Rekerekeu ma Abau: Connecting to My Land

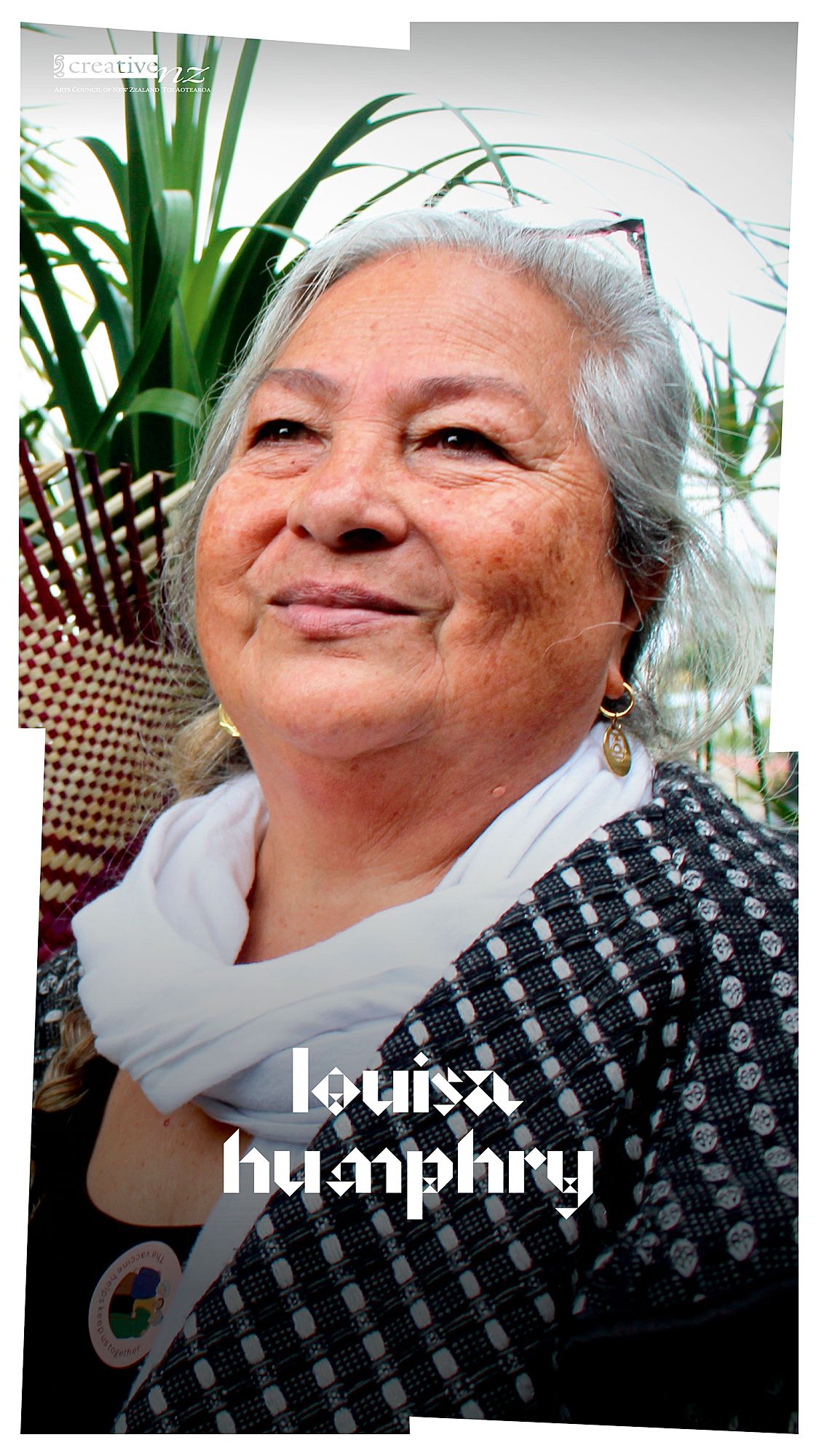

From arriving in New Zealand with no money, to being honoured for her service to Kiribati culture and community in Aotearoa, for Louisa Humphry being armed with te rabakau ensures I-Kiribati knowledge and practice can be carried into generations to come.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Lagi-Maama had the honour of sharing time–space with Louisa Humphry. After a beautiful feed, we sat on the deck of her dear family friends Kaetaeta and John Watson’s auti/fale and began our maroro/talanoa/conversations. We laughed, we cried, we reminisced, as Louisa took us on the journey of her life.

