Grandpa Lafaiki, Remember With Me

Through the remembrance of her grandfather, Cora-Allan crafts a hiapo, the traditional art of Niuean barkcloth, for the opening of the exhibition Moana Legacy at Tautai Gallery in Auckland.

Moana Legacy was the opening exhibition at the new Tautai Gallery in Auckland. Curated by myself, Moana Legacy features the work of Ahsin Ahsin, Cora-Allan Wickliffe and Kelly Lafaiki, Gina Ropiha, Israel Randell, Mereani Qalovakawasa, Naawie Tutugoro, Rangituhia Hollis and Talia Smith. With the walls painted the colour ‘Goddess’ and the show partway installed, the nationwide lockdown was announced. We dropped what we were doing, and prepared our families to move into Level 4.

I had chosen to open Moana Legacy with a performance around my own work, that of hiapo (Niuean barkcloth). My grandparents were the ones who encouraged me to learn hiapo. The first time my grandfather Vakaafi Lafaiki saw me beat out some cloth using my tools was the day before he passed away. I thought I had plenty of time to make pieces at their house and to have him watch me in the garden while he drank a Lion Red and listened to his island tunes on his portable radio.

I wondered what my grandfather would have thought, as my sister Kelly Lafaiki and I prepared for the exhibition. What we crafted was not what you see on the walls of the gallery today. The extra time during lockdown gave me a sense of freedom, and something else was born. I began creating a new piece of hiapo and suddenly there was a different sense of responsibility with this particular piece. Maybe it was how lockdown was making me feel. Maybe I was anxiously making each day to keep myself calm. Either way, it felt like this piece would have a different ending than all the other hiapo I had created.

After spending days preparing the bark for beating, I thought about the time I spent creating the cloth from beginning to end and how lucky I was to have my sons watching. Sometimes they even participated in the making process. We were in isolation, so spent our days under the trees preparing the cloth, in between the feeding of a new addition to our family, Wakiya-Wacipi, only three months old at the time. On cloudless days, the cloth was stretched out, held down with rocks, to dry.

lockdown was the first anniversary of our grandfather's passing

The day I knew I wanted to shake things up and create an unforgettable moment with this hiapo was when I began pasting the beaten pieces together with glue made from tapioca starch. Midway through lockdown was the first anniversary of our grandfather's passing, and as I was making this cloth, I kept thinking about why I even started to make hiapo.

I continued making the cloth while also having hard conversations with my partner Daniel about whether I should go through with the performance or not. He watched my entire process and rubbed my sore shoulders at the end of each day of beating cloth. Tapa cloth is a well-known Pacific art form and so I understood that the community watching my performance would get how valuable the cloth is. I also knew the reaction might be strong. Through the generations, hiapo live a life of being admired for their patterns and beauty, and my performance would transform the surface of this one.

The last week of lockdown, I stood outside under a pōhutukawa tree and painted the hiapo, as my four-year-old ate snacks and watched Netflix on the mat next to me. As my hands moved with the patterns, I imagined them disappearing before my eyes. The next day we hung it on our living room wall and I decided I couldn’t do it, I wouldn’t be able to paint over this beautiful piece of hiapo.

