In-between Years: A Review of ‘A Serious Girl’

Jessica Douglas considers Roberta Thornley's latest exhibtion and shifting from adolescence to adulthood.

Jessica Douglas considers Roberta Thornley's latest exhibtion and shifting from adolescence to adulthood.

Although I was never a sporty teenager, over the past few years I’ve become increasingly dependent on exercise for its meditative qualities. Whether it’s running, swimming, kickboxing or a class at the gym, I lose all sense of time. When I focus on breathing, on pacing myself and on controlling my body, my thoughts, pressures, stresses and fears mellow, and suddenly I am ready to take on any challenge.

This sense of power, struggle and motivation through sport is something that Roberta Thornley recognises, and captures through dark and cinematic photography. Her exhibition A Serious Girl, at Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, is a celebration of this gruelling glory. She sees the splendour in that ability to transform and train your body into accomplishing magnificent feats.

This isn’t just the physical kind of beauty that comes with a creamy complexioned teenager, whose future is bright and best years are still to come, but beauty in the vulnerability they possess.

The title draws a parallel between Thornley’s subject choice and her current home of Whanganui. The serious girl is Millie, an 18-year-old Whanganui gymnast who’s heading to Denmark in September on a scholarship for gymnastics training. Thornley borrowed the exhibition title from a painting by Whanganui painter Edith Collier of the same name, A Serious Girl. Millie’s story is similar to Collier’s (1885-1964), who travelled to London in her twenties to study art and begin a new phase in her life.

Although Thornley has never seen that particular work (in fact it still remains a mystery after much research from her and those at the Sarjeant), she stumbled across the title in a book, and it immediately resonated with her and henceforth became a springboard for what is now this show. Thornley’s first encounter with Collier was with, The Pouting Girl (1920). In this watercolour, a young girl looks off to her right in defiance, her lower lip pulled in. Millie is perhaps an amalgamation of these two concepts – a young woman who is serious and venerable and knows where she wants life to take her.

Though Millie and Collier are Whanganui locals, Thornley is originally from Auckland, where she grew up and studied at University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts. Upon arriving in Whanganui in 2015 for her five-month residency at Sarjeant Gallery’s Tylee Cottage, Thornley immediately felt a connection to the town and to its photographic history and legacy, and she has since called it home. In fact it was this intrigue that drove her to apply for the residency in the first place. Frank Denton, Andrew Ross and Laurence Aberhart are just a few of the photographers associated with Whanganui, and Ans Westra, Ben Cauchi and Richard Orjis are among those who have been awarded the residency. In a recent phone conversation she comments, “The conversation about photography is a really interesting one. You experience it in the likes of Robin Morrison, where he shot in the same places as [Laurence] Aberhart but in a completely different way”.

When applying for this residency, Thornley knew she wanted to work with teenagers – they bring a certain kind of energy that she likes to work with. There’s also a haunting beauty in their in-between years, “shifting from adolescence to adulthood” as Dr Kriselle Baker describes it in her essay published to coincide with Thornley’s 2012 exhibition at Tim Melville Gallery, I Will Meet You There. This isn’t just the physical kind of beauty that comes with a creamy complexioned teenager, whose future is bright and best years are still to come, but beauty in the vulnerability they possess. Thornley comments, “I see vulnerability as strength. I don’t know what it is that draws me to my subjects, but the more I do this the more I get an idea of their type of character. I get a strong sense of Millie being an authentic individual, an old soul. It came across really early on with her, I just got this feeling…”

Thornley’s intuition was right. During their time together, their bond grew stronger and they now consider one another close friends. Just recently, Thornley attended Millie’s fundraising event, titled ‘Not Such a Serious Girl’, at the local theatre. Like a proud mother, she lovingly sent me the video of Millie’s routine. So, even though one may question the ethics to this – photographing women as young and sensitive as Millie – it’s clear that their relationship is trusting and genuine. Millie may be vulnerable, but she’s clearly comfortable in Thornley’s company – comfortable enough to let this sensitivity come through.

Thornley of course isn’t the only artist to capture that hinterland between teenage years and adult life. Rineike Dikstra (b. 1959), a Dutch photographer, is perhaps best known for her Beach Portraits (1992-98), where she photographed adolescent bathers in different locations across Europe and the United States. Like Thornley, Dijkstra captures young adults in their transitional phase and uses soft and hazy backdrops, with the sun setting over moody clouds.

Thornley has photographed teenagers since she herself was one, casually shooting siblings, friends and her friends’ siblings in high school. Upon reflection, she says her relationship to teenagers and to this time has changed since growing older. It has become more nostalgic.

Aware that she wanted to work with teenagers but not knowing any in Whanganui, Thornley held an open casting session one weekend in June 2015. When describing this experience, she says, “It was a complete disaster. It was so awkward. They were all so great but it made me realise how much it matters who I’m working with. It needs to feel authentic for me and the story I’m trying to create.” Millie had sent Thornley an email saying how she was interested in the project but couldn’t make it to the casting session as she had a gymnastics competition that weekend. Thornley suggested another time one afternoon where she and Millie could meet at one of her training sessions. This get-together proved a lot more organic for Thornley, seeing Millie in her natural environment and taking their relationship from there.

Thornley herself understands Millie’s intense drive to push her body. As a teenager and during her years studying at Elam, Thornley trained and played across numerous hockey teams. This led me to wonder whether or not A Serious Girl was somewhat autobiographical. To help explain, Thornley sent me an article the author Tessa Duder wrote about her quartet of Alex novels (1987-91). As a former swimmer, Duder describes her connection to Alex, a champion swimmer training for the Olympics, as authentic but not necessarily drawn from real life. Duder writes, “That authenticity took time and effort, reaching back into forgotten memories, digging out old scrapbooks and contemporary accounts… But authenticity doesn’t mean ‘semi-autobiographical’.”