My life journey

My name is, very simply, Louisa; my maiden name was Murdoch. My grandfather, George McGee Murdoch, had come from Scotland when he was a 15-year-old man and settled in Kiribati, on the island of Kuria. Most of my siblings were born on the mainland of Tarawa but I was born on Kuria, which was very special. And people laugh when I say this, but I was actually born under a coconut tree. You see my mother, Lotebina Murdoch, is from another island, Abaiang, and had come to Kuria to settle with my dad David Murdoch’s family. My mother was very shy and when she was pregnant with me, and went into labour, she decided to go into the bush to have me, because she didn’t want to bother anybody.

I grew up very conscious of the fact that I wasn’t ‘fully Kiribati’ and that I had some other blood in me, which at the time I hated, it made me not quite fit in. But I am so sure that that feeling is what made me who I am. I became very connected to my culture because I so wanted to be a ‘Kiribati person’, and not only that but also to appreciate the cultures that are in my makeup. At the same time, I needed to be proud of my grandfather, who left Scotland when he was a young man – I wouldn’t be here without him coming and settling in Kiribati.

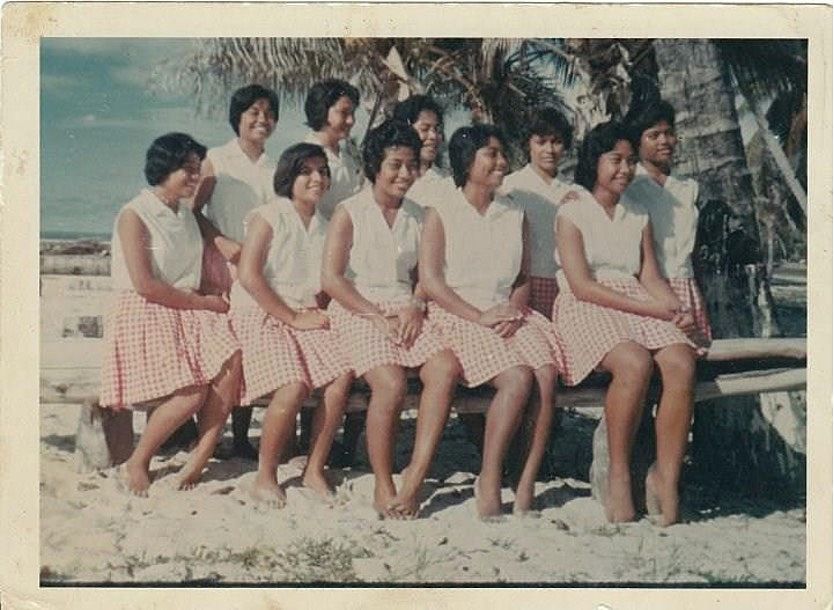

School photo, 1969. Top row, left to right: Louisa Butcher, me, Aonga Kofe, Julia Edwards, Keina. Bottom row, left to right: Rosa Muller, Lucy Muller, Nterei Tewatu, Tarawa, Taoati Tooki.

I grew up on Kuria and when I was old enough to start school my parents moved us to Bairiki, on the main Island of Tarawa, which is where our government is, and that is where I went to primary school. After primary school, I attended a Catholic high school, Immaculate Heart College, run by nuns, which was very strict – you hear about how tough life was in convent schools and it’s so very true! There were so many restrictions. I wasn’t very popular with the nuns because I was very outspoken, but they were wonderful, really! I think going to a school like that makes you a strong person.

But, yes, I was eventually picked as one of the ten girls from Immaculate Heart to continue my education into my fourth and fifth form, at the government-run King George V and Elaine Bernacchi School. And, lo and behold, I was picked to be Head Girl. One of the nuns came especially across the waters from North Tawara to tell my headmaster that he must be a stupid man – “Do you know what this girl is like, she will talk back to you, and she’s very outspoken.” Our headmaster at the time, a very lovely man from England named Mr Putnam, said to the Sister, “That’s the very stuff head girls are made of!”

