Relearning How to Breathe: Notes On Being A 'Bad' Survivor

Guest editor of the 呼吸//Breathe essay series, Helen Yeung 希琳 writes on their own experience of survivorship, and how relocating to Guåhan has allowed them to breathe a little easier.

呼吸//Breathe is a series in collaboration with feminist researcher, PhD candidate, community organiser and Migrant Zine Collective founder Helen Yeung 希琳. It aims to capture the multi-faceted, complicated and often contradictory emotions behind survivorship for Asian migrant women and marginalised genders. The Chinese characters 呼 (fu1) 吸 (kap1) mean to exhale and to inhale. When combined, they make up the action of breathing, often unnoticed but vital for our existence and living. The series invites three writers to document emotions such as hope, anger, grief, healing and tenderness, and what it’s like continuing to breathe in the present and every day. 呼吸//Breathe features an editorial by Helen Yeung 希琳, and essays from Dinithi Bowatte, Nalin Samountry and an unnamed Guest Contributor. Each piece is accompanied by artworks from illustrator Liz Yu.

Please note that this series contains sensitive conversations around abuse and harm and may be upsetting for some survivors to read.

Guåhan is an eclectic amalgamation of native flora and fauna, worn-down Wes Anderson-esque pastel buildings, signs with typefaces permanently stuck in the 80s, and hot humid air that lingers on your skin. My partner and I live in a compound surrounded by his family. Outside our blue-and-white house live three pet chickens, our unfinished no-dig garden bed, and a papaya tree we planted a few months ago that is yet to bloom. A colony of cats shares the land with us, usually basking in the sun, or dumpster diving for fiesta leftovers.

I set foot in Guåhan nine months ago, to see if I would want to move here permanently. I'd been desperately wanting to leave Aotearoa after it had become increasingly suffocating and anxiety inducing. The amount of community violence I’d experienced and witnessed had taken a toll on my mental health. When I first arrived on the island, I remember asking a few people what they did each day. The answers varied, but most of them said something along the lines of, We just live. As Māori academic Rangi Matamua says, the reinstating of Indigenous practices in the day to day, such as through the celebration of Matariki, is a vital step towards decolonising our understanding of time. My partner, who is Indigenous to Guåhan, introduced me to this concept after we moved, and reminds me on many occasions to slow down.

With the absence of work, social commitments and competitiveness, and without an overwhelming sense of white toxicity and racism, over time, in Guåhan, I surprisingly learnt to breathe a little easier.

Existence in this new landscape felt simplified: we worked, watered our plants, cooked dinner, took our recyclables to the transfer station, picked up the mail, stocked up on cleaning supplies and groceries, occasionally watched the sunset (rinse and repeat). It sounds a bit mundane, but also perfect, as I finally had the space to learn to better coexist with my trauma.

