A Wall in Need of Painting, Artists in Need of Payment

The conversation around the value of art is worth having, so why can't we have it?

The conversation around the value of art is worth having, so why can't we have it?

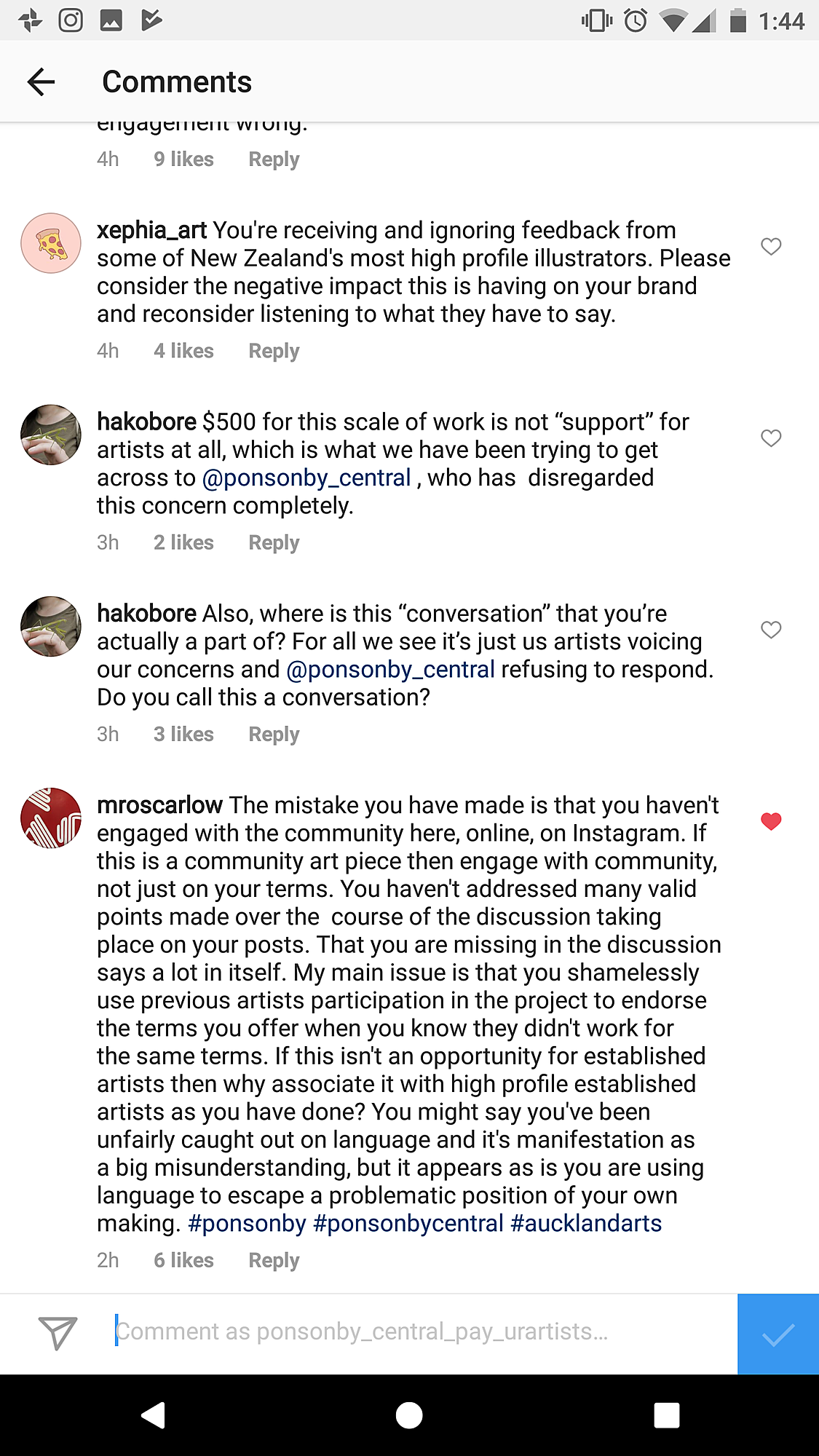

On the 30th of October, Ponsonby Central announced their Summer Art Mural Competition on Instagram. The competition was unremarkable – another social media stunt offering a small prize. However, the backlash Ponsonby Central received via the comments section on their post was remarkable – until it disappeared entirely after every dissenting comment and follower was removed by Ponsonby Central’s marketing team. For something so apparently minor, why was so much at stake?

The light tone promoting the competition – “Yuss! It’s that time of year again...” – soon began to read like resilient propaganda when compared to the onslaught of criticism surrounding the competition and vehement requests that Ponsonby Central address the ethical issues being raised by their would-be artists.

