Handshaking with Emotion: A Review of Handshake 3: Reflect

What does a show of contemporary jewellery look like? Lucy Jackson considers the latest exhibition at The Dowse.

What does a show of contemporary jewellery look like? Lucy Jackson considers the latest exhibition at The Dowse.

I wear four rings, my favourite formerly belonged to my mother. One day I tried it on and it was the perfect fit. I have had it on long term loan to me ever since. Aesthetically understated but sentimental – like so much jewellery that is passed down through generations – this simple gold band has no detail, no gem, no inscription.

Mum bought the ring in an antiques store in Hamilton in 1987 and wore it for nearly 30 years before I started wearing it. When my mother found it, she noticed it was a wedding band and thought that the previous wearer must have died or been divorced. The ring’s possible previous life convinced my mum it needed a new home. In this way, jewellery causes you to reflect, whether that be about a story, a time, or yourself. This reflective nature underpins the exhibition Handshake 3: Reflect currently showing at The Dowse.

Handshake 3: Reflect is an exhibition of collaboration with 12 artworks by 12 women artists. The Handshake project (of which there have already been two iterations – Handshake 1 and Handshake 2) provides emerging practitioners mentoring by established international contemporary jewellers, in order to develop their practice and create new work. Handshake connects established with emerging, historical with contemporary, and precious with ordinary.

Contrary to what I was expecting, Handshake 3: Reflect does not show contemporary jewellery which is wearable, instead, it presents artwork that conveys complex and cohesive ideas that contemporary jewellery inspired.

Jewellery can be, and has been used as symbols of identity, status, memory, belonging, and grief. Its very nature is never devoid of meaning or emotionalism. Handshake 3: Reflect counteracts, works with, and challenges these symbols, by creating artwork that pushes the boundaries of contemporary jewellery into somewhere else. Contrary to what I was expecting, Handshake 3: Reflect does not show contemporary jewellery which is wearable, instead, it presents artwork that conveys complex and cohesive ideas that contemporary jewellery inspired.