I wasn’t very popular with the nuns because I was very outspoken, but they were wonderful, really!

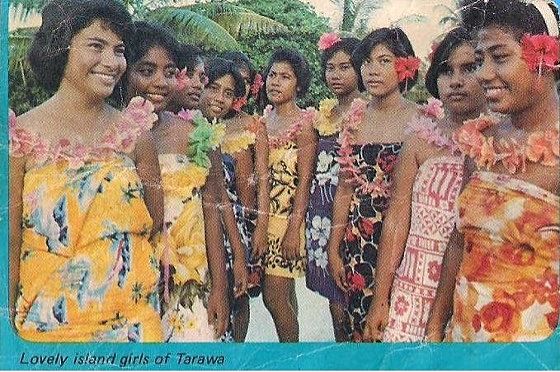

Me and my classmates from King George V and Elaine Bernacchi School in 1969. Left to right: Me, Tarawa, Louisa Butcher, Rosa Muller, Tetangi, Aonga Kofe, Taoati Tooki, Taberauea Teiwaki, Lucy Muller, Nterei Tewatu. Photo: Pacific Island Monthly

From there I was lucky enough to get a scholarship, which brought me to New Zealand at the tender age of 17. I went to New Plymouth Girls’ High School, which was such a culture shock! The food, the climate, the people. I thank God for the people, because they were so nice and made me feel at home in such a foreign land.

I spent my high-school years in New Plymouth and then did my studies for nursing at Whangārei Base Hospital. In my third and final year of nursing, my dad became really sick. We weren’t allowed to go home every year the way scholarship students do now, but I really missed my dad and I didn’t want him to pass away without seeing him. I hadn’t seen Dad in three years, so I decided I would go home. It was right on the week of our state final nursing exams, so I missed out on my final exams. I didn’t go back, because according to the scholarship board I had broken the rules and shouldn’t have left. Because I was a rebel, I said, “Okay, well I’m not going to do any more schooling,” and decided to stay in Kiribati, which was lucky because that’s when I met a lovely VSO (Volunteer Service Overseas) volunteer from England, named Jack Humphry.

Jack wasn’t keen to stay in Kiribati because he didn’t want to take jobs away from local people. So we decided that New Zealand would be the best place for us. We scrimped and saved to get our fare – as a volunteer, Jack only got pocket money and I didn’t really have a career as such. I told my dad there was no way he was going to help me because he had nine other children to look after. So we saved up our fare, then came to New Zealand and settled here. And as much as you make a life in a different country, I think your home island will always be ‘you’.

As much as you make a life in a different country, I think your home island will always be ‘you’.

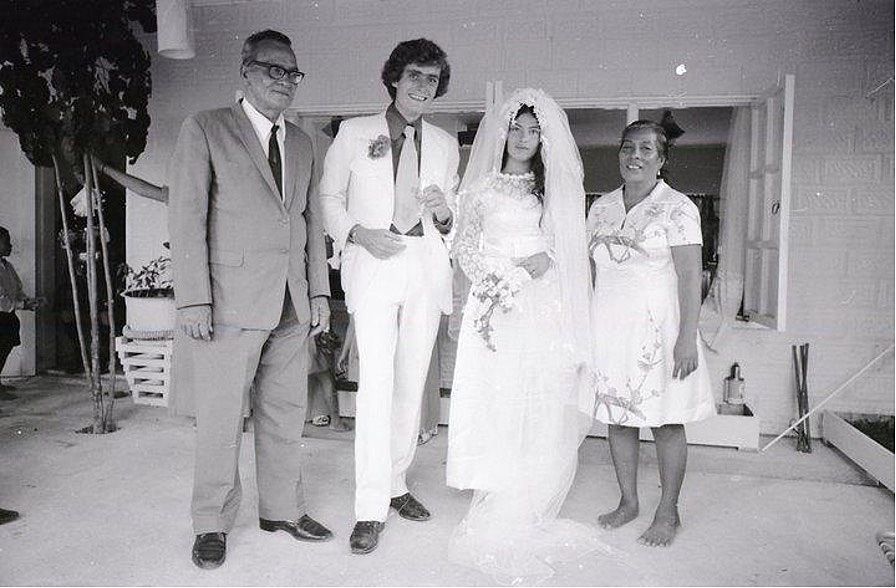

Jack’s and my wedding in 1973, with my mum and dad, Frederick David Murdoch and Iotebina Teririko Murdoch.

