Translating the Zeitgeist: A Review of 'Politics of Sharing – On Collective Wisdom'

Matthew Crookes examines 'Politics of Sharing', an exhibition from the Asia-Pacific region in Berlin.

Matthew Crookes examines Politics of Sharing, an exhibition from the Asia-Pacific region in Berlin.

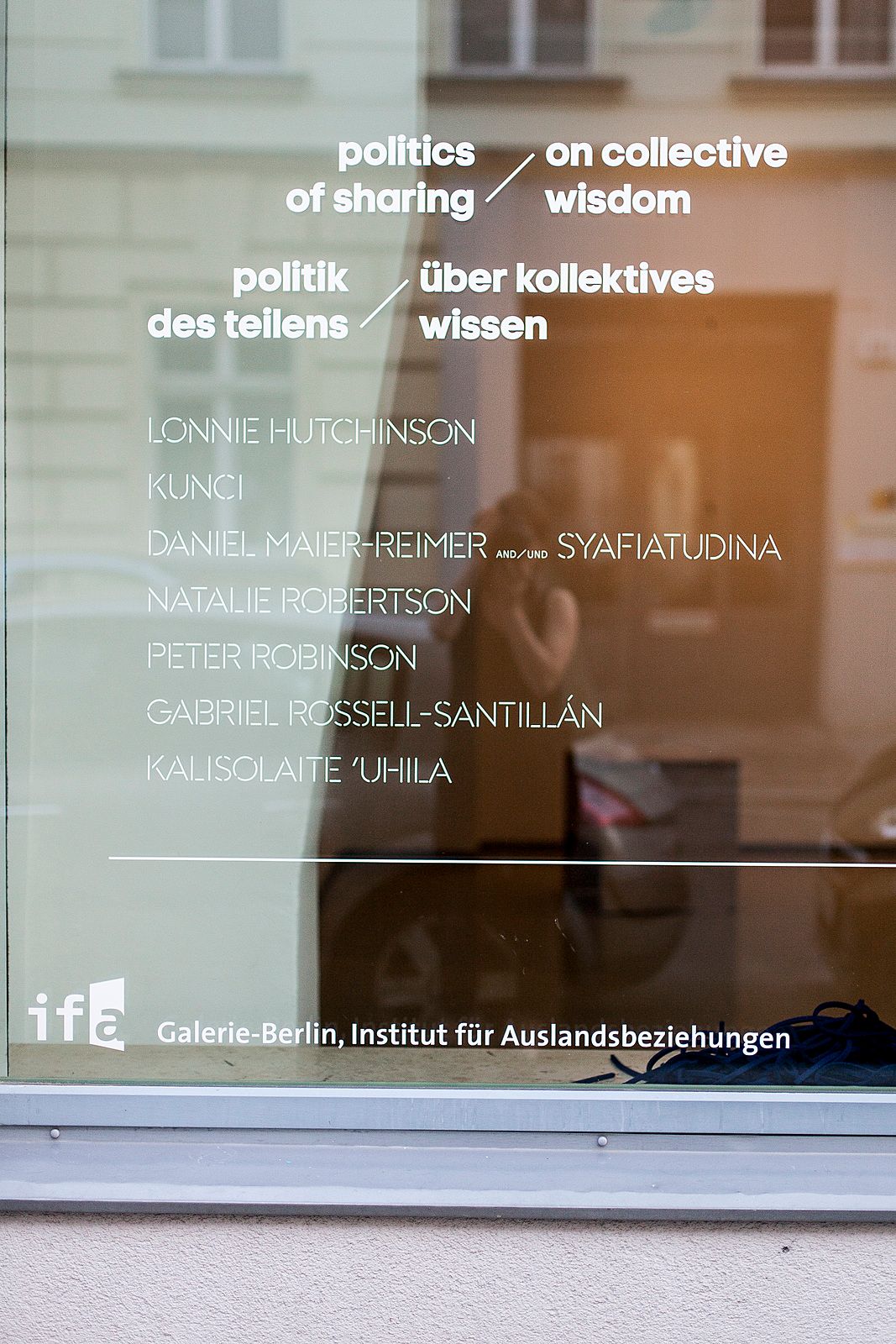

Co-produced by Artspace in Auckland, Politics of Sharing – On Collective Wisdom is a group show at the ifa-Galerie Berlin, in the heart of the city’s Mitte district. The ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen, or Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations) describes the exhibition as “bring[ing] together artistic and social positions from the Pacific Region with European perspectives, projecting manifold points of views on ‘numpang’, the Indonesian culture and politics of sharing”. The exhibiting artists are Lonnie Hutchinson, Daniel Maier-Reimer and Syafiatudina, Natalie Robertson, Peter Robinson, Gabriel Rossell-Santillán, and Kalisolaite ʻUhila, together with artists representing the ongoing sociological project Radio KUNCI.

