Reality?: "Election Billboards", Gone Girl and Playing Broken Systems

Samuel Te Kani on what one billboard can tell us.

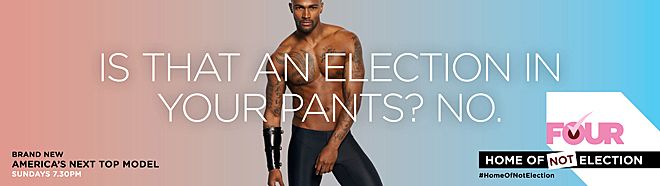

During election week, back in September, I came across a rather disconcerting billboard. I find billboards invasive at the best of times, but this one was particularly insulting – an ad for Four’s reality TV programming, it featured an image of Tyra Banks striking a would-be model pose (let's charitably say she's graduated to self-parody). Across her visage, boldly printed: 'so much fierce, so little election'. Four: the #homeofnotelection.

I don't know Ms Banks personally, but I'm not entirely sure she'd be comfortable being poster girl for New Zealand’s loud, proud commercial median of ignorance, a wilfully apathetic streak that MediaWorks New Zealand’s Four inexplicably deemed appropriate to highlight (and subsequently legitimate) during an election.

The billboard did and said a lot, but sorest in my mind were the following functions. Firstly, it assumed (or dictated) that the station's viewers are mostly indifferent to the election – that it’s valuable to them as a peripheral entertainment only, and even then as an inferior spectacle to America’s Next Top Model (Tyra's undying legacy, after her late modelling career and talk-show). Secondly, it licences this indifference. Which led me to my next gut reaction: how was this campaign allowed?

Is our insecurity as a smaller country so normalised that the general public is encouraged and lauded for dissociating from its own election, even as other mediums (including Four's own ad breaks) desparately urged them to enrol, let alone vote? Are we so besotted with the global reach of larger countries that we'd prefer an hour of American-made programming to coverage of our own nation's future-in-progress when it truly counts?

At a time when attention should have been more focused then ever on our own backyard, why is our popular media so intractably and preferentially American? In light of the recent election, who would seek to gain politically from a New Zealand identity being confused with an American one? If someone does, should we allow U.S. branding to take root more than it already has? Are there economic benefits which might explain this saturation? Or is it high time to detach from values and sensibilities that don't describe us at all?

After stewing, I realised my misgivings ran deeper to the product itself – not just ANTM, but its peers. Identifying some of the functions of reality programming reveals a synchronised effort of Americanisation, to which the billboard is merely instrumental.

Because reality television can be an especially insidious genre. Constructed environments with set premises (by writing teams in the pocket of broadcasting agencies with agendas of their own), are posited, on the face of it, as pure documentation. Here, I know that some discerning readers might scoff (with reason), and defend their right to enjoy the grotesquerie of shows like Jersey Shore and its British spinoff, Geordie Shore, if only to valorise their own tribes by comparison.

That same readership might contend that anyone approaching such material without the requisite criticality is missing the kernel of 'ironic' enjoyment the reality-framing begs. These programmes are nothing to be taken seriously; rather, their antics serve as a cautionary example (or spectacle). And if you swallow these spectacles any more than you should, if you aspire to the featured cultures with consumer gusto, you're probably deserving in your ignorance.

But as you lose yourself in your own knowing chuckles, remember that the camera’s representation is selective. Even to a savvy viewer, it legitimates certain forms over others, stamping certain ways of being as acceptable and expressly forbidding others by default. This is the 'godliness' of the reality-framing, where television becomes ontology (a branch of metaphysics on the nature of being). All media representation does this, period - but only the reality-genre makes production biases so opaque, deliberately obscuring selectivity for the effect of journalistic transparency (did I just call Keeping up with the Kardashians journalistic? Sure, in that the show presents itself as the gathering, processing and dissemination of news and information about a group of real people’s lives).