Once we arrived in New Zealand, I was busy growing a family and working part time.

Actually, Kolokesa, I cried when I saw your girls at the Dawn Raids Apology, because when we came to settle here in the 70s, we faced that racism. Jack would go flat hunting and be told ‘yes’, but when I turned up with him to see the flat it was ‘no longer available’, so we went through those hard times, too, that many of us Pacific Island people experienced. But we managed, and eventually found a flat, and Jack got a job.

The funny thing was, Jack actually got his job on our way from Kiribati to New Zealand. To save money we travelled by boat to Fiji, and from Kiribati it took ten days – which I remember vividly because I became very seasick. When we got to Fiji, we stayed with my cousin Lily and her lovely husband, Henry Sokimi, for a week. We then took the bus to Nadi, and on the bus an older gentleman who sat opposite us asked where we ‘young people’ were going and Jack said we were going to try our luck in New Zealand. They started talking and Jack shared that he was a fitter–welder–engineer and would look for a job as soon as we arrived. This lovely gentleman was the owner of Transport Containers in Glen Innes, Auckland, and gave Jack a note to give to the manager, followed by these magic words: “You’ve got a job!”

I cried when I saw your girls at the Dawn Raids Apology, because when we came to settle here in the 70s, we faced that racism.

When we arrived in Auckland we had no money, so we took all our treasures – our watches, Jack’s gramophone and a camera (he wouldn’t let me take my ring off) – to a pawn shop, and thankfully they gave us some money, which we used for our flat deposit and to buy a mattress. We used the rest to buy coffee and bread, which we survived on for three weeks until Jack got his first pay.

I tell our story to my children and grandchildren all the time, because if you start like that in life you really learn to appreciate every little bit of luxury that you have. My dad always used to say, if you are handed things on a plate, you never really appreciate how you need to build your own strength.

We carried on with life, working and raising our children. Focusing on my family, I forgot about myself, and didn’t realise how much I needed to connect back home. It took us ten years before we could go back, and when we finally did I think that was really when I found my passion for wanting to carry on and never, ever forgetting who I am and where I come from, my roots, my island.

Absence makes the heart grow fonder – it’s definitely true for us as diaspora, in fact I think I’m more Kiribati now than ever before

I remember flying home and looking down at these tiny, tiny stretches of land, and feeling so happy – being home reminded me of how much I really loved my childhood on the island, and how much I loved everything about being part of village life on the island. I think, for all of us, its where our roots are, we aim and need to stay connected – what’s that saying? Absence makes the heart grow fonder – it’s definitely true for us as diaspora, in fact I think I’m more Kiribati now than ever before, if that is possible!

These memories I’ve just shared, of me as a young child growing up in village life in Kiribati, have helped me to land on what I want to focus on here. While I can’t capture everything, I want to concentrate on the bwaka ni buto celebration, an event stuck in my mind that provides an insight into a Kiribati cultural practice that reconnects back to my roots and my land.

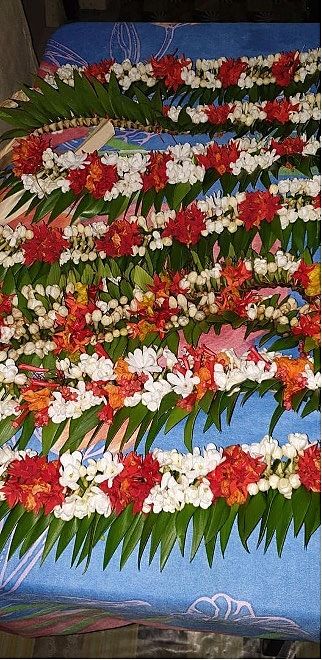

Samples of te itera, made for a dance event on my island, Abaiang.

In Kiribati culture, when a baby has parted with its umbilical cord, it’s a time to celebrate. This celebration is called the ‘bwaka ni buto’.

Bwaka ni buto celebrations

In Kiribati culture, when a baby has parted with its umbilical cord, it’s a time to celebrate. This celebration is called the ‘bwaka ni buto’.

Women weave te inaai, a quick ground cover (mat) for the arriving family.

