in sugar manufacturing.

The whakapapa of perishable goods spans many generations. In an email exchange, historian Nigel Murphy reminds me that, “Not all Chinese labourers were coolies!” and this is true. Our family legacy of migration is retold in my father’s oral history. My great-grandfather worked in the sugar plantations in Cuba and his bones were not used to filter American sugar; rather, he lived out his days as a free migrant in a village in rural Canton, China. My father, Colin Lee, recalls the first time he encountered pasta, via care packages sent by his grandparents in Dunedin. He had to “chase a bread roll around a plate” on his first BOAC flight, emigrating to New Zealand as a boy in the early 1960s, later becoming a chef, cooking both Chinese and European cuisine at restaurants and hotels.

Yet ingredients were once hard to come by. Contraband even. In 1978, restaurateur Kenneth Chan testified in a secret New Zealand Supreme Court hearing concerning trade licenses for importing Chinese foodstuffs: “Your honour, time marches on. Our eating habits have changed through travelling and you’ll find a variety of things that are kept in kitchen cupboards … I’m sure within these walls here we want a change – we don’t want to have stew every day!”1 The New Zealand TV series Border Control (2004–)depicts Asians as criminals trying to pull a shifty to sneak dried foodstuffs through airport security. This was noted in the book Old Asian, New Asian, by author K. Emma Ng, whose friend in Chengdu expressed shock at a reality TV show “dedicated to shaming and laughing at Chinese people”.

It seems fitting that Lin’s show premieres in New Plymouth, Taranaki, which was home to butter merchant and fungus exporter Chew Chong (c. 1828–1920). According to historian Dr James Ng, very little rice actually came from China in those early days. Similarly the opium consumed in New Zealand came from Britain and her colonies, chiefly Australia. As a counterpoint, the New Zealand fungus trade of mook-ngee or wood ear fungus (a.k.a. ‘Taranaki wool’) flourished and was mostly handled by Chinese.

Candice Lin, Papaver rohoeas (2020). Image: Kerry Ann Lee.