As well as being a straightforward art exhibition, Politics of Sharing presents the outcomes of a multidisciplinary academic study and research project. As such, it is in keeping with the ifa’s tradition of presenting collaborative, multi-disciplinary shows from non-European and non-Western regions, with substantial bodies of other material sitting alongside the public exhibitions. Evident here is the demand of the institution to present a case (a study, research) that provides some object lessons in the outcomes of the frequent conflation of ‘research’ with ‘artistic practice’ – as if the two terms were interchangeable.

But not all research is art and not all art is research, and the two things are received quite differently. Coupling a hefty body of meaning to a collection of artworks might satisfy institutional demands, fulfil the brief, but it does not ultimately impact how we look at the work in the space (or, for that matter, on the website). In such presentations, the full extent of the research and cumulative body of material can usually only be hinted at; for example, lengthy sequences of audio visual material really depend on the casual visitor’s available time and commitment to remaining with the work.

Coupling a hefty body of meaning to a collection of artworks might satisfy institutional demands, fulfil the brief, but it does not ultimately impact how we look at the work in the space.

The works of Hutchinson and Robinson take centre stage and dominate the show, whereas the video pieces are shuffled away in corners and dark little nooks. Robinson’s cut-out felt lines and nodes, Syntax Systems (2015), are spread throughout the space. There is a looseness to the pieces, some of them vividly coloured, all following a similar graphological pattern. They are variously draped and arranged around the other works, contrasting their more formal and conventional display. Hutchinson’s hanging installation, Time of Darkness, Time of Light, creates a kind of demarcation between the front and rear spaces. (The back of the ifa gallery is often reserved for sound and video works and as a space has quite an intimate feel.)

Radio KUNCI is represented by a sound work, a series of podcast conversations that you are invited to sit down and listen to. These were recorded during the first four weeks of the show – when, as the ifa’s website enthuses, “the gallery was turned into a radio station”. In the exhibition, they are accessible via headphones around a table, but they are also available online. I suspect the overwhelming majority of visitors will, as I did, come to them later on. There are moments of direct engagement, like the collaborative booklet by Maier-Reimer and Syafiatudina, containing letters and short essays, which is offered on a wooden pallet as something to take away, in the manner of Félix González-Torres.

The obvious question is whether this manages to be more than an art exhibition with some other stuff tacked on. The presentation raises some questions here. As you might reasonably expect, the headlining artists are in the main space, and very visible. However, in quite stark contrast, contributors with lower profiles outside their own regions are tucked away in corners; for example, Radio KUNCI is represented in a smaller space by the front window. Robinson’s pieces appear to aim for a kind of unification, drawing attention to some of the lesser-knowns. Indeed, they act as a sort of connecting motif throughout the show. But they are alone in functioning in this way, and the display remains rather uneven.

The organisers’ evident enthusiasm for their project may not be as easy to pass onto members of Berlin’s regular gallery crowd, unless they happen to have personal connections either with the region or with the participants. You are certainly invited to take your time over the show. But there are some awkward moments here too. Whereas each of the four Radio KUNCI recordings is given its own set of headphones, allowing several visitors to listen at the same time, the artists of Imaginary Date Line have been clustered together, relegated to an obscure corner in the smaller room, such that there are several video artists whose work can only be experienced on one screen.

While this show’s ambitions don’t quite extend to an attempt to change cultures, it is certainly part of a wider trend looking at issues around collective authorship, activism, and ‘soft power’.

The show’s accompanying text veers towards the poetic: “As we look at the same sky we literally share the same air … The complexities of the human condition are explained through the multitude of their offspring.” The artists may have been working with common themes, but to suggest that this conveys a coherent agenda or study may be over-extending what an art show can realistically do. One could equally argue that such an endeavour is better expressed as a publication or documentary. How useful is it – at least for a local Berlin audience – to view this exhibition as a reflection of a set of sociological and geopolitical concerns, or, better, as a glimpse of a cross section of Pacific and South-East Asian artists?

Open sourcing and grassroots activism are once again coming to the fore at a time when government has had some spectacular fails. In Europe, people are crying out for leadership and direction, which goes some way towards accounting for the appeal of the far right. With the increasing impotence of established institutions, many others may well turn to self-help as a solution to their problems. While this show’s ambitions don’t quite extend to an attempt to change cultures, it is certainly part of a wider trend looking at issues around collective authorship, activism, and ‘soft power’.

It is perhaps here that the project has most to offer. In contrast to the Berlin Biennale, whose sarcastic, disengaged tone has attracted harsh criticism in the present climate of geopolitical and environmental uncertainty, Politics of Sharing could yet prove to be closer to the true zeitgeist.