Girls and boys of the family decorate around the yard with traditional te bwerei, and food baskets are woven to use as plates.

Garlands are made, including te itera, a very specially constructed garland for the mum and dad, and a little bracelet is woven that will have the fallen umbilicus wrapped and put inside for the ceremony.

Making te itera, Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, June 2019

While this preparation is going on, the older men carry on their daily chores, some carrying on with te waa (canoe) building, some building a Bareaka (hut to house the canoe). The older ladies are gathering their pandanus leaves for the more serious and intricate weaving of fine mats. There is also te rau (thatch) for repairing roofs of huts.

Of course, the young girls are going to be dancing, so there are the urgent repairs to existing costumes that have been passed down through generations, but also new ones to make – after all, these girls grow up fast! Te riri te karoro (black skirts) need to be revived (te kabweari), it's a process we have for reviving them, like smoking them. Te ramwane (chest straps), karuru (arm decorations) and now te tai for their head adornments made from te kakoko (young coconut leaves).

Not forgetting, of course, the boys that will surely be part of the dancing. There are their dancing mats to make sure they still fit, and all their accessories. A lot of these are costumes passed on but there will surely be new ones to make.

A te ngabingabi (fine woven mat) for baby to be placed on, is needed now that ea bwaka butona (baby) has been separated from its umbilical cord.

In the meantime, village tasks are still happening. The men constructing the canoes need more fine string to tie the planks together. A group of women are in the sea while it’s low tide and are digging out te benu (husk that has been buried months ago). They are ready to be cleaned and dried so that te kora (coconut fibre string) can be made. They will make quite a lot because the canoe builders need the finer ones, but there is the construction of a new house and they will surely need yards and yards for that, too!

Back to the bwaka ni buto celebrations. A te ngabingabi (fine woven mat) for baby to be placed on, is needed now that ea bwaka butona (baby) has been separated from its umbilical cord. Perhaps a woven te abein (basket) will also be made for baby’s clothing to be stored in.

Te uu (eel trap), Collection of Auckland Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira, 1939.98, 24479.1

Food for the feasting is now the immediate focus. The men have te rabono (eels) to catch, which are quite a delicacy. Te uu (eel trap) is prepared. Te riena (scoop net made from te kora) is pulled out. The canoe is made ready.

Harvesting te babai (kind of taro) – the very best crop from the family babai (pit)!

Of course, replacement crops will need to be planted – ribanaia (cultivate the new one) – feed it – so immediately you check the root and then replace it.

The above memories creep into mind when I think of the beauty and magical intrigue of all that revolves around our Kiribati heritage art. These are all te rabakau (knowledge) that enables daily living and all that our life is surrounded by, that influences all these beautiful creations that are made to celebrate the new life, with our bwaka ni buto celebrations. I am intrigued and will be forever amazed by all of the components involved, where everyone in the village has a creative role to play.

And today, I love to create – whether it’s a mat or the different components of a male, or female dance costume – and also to introduce more contemporary twists to all that I have observed so it does not become lost.

Memories creep into mind when I think of the beauty and magical intrigue of all that revolves around our Kiribati heritage art.

Te rabakau, knowledge

Te otanga stands out in my mind as te rabakau (knowledge) that is almost lost. The purpose of te otanga as war armour is the very reason it is not made anymore. I personally am passionate about recreating te otanga, but more than that is the love to seek the makers in Kiribati. Tai karaba te rabakau ba a kawa natimi, tibumi ao riiki aika imaira. Do not hide your knowledge, think of your children, grandchildren and generations to come.

Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, me, Lizzy Leckie and Kaetaeta Watson at the Pacific Heritage Arts Fono in Wellington, 2019, with te otanga.

Our Kiribati people are now scattered all around the world, and with climate change threatening our beloved homeland we run the risk of becoming a ‘lost nation’ – that is my greatest fear – but if Kiribati disappears then we can strongly stand as Kiribati people who know where they came from and live proudly with the fact that they are I-Kiribati – which is why we need to be very open about sharing our history so it doesn’t become lost when we are gone.

Otintaai, 2020. Photo: Jo Moore, Te Papa.

Otintaai tells a story of hope and agency in the context of climate change, speaking to experiences of I-Kiribati communities in both Kiribati and Aotearoa New Zealand. Otintaai in Kiribati means sunrise. It is the name that Kaetaeta and I came up with for our female Kiribati Climate Change Warrior.