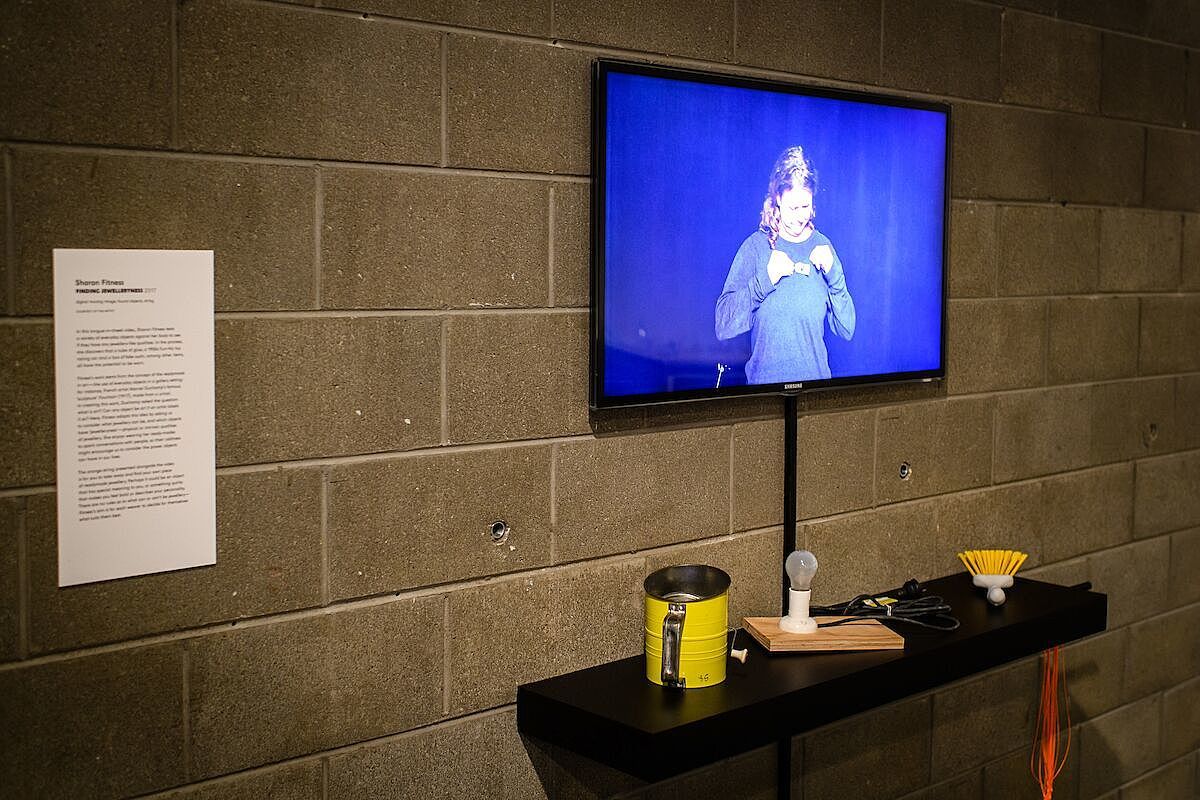

The first artwork I encountered was Sharon Fitness’ Finding Jewelleryness. A video above a bench of objects, (the artist’s ready-mades), the artist questions what can and cannot be jewellery. Fitness goes through a number of objects, trying to place them on her body as an item of jewellery before deciding whether or not they can indeed be considered adornment. The result is almost humorous as Fitness undergoes this ritual, and sets the scene for the exhibition – are we as visitors here to consider what is, and what is not, considered jewellery? Here, Fitness reflects both on art history, (Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades), and the power of everyday objects. At the end of the bench, visitors are welcomed to take piece of string, to combine with one of our own ready-mades and make, or not make, them into jewellery.

In the centre of the room, a checker board-like table of green, blue, grey and pink squares, overlaid with rocks. Raewyn Walsh’s The Rock Garden, is a collection of natural and artificial rocks. The artificial rocks are lighter, hollow and painted in order to be pinned to clothes as brooches, and will not damage our clothing like regular boulders would. Rocks have been chosen to show a relationship with history, as they continue to exist as the world changes around them. Through The Rock Garden Walsh encourages a reexamination, or self-awareness of our relationship to the environments we occupy and how we go about understanding the natural world. Finally, the checker board-like pattern suggests the orderly versus the organic and the games we play with our natural environment in the 21st century.

Across the room are Becky Bliss’ Paradoxical Pegs. A common item of household chores, the peg has seen over 250 years of use. Here, Bliss uses pegs as a symbol of capitalism in domestic life in the 21st century. Although we have faster ways to wash things than 250 years ago, the amount we own is larger and therefore the mundane household chore still takes as long as it did. We are also further ahead in terms of gender equality than we were in the 1760’s, yet domestic chores are still largely, and sadly, maintained by women. Paradoxical Pegs display that regardless of this change, some activities stay the same, like hanging out the washing. Bliss’ artwork contains three clothes lines of pegs, some unusable, and then three large concrete pegs with rope strings below them. These useless pegs show that an object usually seen for its functionality is also a symbol. Perhaps the concrete pegs underneath allude to being weighed down by the large amounts of chores we do to maintain everyday household standards, or the weight of gender stereotypes in modern life? Bliss evokes a reflection upon our own standards and our approaches to a consumerist culture, domestic history and gender roles.

Amelia Pascoe’s Opticks highlights the artist’s personal reflection upon her own practice and career. Pascoe’s previous occupation as a scientist can be seen in her new work as a contemporary jeweller. The blown glass ornaments resemble varieties of a volumetric flask – a common laboratory tool. In Opticks, Pascoe pushes scientific rigidity into random, organic shapes. This results in objects that replicate organs of the human anatomy with likenesses to a heart, intestines and a pancreas. Pascoe reflects on her own science training, where order and logic are prioritised over accidents and curiosities, pushing science into art and art into science. Finally, these glass objects twist and turn, moving with fluidity, which could be a visual metaphor for the artist’s own progress and progression from one career into the next.