The Jersey/Geordie Shore phenomenon is essentially inflated character study. The camera’s eye frames these monsters with sly incredulity, but not censure; products of a culture that's somehow aggrandised even while the show's vainglorious subjects make hapless satire. And that's debatably the show's purpose; to grant licence to consumer culture in the moderate form it assumes in most of its viewers. So long as we ourselves aren't pumping and primping until we're muscle-bloated and tangerine, running dye through our hair until it’s thinner than cotton, or binge drinking our way to emotional ruin (cough), then we can be serenely contemptuous. We can laugh while still recognising the motivations as acceptable consumer-drives (that is, practices recognisable to our own consumer habits, albeit to a lesser degree).

Another species entirely are the likes of Keeping up with the Kardashians, The Real Housewives sagas, The Hills, Laguna Beach and so on. Unlike the former, which parody a culture we can still identify, these shows basically embody the American Dream in its ultimate stages. It's a dream that's mostly impossible, and from which we're excluded (its exclusivity is integral to its appeal).

The values are wealth and fame, replacing Shore's workaday consolations and notoriety (alcohol, body image, sex) with the signifiers of extreme wealth. Fame as a value is intrinsic to the reality-show format, elevated above and disembodied from specific achievement and becoming a naturalised state. In other words, from here on out, Kim Kardashian can make a career out of simply being Kim Kardashian (bless her).

There's an underlying fantasy which your average viewer feels alienated from yet helplessly drawn to in both castes of 'reality' programming - one where the media eye is drawn to excess, as much for the spectacle as for reasons instrumental to the consumerist environments we move through. Everyone wants to be validated, and the 'reality' lens denotes the practices and behaviours pleasing to its omniscience. Generally, they’re the ones outside the range of your average viewer’s daily life – because of mobility, because of confidence, because of commitments, because of money. The injunction is to 'be more', playing to the chronically dissatisfied and undermining the possibility of gratification outside its own garish brushstrokes. Small is not beautiful.

Furthermore, this genre actively normalises inequality by citing different socioeconomic positions as 'novel' , shaving the spectrum of its hierarchical elements. Instead, the practical distance between poverty and wealth is presented horizontally, a selection of consumer-ready 'lifestyle' choices that can denote nebulous aesthetic ideas of ‘taste’ and ‘class’, awaiting your perusal. Like a catalogue.

This effectively strips injustice of any urgency. At the other end of the scale, UK Channel 4's Benefits Street is a specific example of the reality-eye embracing (and desensitising) the lower as much as the higher rungs. If the Kardashians about aspiration, and the Shores are about applauding your moderation, Benefits Street is a picture of a worse alternative than either. This reality show follows the lives of unfortunates living in Britain's most benefit-dependent district (Winson Green, Birmingham) servicing voyeuristic appetites for the misery of others, for a different and perverse kind of envy, and for scapegoats.

It's clear these shows call viewers to keep a close eye on the other (what they have, what you’ve got, and what they’re getting that you’re jealous of) making 'lifestyle' a competitive sport with possible models abounding. But circumstance is always the one factor neglected in the representation of these lifestyles, and one wonders what the contingency is to living like this? Is there a trajectory for discerning aspirants from society's lowest to its highest, to live the kind of life most reality television affords? Is such an ascension possible? Perhaps - though you'll need a bigger screen.

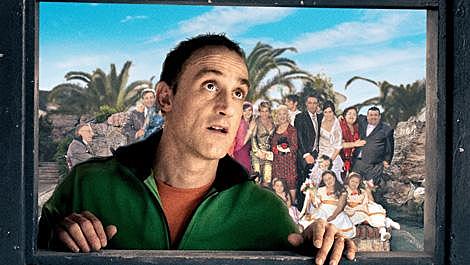

There's a recent Italian film that demonstrates the obsessional/metaphysical lure of 'reality' programming, aptly titled Reality (D: Matteo Garrone, 2012 - best known for his 2008 Camorra epic Gomorrah). The protagonist is a working-class family man fixated onto getting into Grande Fratello, the Italian version of Big Brother. After his unsuccessful audition, he believes he's being secretly scouted by agents for the competition, when he's actually having a psychotic break, projecting his ambition on perfect strangers and superimposing the media-eye on his everyday life.