Left to right: Te Papa Tumu Whakarae Chief Executive Courtney Johnston, Jack Humphry, me, Isabella Moarerei Levet, Kaetaeta Watson, John Watson and Tekariti Susan Skeggs with Otintaai at the handover ceremony, 1 May 2021. Photo: Jo Moore, Te Papa

While Otintaai was originally made for the exhibition Ā Mua: New Lineages of Making at The Dowse Art Museum, exhibited from June to October 2020, she has now been formally and lovingly handed over to her new custodians, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, which we are so proud of (and something we would have never imagined in our lifetime).

Otintaai is a beacon of hope and Kiribati pride that we hope generations of Kiribati Kiwi descendants will be able to see and enjoy in the future.

Honouring

We honour the land we're on now because of our connection with our own land.

This is so important, because this is not our land but we made it our land, so we need to connect with it strongly and honour the people that come from here. So our teachings and our knowledge that we've got through tangata whenua are very important and we will never, ever forget that. When people come to the market where we sell our works, and they say things like “Oh that's Māori art”, we're quite strong in saying we've learned from Māori elders but this is our art, which is Kiribati art that we've carried, but we've used harakeke from here. I think it’s really important, too, that we show ourselves and that we shouldn't stop just because we don’t have ‘our’ materials here.

Te tai made by Kaetaeta Watson and me at Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery. Photo Te Uru.

Samples of my work with harakeke.

Samples of my work with harakeke.

Let us carry on, if not traditionally then contemporarily. Make te tai (headgear) with straws. Make te itera (Kiribati traditional garlands) with plastic flowers. I guess the other twist is that these are materials that rubbish our earth, so let's put them to good use instead of throwing them away. You can make beauty out of everything, even if it’s plastic. Te tumara (shell hip adornment) and te katau (coconut-shell hip adornment) can be replaced by beads.

Kaetaeta Watson and me speaking at the Pacific Heritage Arts Fono, in Wellington, 2019. Photo: Raymond Sagapolutele

Transmission of te rabakau

I am very passionate about sharing this knowledge and ensuring that my children and grandchildren have seen, experienced and understood what we have done in the past and in the present for them. I want to ensure they always feel connected and proud of their heritage and culture, that I can proudly say that they have connected with their Kiribati side as well, because Jack’s English side is around us all the time.

Our children doing their traditional Kiribati dance for our independence anniversary celebrations in the mid-1980s.

We came with nothing, but we built ourselves up, and I mean we were not rich, but we've lived the life that we want to live and we're happy. We've worked really hard all our life and I’m just acknowledging that you can build your life just by accepting the culture that you come from and being strong in acknowledging the journey to get there.

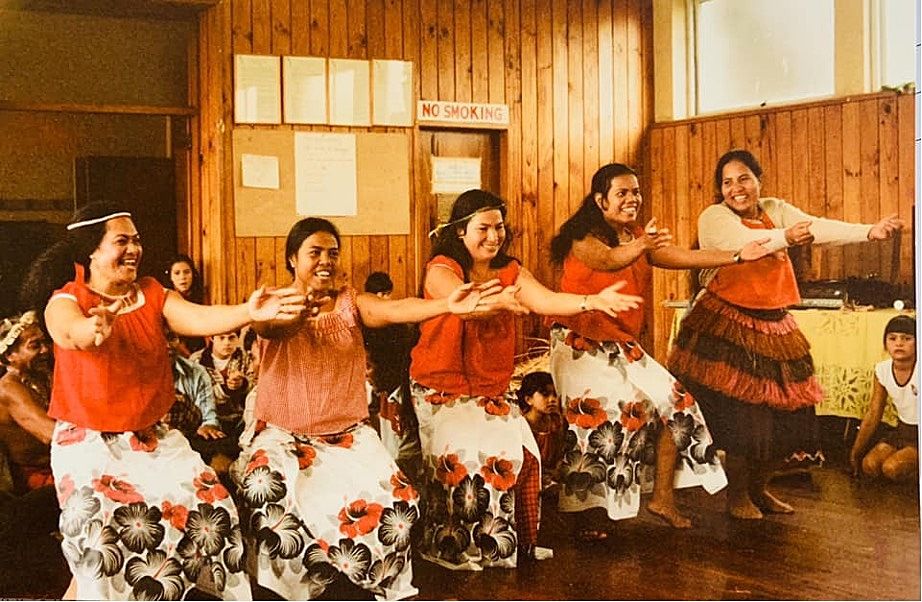

My friends and me dancing for one of our independence anniversary celebrations in the early 1980s. Left to right: Tongafiti Cross, Babera Tetimra, me, Kaetaeta Teetu, Betuao Chung.