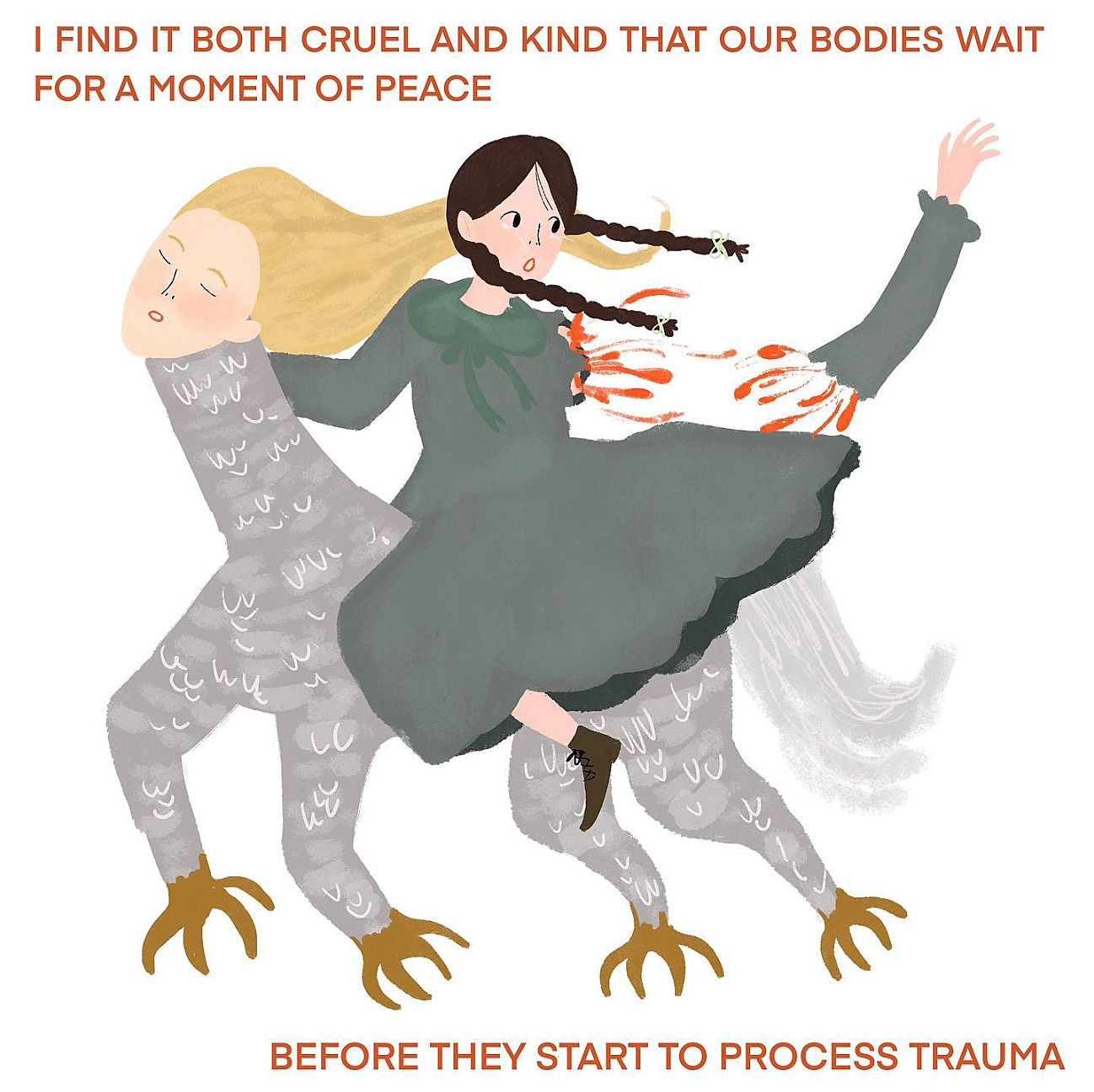

Recently, my online friend and talented artist Isabelle (@icequeeniz) posted an illustration that said, “I find it cruel and kind that our bodies wait for a moment of peace before they start to process the trauma.” I cried, thinking about that in the shower, as it had taken me two years after leaving an abusive relationship to become moderately at ease with my body.

Illustration by Isabelle 柯怡如, sourced from Instagram.

For the past year I’ve had a recurring dream in which I see a woman lying on the side of a highway. She feels the cold night air in her lungs, gasping for breath like a fish out of water as her belly and chest move up and down. There’s a dark viscous liquid flowing out of her abdomen. Her long black hair creeps like blood vessels over the concrete, the blue tips of her translucent fingers grasping for the gravel that surrounds her. She tries to open her mouth, as if she’s whispering cries for help, her lips slightly agape, but the words are inaudible. After the first few times I dreamt of her, I came to the realisation that the woman was me. A visceral depiction of my trauma and grief, helpless, and disconnected from reality.

Although, over the past three years, I’ve shared details of my survivorship online, it was undoubtedly filtered, guarded by a sense of fear in experiencing backlash from people I knew in Aotearoa. After writing down the details of the recurring dream for this series, I didn’t approach the document again for months. I lay awake at night wondering whether the discomfort would be overbearing for others, or would be too intimate to release publicly.

As survivors, we’re often faced with a contradictory pressure, a constant internal conflict of whether we should reveal our trauma histories, down to their most minute details, or whether we should hide these memories forever, so that they don’t disturb others. I’ve gone through both of these experiences.