The very last scene shows him going to a public mass in Rome, only to sneak away from his family (believing him to have recovered from his strange obsession), and break into the Big Brother house. It ends on an aerial view of the house with our protagonist leaning back, staring ecstatically into the camera, embedded within his fantasy and validated finally inside Big Brother's'field of vision. It's obviously meant to parallel a religious experience, but it’s also a look of madness, echoing the closing image of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho and not dissimilar in intent. In Psycho, the camera holds the expressionless gaze of Norman Bates and audiences are forced into identification with him, a relationship that screens the viewer's own potential for breakdown. The killer is framed as an Everyman (a natural mid-point between pathology and conspicuous consumerism, which is revisited in the movie adaptation of American Psycho more blatantly).

On the other side of the Atlantic, David Fincher’s new film adaptation of Gone Girl exemplifies a related psychotic dissonance. It's a missing-person mystery both mediated and ultimately resolved by its nationwide, TV-mediated lens.

The film’s eponymous protagonist, Amy Dunne, vanishes, fakes her own murder, and leaves her husband as the prime suspect. We observe how she’s coolly manipulated the media circus attracted to the Dunnes’ 'story'. Reported with all the media’s breathless narrative vapidity, the whole saga becomes framed as round-the-clock reality TV in its own right. Finally, agreeing to a live chat with a celebrity talk-show host to clear his name, Nick Dunne speaks directly to his wife. Amy reads this as a legitimate endearment, missing from their marriage before and possible only through the lens of the media she assembled (through anonymous tip-offs) to crucify him.

His love is confirmed for her only through this televised confession - on her return (fabricating an abduction by a deranged ex, another reality twist too good to be true) the pair remain together, posturing for a thirsty media and enacting a picturesque bookend to their 'troubled' marriage.

Amy has committed fully to the logic of the media eye. She has total faith in its legitimacy and consistency, the irony being she's upheld its values by merrily subverting them (extortion, murder). Or perhaps she's penetrated to the truth of these values and acted out an imperceptible core of dissociative pathology with a Nietzschean kind of brashness. The major difference between Reality's protagonst and Dunne is that the latter manages to force the 'magic circle' of the media eye over the existing features of her daily life, weaving a bloody narrative it can't help but witness, where the former clumsily forces their way into the Big Brother house with a desparate, bloody-minded literalism (clearly, ascension is not possible).

Fincher leaves audiences with a mystery, closing with that very same 'gaze into the eyes of madness' and forcing audiences to question their own dissociative relationship with the institution.

We’re not seeing reality talent scouts everywhere we go, or making elaborate plots via media to escape our lives, but both Fincher and Garrone’s films say something about a public fatigued by and inured to media, sometimes to the point of psychosis. With the traditional sources (TV news, election debates, panels) it could be a problem of incoherent or irrelevant modes of delivery, or maybe a justified distrust of typical mainstream vehicles. Either way, the facilitated alternative would appear to be escapism, of an ilk specifically calibrated to usurp New Zealand values (whatever those are) with a standardised foreign set.

I realise this is cultural imperialism, and that it’s nothing new. But if I'm going to be told that Tyra Banks tragically lording her has-been career over a bunch of up-and-comings is more deserving of my attention than political upheaval in my own country (by a fully endorsed broadcaster ad-campaign, no less), then I'd argue it rings truer than ever.

It's a situation I'd liken to Reality's protagonist - working-class man rejects the humbler pleasures of his own life (including his own family), turning in hope to a fantasy purposefully rendered to exploit (by pretending to overcome) the gripes and resentments of a residual class-system (sorry, I meant 'socioeconomic grouping', there are no class-systems in the western world. Ahem).*

Although it’s ultimately a comedy, Reality is also a cautionary parable about the dissonance exposure to such media engenders, and a prescription the hero ignores - an embrace of local values (the protagonist's extended family, the market community they're a part of) to remedy the glamours of commercial-hyperrealities. Lest we forget our own election.