think our generation, especially, has got to be so proactive in connecting our children to their roots because they've got no other means. If we are in a strange land that really speaks a completely different language with different practices, different cultures, then who will teach them? If we don't do this, then how will our kids know where they are from and who they belong to?

When we lived in Hamilton I used to go into our children’s schools and teach our Kiribati culture and practices. I would see their pride, which was everything.

By not sharing ‘their’ stories we are depriving our children by not letting them build their own stories – their own chapters – from ours.

Me (seated) dancing te bino, 1980s.

During Kiribati Language Week my family Zoom each other each night – sharing what we did with and within our communities to celebrate being Kiribati. It is so important to keep sharing our stories, as we are keeping our culture alive for our next generation.

If we don't talk, if we don't tell stories, if we don't show how we lived and how we do things, then how will my grandchildren and great-grandchildren convey it to their children? Where does the story start for them? By not sharing ‘their’ stories we are depriving our children by not letting them build their own stories – their own chapters – from ours.

Legacies

I think of ‘legacy’ and I can proudly say that we have tried to ensure our children know their Kiribati roots, because if we have done that then our grandchildren will know theirs – so that our grandchildren, when asked where they come from, don’t say “Hamilton” but can proudly say “Kiribati”. Teaching my children to speak Kiribati was really important. But we are doing it the traditional way because we haven't written a book about it – it'll be nice to actually write a book about things like that – but we conveyed it by storytelling, which is our very way of conveying our history and our stories.

Left to right: Our children Debbi Levet, Sandra Humphry, Erena Humphry and David Humphry.

Me and Jack with some of our family, Christmas 2019.

My older granddaughter, Tarike Letitia, rang the other day and wanted to know more about her namesake, my maternal grandmother. We have a Kiribati saying that if you are named after someone you pick up their traits, so I was sharing my memories of her as an old lady who was so kind and nurturing. I remembered how she only wore a grass skirt, except when she would go to church. She never went to school and probably couldn’t read or write, but she was an amazing storyteller and would tell us grandchildren the most amazing stories.

We have a Kiribati saying that if you are named after someone you pick up their traits, so I was sharing my memories of her as an old lady who was so kind and nurturing.

Key, for us, was ensuring we kept our traditions and ceremonies alive, especially for our daughters, who have important ceremonies in their lives that we honour as I-Kiribati. One of these ceremonies is a girl’s first menstruation. It’s usually led by a grandmother, but obviously because we are here in New Zealand we had to reach out to one of our Kiribati Mamas here, who came and led this for us. Now we are doing the same for our granddaughters, and what was key was teaching our daughters so they can continue these traditions.

Te itera made by me for my granddaughter, Tia Mihaere, for her coming-of-age celebration (first menstrual period). Photo: Debbi Levet

We are going to be starting our own cultural group, with the first meeting taking place in Papamoa at the end of this year. It will have my family and Kaetaeta’s and a few other families. We are very excited about this, as it will ensure the transition of our knowledge continues. Even our boys, growing up, before their rugby games would say, “Where is Mama’s magic oil?” This began when their fathers were young and my mother sent coconut oil that was scented with all these different flowers from Kiribati – they would rub the magic oil over their chest and legs, which would bring them luck.

We are very excited about this, as it will ensure the transition of our knowledge continues. Even our boys, growing up, before their rugby games would say, “Where is Mama’s magic oil?”

I must acknowledge my husband, Jack, who has been such a strength. Kaetaeta and I were talking about this the other day – that if we had married any other kind of men, would we be as strong in our culture or practice as we are now? We reminisce of the early Pasifika days and Jack and John running the food stalls – two Englishmen speaking Kiribati and explaining how the food is made and dried – they were so wonderful! We used to joke around, saying that they were more Kiribati than we were. I remember at the start of the Pasifika Festival, Kaetaeta and I (and our families and children) would leave at 3am from Hamilton to get to Western Springs in time to set up our little Kiribati stall. Our daughters performed (one is now a grandmother herself) and we had so much fun. Kaetaeta and I ran weaving classes and activities, and John and Jack ran the food stalls.