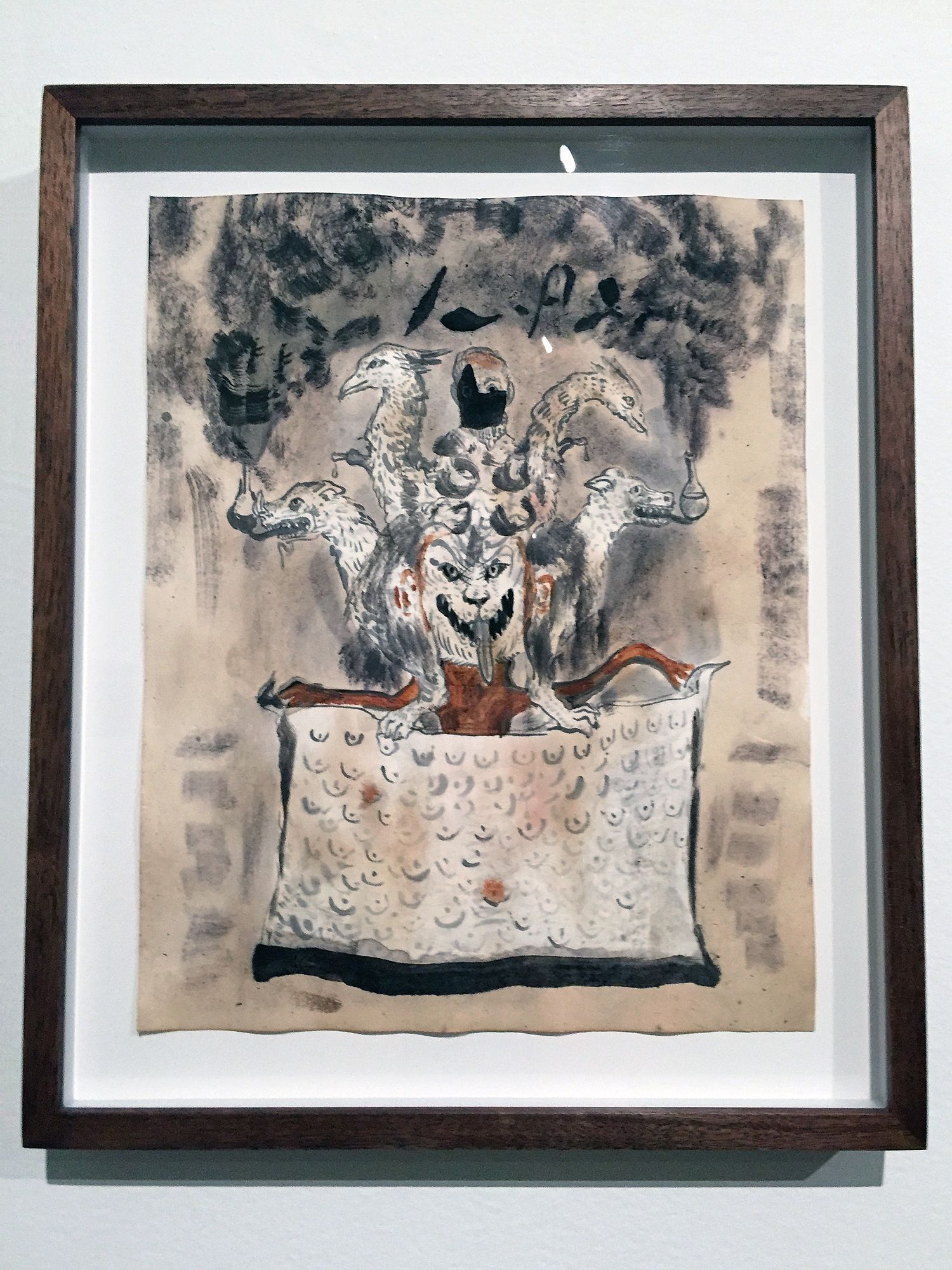

Candice Lin was spared the embarrassment of exposure to shows like Border Patrol. Growing up without a television, she instead immersed herself in 17th–19th-century literature, which is evident in her aesthetics and approach. My favourite of her works are small drawings that she did while under the influence of a tincture of plant materials (opium, tobacco, alcohol and tea) that she brewed and ingested in an attempt to reveal untold histories of traded goods. Lin followed medieval recipes, including making drawing inks from crushed oak galls (swollen growths on oak trees formed by nesting wasps).

Pigs and Poison is full of extremes. Two figurative Witnesses stand silent, visibly clad in iron-muzzled masks (influenced by African ‘slave bits’ and medieval scolds’ bridles for outspoken women) and garb adorned with patterns from Candice’s dreams. These sculptures are purposefully confronting. Lin’s practice explores centuries of global slavery through imagery, materials and racialised stereotypes, which, read at face value in the current context of Black Lives Matter, could run the risk of co-option and verge on being unsafe. However, she implicates herself as an Asian–American working with African slave histories. Not to glorify slavery or misogyny but to find linkages and bring these closer to Chinese and Asian diasporic histories in the margins. Herein lies the challenge for art makers working with legacies that are not their own.

Virtual role-play offers an interactive method with which to encounter other histories. You can even don a mask and cloak with a built-in VR headset to become a plague doctor. Inside Lin’s cyberworld, pulsating flesh lumps are lobbed at you from the trebuchet while shadows of racialised cartoon coolies scurry away in the periphery (this was suspended, but on display during Level 2 restrictions). There are paintings of San Francisco and Honolulu Chinatowns at the turn of the 20th century, when bubonic plague broke out and these neighborhoods were set on fire. The rumour of Chinese eating rats as the cause for the outbreak mirrors current sensationalism of Chinese appetites for exotic animals like bats and pangolins.

Candice Lin, Witness (Blue Version), (2019)

Candice Lin, Vermin Visionary, (2020)

My own research into Chinese in the Americas has lead me to similarly distressing tales, like the 1911 massacre of over 300 Chinese in Torreón, Mexico, and San José Chinatown, which was burnt to the ground in 1887. Here in Aotearoa, anti-Chinese discrimination occurred in the form of legislation like the £100 Poll Tax, imposed exclusively on Chinese upon entering the country from 1881 to 1944 (that’s $20,000 in today’s money) and the ‘Alien’ non-citizen status between 1908 and 1951. Manying Ip and Nigel Murphy’s book Aliens At My Table: Asians as New Zealanders See Them (2005) is a hefty tome of racist political cartoons published in New Zealand since the late 19th century, depicting Chinese literally as grotesque ‘alien others’, ‘Yellow Peril’ octopuses and lecherous monsters — tropes also commonly deployed in the US, Canada and Australia.

