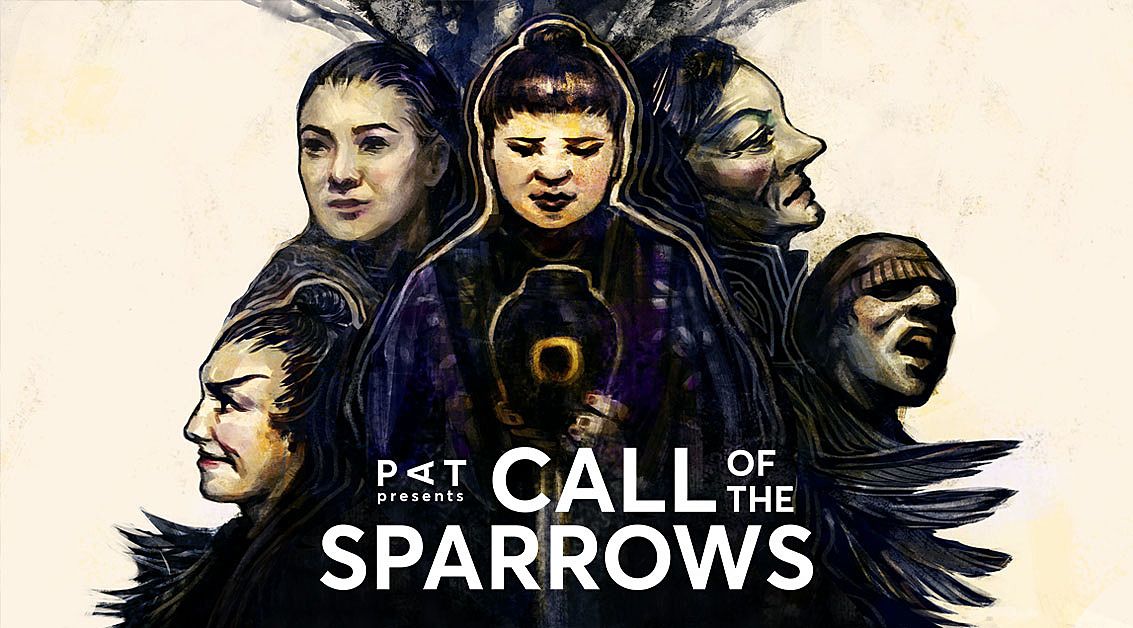

Review: Call of the Sparrows

Call of the Sparrows has all the hallmarks of a debut full-length play, with all the strengths and flaws implied by that label, writes Sam Brooks.

Call of the Sparrows has all the hallmarks of a debut full-length play, with all the strengths and flaws implied by that label, writes Sam Brooks.

In a previous life, Proudly Asian Theatre’s Call of the Sparrows was an award-winning short play, taking home Best Independent Theatre Company and Best Director. Two years on and it’s evolved into a two-act play, running nearly two hours with a cast of five and a week-long season in the Herald Theatre.

The story follows Little Sparrow’s (Amanda Grace Leo) sudden arrival to an isolated village, where she’s been recently betrothed to a man she hasn’t met, the oldest son of the wealthiest family in this community. The Kwan family’s importance is stressed, and she is quickly reduced to being a servant to the matriarch Joa Joa (Alice Canton). The first half of the play follows Little Sparrow’s struggle to maintain her strength and personality against the adversity and exclusiveness of this new community, while the second half follows the aftermath of a life-changing decision that Little Sparrow makes on the behalf of the village.

Chye-Ling Huang’s script is a stylistic grab-bag. Theatrical devices are applied in ways that weigh the story down, rather than aid the drama. The six person cast play numerous characters, but only a few catch our attention, and even some of those feel superfluous to the plot, including a framing device character who only serves to distance the audience from the story, rather than draw them in. The use of direct address is even less successful, as it tries to implicate and draw the audience into moments that don’t ask for it, almost as if surprising us into engaging with the action onstage, rather than trusting each moment to hold us.

The most notable, and consistent, theatrical device used is mask, with Alice Canton’s Joa Joa in particular being a genuine and stirring creation. The script is explicit in its discussion of the metaphorical masks that people use, and it’s delineation of those characters who are genuine not being in masks while the wicked or cruel are in masks is effective. However, the second act, perhaps intentionally, muddies this delineation, and the use of mask becomes an odd affectation.

Huang’s dialogue also varies in effect. When her characters are talking in arch announcements or allegorical stories, it feels like it lines up with the truth of these characters. It feels authentic to how they talk and think. However, when it comes to two human beings talking to each other, most often expositionally, Huang slips into a more contemporary register that feels out of step with the stylised world she has created. This leaves the cast stuck in the middle for the most part, acting out arch characters with modern dialogue, and the disconnect between cast, script and style drags the production down.

The structure of the play also feels uncomfortably unbalanced. The first half is full of world-building and comic hijinks, and feels stretched out far beyond its purpose. Huang establishes her world, the stakes of Little Sparrow’s dilemma and the intricacies of her community effectively and surprisingly quickly, so by the time we get to the halfway point it feels like it should be the end of the play.

The second half is where Huang reveals the theme, and it shifts the place into another realm tonally, and the first few minutes of this act is genuinely stirring and distressing, implicating the audience in this story of a community torn between tradition and the illusion of newness. However, it settles into the same scattershot approach that mars the first act, and a series of twists feel awkwardly applied to the characters and world that Huang has set up.

There’s an energy and ambition here that’s compelling, but the lack of clarity or purpose holds it back. It takes until the end of the first act to hook us into the story, and well into the second act before the import of all that we’ve seen settles in. The use of mask, clowning and physical theatre feels like a distraction from a plot that already requires a lot of explanation and world-building, and instead of focusing on the story being told, we’re switching between ways of understanding these characters and this world, and it leaves the play feeling remote. Even though the play is dealing with vital and important issues, the form feels dated and tired. It’s something you watch, rather than engage with.

James Roque, in his full-length directing debut, goes a long way to uniting the disparate elements in the script, creating some truly beautiful and stirring images and transitioning between scenes elegantly. Micheal McCabe’s costumes locate us cleanly somewhere between the there/then and the here/now, and marks Little Sparrow as something otherworldly without ever overstating it. Christine Urquhart’s set is less successful; it doesn’t feel linked to the text in a substantial way, and it hangs in an awkward place between painterly and utilitarian.

Call of the Sparrows is a fascinating mishmash of style, form and content that never coheres into a compelling piece of theatre. For every moment the play reaches for import, there are many where that import is undercut by a loose structure, tonal inconsistencies and a lack of commitment to the many, many styles it is dipping into to tell this story. The play is at its most potent and clear when it engages with ideas of a community sacrificing history for a chance of a new life, a better life, and even more so with the idea that the new life might not be any better or that much different from the old life.

Unfortunately, this clarity is covered and distorted by the play’s commitments to a style, to a form, and even to a story that doesn’t convey the vitality or importance of this theme. There’s no doubt that Proudly Asian Theatre has clarity and vision behind who they are speaking for and who they are speaking to, it’s a company that wants to tell contemporary Asian stories, but Call of the Sparrows as a piece of work lacks that same clarity.

Call of the Sparrows runs at

the Herald Theatre

from Wednesday 12 October to Sunday 16 October

For tickets to and more information about Call of the Sparrows, go here.