Kaetaeta and John have become so close to us – they're closer to me than my own sisters sometimes, because my sisters are not here. They became our family, our children grew up together and even performed together at Pasifika when they were very young, and we have attended each other’s events and family celebrations from the beginning – we are so grateful and blessed to have had them in our lives and on this journey.

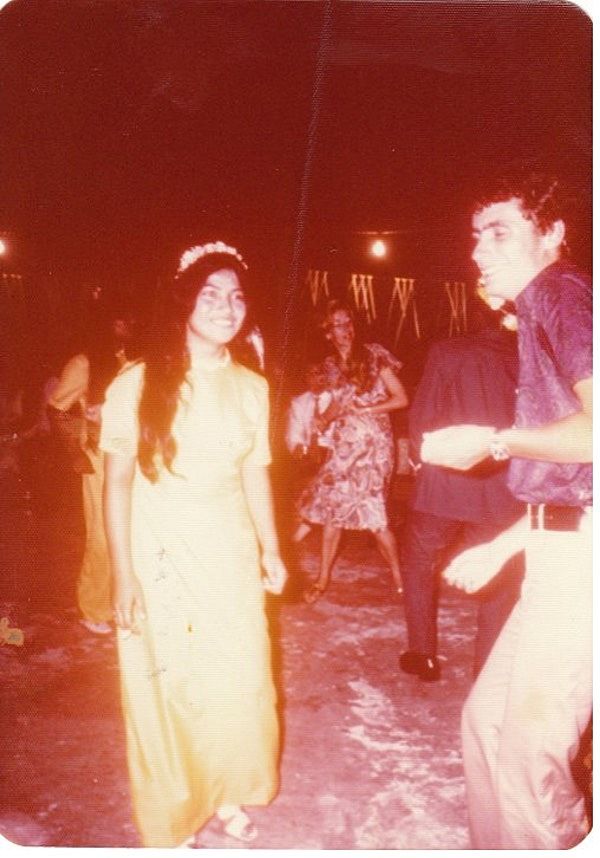

Jack and me dancing in Kiribati, 1972.

The ‘magic’ of creating

Those of us that came in the 70s worked really hard to be recognised, especially as the ‘smaller’ islands. I remember there was a Pacific Women’s Leadership group who I approached about joining, but when I told them I was from Kiribati they said sorry, it’s not one of the islands they cover. That was just one of the many struggles we faced, which is why we are so happy to see our small island finally be accepted with its own Kiribati Language Week. It is wonderful to see how our Kiribati communities have grown across Aotearoa.

In June I was humbled to receive a Queen’s Birthday award, the Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to the Kiribati community and culture. I felt unworthy of this honour, but then I spoke to those that had put in the nomination, who shared their pride for the work I had done and was doing, which was so truly overwhelming, because I think of all those that have worked for our community that have passed on, and all those that contributed in the past – it’s never-ending and we are not done yet!

I said, with the Queen's Birthday honour, it was never, ever in my mind to be rewarded for what I do because I do it with my heart, and I do it because I want it done for my family and my community.

Those of us that came in the 70s worked really hard to be recognised, especially as the ‘smaller’ islands.

Our heritage art and our language capture who we are, and armed with our te rabakau we continue to make and build our expertise and practice to ensure it can be carried and shared for generations to come. Let us be recognised as strong Kiribati people who know where we come from, and this will make us strong individuals who respect each and every culture that we now mingle and associate with.

I love the magic that happens when you work and create. The idea is to know where all the skills have come from – our ancestors, who created the most intricate of objects to live and sing and dance and create the magic that is all part of our lives. Let us recreate them – research them and be part of a drive to recreate these so our future generations can still talk and know about them as our ancestors did. There is magic everywhere and I aspire to inspire before I expire!

There is magic everywhere and I aspire to inspire before I expire!

Making a Te riri ni maie (Kiribati dancing skirt) with harakeke.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy.

Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photo: Valley Profile. Photographer: Kelley Tantau