In my late teens, while I was actively organising in domestic violence prevention, I published an anonymous blog post on a self-proclaimed cis male feminist who was emotionally manipulating and harming women of colour in Tāmaki Makaurau. While I used a pseudonym for his name, needless to say I suffered the consequences of speaking up. I was ostracised by our mutual friends, threatened and gaslighted. Despite being surrounded by a network of activist friends, who would throw around buzzwords like ‘transformative justice’, their failed interventions caused me more harm than good. My 23-year-old self felt defeated, and for the longest time I believed that happy endings were rare for survivors who shared their stories. Deep down, a part of me still believes that.

Several years ago, I left a long-term relationship in which I was experiencing intimate-partner abuse. My sense of self was left shattered, and it became difficult to regulate my emotions, or function day-to-day in wholeness. The days became a blur, and at night I would sleep just to convince myself I’d made it through. The thing about enduring prolonged periods of repeated violence, whether it be emotional, physical or mental, is that the body forces you to continue remembering the inflicted grief, pain and anger after the fact of it happening.

In Cantonese, the characters 呼 (fu1) 吸 (kap1) mean to exhale and to inhale.

In Cantonese, the characters 呼 (fu1) 吸 (kap1) mean to exhale and to inhale. When combined, they make up the action of breathing. It seemed like everyone around me was reminding me to breathe in order to continue living. But the simple task of breathing became a chore. I felt like a live wire, finding triggers everywhere that would cause flashbacks and anxiety attacks. These would be intricately linked to certain words, objects and places I’d associated with past memories. I later found out these were symptoms of post-traumatic stress, and found solace in an online network of women of colour and Queer survivors who were facing the same daily struggles.

The place where I’d existed for my whole life, found my passions, and built my community and network suddenly became claustrophobic. I was prone to suffocation. Which brings me back to my dream. While I could easily tell you this was some romanticised, cryptic or metaphorical depiction of my trauma, the truth is, there’s a reason that I’m on the side of a highway, lost and gasping for air.

A few years ago, Kevin* ran over my foot on the Symonds Street overpass. We were having an argument, and he refused to stop the car to let me leave for work. I took my chance to get out at the traffic lights, but before I closed the door, he drove off, running over my foot. I remember a passerby stopping his bike, and helping me to the footpath. He called an ambulance and stayed by my side. By that time, Kevin had driven back, and was violently yelling at me in front of all the stopped cars. I distinctly remember the man repeatedly saying:

Is he hurting you?

Is he hurting you?

Is he hurting you?

I was in shock, unable to respond as the paramedics drove me to the hospital. In the waiting room, Kevin threatened me not to tell anyone. He leaned in to whisper in my ear:

You deserved it.

That was just one of the many driving-related incidents in our relationship. He would go out of his way to hurt me while driving, braking hard until I was motion sick or to the extent that my collarbone was bruised by the seat belt. He would drive to random locations while cursing at me, then leave me on the side of the road. He told me I was the sole cause of his anger issues, an all-too-common myth told to women by men to avoid accountability for their actions.

Over the course of five years with Kevin, I continued doing the work as a feminist activist, an advocate for survivors, a creator, a writer, a scholar. Like the Guest Contributor describes in her essay, I deeply resonated with the painful irony. As feminist writer and scholar Sara Ahmed puts in her book Living a Feminist Life, “You sense an injustice. You might not have used that word for it; you might not have the words for it; you might not be able to put your finger on it … Things don’t seem right.” Perhaps it was so painfully ironic that I’d convinced myself I was fine, and I let other people do so, too, even after I found the courage to leave.

I support you

Believe survivors

Sorry you went through that :(

Here for you x

Dozens of private messages popped up on my phone screen after I’d spoken up on post-traumatic stress, and why I’d left the relationship. Some of these were from a group of well-known Asian creatives and activists in Tāmaki Makaurau, who offered sympathy or stated that they would minimise contact with Kevin because they cared. After a flurry of messages, my phone went silent for months.