As Sloane Kim (an illustrator and prominent commenter on the competition’s social media) has discussed in their in-depth feature exploring the history of the competition and detailing the fall-out, the problem emerged when Ponsonby Central offered a meagre $500 cash and $500 materials contribution – and escalated when they reacted to their followers’ critique in such an antagonistic way. I met with Kim and another commenter, Ross Liew, an artist, teacher, co-founder of the Cut Collective and chair of Auckland City Council’s Advisory Panel for Art in Public Places. As we talked about the competition, I realised this issue went far beyond Ponsonby Central. This was just one example among many, illustrating the practices that enable the exploitation of artists, and which perpetuate the chronic undervaluing of the arts in New Zealand.

One of the foundational problems of the Ponsonby Central competition was its use of the speculative work model – a model that is present in most creative industries but a particular “hallmark” of the design industry, says Liew. No!Spec, an organisation promoting the practice of refusing to work within spec-based models, defines spec work as:

Any kind of creative work, either partial or completed, submitted by designers to prospective clients before designers secure both their work and equitable fees. Under these conditions, designers will often be asked to submit work in the guise of a contest or an entry exam on existing jobs as a ‘test’ of their skill. In addition, designers normally lose all rights to their creative work because they failed to protect themselves with a contract or agreement. The clients often use this freely-gained work as they see fit without fear of legal repercussion.

“Spec work is really common, but not many people are aware of it or address it. A lot of it is dressed up as community projects,” says Kim. Liew distinguishes spec work from community work, which he does at a minimal or no fee. The weekend before we talked, he had painted a wall bigger than the Ponsonby Central one for free. He has painted this wall, in a local fruit store, for ten years – all he takes home after the work is a bag of fruit. Liew has a long term relationship and understanding with the store’s owners. Ponsonby Central, on the other hand, does not have any kind of neighbourly relationship with the competition winner. It is also owned by one of New Zealand’s biggest property developers, which suggests they are fully able to offer adequate payment for the work, but choose not to. Furthermore, the work cannot be understood to benefit the local community either, given that it requires the inclusion of hashtags about Ponsonby Central and an interactive social media element, essentially rendering it an (albeit attractive) form of advertising.

Ponsonby Central does not have any kind of neighbourly relationship with the competition winner. It is also owned by one of New Zealand’s biggest property developers, which suggests they are fully able to offer adequate payment for the work, but choose not to

The spec work model is not confined to the design world – it also exists in the standard gallery ‘call for proposals’. Every year, gallery spaces throughout the country ask artists to make proposals for their space, usually requiring them to refrain from submitting a proposal sent to another gallery or organisation. Artists who submit successful proposals are only sometimes reimbursed with a fee to assist with production, materials and transport of the work. If the artists do not live in the same city as the gallery, they are often asked to organise their own airfares, accommodation and any additional freight costs. Spaces exist on the artists’ work, while artists often comes out at a financial loss, having only gained “exposure”. In project or artist run spaces, where money is scarce, the space is limited in what it can provide the artist. But larger galleries or commercial enterprises like Ponsonby Central cannot hide behind the same reasoning – in these contexts, the spec model cannot be justified.

The mural competition winner is hardly better off than all those who did unpaid labour creating entries for it. The $500 prize money does not take into account the time taken to create the concept for the work, nor the six working days needed to complete the work on the large wall provided by Ponsonby Central. However, let us not forget that along with the prize money and art supplies, the competition also offered the winner an “opportunity to be showcased on the Ponsonby Central Brown Street art wall.” They listed previous “winners” like Patrick Reynolds, Gina Kiel and Jimmy James Kouratoras (some not winners at all, as they were commissioned – see Kim’s article for more on this) to implicitly endorse the prize and build the myth of future opportunities, which would surely come from having one’s work shown in such a prime location.

The mural competition winner is hardly better off than all those who did unpaid labour creating entries for it

Insignificant payment from institutions that otherwise seem able to provide adequate pay (for their staff, for contractors, for more established artists) is a prevailing issue in the art world. Prominent Wellington art collectors Jim Barr and Mary Barr say it is within the area of work being commissioned by institutions that there exists a more significant source of potential earnings for artists. “Institutions should certainly pay for work done by artists on their behalf, whether it’s filling their gallery spaces, giving talks, writing content, or holding workshops,” says Mary Barr.

Unfortunately, adequate payment for artists is always a controversial subject, and never more so than when they are being paid with tax dollars. The type of public scrutiny that was incited by et al’s selection as New Zealand’s representative for the 2005 Venice Biennale still exists today. Mainstream news media brewed a fuming public who were shocked at the $500,000 from Creative New Zealand and the Lottery Grants Board received by et al – a conceptual artist collective – to show at the international art exhibition. There were echoes of this contempt again with the recent unveiling of Michael Parekowhai’s The Lighthouse – a $1.5 million work, commissioned and funded by Barfoot & Thompson and an anonymous donor, and gifted to the city of Auckland. More recent still was the announcement of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki’s enormous budget cut, taking it from $12 million in 2012 to just $6.9 million. These cuts signal an unwillingness to value the arts at a national level. Meanwhile, sports stadiums and military operations are pumped with tax dollars.