*

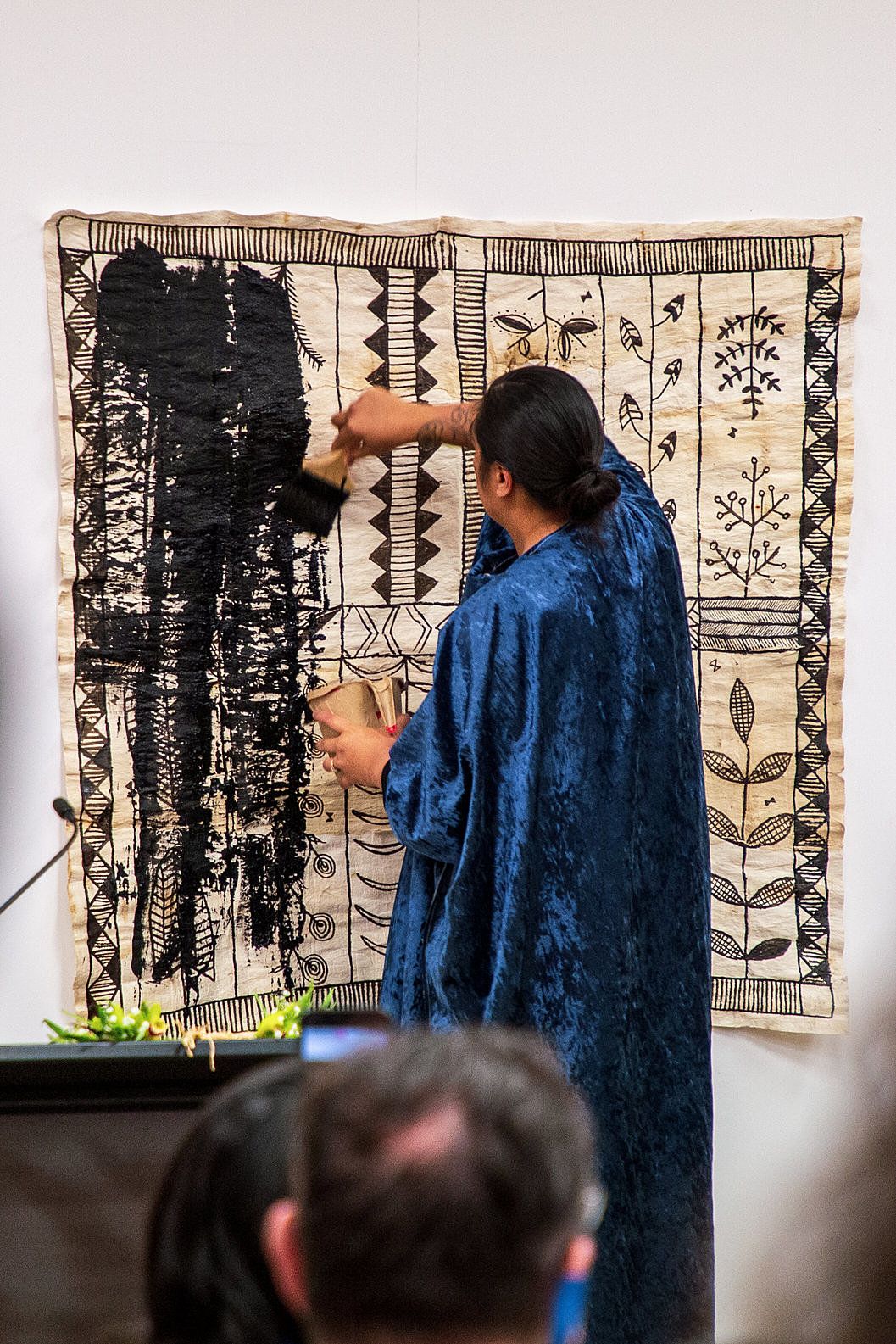

Here I was, after months of planning, standing at the podium and completing my speech as curator for this exhibition. I thanked the artists and took off my earrings and kahoa (lei) as I prepared to start the performance. I took a step towards a makeshift beer-crate shelf that held all of my tools, and pulled a gown made of crushed blue velvet over my body.

I am steady as a rock and sure the audience is with me. That they feel my feelings of loss, mourning, celebration. As I climb the small step-ladder, I ask them one last time, “Remember with me.” I dip my large brush into the ink. I think the audience understands what is about to happen.

Cora-Allan Wickliffe activating her artwork Last Supper with You Revised (2020) at Tautai Gallery Opening, 2020. Photo by Isoa Kavakimotu

Cora-Allan Wickliffe activating her artwork Last Supper with You Revised (2020) at Tautai Gallery Opening, 2020. Photo by Isoa Kavakimotu

Last Supper with You Revised (2020). Moana Legacy (install view) at Tautai Gallery, 2020. Photo by Isoa Kavakimotu

At that moment, I felt the weight of my grandfather on my shoulder and remembered him passing on to me his love for the knowledge of patterns. I then passed this knowledge of cloth onto the shoulders and hearts of everyone who was standing in the room. The brush hit the cloth and I was moved by the gasp of the collective. My shoulders released a tension I didn’t know was there, my heart no longer in my mouth.

I am strangely getting used to painting large strokes over what has taken me nearly two months to complete and, through this, I feel a sense of freedom and the disbelief of eyes and mouths still open. In a space where tapa is sacred and passed down through generations, it feels as though I have somehow broken that cycle. Pushed it into a new path. A path that asks the audience to think not of the object but of the transaction that has occurred between us. I am asking them to remember, and this creates an intense emotion between myself and the audience.

I exited the room to get my earrings and kahoa, bumping into a man gazing up at the hiapo. “Oh my god,” he said, “Why would they do that?” I had no idea how to reply except with, “I did that, I wanted people to remember it.” I left him standing there confused, while I myself was still trying to catch up to what had just happened.

After the performance, some shared with me how it reminded them of their own grandparents. This interaction and moment shared between us opened up thoughts of loss, whether during lockdown or just in our own lives. As a community, it was a moment not only to mark the opening of Tautai Gallery but to explore the art form of hiapo in a way that might invite others to explore its history and journey.

This performance asked those who watched to speak and share what they saw and what my grandfather brought out in me. I know he would have wanted the patterns and story of hiapo to be alive, in the present tense and ready for the next generation. He comes to mind again as I reflect on my drive not just to create, but to maintain and pass down the knowledge that, in his own way, he shared with me.

This performance was part of that continuum. I hope that those who attended the opening of Moana Legacy now feel some of the responsibility I did as I beat out the cloth with my tools, my grandfather Vakaafi Lafaiki sitting in his worn armchair and listening to the island tunes on his radio.

Moana Legacy

Curated by Cora-Allan Wickliffe

6 Jul – 18 Sep 2020

Feature image: Cora-Allan Wickliffe mid-performance at Tautai Gallery Opening, 2020. Photo by Isoa Kavakimotu.