It's disheartening to observe such sentiments being abandoned in this country for a stake in (a pale version of) the 'American Dream' that these shows endorse, rallying converts through affluent lures. While it’s not surprising that our NZ channels and media companies would attempt to mimick a commercially successful model, it’s surprising how quickly our stabs at the 'reality' genre are content to (badly) map onto their American counterparts, to wear the same ideological accessories but forget to bring a map to pinpoint their very different context.

The Ridges, for example, is a ludicrous attempt at American celebrity staged on a Kiwi scale. If we’re to give it a redemptive reading, it works as a commentary on celebrity culture while dually trying to inhabit it, but the show unwittingly proves a cultural incompatibility with broader and broader strokes as time goes on. The particular appropriation here is the nubile socialite, moving through privileged circles on the crest of a name/title. That this isn’t really the New Zealand way of doing things might be lost on a national audience who perceive Auckland as lording some global glamour over the rest of the country. But Ponsonby is not L.A.

Then there's The GC, which matches our notorious drinking habits to the 'work a little, play hard' mandate glorified by Jersey Shore (as I first began to write this, an All Black too drunk to catch a plane licked his wounds) and reduces the story of the diaspora of young Māori flocking overseas to a sort of Wild On E: Surfers’ Paradise Edition.

There's also The Block, valorising the kinds of domestic fantasy New Zealand has been guilty of too (No.8 wire mentality, quarter acre dream home) while assimilating competitive American values to mixed effect. Though not every contestant couple is a married one, there's a strong heteronormativity throughout, glorifying the trappings of married life at a specific socioeconomic coordinate (which with housing prices being what they are, is decidedly upper-middle and thereby unattainable to an impoverished majority).

It would be one thing if our leaders held themselves above this fray. Once, we were exhorted to “be more”, in an appeal to our character rather than our consumption habits. Instead, they participate in it with an irksome kind of jokiness. It’s Key on Letterman, making jokes about this country's inferior status that wouldn’t have survived a first-draft Flight of the Conchords script to the delight of American audiences. Our Prime Minister, reducing himself to the spectacle of celebrity, servicing another home audience’s egos. He makes it all seem like rote entertainment. Taking cues from our own political leader, why should I heed an election when Tyra's got a new season of Model?

Reaching a certain level of calculated disenchantment, and kept in perfect ignorance, a public eventually dissociates from its political leaders, embracing the available distractions to sublimate their impotent rage (another drink, anyone?). At which point only the veneer of democracy is importantly maintained while the political strata have relative freedom, restructuring our lives overnight should they choose with games of doublespeak and subterfuge. Our permission is no longer required.

Resistance isn't impossible. An awareness of how the current status quo has been structured is the first step towards engaging those apparatuses and renegotiating the purposes of our media. Going back to Gone Girl, Amy Dunne could be seen as a fierce example of powers which disparate medias have failed to deflate. She exploits the system by undermining or taking advantage of every moral code, every narrative, and every priority it depends on. This is the irony, that her superhuman impetus stems from dissonance itself, the culture she sees around her followed through to perverse ends. She grasps the radical contingencies and gross dichotomies comprising her reality, and also sees an illusion to be upheld at any cost. A fantasy to kill for.

In what some might see as an abhorrent revenge fantasy, Gone Girl depicts the re-empowerment of subjects systemically entangled, apparently without hope. Re-empowerment doesn’t have to play out like Fincher's high thriller - it doesn't have to be strictly about the self, and it doesn’t have to come at a human cost. But it can exploit the system it’s presented with. Our only chance of a radical break is, ironically, to play the game with manic gusto, thereby adjusting the parameters of what's possible.