We are still trying to reconcile the burden of these legacies. In Wellington, retired gold miner Joe Kum Yung was murdered in Haining Street in 1905 by a white nationalist, while Alison Wong’s award-winning novel As the Earth Turns Silver (2009) is based on the brutal killing of her great-grandfather, a Chinese immigrant, in Wellington in the 1920s. There is also Kim Lee, a Newtown greengrocer who was reprimanded for opium possession and detained on suspicion of having leprosy. His shop on Adelaide Road was fumigated, and his fruit, vegetables and personal possessions removed and destroyed. He was sent to ‘quarantine’ in a cave on Mokopuna Island where he died nine months later of heart failure, in early 1904. Kim Lee’s tale is told through a documentary by Matilda Boese-Wong, and a harrowing sound performance by artist Mike Ting, exploring the psychological wreckage of his life in exile.

Candice Lin, A History of Future Contagion (2020)

Lin’s practice exposes discomfort in migrant histories, edging on the absurd. A history of future contagion (2020) is a dark and glorious centrepiece to her show. The work commands sizeable gallery real estate, with the trebuchet firing twice daily (at 11am and 2pm). Watching the bombs smash against the wall to make the giant splatter painting is cathartic. Lin’s temporary monument to a dubious history facilitates a durational assault, posing a perfect aesthetic challenge to Len Lye’s sleek kinesthetic sculptures also housed in the building. A lot went on behind the scenes. Lin collaborated with the Govett-Brewster to produce this exhibition entirely remotely, with the gallery following her instructions to construct the trebuchet and cannonballs from scratch. Due to our cooler climate, the projectiles bounced off the wall more than they would in California, hence they were microwaved before deploying.

Lin’s frame of reference for Pigs and Poison brings to light the precarious nature of Asian identities right now. Gallery staff reported that the show drew welcome reflection and discussion from their visitors. Chinese and Asians are still dangerously misrepresented in media and are vulnerable to racism and hate crimes, which have escalated this year with Covid-19. In a recent online discussion hosted by Queens College, New York, Professor John Chin from Hunter College says, “To embrace an Asian–American identity is to acknowledge racism.”

Candice Lin, A Robot Spoke What My Father Wrote (2019)

As part of the public programme organised by Assistant Curator Elaine Shen Rollins, artists Angela Kilford and Julia Hope hosted a natural dyes workshop at the gallery, while I presented alongside Dr David Mayeda and Professor Manying Ip in Words as Weapons: When Racism Divides Us, a panel and workshop weekend that foregrounded the issues audiences encountered through Lin’s artwork. As I was a newbie to the city, Elaine introduced me to New Plymouth through some promotional local radio spots. I remembered the backlash on talkback radio in 2016 against then mayor Andrew Judd, a Pākehā who spoke out against the racism he faced in attempting to increase Māori representation on local council. In 2020, however, DJ Dave from Most FM was reassuring, admitting his own reckoning with racism live on air with us, and acknowledging the value of these public talks.

Pigs and Poison is a grand, romantic, ambitious, non-vegan codex with multiple reference points. Lin is a generous researcher, making available her source materials through publications in the gallery reading room, as well as a video of her in her studio and a virtual tour of the show, both available online. Now that we have this wellspring of knowledge, what shall we do with it? What are the responsibilities of working with cultural historical materials that may or may not be ours? And how might such concerns apply to those whose core business is to share facts and tell stories? Lin tests the limits of the artist as author, translator and historical subject, transforming materials to draw far-reaching connections in these precarious times.

1 Ken Chan, Henry Kwing and Esther Lee, in a recorded interview with the author, 19 November 2007, Wellington.

Pigs and Poison

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

8 August - 15 November 2020

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

Feature image: Kerry Ann Lee. All other images by Sam Hartnett unless otherwise stated.