Thornley has always been interested in gymnastics, though only as a casual spectator. She kept a scrapbook of gymnastic cut-outs as a child and she still finds herself watching it when the Olympics roll around. It’s more the theatrics and impossibility of it that she’s interested in, rather than the sport itself. She describes it as being very much about body and mind – an individual sport that is much more challenging psychologically than team sports, like hockey.

Writing about her own sport experience, in 2011 Thornley said “With each new training session came the hope and anticipation of doing something new, of stretching myself that much further… these were the moments when, as an athlete, I learnt the most about myself; when the barnacles of our existence were showing on my flesh and in the air and on my clothes.”

By ‘barnacles of existence’, she is referring to those tell-tale signs that suggest we’re alive. The condensation that appears when exhaling hot breath into a cold morning’s training session. The burning in your lungs and pain in your thighs and calf muscles when relentlessly pushing your body. The tangy sweat that lingers and salty residue it brings across your skin.

The tangy sweat that lingers and salty residue it brings across your skin.

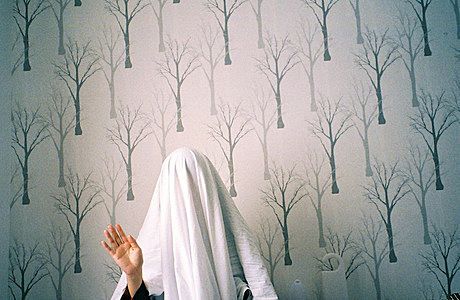

Alongside these intense moments that come with extreme training are the times when an athlete must rest, recover and stretch, particularly in the case of injuries. Originally, Thornley had envisioned photographing Millie in fluid, gymnastic stances, however Millie sustained an injury only a couple of weeks into their time together, immediately changing the scope of the project. Instead of depicting Millie mid-pose, we get to experience her in a natural and domestic setting at her Castlecliff Beach home in Whanganui. Thornley recognises the importance of domestic spaces for a competitive sportsperson and teenager – when arriving home from a game or competition, it is the first place one would replay movements and strategise for the next championship.

Thornley says, “In this case it was very much about… using her environment as the stage for things to play out”. As a result, there’s more of a narrative to these photographs than Thornley’s past works, which are mostly set in constructed spaces.

Across these works, we’re invited into Millie’s family lounge as in Lowtide, Lounge (Waiting for the Flood) and Oceanview. There’s a sense of melancholy that lingers here, Thornley brings out the space’s serenity and eerie quietness. This silence is where the works hold their strongest power. They don’t shout or scream, demanding attention, but ominously sit still. They patiently wait for you to turn your head, settle your feet, and take focus.

In Real Art Roadshow: the book (2009), Gerald Barnett uses the term “velvety darkness” to describe the inky blackness in Thornley’s work, which can accurately be applied here, too. This is particularly true for the works Millie and Backyard Dahlias, where you get a strong sense of texture – in the twill of Millie’s leotard and fuzzy softness of the petals, and in the beads of sweat on Millie’s forehead and drops of dew on the flowers.

Connected by their sense of texture, these two works additionally share gentle curving lines and glistening reds. The dahlias can also be taken to represent Millie. Dahlias are beautiful, their soft, multilayered petals adding body and texture to its arrangement. They symbolise the ability to draw from inner strength to succeed, to stay graceful under pressure, to travel, to make a major, positive life change, to stand out from the crowd, and to follow one’s own unique path. This work recalls the haunting still lifes by Anne Noble (another Whanganui photographer) or Fiona Pardington, as with her succulent reds against black in Still Life with My Mother’s Roses, Pomegranates & Plastic Bottles, Ripiro (2013).

Socks is another work freighted in symbolism, a pair of socks suggesting protection or warmth from a difficult situation. Though Millie does not wear socks when competing, rules state that she and other gymnasts must wear them when watching from the arena sidelines. Thornley also draws a connection here to white line fever – a term used to describe the radical change in people’s behaviour when they cross a line during sport and their adrenaline takes over. With slightly worn white socks against a dark background, toe-end facing the right, immediately this photograph evokes Yvonne Todd’s Wet Sock (2005), while also drawing an association to Thornley’s earlier sock work, Match (2008).

Some have drawn a connection between Thornley’s work and films by David Lynch. Both use a dark tinge or tone, resulting in a surreal and trancelike viewing for the audience. I also get a sense of Vincent Ward’s photography in her work, in its cold wetness and cinematic style. There’s a slightly American Psycho vibe too, in that unsettling, eerie feeling which lingers long after you’ve turned your eyes away.

Thornley herself cites a “vast and broad and messy” variety of influences: Paolo Pelligrin, Helmut Newton and Julia Margaret Cameron. American photographers Bruce Weber, Alec Sloth, Annie Leibovitz and Lee Miller. Plus the treatment and drama in Trent Parke’s work, and closer to home, the bold buildings and interior spaces in Andrew Ross’ photography.

Although Thornley draws inspiration from a variety of photographers, her work is unique in its ability to surface a variety of different references and meanings. Within its glowing darkness, every viewer is able to take away his or her own personal response to each work. I look at Millie and think about the endless slapping of my own feet on the pavement when I go for a run, willing my body to keep moving forward.

A Serious Girl

Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui

27 May 2017 – 20 August 2017

Tim Melville Gallery, Auckland

28 August 2017 – 30 September 2017

All photographs courtesy of the galleries and the artist.