What did surface over social media were photos of these people eating, video-calling, sharing memes, and going on road trips with Kevin, despite knowing of his abusive history. My skin crawled as I witnessed him getting introduced to the women of colour around me. Over time, I lost the gigs I needed to continue to survive as a creative. I stopped getting collaboration opportunities with anyone this network was associated with, but more importantly, I lost the people I thought were part of my chosen pan-Asian family. It felt like my peers, who preached and championed social justice, community wellbeing and inclusivity on TV and in interviews, had suddenly turned a blind eye. I was told this was a personal issue that I needed to handle by myself. All the best for your healing journey [insert prayer hand emoji], they said. In other words: Deal with it.

In retrospect, this was an all-too-familiar replica of the way harm and abuse are handled within the misogynistic, patriarchal structures of Asian migrant families. I’d gone and broken the silence. I’d escaped the comforts of romanticised diasporic art installations, the light-hearted Subtle Asian Trait memes, the dumpling making, and auntie and uncle jokes. The abused woman is shameful, dirty, trouble making, a threat to her family and community. She screams into an echo chamber, pleading for help. As Dinithi expresses in her essay, everybody knows, but no one is listening.

The abused woman is shameful, dirty, trouble making, a threat to her family and community.

As Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha talks about in her book Care Work, the good survivor has no signs of survivorhood: she has no flashbacks, trauma, chronic pain or triggers. She is not crazy, struggling with PTSD, nor would she jump when touched the wrong way. The abuse would miraculously disappear, and she would be as good as new, as if she had never been abused.

After feeling acutely shamed by my community, I was convinced I needed to be a good survivor to be loved again, and after failing repeatedly, I gave up and left Aotearoa, unsure what I would find.

Last month, I entered a new phase of my life, giving birth to my daughter Såhi. The word ‘såhi’ in CHamoru means a new moon rising, or the waxing of the moon – when a non-existent new moon rises and illuminates to a crescent, then transforms over time into a full moon. For me, this was symbolic in many ways; her existence, along with my partner, my new friends and family, and Guåhan, had somehow given me a second chance at life.

For the first time, I understood new ways to be loved and cared for. It was a friend dropping off Tiger Balm for my swollen joints, another friend taking me to browse the aisles of an Asian supermarket so I could feel more at home. It was Nåna deseeding and cutting up a kandot (winter melon) for our chicken soup. It was my partner driving me to watch the sunset while I was in tears, and him saying, “I’m so glad you’re here, and I can share this with you.”

Although this editorial may indicate some sort of resolution and release, I found myself sitting by my laptop after a morning coffee, unable to find an ending. I have a check-up with my midwife today, and I’m planning to chat with her about my postpartum mental health. So perhaps that is my conclusion: as the essays in this series indicate, survivorship is ever changing, messy, and an endless process. Like Nalin, who unpacks intergenerational trauma in her essay, we can still be feeling, learning, healing and ‘not over it’ in our 30s, 40s, 60s and beyond. We’re constantly finding different ways to breathe, to reinvent ourselves, and to fathom new ways to coexist with our trauma.

We’re constantly finding different ways to breathe, to reinvent ourselves, and to fathom new ways to coexist with our trauma.

I’ve come to the conclusion that I am a bad survivor, and I’m fucking proud of it. This series is dedicated to all survivors, but particularly the Asian migrant women and Queer survivors around me who have been silenced, guilted, ostracised and shamed. I hope it provides you with the strength to go on, because I am here, I am on your side.

*This person's name has been changed.

Illustration by Liz Yu.

*

This essay series has received funding support by the Mātātuhi Foundation. Ngā mihi nui!

Struggling with the contents in this article?

The following websites / helplines are available for people in Aotearoa needing support:

- Safe to Talk (sexual harm): 0800 044334, text: 4334, email: [email protected]

- TOAH-NNEST: +64 4 385 9176

- Women's Refuge: 0800 733 843

- Shine domestic abuse services free call: 0508 744 633 (24/7, Live Webchat is also available)

- Family violence information line to find out about local services or how to help someone else: 0800 456 450

- Need to talk? Free call or text: 1737 for mental health support from a trained counsellor

- Youthline: 0800 376 633, free text: 234, email: [email protected]

- Shakti Youth: for migrant and refugee women - 0800 742 584 - 24 hours

- Hohou te rongo kahukura - outing violence: building rainbow communities free from violence

- You, me, us: promoting healthy queer, trans and takatapui relationships

The header images for all essays in this series are by Liz Yu.