...adequate payment for artists is always a controversial subject, and never more so than when they are being paid with tax dollars

Artists face a different flavour of exploitation when their work enters the secondary market, where it is usually resold to new buyers at a profit with no sale proceeds going to the artist. In the early 1970s when the Barrs began building their collection, they bought work from people they knew from art school. Mary tells me that they wanted to support their friends who were artists, as well as pursue their lifelong attraction to things they don’t understand. The Barrs have actively encouraged the adoption of resale royalties in the New Zealand art market, but received neutral and even hostile responses. “One collector even suggested that if a percentage of the profits were given to the artists, they should also pay up their share in any losses.” Despite others’ disinterest, the Barrs insist on paying living New Zealand artists 50% of the profit realised upon the sale of their work. “We are happy with the arrangement we have, and if anyone else wants to follow it they are more than welcome, but it is a personal decision.”

In 2007, a Ministry for Culture and Heritage discussion paper proposed the creation of an inalienable right of the artist to 5% royalties on all resales, which would fit within the Copyright Act 1994. Around 200 submissions were received with most in favour of the proposition, and yet it never went ahead. The first and only art business in Aotearoa to institute a resale royalty is Auckland’s Bowerbank Ninow, which opened in 2015. The auction-house-cum-dealer-gallery offers “a voluntary resale royalty of 2.5% of the hammer price to living artists whose works we sell either privately or at auction.” Artists Alliance, the not-for-profit organisation that works to support artists in New Zealand, still seeks to see the 5% resale royalty issue resuscitated.

Swiftly and effectively, they shut down the conversation

The ethical issues raised by artists reacting to Ponsonby Central’s mural competition are far more straightforward than the conversation and implementation of resale royalties. Unfortunately, Ponsonby Central never took the opportunity to engage with the art community about the ethical issues they raised. Instead, they deleted comments and blocked numerous people from accessing their account. In the same post in which their marketing team said “we welcome the conversation that is happening on our social media and we have endeavoured to keep as much of it as possible”, they declared they were closing comment sections on posts about the competition. Swiftly and effectively, they shut down the conversation.

Liew is well versed in the area of art and value – he is often involved in commissioning work, and artists regularly call on him to check quotes for their work and discuss licensing. Kim also helps friends to value their work, taking into consideration the length of time they have spent honing their skills and developing their concept before pricing it. I asked Kim and Liew why they think Ponsonby Central ignored this opportunity to engage with the community they ostensibly want to support. “It appears that Ponsonby Central couldn’t see anything wrong with what they were asking,” says Liew.

These competitions, calls for proposals and other practices in the art world draw from neoliberal values that encourage the individual artist to work alone and compete with other artists

This scenario is global. This year, the four shortlisted nominees the for the Preis der Nationalgalerie (a biennial competition open to artists under 40 who live and work in Berlin) Sol Calero, Iman Issa, Jumana Manna, and Agnieszka Polska, released a statement about their experiences with the competition. Their text provides criticisms familiar to those who have watched the mural saga unfold on Ponsonby Central’s Instagram. The nominees criticised the emphasis that was put on their gender and nationalities rather than their work in press around the competition, as well as the competitive framing of the award and its ceremony. Most relevant to this discussion, they criticised the lack of pay for artists’ labour – the prize does not have a monetary value and artists are not paid for exhibitions and public talks. They say:

There is an unspoken assumption that the participants are likely to be remunerated by the market as a result of being nominated for or winning the prize. As artists, we know this is not always the case. The logic of artists working for exposure feeds directly into the normali[s]ation of the unregulated pay structures ubiquitous in the art field, as well as into the expansion of the power of the commercial sector over all aspects of the field.

These competitions, calls for proposals and other practices in the art world draw from neoliberal values that encourage the individual artist to work alone and compete with other artists. This translates into a lack of shared knowledge about what proper payment and treatment of artists can or should look like. But social collaboration – as we see when our local artists comment together on Ponsonby Central’s social media and hold them accountable, or when the Preis der Nationalgalerie nominees unite to create a statement critiquing the prestigious prize – is fundamental for the artist’s survival.

The terms of Ponsonby Central’s competition and their confused reaction to the heartfelt criticism of the art community is not remarkable. From emerging to established, private to public, primary to secondary market, so many standard practices are formulated to take advantage of the artist. In spite of this, the indignation of the artists responding to Ponsonby Central shows that they aren’t disenfranchised – they’re fighting. When artists and their supporters come together and call out unethical practices, there is a value shift. The Preis der Nationalgalerie nominees ended their statement welcoming discussion on the issues they raise from the museum, its friends, sponsors and all relevant stakeholders “in the hope that together we can improve the situation for future iterations of the prize.” Artists are aware of their own worth and are willing to have these conversations. Their comments may be deleted or not responded to by those addressed, but I can feel the traction building – in Germany, New Zealand and around the world.