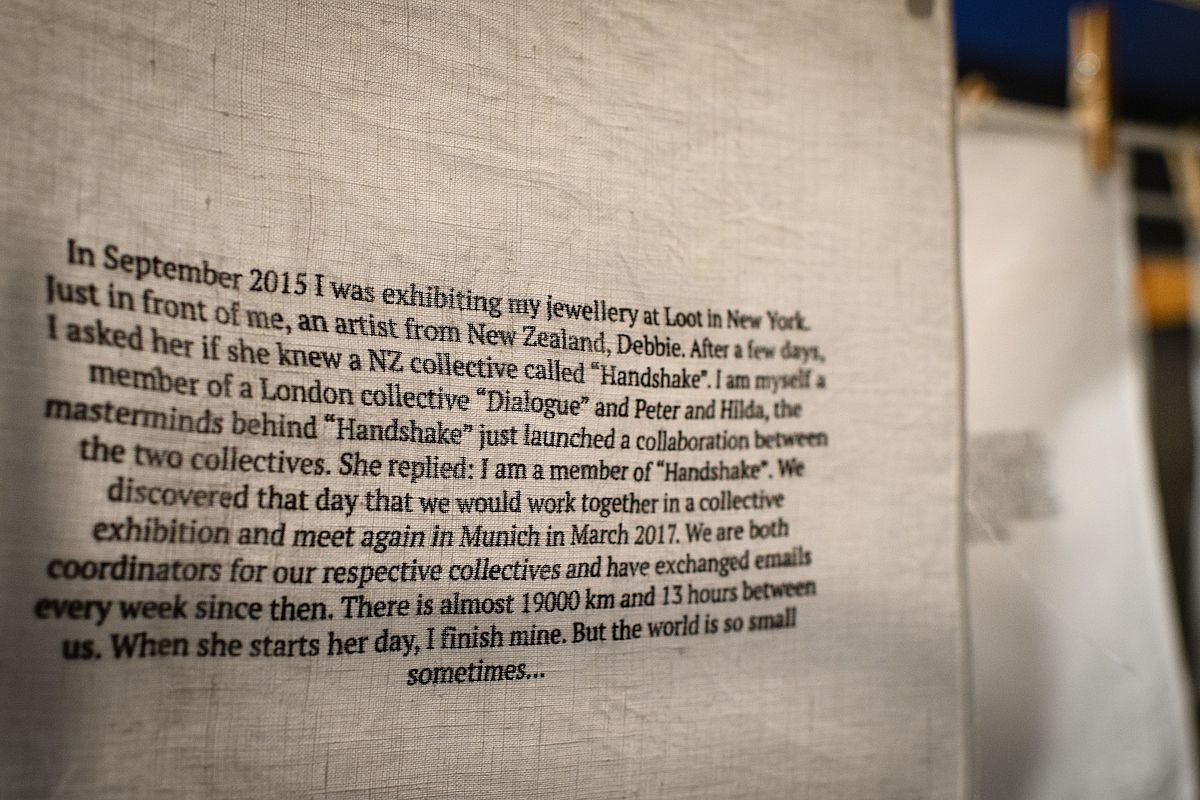

Moving to memory, Debbie Adamson’s Up Close and Far Away, uses handkerchiefs to display memories. To undertake this, the artist made a website and and via social media requested for strangers to submit a memory. Exchanging jewellery for memories, Adamson gave submitters a cast silver teardrop pendant as a trade. These memories were then printed in ink onto cotton and linen handkerchiefs and hung in the gallery space. Throughout the exhibition the hankies will be washed and then rehung. The result will be the ink fading to replicate how memories fade and change over time. Adamson’s project affects more than the visitors in the gallery, the people who submitted memories now have a piece of jewellery from Adamson which could now be the trigger of the memory submitted to the artist, as well as adding on to the memory.

Kathryn Yeats’, Loss Ritual, is what it suggests. For this piece, the artist draws on her own experience of a miscarriage, something that is seldom recognised in the public sphere. On a shelf lay objects that represent the relationship of a baby and mother before it is born. Yeats’ artwork highlights the process of creating to contemplate loss. In front of her installation are two seats, a table with a screen, and some materials – wool and ribbon. The artist asks visitors to sit and follow the instructions on the screen to make a knitted wreath. In the time you spend making, you can, as the artist did with her artwork, think of someone who has passed while you produce something new. This space is one of quiet reflection, and makes the gallery an area where you can grieve with others.

The interactivity, with both Fitness and Yeats’ work encouraged visitor participation in an interesting and new way. Instead of a craft table for children in the corner to make macaroni necklaces, the artists were not only thinking about the production of their work, but how to transfer the physical and emotional elements of creating to the visitors experience. The act of making a wreath, or creating a ready-made necklace is translatable to both visitors who are five or 50 years old, producing a meaningful, rather than obligatory activity in the gallery.

Jewellery has the ability to transport us through history, time, memory, grief, status and identity.

There is not enough space to allow a detailed analysis of all twelve artworks in Handshake 3: Reflect. Each artwork is rich with concept and execution, and what would be more helpful in understanding is standing in front of these pieces, extrapolating your own meanings, stories and connections.

Many objects in our lives make us think beyond the aesthetic and into something non-visible. However, jewellery has the ability to transport us through history, time, memory, grief, status and identity. The Handshake artists do more than make us reflect on the nature and future of contemporary jewellery, they also make us reflect on ourselves, our relationships, our stories, our connections, and consider whether a gold band on a finger is only just that, or whether it is much, much more.

Some of the ideas running throughout Handshake 3: Reflect, have been witnessed by this ring I wear on my finger; through 30 years with my Mother, and now with myself. The ring will be worn through different circumstances and emotions. Perhaps I might have a daughter or son who looks at the ring and thinks of their Mother, their Grandmother, and ponders what the antique shop looked like in 1987. Handshake 3: Reflect allows me to contemplate these different stages and situations we go through as humans and how these concepts are not limited to, but interconnected with jewellery.

Handshake 3: Reflect

The Dowse Art Museum

5 August 2017 – 3 December 2017

All images courtesy of the artists and The Dowse Art Museum.